Little Butte Creek

Little Butte Creek is a 17-mile-long (27 km) tributary of the Rogue River in the U.S. state of Oregon. Its drainage basin consists of approximately 354 square miles (917 km2) of Jackson County and another 19 square miles (49 km2) of Klamath County. Its two forks, the North Fork and the South Fork, both begin high in the Cascade Range near Mount McLoughlin and Brown Mountain. They both flow generally west until they meet near Lake Creek. The main stem continues west, flowing through the communities of Brownsboro, Eagle Point, and White City, before finally emptying into the Rogue River about 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Eagle Point.

| Little Butte Creek | |

|---|---|

The north fork of Little Butte Creek | |

Location of the mouth of Little Butte Creek in Oregon | |

| Etymology | Named after Snowy Butte (now Mount McLoughlin) |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| Counties | Jackson County, Klamath County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Near Lake Creek |

| • location | Cascade Range, Jackson County, Oregon |

| • coordinates | 42°25′11″N 122°37′08″W[lower-alpha 1] |

| • elevation | 1,647 ft (502 m)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Mouth | Rogue River |

• location | about 3 miles (4.8 km) southwest of Eagle Point, Jackson County, Oregon |

• coordinates | 42°27′03″N 122°52′47″W[2] |

• elevation | 1,204 ft (367 m)[2] |

| Length | 17 mi (27 km)[3] |

| Basin size | 373 sq mi (970 km2)[4][5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | below Eagle Point[lower-alpha 2] |

| • average | 232.3 cu ft/s (6.58 m3/s)[lower-alpha 2] |

| • minimum | 5.8 cu ft/s (0.16 m3/s)(June 6, 1926)[7] |

| • maximum | 10,000 cu ft/s (280 m3/s)(January 7, 1948)[8] |

Little Butte Creek's watershed was originally settled by the Takelma, and possibly the Shasta tribes of Native Americans. In the Rogue River Wars of the 1850s, most of the Native Americans were either killed or forced onto Indian reservations. Early settlers named Little Butte Creek and nearby Big Butte Creek after their proximity to Mount McLoughlin, which was known as Snowy Butte. In the late 19th century, the watershed was primarily used for agriculture and lumber production. The city of Eagle Point was incorporated in 1911, and remains the only incorporated town within the watershed's boundaries.

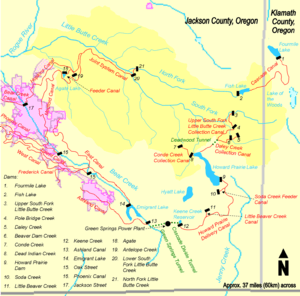

Large amounts of water are diverted from Little Butte Creek for irrigation, water storage, and power generation. Canal systems deliver the water to nearby Howard Prairie Lake and the Klamath River watershed, Agate Lake, and the Rogue Valley.

Despite being moderately polluted, the creek is one of the best salmon-producing tributaries of the Rogue River. Coho and Chinook salmon migrate upstream each year; however, several dams hinder their progress. A fish ladder was built in 2005 to help fish swim past a dam constructed in Eagle Point in the 1880s, but was destroyed by flooding just three months later. It was rebuilt in 2008. Restoration of a 1.3-mile (2.1 km) artificially straightened section of the creek in the Denman Wildlife Area was completed in 2011.

Course

Little Butte Creek begins in the Cascade Range near Mount McLoughlin and Brown Mountain. It flows generally west over approximately 17 miles (27 km) to its confluence with the Rogue River.[4][3] There are two main forks of Little Butte Creek: the North Fork and the South Fork. The South Fork's headwaters are at 5,713 feet (1,741 m) above sea level, while the North Fork's headwaters are considerably lower at 4,638 feet (1,414 m).[lower-alpha 3] They meet each other at 1,647 feet (502.0 m), creating the main stem itself.[lower-alpha 1] Little Butte Creek's mouth is at 1,204 feet (367.0 m) above sea level,[2] giving the creek an overall gradient of approximately 25 feet per mile (4.7 m/km).[4]

