Lindridge House

Lindridge House was a large 17th-century mansion (with 20th-century alterations), one of the finest in the south-west[1] situated about 1 mile south of Ideford in the parish of Bishopsteignton, Devon, about 4 1/2 miles NE of Newton Abbot. It was destroyed by fire on 25 April 1963 and its ruins were finally demolished in the early 1990s, upon which was built a housing development.

The gardens have been restored and are Grade II listed in the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[2]

Descent

Bishops of Exeter

The site of Lindridge House is situated 1/2 mile NW of the church in the parish of Bishopsteignton.[3]

Dudley

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, in 1549 the estate was acquired by Sir Andrew Dudley, KG (c. 1507 – 1559), a soldier, courtier (Groom of the Bedchamber) and diplomat, and a younger brother of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland. He held it only for a short period.

Duke

In 1550 Dudley sold "Lyndrygge" to Richard Duke (c. 1515 – 1572) of London and Otterton, Devon, together with the "lordships and Manors of Bishops Teignton, Radway and West "Teyngmouth" and the rectories and church of Bishops Teignton and Radway". A chief rent of £20 was payable to Dudley after the death of "John, Bishop of Exeter",[4] presumably Bishop John Vesey (died 1554). Richard Duke was MP for Weymouth in 1545, for Dartmouth in 1547 and Sheriff of Devon in 1563–1564. His position as Clerk of the Court of Augmentations from its inception in 1536 to 1554 gave him the opportunity of buying many lands of dissolved monasteries. In 1540 he purchased the large manors of East Budleigh and Otterton, where his family had lived for many generations.[5] From Duke it reverted to the crown in 1572.[6]

Martin

In 1614, the estate was purchased for £2,900 by the lawyer Richard Martin (1570–1618), born in nearby Otterton, a member of the Middle Temple and MP for Barnstaple in 1601 and twice for Christchurch, in 1604 and 1614.[7] He started to rebuild the house in 1617, which was completed by his brother and heir Thomas Martin (died 1620), mayor of Exeter.[6] Thomas married Rhoda (died 1651), of unknown family, who survived him 31 years and remarried George Wescombe. It was inherited by Thomas's son William Martin (died 1640), who married Agnes Cove of Bishopsteignton.[6] During the Civil War William was a Royalist and with his neighbour Hugh Clifford of Ugbrooke, who commanded a regiment of foot soldiers, he marched north to fight against the Scots. He was wounded and died at Lindridge in March 1640.[6] Hugh Clifford's son Thomas Clifford, 1st Baron Clifford of Chudleigh (1630–1673) married Elizabeth Martin (died 1709), from which marriage the present Barons Clifford of Chudleigh are descended. It was sold by the Martin family in 1660 to Sir Peter Lear.

Lear

Sir Peter Lear, 1st Baronet (died c. 1684), purchased the house in 1660. He was born the son of a yeoman in Ipplepen in Devon and after 1645 acquired large plantations in Barbados[8] He married Susannah Lant (died 1713) by whom he had 9 children, all of whom died as infants between the years 1664 and 1680.[9] He started a major remodelling of the house, completed in 1673 as evidenced by a datestone on the chimney, which resulted in the demolition of the two wings of the former building leaving the central section 9-bays wide by 6 deep. He created a particularly ornate interior with exceptionally fine wainscotting, doors and fireplaces.[10] The ornamental ceilings in the ballroom, measuring 50 ft × 30 ft, and morning toom were particularly noted [1] and the Devon historian Polwhele, who visited in 1793, described the ballroom thus: "It has six windows and its rich, carved work, copper ceiling,[11] and the panels of burnished gold, are highly ornamental". The Lear baronetcy, "of London", was created for him by King Charles II on 2 July 1660, shortly after the Restoration, but as he left no children, it became extinct upon his death. However, clearly as a special favour from the crown, shortly before his death a second baronetcy, "of Lindridge", was created for him on 2 August 1683 with special remainder to his nephews. His eldest nephew, then aged 11, was Sir Thomas Lear, 2nd Baronet (1672–1705), of Lindridge, MP for Ashburton 1701–1705. Thomas married Isabella Courtenay, daughter of Sir William Courtenay, 1st Baronet of Powderham, but both died in their early thirties, in the same year, without children.[9] The baronetcy became extinct upon the death of his brother Sir John Lear, 3rd Baronet (died c. 1736), who had married the daughter of Christopher Wolston, gent., of Devon, and who left a sole heiress Mary. In the church of St. John the Baptist, Bishopsteignton, are monuments to Sir Peter Lear, baronet and Sir Thomas Lear, baronet (died 1705).

