Lithuania–Russia relations

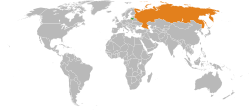

Lithuania–Russia relations refers to bilateral foreign relations between Lithuania and Russia. Lithuania has an embassy in Moscow and consulates in Saint Petersburg, Kaliningrad and Sovetsk. Russia has an embassy in Vilnius, with consulates in Klaipėda. The two countries share a common border through Kaliningrad Oblast.

| |

Lithuania |

Russia |

|---|---|

History

Lithuania and the Russian Empire

In 1795, Vilna Governorate (consisting of eleven uyezds or districts) and Slonim Governorate, were established by the Russian Empire after the third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Just a year later, on December 12, 1796, by order of Tsar Paul I they were merged into one governorate, called the Lithuanian Governorate, with its capital in Vilnius.[1] By order of Tsar Alexander I on September 9, 1801, the Lithuanian Governorate was split into the Lithuania-Vilnius Governorate and the Lithuania-Grodno Governorate. After 39 years, the word "Lithuania" was dropped from the two names by Nicholas I.[2] In 1843, another administrative reform took place, creating the Kaunas Governorate (Kovno in Russian) out of seven western districts of the Vilnius Governorate, including all of Žemaitija. The Vilnius Governorate received three additional districts: Vileyka and Dzisna from the Minsk Governorate and Lida from Grodno Governorate.[3] It was divided to districts of Vilnius, Trakai, Disna, Oshmyany, Lida, Vileyka and Sventiany. This arrangement remained unchanged until World War I. A part of the Vilnius Governorate was then included in the Lithuania District of Ober-Ost, formed by the occupying German Empire.

During the Polish-Soviet War, the area was annexed by Poland. The Council of Ambassadors and the international community (with the exception of Lithuania) recognized Polish sovereignty over Vilnus region in 1923.[4] In 1923, the Wilno Voivodeship was created, which existed until 1939, when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania and Poland and returned most of the Polish-annexed land to Lithuania.

During the 1905 Russian Revolution, a large congress of Lithuanian representatives in Vilnius known as the Great Seimas of Vilnius demanded provincial autonomy for Lithuania (by which they meant the northwestern portion of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania)[5] on 5 December of that year. The tsarist regime made a number of concessions as the result of the 1905 uprising. The Baltic states once again were permitted to use their native languages in schooling and public discourse, and Catholic churches were built in Lithuania. Latin characters replaced the Cyrillic alphabet that had been forced upon Lithuanians for four decades. But not even Russian liberals were prepared to concede autonomy similar to that that had already existed in Estonia and Latvia, albeit under Baltic German hegemony. Many Baltic Germans looked toward aligning the Baltics (Lithuania and Courland in particular) with Germany.[6]

After the outbreak of hostilities in World War I, Germany occupied Lithuania and Courland in 1915. Vilnius fell to the Germans on 19 September 1915. An alliance with Germany in opposition to both tsarist Russia and Lithuanian nationalism became for the Baltic Germans a real possibility.[6] Lithuania was incorporated into Ober Ost under a German government of occupation.[7] As open annexation could result in a public-relations backlash, the Germans planned to form a network of formally independent states that would in fact be dependent on Germany.[8]

Lithuania and Soviet Russia

As the combined result of the October Revolution and the end of World War I, the power in the territory of Lithuania was contested by several political forces: national, Polish, and Moscow-backed Communist factions. The Council of Lithuania signed the Act of Independence of Lithuania. During the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–19, which followed the retreating German troops, a Lithuanian–Soviet War was fought between the newly independent Lithuania and the Soviet Russia. At the same time period the Soviet Russia had relations with the short-lived Communist puppet states: Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic which was soon merged into the Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In April 1920, The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania was elected and first met the following May. In June it adopted the third provisional constitution and on July 12, 1920, signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. In the treaty the Soviet Union recognized fully independent Lithuania and its claims to the disputed Vilnius Region; Lithuania secretly allowed the Soviet forces passage through its territory as they moved against Poland.[9] On July 14, 1920, the advancing Soviet army captured Vilnius for a second time from Polish forces. The city was returned to Lithuanians on August 26, 1920, following the defeat of the Soviet offensive. The victorious Polish army returned and the Soviet–Lithuanian Treaty increased hostilities between Poland and Lithuania. To prevent further fighting, the Suwałki Agreement was signed with Poland on October 7, 1920; it left Vilnius on the Lithuanian side of the armistice line.[10] It never went into effect, however, because Polish General Lucjan Żeligowski, acting on Józef Piłsudski's orders, staged the Żeligowski's Mutiny, a military action presented as a mutiny.[10] He invaded Lithuania on October 8, 1920, captured Vilnius the following day, and established a short-lived Republic of Central Lithuania in eastern Lithuania on October 12, 1920. The "Republic" was a part of Piłsudski's federalist scheme, which never materialized due to opposition from both Polish and Lithuanian nationalists.[10]