The north fork begins at Fish Lake, near Mount McLoughlin. It flows west, collecting only minor tributaries, before merging with the south fork.[9] The south fork's headwaters are just south of the 7,311-foot-tall (2,228 m) Brown Mountain.[4] The Pacific Crest Trail passes through this area.[10] It flows west, receiving Beaver Dam Creek and Dead Indian Creek on the left bank.[9] Beaver Dam Creek drains approximately 28 square miles (73 km2), and Dead Indian Creek has a watershed of about 22 square miles (57 km2).[4] The Dead Indian Soda Springs are on Dead Indian Creek, about a mile south of its confluence with the south fork.[11] The south fork then turns northwest, collecting water from Lost Creek on the left, near the Lost Creek Bridge, built in 1919.[9] Lost Creek drains about 17 square miles (44 km2).[4]

Just after the two forks merge about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Medford,[12] Little Butte Creek receives Lake Creek on the left bank, flowing through the community of the same name at river mile (RM) 17 or river kilometer (RK) 27.[3][9] Lake Creek drains 15 square miles (39 km2).[4] The main stem is crossed by South Fork Little Butte Creek Road in Lake Creek.[3] Water is diverted here into the Joint System Canal for storage in Agate Lake and to provide irrigation for the Medford region.[5] A few miles west, the creek receives Salt Creek and Lick Creek on the right bank, which have watersheds of 17 and 16 square miles (44 and 41 km2), respectively.[4] Oregon Route 140 crosses the creek at RM 10 (RK 16).[13]

The creek turns southwest, flowing through Eagle Point.[4] Four bridges span the stream in Eagle Point: East Main Street, Loto Street, and the Antelope Creek Bridge near RM 5 (RK 8), and Oregon Route 62 at RM 4 (RK 6).[14] Near RM 3 (RK 5), Little Butte Creek receives Antelope Creek on the left. Antelope Creek is its largest tributary, draining 58 square miles (150 km2).[4][5] Agate Lake on Dry Creek is in the Antelope Creek watershed.[4][9] At RM 1.5 (RK 2.4) the creek is crossed by Agate Road.[15] It then flows into the Rogue River 132 miles (212 km) from its mouth at the Pacific Ocean.[16] Little Butte Creek's mouth is in the Denman Wildlife Area, approximately 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Eagle Point, and about a mile southeast of Upper Table Rock.[4][9]

Discharge

The United States Geological Survey monitored the flow of Little Butte Creek at seven different stream gauges: two on the south fork, three on the north fork, and two on the main stem. The first opened in 1908 at the newly constructed Fish Lake Dam on the north fork, while the last opened in 1927 near the Big Elk Ranger Station on the south fork. By 1989, all seven were closed. The data recorded by the lowermost gauges of both forks and the main stem are listed below.

| Stream | Location | Drainage basin | Years recorded | Average flow[lower-alpha 2] | Maximum flow | Minimum flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Fork | near mouth | 52 sq mi (130 km2)[17] | 1922–1931 | 57.0 cu ft/s (1.61 m3/s)[17] | 1,750 cu ft/s (49.55 m3/s) (December 22, 1964)[18] |

0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) (numerous times 1922–1968)[19] |

| South Fork | near mouth | 138 sq mi (357 km2)[20] | 1922–1982 | 97.3 cu ft/s (2.76 m3/s)[20] | 6,280 cu ft/s (177.8 m3/s) (May 25, 1942)[21] |

3.0 cu ft/s (0.085 m3/s) (July–August 1931)[22] |

| Main stem | RM 4 (RK 6.5) | 293 sq mi (759 km2)[6] | 1908–1950 | 232.3 cu ft/s (6.578 m3/s)[6] | 10,000 cu ft/s (280 m3/s) (January 7, 1948)[8] |