Comyns

Mary Lear, the sole daughter and after 1736 the heiress of the 2nd baronet, married in about 1724 to Sir Thomas Tipping, 2nd Baronet (1700–1725), who died the next year aged 25, without children. She remarried in about 1726 to Thomas Comyns.[12] Mary seems to have died before 1732, four years before the death of her father, as Thomas Comyns, who was described as "of Lindridge", was a party in the settlement made upon his marriage to Dame Mary Wolston of Staverton, dated 20 October 1732.[13] Comyns thus appears to have inherited Lindridge from his father-in-law who died in 1736. Comyns still held Lindridge in 1738[14] but had sold part of the estate, under an Act of Parliament,[15] to "Dr Finney" [9][16] apparently Protodorus Finney Esq., (died 1734), of Blagdon, a lawyer of Lyon's Inn, Middlesex.

Baring

In 1747 Lindridge was purchased for £8,000 by John Baring I (1697–1748), of Larkbeare House (38 Holloway Road), Exeter. Baring was one of the wealthiest cloth merchants of Exeter, a Lutheran born in Bremen, Germany. His heir was his son John Baring II (1730–1816), who founded with his younger brother Francis Baring (1740–1810), created the 1st Baring baronet "of Larkbeer" in 1793, the company which became Barings Bank. In 1755 he purchased Mount Radford House,[17] Exeter, which became his home and where he died, and served as MP for Exeter in 1776, and was Sheriff of Devon in 1776.[18] In 1765 he sold Lindridge to John Line (died 1777).

Line

John Line (died 1777) was a wealthy self made building contractor who with his partners Thomas Parlby (1727–1802) and James I Templer (1722–1782), constructed new Royal Navy dockyards at Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth. All three appear to have originated in Kent, near Rotherhithe, but moved to Devon following their acquisition of the government contract to reconstruct and expand Plymouth dockyard, to meet the increased space needed by the Royal Navy which had been expanded due to the French invasion threat. Templer had purchased in the same year of 1765 the manor of Teigngrace where in 1780 he built the grand late-Palladian Stover House. John Line served as Sheriff of Devon in 1774.[19] He died of smallpox, leaving left a daughter Eliza Ann, living with him at his death at Lindridge, to whom he bequeathed the sum of £2,000. Probate was granted on 10 May 1777 to his widow Jane Shubrick (1751–1813), his sole executrix, the daughter of Thomas I Shubrick[20] who had gone to America[21] with his brother Richard I Shubrick of Quenby Plantation, South Carolina, and who became a member of the first legislative council of South Carolina.[22] Jane's brother was Col. Thomas II Shubrick (1756–1810) of Belvedere, South Carolina, a plantation owner, who in 1773 entered the Middle Temple in London for his legal training but later moved to America where he fought with distinction on the American side in the American War of Independence,[23] and whose son was John Templer Shubrick (1788–1815) a distinguished officer in the US Navy. He left all his property to his widow Jane for her life and thereafter in trust to his godson Henry Line Templer, for his life, with remainder to his lawful male issue in tail male. The trustees were his partner James Templer "of Stover Lodge", and his son Rev John Templer and George Cross (1740–1779)[24] of Duryarde in Exeter.[25]

