Local time (mathematics)

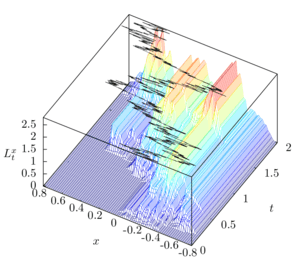

In the mathematical theory of stochastic processes, local time is a stochastic process associated with semimartingale processes such as Brownian motion, that characterizes the amount of time a particle has spent at a given level. Local time appears in various stochastic integration formulas, such as Tanaka's formula, if the integrand is not sufficiently smooth. It is also studied in statistical mechanics in the context of random fields.

Formal definition

For a continuous real-valued semimartingale , the local time of at the point is the stochastic process which is informally defined by

where is the Dirac delta function and is the quadratic variation. It is a notion invented by Paul Lévy. The basic idea is that is an (appropriately rescaled and time-parametrized) measure of how much time has spent at up to time . More rigorously, it may be written as the almost sure limit

which may always be shown to exist. Note that in the special case of Brownian motion (or more generally a real-valued diffusion of the form where is a Brownian motion), the term simply reduces to , which explains why it is called the local time of at . For a discrete state-space process , the local time can be expressed more simply as[1]

Tanaka's formula

Tanaka's formula also provides a definition of local time for an arbitrary continuous semimartingale on [2]

A more general form was proven independently by Meyer[3] and Wang;[4] the formula extends Itô's lemma for twice differentiable functions to a more general class of functions. If is absolutely continuous with derivative which is of bounded variation, then

where is the left derivative.

If is a Brownian motion, then for any the field of local times has a modification which is a.s. Hölder continuous in with exponent , uniformly for bounded and .[5] In general, has a modification that is a.s. continuous in and càdlàg in .

Tanaka's formula provides the explicit Doob–Meyer decomposition for the one-dimensional reflecting Brownian motion, .

Ray–Knight theorems

The field of local times associated to a stochastic process on a space is a well studied topic in the area of random fields. Ray–Knight type theorems relate the field Lt to an associated Gaussian process.

In general Ray–Knight type theorems of the first kind consider the field Lt at a hitting time of the underlying process, whilst theorems of the second kind are in terms of a stopping time at which the field of local times first exceeds a given value.

First Ray–Knight theorem

Let (Bt)t ≥ 0 be a one-dimensional Brownian motion started from B0 = a > 0, and (Wt)t≥0 be a standard two-dimensional Brownian motion W0 = 0 ∈ R2. Define the stopping time at which B first hits the origin, . Ray[6] and Knight[7] (independently) showed that

-

(1)

where (Lt)t ≥ 0 is the field of local times of (Bt)t ≥ 0, and equality is in distribution on C[0, a]. The process |Wx|2 is known as the squared Bessel process.

Second Ray–Knight theorem

Let (Bt)t ≥ 0 be a standard one-dimensional Brownian motion B0 = 0 ∈ R, and let (Lt)t ≥ 0 be the associated field of local times. Let Ta be the first time at which the local time at zero exceeds a > 0

Let (Wt)t ≥ 0 be an independent one-dimensional Brownian motion started from W0 = 0, then[8]

-

(2)

Equivalently, the process (which is a process in the spatial variable ) is equal in distribution to the square of a 0-dimensional Bessel process, and as such is Markovian.

Generalized Ray–Knight theorems

Results of Ray–Knight type for more general stochastic processes have been intensively studied, and analogue statements of both (1) and (2) are known for strongly symmetric Markov processes.

See also

Notes

- Karatzas, Ioannis; Shreve, Steven (1991). Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus. Springer.

- Kallenberg (1997). Foundations of Modern Probability. New York: Springer. pp. 428–449. ISBN 0387949577.

- Meyer, P. A. (2002) [1976]. "Un cours sur les intégrales stochastiques". Séminaire de probabilités 1967–1980. Lect. Notes in Math. 1771. pp. 174–329. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-45530-1_11.

- Wang (1977). "Generalized Itô's formula and additive functionals of Brownian motion". Zeitschrift für Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie und verwandte Gebiete. 41: 153–159. doi:10.1007/bf00538419.

- Kallenberg (1997). Foundations of Modern Probability. New York: Springer. pp. 370. ISBN 0387949577.

- Ray, D. (1963). "Sojourn times of a diffusion process". Illinois Journal of Mathematics. 7 (4): 615–630. MR 0156383. Zbl 0118.13403.

- Knight, F. B. (1963). "Random walks and a sojourn density process of Brownian motion". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 109 (1): 56–86. doi:10.2307/1993647. JSTOR 1993647.

- Marcus; Rosen (2006). Markov Processes, Gaussian Processes and Local Times. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–56. ISBN 0521863007.

References

- K. L. Chung and R. J. Williams, Introduction to Stochastic Integration, 2nd edition, 1990, Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-0-8176-3386-8.

- M. Marcus and J. Rosen, Markov Processes, Gaussian Processes, and Local Times, 1st edition, 2006, Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-86300-1

- P.Mortars and Y.Peres, Brownian Motion, 1st edition, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-76018-8.