5.8 cu ft/s (0.16 m3/s) (June 6, 1926)[7] |

Watershed

Little Butte Creek drains approximately 373 square miles (966 km2) of southern Oregon. Elevations range from 1,204 feet (367.0 m) at the mouth of the creek to 9,495 feet (2,894 m) at the summit of Mount McLoughlin, with an average of 3,496 feet (1,066 m).[4] Forest accounts for about 65 percent of the total area of the watershed, while 32 percent is farmland. The remaining three percent is within the Eagle Point city limits. Forty-eight percent of the watershed is federally owned, 50 percent is privately owned, and Eagle Point accounts for the remaining two percent.[5] Over 10,000 people live within the watershed's boundaries.[4]

The region experiences a Mediterranean climate. Temperatures average from 90 °F (32 °C) in the summer to 20 °F (−6.7 °C) in the winter. The average precipitation in the area ranges from 19 inches (480 mm) in the lower regions to over 50 inches (1,300 mm) in the upper reaches. July through October are the driest months, while December through April are the wettest. Thirty-four percent of the surface runoff in the watershed is collected from rain, 31 percent from rain on snow, and 35 percent from snowmelt.[4]

The two main geologic regions in the Little Butte Creek watershed are the High Cascades and the western Cascades. The western Cascades make up the western two thirds of the watershed, generally below 4,800 feet (1,500 m) in elevation. Steep, rugged canyons are common in this region. The lower stretches of the watershed contain soils such as decomposed lavas, clay, and gravel.[4][23] The High Cascades compose the eastern third of the watershed, including volcanoes such as Brown Mountain and Mount McLoughlin, and lava plateaus. In some places, streams descend over 300 feet per mile (60 m/km). Nearby watersheds include two Rogue River tributaries—Big Butte Creek to the north and Bear Creek to the south—and small Klamath River tributaries to the east.[4]

As of 2003, there were 581 water rights recorded in the watershed, with 394 of them related to irrigation. Four hundred sixty-six water diversions were also recorded. In the summer, many streams are over-appropriated, leading to frequent water shortages along the lower portion of the creek.[4][24]

Flora and fauna

The flora in the Little Butte Creek watershed is predominately temperate coniferous forest, which makes up approximately 65 percent of the total area.[4][25] The lower regions are covered with chaparral, and the upper regions by fir forests. The chaparral region is inhabited by oaks such as garry oak and California black oak, with an understory of buckbrush and manzanita. Coast douglas-fir, sugar pine, ponderosa pine, California incense-cedar, and white fir are the most common trees found in the mixed coniferous forest. Shasta red fir, white fir, and the noble fir grow in the higher elevations of the watershed. Mountain hemlock, lodgepole pine, Sitka mountain-ash, and squashberry also grow in this region.[25] Chinquapin can be found around Fish Lake.[26] The most common species of plants above 6,000 feet (1,800 m) near the tree line on Mount McLoughlin and Brown Mountain include whitebark pine, mountain hemlock, Coast Range subalpine fir, heather, and mountain heather.[25]

Many species of birds have been spotted in the Little Butte Creek region. Twenty-two species are known to breed in the chaparral region, including several species of wrens, blackbirds, and sparrows. The mixed coniferous forest is home to white-headed woodpeckers, pygmy nuthatches, green-tailed towhees, northern pygmy-owls, Vaux's swifts, winter wrens, and MacGillivray's warblers. The American coot has also been spotted in several places along the creek.[27] Williamson's sapsuckers, black-backed woodpeckers, Canada jays, and hermit warblers frequent the higher elevations. The near-threatened olive-sided flycatcher and Cassin's finch also live in this area. Eurasian three-toed woodpeckers and Clark's nutcrackers have been spotted near the tree line.[25] The endangered Townsend's big-eared bat is known to live in the watershed.[28]

Little Butte Creek is known to be one of the best salmon producing tributaries of the Rogue River,[4] and is also one of only a few streams in the Upper Rogue watershed to support salmon populations.[29] The most common anadromous fish inhabiting the creek include chinook and coho salmon, and sea-run cutthroat trout. The Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast Coho Salmon Evolutionary Significant Unit is listed as threatened (2011).[30] Coho salmon are known to spawn in 46 miles (74 km) of streams in the Little Butte Creek watershed.[4][5] An estimated 35,131 Coho salmon lived in the creek in 2002.[5] Resident fish include coastal cutthroat trout, sculpins, rainbow trout, and brook trout.[4][12]