Templer

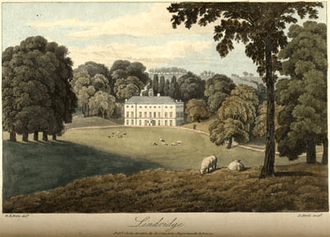

John Line's heir was his godson Lt-Col. Henry Line Templer (1765–1818),[16] 10th Lt Dragoons and one of the Prince Regent's household,[26] whose monument exists in Teigngrace Church, the youngest son of his partner James Templer. Henry married Mary Rogers, daughter of Sir Frederick Leman Rogers, 7th Baronet (1782–1851).[27] He had four sons and 5 daughters.[26] In 1778, the year after her husband's death, John Line's young widow Jane (died 1813)[28] remarried to Rev. John Templer (1751–1832), the second son of her first husband's partner James Templer and the elder brother of her first husband's heir, Henry Line Templer, after whose early death in 1818 Lindridge was purchased from his heirs by his brother Rev. John Templer.[16] Jane died in 1813, having predeceased her second husband, who continued to live on at Lindridge, keeping a pack of harriers there, until his death in 1832, nursed in his old age by his widowed sister Lady Anne de la Pole (died 1832), the widow of Sir John de la Pole, 6th Baronet (1757–1799) of Shute, Devon, as is recorded on her mural monument in Shute Church. Lady Anne died also at Lindridge two months after her brother, and the estate descended to her and her brother's three-year-old great nephew James George John Templar (1829–1883), son of Rev James Ackland Templer (1797–1866) by his wife Anne Mason, daughter of Bryant Mason.[29] Whilst credible accounts, including that quoted above of Lysons, state that John Line bequeathed Lindridge to his godson Henry Line Templer, (born 1765) the youngest son of his partner James Templer (died 1782), but its descent was certainly described by Rev. John Swete (died 1821) who passed by it in July 1795, and painted it in watercolour, as "by the decease of the last proprietor Mr Line it was by his widow convey'd by marriage to the Rev'd John Templar".[30] Swete described Lindridge in July 1795 as follows:[31]

There is wanting only water at Lindridge to render it one of the finest spots in the county, but it lies too near Haldown to have a stream of any size, and perhaps amid scenery which is indebted to nature for all its charms it were better to be as it is without a sheet of water altogether, than to have it introduced by art which could not be wholly concealed. The house is a handsome pile and of considerable size though in no wise so large as the antient one which (it is said) covered over no less than an acre of ground. This magnificent building was a possession of the Martyns, whose seats at successive periods ( among others) I have already noticed at Cockington, Dartington and Oxton. (Swete's own home, inherited from his paternal grandmother, a Martyn) A daughter of the last Martyn of Lindridge, a co-heiress, was married to the Lord Treasurer Clifford, the first of the family that was ennobled, about the middle of the last century, which connection between the two families seems to have been kept up to the time of my relative and predecessor at Oxton, whose name was Wm. Clifford Martyn. From the Martyns it past to the Lears and others, till by the decease of the last proprietor Mr Line it was by his widow convey'd by marriage to the Rev'd John Templar. Of the old house there is one room yet retained and which has undergone but little alteration, its dimensions are 50 × 30 and by its size and costly decorations we may collect no inadequate idea of the opulence of the family. Of the ornamental part tho' the room was fitted up in 1673 there are yet in being some rich carved work and highly burnished gilding, the expence of which latter article (according to the disbursements in the steward's book) amounted to no less a sum than 500 pounds. I past from this charming spot, through an avenue at the back of the house, into the public road...

Swete's own eldest son and heir John Beaumont Swete (1788–1867) married Mary Templer (1794–1886), a daughter of Henry Line Templer and Mary Rogers. The young James' father was George Templer (1755–1819), of Shapwick, Somerset, which manor he had purchased from Dennis Rolle of Stevenstone. George Templer, the brother of Rev. John Templer and of Lady Anne de la Pole, was an officer of the Honourable East India Company and had married in 1781 Jane Paul, the eldest daughter of Henry Paul, of West Monkton, Somerset, a wealthy officer also in the service of the HEIC.[32] James George John Templer (died 1883) married Frances Mortimer and had four sons and four daughters. His eldest son and heir was John George Edmund Templer (1855–1924), JP, Captain in the Highland Light Infantry and Captain and honorary Major in the Royal 1st Devon Imperial Yeomanry.

Cable

Sometime before 1910 John Templer (died 1924) let Lindridge to Sir Ernest Cable (1859–1927), later created 1st Baron Cable of Ideford in 1921, at an annual rent of £380. Cable was an Indian-born British merchant and financier. He served as Sheriff of Calcutta in 1905 and was knighted when George, Prince of Wales and his wife Mary of Teck visited the city in the following year.[33] He returned to England by 1913 and in 1916 was appointed High Sheriff of Devon.[34] The lease was increased to 40 years in 1915 at a rent of £643 per annum, whereupon Cable started making major alterations. In 1920 John Templar sold the freehold of Lindridge to Cable for £75,000, and died four years later leaving his next younger brother James Mortimer Templer (1858–1934), of Brampford House, Brampford Speke, Exeter, the senior representative of the Templer family.[32] The Templar family had made few changes to the house.[1] Cable's alterations between 1915 and 1916, to the design of James Ransome, gave Lindridge the external appearance of a Queen Anne house, with the plain stucco exterior having been replaced with a facing of red brick. Glazing bars were added to the sash windows and wooden shutters were added. An arched top was given to the uppermost central window of the south and east fronts and the parapets were removed. Stone urns were placed on the corners of the roof and formal gardens were added. The grounds were landscaped between 1913 and 1914 by James Ransome with Robert Veitch of Exeter and Edward White.[3] Cable and his wife had two daughters and one son, George, who was killed in action in the First World War in 1915.[35] His wife died in 1924 and Cable survived her for three years, dying in London in 1927; he was buried in Ideford on 31 March.[36] On his death the baronetcy became extinct.[36]