On 30 December 1922, Soviet Russia was incorporated into the Soviet Union, and the latter state inherited the Lithuania–Russia relations.

Lithuania and the Soviet Union

1920s and 1930s

The Third Seimas of Lithuania was elected in May 1926. For the first time, the bloc led by the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party lost their majority and went into opposition. It was sharply criticized for signing the Soviet–Lithuanian Non-Aggression Pact (even though it affirmed Soviet recognition of Lithuanian claims to Poland-held Vilnius).[11]

World War II

At the beginning of World War II, when the Soviet Union invaded Poland, Soviet troops took over Vilnius Region, which belonged to Interwar Poland, but according to the 1920 and 1926 Soviet–Lithuanian treaties was recognized to Lithuania.[12] As a result, Soviets and Germans re-negotiated the secret protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. On September 28, 1939, they signed the Boundary and Friendship Treaty.[13] Its secret attachment detailed that to compensate the Soviet Union for German-occupied Polish territories, Germany would transfer Lithuania, except for a small territory in Suvalkija, to the Soviet sphere of influence.[14] The exchange of territories was also motivated by Soviet control of Vilnius: the Soviet Union could exert significant influence on the Lithuanian government, which claimed Vilnius to be its de jure capital.[15] In the secret protocols, both Soviet Union and Germany explicitly recognized Lithuanian interest in Vilnius.[16] Accordingly, by the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty of October 10, 1939, Lithuania would acquire about one fifth of the Vilnius Region, including Lithuania's historical capital, Vilnius, and in exchange would allow five Soviet military bases with 20,000 troops to be established across Lithuania.

After months of intense propaganda and diplomatic pressure, the Soviets issued an ultimatum on June 14, 1940 [17] Soviets accused Lithuania of violating the treaty and abducting Russian soldiers from their bases.[14] Soviets demanded that a new government, which would comply with the Mutual Assistance Treaty, would be formed and that an unspecified number of Soviet troops would be admitted to Lithuania.[18] With Soviet troops already in the country, it was impossible to mount military resistance.[17] Soviets took control of government institutions, installed a new pro-Soviet government, and announced elections to the People's Seimas. Proclaimed Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was incorporated into the Soviet Union on August 3, 1940.[19] One local Communist party emerged from underground with 1500 members in Lithuania.[20]

Soviet deportations from Lithuania

During the occupation of Lithuania, at least 130,000 people, 70% of them women and children,[21] were forcibly transported to labor camps and other forced settlements in remote parts of the Soviet Union, such as the Irkutsk Oblast and Krasnoyarsk Krai. Among the deportees were about 4,500 Poles.[22] These deportations did not include Lithuanian partisans or political prisoners (approximately 150,000 people) deported to Gulag forced labor camps.[23] Deportations of the civilians served a double purpose: repressing resistance to Sovietization policies in Lithuania and providing free labor in sparsely inhabited areas of the Soviet Union. Approximately 28,000 of Lithuanian deportees died in exile due to poor living conditions.

Second Soviet occupation

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

In the summer of 1944, the Soviet Red Army reached eastern Lithuania.[24] By July 1944, the area around Vilnius came under control of the Polish Resistance fighters of the Armia Krajowa, who also attempted a takeover of the German-held city during the ill-fated Operation Ostra Brama.[25] The Red Army captured Vilnius with Polish help on 13 July.[25] The Soviet Union re-occupied Lithuania and Joseph Stalin re-established the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1944 with its capital in Vilnius.[25] The Soviets secured the passive agreement of the United States and Great Britain (see Yalta Conference and Potsdam Agreement) to this annexation. By January 1945, the Soviet forces captured Klaipėda on the Baltic coast. The heaviest physical losses in Lithuania during World War II were suffered in 1944–45, when the Red Army pushed out the Nazi invaders.[26] It is estimated that Lithuania lost 780,000 people between 1940 and 1954 under the Nazi and Soviet occupations.[27]