History

The Little Butte Creek area was originally settled by the Takelma,[4] and possibly the Shasta tribe of Native Americans.[31] The first non-indigenous settlers arrived in the Eagle Point region in 1852.[4] Little Butte Creek was named by the early settlers for its close proximity to Mount McLoughlin (also known as Snowy Butte), as was nearby Big Butte Creek.[32] Due to conflicts with the Rogue River Indians, Major J. A. Lupton gathered 35 men from Jacksonville on October 8, 1855, and attacked the Native Americans near the mouth of Little Butte Creek, killing about 30 of them. Lupton was also killed, and eleven of his men were injured.[33] On December 24 of the same year, Captain Miles Alcorn discovered and attacked a Native American camp on the north fork, killing eight.[34] On Christmas, the following day, another band of Native Americans were attacked near Little Butte Creek's mouth; some fled, while the rest were either captured or killed.[35]

By the late 1850s, the land was primarily used for agriculture and lumber in the upper regions.[4] A sawmill was constructed on the north fork in the 1870s.[36] In 1901, the Sunnyside Hotel was built by Alfred Howlett on the banks of the creek in Eagle Point.[37] Eagle Point was later incorporated in 1911, and remains the only incorporated town in the watershed.[4] In 1917, manganese ore was discovered near the confluence of South Fork Little Butte Creek and its tributary, Lost Creek. Mined nodules consisted of approximately 55 percent manganese and weighed up to 50 pounds (23 kg). Cinnabar was also discovered in the area.[38] In 1922, the 58-foot-long (18 m) Antelope Creek Covered Bridge was constructed on Antelope Creek. It was moved to Little Butte Creek in Eagle Point in 1987.[39]

Diversions and dams

Some of the water in the Little Butte Creek watershed is diverted to irrigate the Rogue Valley and to supplement Bear Creek, both roughly 15 miles (24 km) to the southwest.[4] In the late 19th century, a large number of orchards were planted near Ashland. They were initially irrigated by Bear Creek; however, there was not enough water to satisfy the orchards' needs. In 1898, the Fish Lake Water Company was established to solve the problem. The company proposed the enlargement of Fourmile and Fish lakes by impounding Fourmile Creek and North Fork Little Butte Creek, respectively, and connecting them via the Cascade Canal. Construction of the temporary Fish Lake Dam began in 1902. Around this time, construction of the Joint System Canal to the west also began. Construction of Fourmile Lake Dam started in 1906, along with the Cascade Canal. A network of other small canals, such as Hopkins Canal and the Medford Canal, were also built in the Rogue Valley around this time.[40] Fish Lake Dam was completed in 1908, creating the 7,836-acre-foot (9,666,000 m3) reservoir.[41]

The Cascade Canal was completed in 1915, delivering about 5,462 acre feet (6,737,000 m3) of water from Fourmile Lake in the Klamath River watershed 4.5 miles (7.2 km) southwest to Fish Lake in the Rogue River watershed.[5][40][42] The temporary Fish Lake Dam was also replaced by a permanent earthfill dam.[5][40] It was later modified in 1922 and 1955.[43][44] In 1996 an auxiliary spillway was added. The dam stands 50 feet (15 m) high and has a length of 960 feet (293 m).[44]

In 1956, the United States Bureau of Reclamation awarded a contract to Portland, Oregon-based Lord Brothers to build the Deadwood Tunnel. The tunnel was finished in 1957. Howard Prairie Lake was completed in 1958, and is about 18 miles (29 km) east of Ashland.[40] Excess water is diverted from the South Fork, Beaver Dam Creek, and two of its tributaries 8.6 miles (14 km) south into the Deadwood Tunnel to supplement the lake and the surrounding regions.[5][36][45] Dead Indian Creek is also diverted into Howard Prairie Lake.[5] About 21.4 cubic feet per second (0.606 m3/s) annually, or about 16,500 acre feet (20,400,000 m3), was diverted into the Klamath River watershed between 1962 and 1999.[5][42]