Benthall

%2C_Lady_Benthall%3B_National_Trust%2C_Benthall_Hall.jpg)

On the death of Lord Cable in 1927 the estate was inherited by his daughter Ruth, the wife of Sir Edward Benthall (died 1961), of Benthall Hall, Shropshire. In Kellys Directory of 1939 Lindridge was described as "the property and residence of Sir Edward Charles Benthall, the house is of stone, standing in a park of 145 acres, approached from Chudleigh by a double avenue of elms, and from Newton by a drive through a wood a mile in extent".[37] The Benthall's wealth had been located in India and was lost following nationalisation after Indian Independence in 1947.

%2C_KCSI%2C_as_a_Young_Man_%3B_National_Trust%2C_Benthall_Hall.jpg)

Sir Edward Benthall remained at Lindridge, but unable to afford the large staff needed to maintain the house, several rooms were closed-up. His wife spent most of her time in the South of France. On sir Edward's death in 1961 his son Michael Benthall inherited. In June 1962, Lady Benthall sold at auction most of the contents and fittings, including the 5 ft 6in × 3 ft 9in ballroom chandelier, which sold for £4,200.

Brady

Michael Benthall was based in London as director of the Old Vic theatre, and had little use for his Devon property which he sold to timber merchants, with two farms, for £60,000. The ancient trees in the park were cut down and sold. The house with 60 acres of land was then re-sold to Mr Brady of Brixham for £15,750. Brady at first stated his intention to be the restoration of the house and its use as his family home, but later announced plans for a development of 100 holiday chalets in the grounds, which scheme was rejected by the parish council.[1] Parts of the house were restored and with the garden it was opened to the public in 1962.[38] The house was destroyed by a fire in the early morning of 25 April 1962.

Destruction by fire

A fire started in the early morning of 25 April 1962. Fire engines from five stations attended, but as the swimming pool, contrary to the stipulations of the insurance policy, had been drained for cleaning and not refilled, lack of water made the fire uncontrollable. Only the blackened walls remained standing. The ruins stood for the next twenty years and were then demolished for the site of a housing development including a red-brick apartment block which now occupies the site of the former mansion.[1]

Sources

- Lost Heritage, a Memorial to the Lost Country Houses of England, website by Matthew Beckett. History and photographs c. 1930s of Lindridge.

- Chard, Judy, The Burning Buddha of Bishopsteignton, Judy Chard looks at the history of one of Devon’s oldest manors, Devon Life online, re-published in https://web.archive.org/web/20101017050929/http://www.templerfamily.co.uk/Buildings/Lindridge%20House/lindridge_house.htm. Author of "Tales of the Unexplained in Devon", in which she describes a stone statue of a Buddha, formerly the property of the Templers, from the movement of which from its accustomed place supposedly emanated a curse resulting in the fire.

- Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, 15th Edition, ed. Pirie-Gordon, H., London, 1937, p. 2217, pedigree of Templer, late of Lindridge

References

- Beckett

- Historic England. "Lindridge (1000357)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Pevsner, p.185

- Devon Record Office, archives of Comyns family of Wood, Bishopsteignton: Bargain and Sale 1039 M/T 1 1550, 1.Sir Andrew Dudley; 2. Richard Duke, London

- History of Parliament biography

- Chard, Judy

- History of Parliament biography

- Beckett; Chard, Judy

- Chard

- Christopher Hussey, writing in Country Life in 1938, thought the quality so high that he assumed that craftsmen from London had been brought down to execute the work

- Plaster decorative flora and foliage attached to the roof timbers by means of copper wire; another example at Dunsland, in north Devon was also lost to fire.(Beckett)

- Lysons, Magna Britannia, vol.6, Extinct Baronets

- Devon Record Office, archives of Comyns family of Wood, Bishopsteignton: Marriage Settlement 1039 M/F 1 20 Oct. 1732

- DRO, Assignment 1039 M/T 52 1738

- The Beauties of England and Wales, or, Delineations, topographical ..., Volume 4, by John Britton, 1803

- Lysons, Samuel & Daniel, Magna Britannia, vol.6, 1822, Devon.