After Stalin's death in 1953, the deportees were slowly and gradually released. The last deportees were released only in 1963. Some 60,000 managed to return to Lithuania, while 30,000 were prohibited from settling back in their homeland. Soviet authorities encouraged the immigration of non-Lithuanian workers, especially Russians, as a way of integrating Lithuania into the Soviet Union and encouraging industrial development,[27] but in Lithuania this process did not assume the massive scale experienced by other European Soviet republics.[28]

To a great extent, Lithuanization rather than Russification took place in postwar Vilnius and elements of a national revival characterize the period of Lithuania's existence as a Soviet republic.[24] Lithuania's boundaries and political integrity were determined by Joseph Stalin's decision to grant Vilnius to the Lithuanian SSR again in 1944. Subsequently, most Poles were resettled from Vilnius (but only a minority from the countryside and other parts of the Lithuanian SSR)[h] by the implementation of Soviet and Lithuanian communist policies that mandated their partial replacement by Russian immigrants. Vilnius was then increasingly settled by Lithuanians and assimilated by Lithuanian culture, which fulfilled, albeit under the oppressive and limiting conditions of the Soviet rule, the long-held dream of Lithuanian nationalists.[29] The economy of Lithuania did well in comparison with other regions of the Soviet Union.

In 1956 and 1957, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union approved releases of larger groups of the deportees, including the Lithuanians. Deportees started returning in large numbers creating difficulties for local communists – deportees would petition for return of their confiscated property, were generally considered unreliable and required special surveillance. Soviet Lithuanian officials, including Antanas Sniečkus, drafted local administrative measures prohibiting deportee return and petitioned Moscow to enact national policies to that effect.[30] In May 1958, the Soviet Union revised its policy regarding the remaining deportees: all those who were not involved with the Lithuanian partisans were released, but without the right to return to Lithuania.[31] The last Lithuanians—the partisan relatives and the partisans—were released only in 1960 and 1963 respectively.[32] Majority of the deportees released in May 1958 and later never returned to Lithuania.[33]

About 60,000 deportees returned to Lithuania.[34] Upon return, they faced further difficulties: their property was long looted and divided up by strangers, they faced discrimination for jobs and social guarantees, their children were denied higher education. Former deportees, resistance members, and their children were not allowed to integrate into the society. That created a permanent group of people that opposed the regime and continued non-violent resistance.[35]

Because of the United States and the United Kingdom, the allies of the Soviet Union were against Nazi Germany during World War II, recognized the occupation of the Republic of Lithuania at Yalta Conference in 1945 de facto, the governments of the rest of the western democracies did not recognize the seizure of Lithuania by the Soviet Union in 1940 and in 1944 de jure according to the Sumner Welles' declaration of 23 July 1940;[36] Due to the situation, many western countries continue to recognize Lithuania as an independent, sovereign de jure state subject to international law represented by the legations appointed by the pre-1940 Baltic states which functioned in various places through the Lithuanian Diplomatic Service.

Lithuania declared sovereignty on its territory on 18 May 1989 and declared independence from the Soviet Union on 11 March 1990 as the Republic of Lithuania, and was the first Soviet republic to do so. All legal ties of the Soviet Union's sovereignty over the republic were cut as Lithuania declared the restitution of its independence. The Soviet Union claimed that this declaration was illegal, as Lithuania had to follow the process of secession mandated in the Soviet Constitution if it wanted to leave. Most other countries followed suit after the failed coup in August, with the State Council of the Soviet Union recognized Lithuania's independence on 6 September 1991.

Lithuania and the Russian Federation

On 27 July 1991, the Russian government re-recognized Lithuania and the two countries re-established diplomatic relations on 9 October 1991. President Boris Yeltsin and President Vytautas Landsbergis met to discuss economic ties.

The Russian troops stayed in Lithuania for an additional three years, as Boris Yeltsin linked the issue of Russian minorities with troop withdrawals. Lithuania was the first to have the Russian troops withdrawn from its territory in August 1993.