The Howard Prairie Delivery Canal was completed in 1959, along with Keene Creek Reservoir, Cascade Tunnel, and Greensprings Tunnel. Water from Howard Prairie Lake is diverted into the canal west to Keene Creek Reservoir, about 16 miles (26 km) east of Ashland.[5][40] Nearby Hyatt Reservoir also provides water.[40][42] It is then piped through the mile-long Cascade Tunnel to the Greensprings Power Plant, which generates about 18 megawatts of power. Afterward, the water is conveyed from the power plant 2 miles (3 km) through the Greensprings Tunnel into Emigrant Creek, a tributary of Bear Creek.[5][40] An average of approximately 38,620 acre feet (47,640,000 m3) of water flows through the tunnel.[42] The water eventually ends up in Emigrant Lake, about 8 miles (10 km) southeast of Ashland, where it either continues along Bear Creek, or is diverted for irrigation.[40]

Butte Creek Mill

The Butte Creek Mill, originally named Snowy Butte Mill, was built in 1872 on the banks of Little Butte Creek about 5.5 miles (8.9 km) from its mouth.[16][46][47][48] A diversion dam was built in the 1880s to provide water for the turbine that powers the mill.[46] The dam was a damaging fish barrier in the watershed.[49][50] In 2005, the Rogue Basin Fish Access Team built a $250,000 concrete fish ladder to allow fish to swim past the dam.[47][49][50] A small weir made of boulders was built at the base of the ladder, creating a 9-inch (20 cm) jump between the creek and the ladder; however, the boulders were washed away in a severe storm just three months later, making the distance between them over 24 inches (61 cm).[49][50] The weir was rebuilt in 2008 for about $122,500,[47] with concrete instead of boulders.[50]

The mill is now included on the National Register of Historic Places, and is the only gristmill in Oregon to still grind flour.[46][48] It is also the oldest water-powered gristmill west of the Mississippi River.[51]

On Christmas morning, December 25, 2015, the store had a fire and was considered a total loss. There are plans to rebuild.[52][53] To assist in helping with the rebuild visit their website: buttecreekmill.com.[54]

Restoration

Intense flooding occurred throughout the Rogue Valley in 1955, and Little Butte Creek's meanders in the Denman Wildlife Area between Eagle Point and the Rogue River were blamed for severe erosion.[55][56] The 1.3-mile (2.1 km) section of the creek was subsequently bulldozed and straightened in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[55] The straightness forced water downward instead of outward like a typical creek, scouring the stream bed down to bedrock and creating an unsuitable habitat for wild salmon.[56] In 2007, a plan to divert the creek back into its old meanders was proposed.[55] The $700,000 project involved building engineered riffles and log jams and adding boulders, extending the creek by approximately 3,500 feet (1,100 m). It was completed in September 2011.[56][57]

Pollution

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has monitored Little Butte Creek for eight different parameters that affect water quality: temperature, oxygen saturation, pH, nutrients, bacteria, chemical contaminants such as pesticides and metals, turbidity, and alkalinity. Streams that exceed the standard level are then placed on the DEQ 303d list in accordance with the Clean Water Act. About 40 percent of the streams in the Little Butte Creek watershed were listed on the 2002 DEQ 303d list. The entire main stem exceeded the standard level for temperature, oxygen saturation, fecal coliforms (bacteria), and turbidity. The lower 6.5 miles (10 km) of the North Fork were listed for high temperature and elevated levels of E. coli, while the upper region was affected by chlorophyll a and pH levels. The South Fork was listed for turbidity and temperature.[4]

Overall, high temperature is the most common problem in the Little Butte Creek watershed. This is most likely caused by water diversion and depleted riparian zones. Approximately 53 percent of riparian zones in the watershed are damaged due to agriculture or deforestation, while 43 percent are classified as healthy. Another threat to healthy riparian zones are invasive blackberries, which crowd out native vegetation and provide little shade. The resulting higher water temperatures can be very harmful to anadromous fish. High concentration of bacteria is also an issue.[4]