- Charles Worthy. The history of the suburbs of Exeter

- Biography in History of Parliament

- Parliamentary return to John Line, Esq., high sheriff of Devon 1774 October 11

- Jane's father's name is stated as "Richard Shubrick" on Rev. John Templer's monument in Teigngrace Church. However her first husband John Line refers in his will dated 10 April 1777 to: "All monies due to me from Thomas Shubrick Esquire my wife's ffather (sic) now in America". All US sources give him as Thomas Shubrick, husband of Sarah Motte and father of Col. Thomas Shubrick (1756–1810) of Belvedere, South Carolina; However a person named Richard Shubridge did also exist, see: Smith, Henry A. M., The Baronies of South Carolina: Quenby and the EasternBranch of Cooper River, published in South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Vol. XVIII. January, 1917, No.1, p.8: "Richard and Thomas Shubrick his brother were merchants in London who came out to Carolina sometime after 1730 and were merchants in Charles Town. The earliest notice the writer has found of Richard Shubrick in South Carolina is in an unrecorded deed dated 7th June 1733 whereby "Richard Shubrick of Ratcliff "in the Parish of Stepney alias Stebunheath in the county of Middlesex, Merchant" acquired 1000 acres of land on the Edisto River about seven miles above the town called New London granted to Samuel Buttall in June 1682. From descriptions in conveyances of adjoining lands Richard Shubrick also was in possession of Quenby shortly after 1740, presumably through the right of his wife by whom he had a son named Richard Shubrick. This last Richard apparently survived bis mother and presumably inherited from her the Quenby plantation devised to her by her first husband John Ashby. Richard Shubrick seems to have returned to England with his son Richard. His brother Thomas remained in South Carolina and is the ancestor of the family of that name in South Carolina. A deed of mortgage on the record from Thomas Shubrick the son of Thomas to his cousin Richard Shubrick recites that the elder Richard Shubrick had returned to England and died there, and that his brother Thomas was indebted to him at the time of Richard's death, and to secure the debt mortgages a large amount of property including the Quinby plantation"

- As stated in will of John Line; see also The Papers of Henry Laurens: Jan. 5, 1776 – Nov. 1, 1777, page 313, Henry Laurens, David R. Chesnutt, South Carolina Historical Society, 1988

- The History of South-Carolina: From Its First Settlement in 1670, Volume 1 By David Ramsay

- Col. Thomas II Shubrick (1756–1810) served in the Revolution with the 2nd South Carolina Regiment, and was aide de camp to General Nathanael Greene. He was given the thanks of Congress for his actions at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina. See "South Carolina senate Biographies"

- Buried in Church of St Mary Arches, Exeter

- Will of John Line, Esq., proved 10/5/1777, prob 11/1031, National Archives, Kew

- "Henry Line Templer 1765-1818". Templerfamily.co.uk. 12 September 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Lysons

- Monument to Jane, wife of Rev. John Templer, in Teigngrace Church, states her date of death as 1813

- Burke's Landed Gentry, 1937, "Templer late of Lindridge", p. 2217

- Gray, Todd (Ed.), Travels in Georgian Devon: The Illustrated Journals of the Reverend John Swete, 1789-1800, 4 Vols., Vol.2, 1998, p.167

- Gray, Todd (Ed.), Travels in Georgian Devon: The Illustrated Journals of the Reverend John Swete, 1789-1800, 4 Vols., Vol.2, 1998, p.167-8

- Burke's LG

- "No. 27913". The London Gazette. 15 May 1906. p. 3326.

- Whitaker (1923), p. 178

- The Rifle Brigade (1916), p. 127

- Cokayne (1940), p. 343

- Kelly's Directory, 1939

- The brochure shows people wandering in the gardens and relaxing by the pool. The brochure also proclaimed that "The Ballroom, Morning Room, Dining Room and Main Hall have all been recently restored to suit the requirements of the House now that it is open to the Public" (quoted by Beckett)

Further reading

- Hussey, Christopher, article in Country Life Magazine, 1938

- Survey c. 1740 of capital mansion house, and barton of Lyndridge, Bartons of Hestows, Wele and Higher Humber, Manors of Bishopsteignton, Radway, advowsons of Bishopsteignton and W. Teignmouth. Devon Record Office 1039 M/E 13.

External links

- Image of 1965 oil painting "View of Lindridge, Devon", by Felix Runcie Kelly, bequeathed to National Trust by Sir Arthur Paul Benthall. National Trust collection at Benthall Hall, Broseley, Shropshire, cat. ref. 509818