Following Russia's military intervention in Ukraine, concerns about the geopolitical environment led Lithuania to begin preparing for a Russian invasion. In December 2014, Russia carried out a military drill in nearby Kaliningrad with 55 naval vessels and 9000 soldiers.[37] In 2015, Lithuanian Chief of Defence Jonas Vytautas Žukas announced plans to reinstate conscription, which ended in 2008, to bolster the ranks of the Lithuanian Armed Forces. The Ministry of National Defence also published a 98-page manual for citizens to prepare them for armed conflict and occupation.[38]

Ambassadors

Lithuanian

- Egidijus Bičkauskas (1993-1998, plenipotentiary representative)

- Romualdas Kozyrovičius (1999-2000, 2006-2007)

- Zenonas Namavičius (2000-2002)

- Rimantas Šidlauskas (2002-2008)

- Antanas Vinkus (2009-2011)

- Renatas Norkus (2012-2014)

- Remigijus Motuzas (2015-)

Russian

See ru:Список послов СССР и России в Литве (List of ambassadors of the USSR and Russia in Lithuania)

- Vladimir Chkhikvadze (2008-2013)

- Aleksandr Udaltsov (2013-)

References

- Kulakauskas, Antanas (2002). "Administracinės reformos". Gimtoji istorija. Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Elektroninės leidybos namai. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4. Archived from the original on 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- "Литовская губерния". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1890–1906.

- Simas Sužiedėlis, ed. (1970–1978). "Administration". Encyclopedia Lituanica. I. Boston, Massachusetts: Juozas Kapočius. pp. 17–21. LCC 74-114275.

- Jan Tomasz Gross. Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton University Press. 2002. p. 3.

- Snyder (2003), p. 53

- Hiden, John and Salmon, Patrick. The Baltic Nations and Europe. London: Longman. 1994.

- Maksimaitis, Mindaugas (2005). Lietuvos valstybės konstitucijų istorija (XX a. pirmoji pusė) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Justitia. pp. 35–36. ISBN 9955-616-09-1.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (September 1999). "Chapter 1: Restoration of the State". In Ed. Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 20–28. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- Snyder (2003), p. 63

- Snyder (2003), p. 63-65

- Snyder (2003), p. 78–79

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1991). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Šviesa. pp. 137–140. ISBN 5-430-01059-6.

- Kershaw, Ian (2007). Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions that Changed the World, 1940–1941. Penguin Group. p. 259. ISBN 1-59420-123-4.

- Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Judith B. Sedaitis (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. WestviewPress. p. 47. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (2007). Lithuania 1940: Revolution from Above. On the Boundary of Two Worlds: Identity, Freedom, and Moral Imagination in the Baltics. Rodopi. p. 13. ISBN 90-420-2225-6.

- Shtromas, Alexander; Robert K. Faulkner; Daniel J. Mahoney (2003). Totalitarianism and the Prospects for World Order. Lexington Books. p. 246. ISBN 0-7391-0534-5.

- Lane, Thomas (2001). Lithuania: Stepping Westward. Routledge. pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-415-26731-5.

- Slusser, Robert M.; Jan F. Triska (1959). A Calendar of Soviet Treaties, 1917–1957. Stanford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-8047-0587-9.

- Snyder, Timothy (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. pp. 81–83. ISBN 0-300-10586-X.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The history of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 117. ISBN 0-313-32355-0.

- Anušauskas (2005), p. 302

- Stravinskienė (2012), p. 44

- Anušauskas (2005), p. 289

- Snyder (2003), p. 72

- Snyder (2003), p. 88

- Saulius Sužiedelis, Zagłada Żydów, piekło Litwinów [Extermination of the Jews, hell for the Lithuanians]. Zagłada Żydów, piekło Litwinów Gazeta Wyborcza wyborcza.pl 28.11.2013

- Lithuania profile: history. U.S. Department of State Background Notes. Last accessed on 02 June 2013

- Snyder (2003), p. 94

- Snyder (2003), pp. 91–93

- Anušauskas (2005), p. 415

- Anušauskas (1996), p. 396

- Anušauskas (2005), pp. 417–418

- Anušauskas (1996), pp. 397–398

- Anušauskas (2005), p. 418

- Vardys (1997), p. 84

- Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary of State at U.S Department of State

- Sytas, Andrius (February 24, 2015). "Worried over Russia, Lithuania plans military conscription". Reuters.

- Cichowlas, Ola (March 16, 2015). "Lithuania prepares for a feared Russian invasion". Reuters.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of Lithuania and Russia. |

- (in Russian) Documents on the Lithuania–Russia relationship from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- (in Russian and Lithuanian) Embassy of Russia in Vilnius

- (in Russian and Lithuanian) Embassy of Lithuania in Moscow

- Встреча Путина и Грибаускайте