In 2003, the Little Butte Creek Watershed Council rated the health of the Little Butte Creek watershed on a scale of 1 (slightly degraded) to 5 (severely degraded). Overall, the watershed received 2.95, or moderately degraded.[4] On the Oregon Water Quality Index (OWQI) used by DEQ, water quality scores can vary from 10 (worst) to 100 (ideal). The average for Little Butte Creek at RM 1.4 (RK 2.3) between 1998 and 2007 was 72 (poor) in the summer and 82 (fair) in the fall, winter, and spring.[58]

Recreation

The Little Butte Creek watershed contains several points of interest. Popular activities in and around Fish Lake include fishing, swimming, and boating. Two campgrounds are on the banks of the lake: Doe Point and the Fish Lake Resort. Several trails in the area lead to the much larger Pacific Crest Trail.[26] Two snowparks are on Oregon Route 140.[9]

The Eagle Point Golf Course is in the watershed,[4] built in 1995 by the world-renowned golf course architect Robert Trent Jones, Jr.[59] Another course, Stone Ridge Golf Course, is near Agate Lake.[4] The Butte Creek Mill and the Antelope and Lost Creek covered bridges are also popular attractions. Several historic structures can be found in Eagle Point, including the Eagle Point Museum, built in 1925 as the Long Mountain School, and the Walter Wood House, constructed in 1879.[60] The Denman Wildlife Area is at the mouth of Little Butte Creek, as is nearby TouVelle State Park.[16]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- Source elevation derived from the GNIS mouth elevations of the north and south forks.[1]

- The average discharge rate for this location was calculated by adding the average annual discharge rates for the total number of water years for which data was available and dividing by the total number of water years.[6]

- Source elevation derived from Google Earth search using Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) source coordinates.[1]

References

- GNIS North Fork 1980; GNIS South Fork 1980.

- GNIS Little Butte Creek 1980.

- TopoQuest Lakecreek Quadrangle.

- Little Butte Creek Watershed Council 2003.

- USBR & October 2009.

- USGS 14348000 Surface-Water.

- USGS 14348000 Water Data.

- USGS 14348000 Peak Streamflow.

- Benchmark Maps 2010, pp. 96–97.

- Schaffer & Selters 2004, p. 81.

- TopoQuest Robinson Butte Quadrangle.

- Shewey 2007, p. 85.

- TopoQuest Brownsboro Quadrangle.

- TopoQuest Eagle Point Quadrangle, Eagle Point.

- TopoQuest Eagle Point Quadrangle, Agate Road.

- TopoQuest Sams Valley Quadrangle.

- USGS 14344500.

- USGS 14343000.

- USGS 14342500.

- USGS 14341500 Surface-Water.

- USGS 14341500 Peak Streamflow.

- USGS 14341500 Water Data.

- Newell & US Census Bureau 1894, p. 210.

- Teal & Oregon Conservation Commission 1912, p. 43.

- FWS 1975.

- Ostertag & Ostertag 2005, p. 241.

- Gabrielson 1931, p. 111.

- Verts & Carraway 1998, p. 516; Maser & Cross 1981, p. 25.

- Wade 1997, p. 87.

- "Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast Recovery Domain 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation of Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast Coho Salmon ESU" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrations. 2011. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- Schwartz 1997, p. 11; Allen, Dixon & American Museum of Natural History 1907, p. 386.

- McArthur & McArthur 2003, p. 79.

- Oregon Historical Society 1903, p. 234; Bancroft & Victor 1888, p. 372.

- Bancroft & Victor 1888, p. 388.

- Ruby & Brown 1988, p. 118.

- BLM 2006, p. 6.

- Gaston 1912, p. 307.

- USGS & Pardee 1922, p. 214.

- Friedman 1990, p. 743.

- Linenberger 1999.

- USBR General 2009; USBR Hydraulics & Hydrology 2009.

- La Marche 2001.

- USBR General 2009.

- USBR Overview 2009.

- USBR Rogue River Basin Project.

- Butte Creek Mill.

- ODFW 2008.

- Barr 2004, p. 266.

- Freeman & March 1, 2008.

- Freeman & October 3, 2008.

- Bartlett 2009.

- "KDRV.com | KDRV.com - Medford, OR | Breaking News, Weather & Sports". kdrv.com. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- Eastman, Janet (November 24, 2018). "A state of change for Belushi and Oregon: After Oregon changed him, actor is working to return the favor". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. pp. A1, A6. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- "Butte Creek Mill". Butte Creek Mill. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- Freeman 2007.

- Freeman & May 26, 2009.

- Freeman & February 23, 2009; Freeman 2011.

- Oregon DEQ 2008.

- City of Eagle Point.

- Eagle Point & the Upper Rogue Chamber of Commerce.

Bibliography

Books

- Allen, Joel; Dixon, Roland; American Museum of Natural History (1907). "Article 5, The Shasta". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 17. New York: American Museum of Natural History. OCLC 497632.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers (1918). Bulletin of the American Institute of Mining Engineers. 140. American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers. OCLC 446077964.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bancroft, Hubert; Victor, Frances (1888). History of Oregon. San Francisco, California: The History Company. OCLC 258490428.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barr, Tom (2004) [First published 1997]. Scenic Driving Oregon (2nd ed.). Helena, Montana: Morris Book Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7627-3032-2. OCLC 55892911.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Ralph (1990). In Search of Western Oregon. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. ISBN 978-0-87004-332-1. OCLC 22111690.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gabrielson, Ira (May–June 1931). "The Birds of the Rogue River Valley, Oregon". The Condor. University of California Press. 33 (3): 110–121. doi:10.2307/1363576. ISSN 0010-5422. JSTOR 1363576. OCLC 478264799.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaston, Joseph (1912). The centennial history of Oregon, 1811–1912. 3. Chicago, Illinois: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. OCLC 1656126.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0875952772.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newell, Frederick; United States Census Bureau (1894). Report on Agriculture by Irrigation in the Western Part of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 6835279.

- Oregon Historical Society (1903). The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 4. W. H. Leeds. OCLC 448780533.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ostertag, Rhonda; Ostertag, George (2005) [First published 1999]. Camping Oregon (2nd ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: Morris Books Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7627-3643-0. OCLC 57514764.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ruby, Robert; Brown, John (1988). Indians of the Pacific North West. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2113-0. OCLC 7272798.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaffer, Jeffrey; Selters, Andy (2004) [First published 1974]. Pacific Crest Trail (7th ed.). Berkeley, California: Wilderness Press. ISBN 978-0-89997-375-3. OCLC 57470533.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwartz, E. A. (1997). The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850–1980. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2906-8. OCLC 35103496.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shewey, John (2007). Complete Angler's Guide to Oregon. Belgrade, Montana: Wilderness Adventures Press. ISBN 978-1-932098-31-0. OCLC 145339074.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Teal, Joseph; Oregon Conservation Commission (1912). Report of the Oregon Conservation Commission to the Governor. Salem, Oregon: W. S. Duniway. OCLC 32630207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- United States Geological Survey; Pardee, J. T. (August 8, 1921). Deposits on Manganese Ore in Montana, Utah, Oregon, and Washington. 725-C. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 6036257.

- Verts, B. J.; Carraway, Leslie (1998). Land Mammals of Oregon. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21199-5. OCLC 37211383.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wade, Nicholas (1997). The Science Times Book of Fish. New York City, New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-604-4. OCLC 36817305.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

News articles

- Bartlett, Stephanie (August 19, 2009). "Butte CreeK Mill". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Fish ladder repair opens Little Butte Creek to migrating fish". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. October 1, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- Freeman, Mark (May 26, 2009). "Creek effort balances technology, habitat". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- Freeman, Mark (March 1, 2008). "Effort afoot to fix Butte Creek Mill dam". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- Freeman, Mark (February 23, 2009). "Project looks to return tributary to its original channel". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- Freeman, Mark (October 3, 2008). "Rebuilt fish ladder clears the way for Chinook salmon". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- Freeman, Mark (September 15, 2011). "The Trickle-Down Effect". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freeman, Mark (January 8, 2007). "Turning back". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved September 21, 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Websites

- "Fish Lake Dam: General". United States Bureau of Reclamation. April 30, 2009. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Fish Lake Dam: Hydraulics & Hydrology". United States Bureau of Reclamation. April 30, 2009. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Fish Lake Dam: Overview". United States Bureau of Reclamation. April 30, 2009. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Eagle Point Golf Course". City of Eagle Point. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- "Mill History – A National Treasure". Butte Creek Mill. Archived from the original on 2011-10-20. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- "Recreation & Attractions: Living History". Eagle Point & the Upper Rogue Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- "Rogue River Basin Project Talent Division – Oregon". United States Bureau of Reclamation. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- "USGS 14341500 South Fork Little Butte Cr Nr Lakecreek, Oreg.: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "USGS 14341500 South Fork Little Butte Cr Nr Lakecreek, Oreg.: Peak Streamflow". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "USGS 14341500 South Fork Little Butte Cr Nr Lakecreek, Oreg.: Annual Water Data Reports". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "USGS 14342500 No Fk Little Butte Cr At F L Nr Lakecreek, Oreg.: Annual Water Data Reports". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- "USGS 14343000 No Fk Little Butte Cr Nr Lakecreek, Oreg.: Peak Streamflow". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- "USGS 14344500 Nf Ltl Bute Cr Ab Intke Canl Lkecreek Oreg: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- "USGS 14348000 Little Butte Cr Bl Eagle Point Oreg: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "USGS 14348000 Little Butte Cr Bl Eagle Point Oreg: Peak Streamflow". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- "USGS 14348000 Little Butte Cr Bl Eagle Point Oreg: Annual Water Data Reports". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

Other

- Benchmark Maps (2010). Oregon Road and Recreation Atlas (Map) (4th ed.). 1:225,000. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-929591-62-9. OCLC 466904230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Biological Assessment on the Future Operation and Maintenance of the Rogue River Basin Project" (PDF). United States Bureau of Reclamation. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- La Marche, Jonathan (February 22, 2001). Water Imports and Exports Between The Rogue and Upper Klamath Basin (Report). Archived from the original (DOC) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linenberger, Toni Rae (1999). "The Rogue River Basin Project Talent Division" (PDF). United States Bureau of Reclamation. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 23, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Little Butte Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- "Little Butte Creek Watershed Assessment" (ZIP). Little Butte Creek Watershed Council. August 2003. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- Maser, Chris; Cross, Steven (March 1981). "Notes on the Distribution of Oregon Bats" (PDF). Research Note PNW-37 9. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "North Fork Little Butte Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- "Oregon Water Quality Index Summary Report Water Years 1998–2007" (PDF). Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- "South Fork Little Butte Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- "The Distribution and Occurrence of the Birds of Jackson County, Oregon, and Surrounding Areas" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1975. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- United States Geological Survey (February 17, 2010). Brownsboro quadrangle (Topographic map). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 17, 2010 – via TopoQuest.

- United States Geological Survey (February 17, 2010). Eagle Point quadrangle, Eagle Point (Topographic map). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 17, 2010 – via TopoQuest.

- United States Geological Survey (February 17, 2010). Eagle Point quadrangle, Agate Road (Topographic map). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 17, 2010 – via TopoQuest.

- United States Geological Survey (January 9, 2010). Lakecreek quadrangle (Topographic map). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2010 – via TopoQuest.

- United States Geological Survey (January 9, 2010). Robinson Butte quadrangle (Topographic map). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2010 – via TopoQuest.

- United States Geological Survey (January 9, 2010). Sams Valley quadrangle (Topographic map). Reston, VA: United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 9, 2010 – via TopoQuest.

- "Water Quality Restoration Plan: North and South Forks Little Butte Creek Key Watershed" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. May 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

External links