Liberty Jail

Liberty Jail is a former jail in Liberty, Missouri, United States, where Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, and other associates were imprisoned from December 1, 1838, to April 6, 1839, during the 1838 Mormon War. Smith received revelations during his imprisonment there, which are now recorded as sections 121, 122, and 123 of the LDS Doctrine and Covenants, and encapsulated more fully in the Restoration Edition.[1][2]

The site at 216 North Main, two blocks northwest of the Clay County courthouse in downtown Liberty, is now owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), which operates a visitors' center featuring an indoor, cut-away reconstruction of the jail on the original site.

History

Missouri settlements

Followers of Joseph Smith from Kirtland, Ohio, were among the first settlers in the Kansas City metropolitan area, locating about 15 miles (24 km) southeast of the jail site in Independence, Jackson County, Missouri, in 1831. After Smith proclaimed that Independence was the location of the biblical Garden of Eden[3] and the City of Zion should be located there, settlers in the area feared that they would lose political control of the county to the growing numbers of immigrating Mormons. Tensions led to violence when a battle between the two groups broke out on the banks of the Blue River (Missouri). In November 1833, the Mormons were violently driven from Independence and compelled to resettle temporarily in Clay County.

In 1836, Smith's followers then moved 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Liberty to establish Far West in Caldwell County, Missouri, which had been established by the state especially for them. A few settlers led by Lyman Wight moved about 15 miles (24 km) further north to Daviess County, Missouri, where Wight established a ferry across the Grand River north of Gallatin at Adam-ondi-Ahman.

On May 18, 1838, Smith proclaimed that the land around Wight's ferry was the area to which Adam was banished after leaving the Garden of Eden, and that it would be a gathering spot prior to the Millennium. Within three months, the population of Daviess County exploded to 1,500.

Mormon War

Non-Mormon settlers in Daviess County, fearing that they would lose control of the county, attempted to prevent Mormons from voting during the Gallatin Election Day Battle on August 6, 1838. This was the first skirmish in what became known as the 1838 Mormon War, in which men would be killed and property destroyed by both sides. Increasing vigilantism on both sides led to the burning of several farms and homes, and also of the towns of Gallatin and Millport. The climax of the conflict came when Captain Samuel Bogart of the Missouri state militia took 3 Mormon men as prisoners, fearing the Mormons were going to raze Richmond and Liberty. Rumors consequently spread through Far West that a "mob" was going to execute the 3 men, and the tensions culminated in October 1838 when Mormon militia forces engaged the state militia unit on the banks of Crooked River, in what became known as the Battle of Crooked River.

Following this engagement, on October 27, 1838, Lilburn W. Boggs, governor of the state of Missouri, issued Missouri Executive Order 44: "The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace ... their outrages are beyond all description."

Smith surrenders

General Samuel D. Lucas, leading a militia of 2500 men[4] informed the Mormons at Far West that "they would massacre every man, woman and child" if Smith and several others were not given up. Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Parley P. Pratt, Lyman Wight, and George W. Robinson surrendered on November 1.[5]

A secret and illegal court martial was held following Smith's surrender. Smith and his companions were not aware of the proceeding until after it was over. At about midnight on November 1, General Lucas issued the following order to General Alexander William Doniphan: "Sir:-- You will take Joseph Smith and the other prisoners into the public square at Far West, and shoot them at 9 o-clock tomorrow morning."

General Doniphan refused to obey the order: "It is cold-blooded murder. I will not obey your order. My brigade shall march for Liberty [township] tomorrow morning at 8 o'clock; and if you execute these men, I will hold you responsible before an earthly tribunal, so help me God."[6]

General John Bullock Clark had been appointed by Governor Boggs to enforce the extermination order. He arrived and took command of the combined force on November 4. On November 5, he had an additional 56 men arrested and gave a speech in the public square at Far West. He outlined the terms of the treaty that General Lucas had previously negotiated which stripped the Mormons of all their arms and property, and required them to leave the state immediately.[7]

Preliminary hearing

On November 9, Colonel Sterling Price and a force of seventy men took Smith and his companions to Richmond, Missouri, for a preliminary hearing[8] before Austin Augustus King. The hearing began on November 13 and continued for approximately two weeks.[9]

The defense attorneys consisted of Doniphan and David Rice Atchison.

During the hearing, Smith and his companions were not permitted to call witnesses for their defense, as sometimes was allowed during such proceedings,[10] and were abused in various ways. On or about November 30, 1838, the Richmond court committed Smith and his companions, Hyrum Smith, Lyman Wight, Alexander McRae, Caleb Baldwin, and Sidney Rigdon, to Liberty Jail to await trial.[11] They were taken from Richmond to Liberty Jail in a large, heavy wagon.

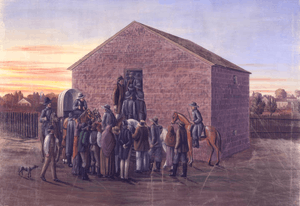

Many residents of Liberty and the surrounding area turned out to watch their arrival and some expressed their disappointment in their ordinary appearance. As the prisoners climbed the stairs and entered the jail, Smith paused on the platform at the top of the stairs, turned to face the crowd, raised his hat and said, "Good afternoon, gentlemen" before entering the jail.[12]

While Smith and his companions were incarcerated in the lower dungeon room, the upper room was used by their guards.

Change of venue and escape

On January 25, 1839, Sidney Rigdon was released from jail following an eloquent self-defence in the Clay County Courthouse. Because of threats, however, he stayed at the jail until February 5, 1839.

On April 6, 1839, Smith and the prisoners were transferred to the Daviess County Jail in Gallatin where a grand jury was investigating. The grand jury was to indict them on murder, treason, burglary, arson, larceny, theft, and stealing.[13] Smith and the followers were to appeal for a change of venue to Marion County, Missouri, in the northeast corner of the state near the village of Commerce, Illinois. However, the venue was changed to Boone County, Missouri.[14]

On April 15, 1839, en route to Boone County, Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Lyman Wight, Alexander McRae, and Caleb Baldwin were allowed to escape after the sheriff and three of their guards drank whiskey while the fourth guard helped them saddle their horses for the escape. They arrived in Quincy, Illinois, on April 22 and from there were to regroup at Nauvoo.

Smith's writings

On March 20, 1839, while incarcerated in Liberty Jail, Joseph Smith dictated a letter to Edward Partridge which was recorded by Caleb Baldwin and Alexander McRae.[15] Parts of the letter were canonized and are today known in the LDS canon as Sections 121, 122, and 123 of the Doctrine and Covenants.[16][17][18]

Doctrine and Covenants 121 begins with Smith asking God for help the difficulties being experienced by Latter Day Saints, then discusses righteous and unrighteous dominion. Doctrine and Covenants 122 talks about expectations for Smith's present and future circumstances. Doctrine and Covenants 123 instructs Latter Day Saints to document their difficulties and ask the federal government of the United States for assistance.

The Jail

Construction

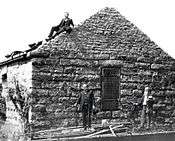

Liberty Jail was a double walled, masonry and timber structure, twenty-two and a half feet long, twenty-two feet wide, and twelve feet tall. Inside dimensions were fourteen and a half feet by fourteen feet. The building was divided into two levels, with a six and a half foot ceiling in the lower level and a seven-foot ceiling in the upper room.

The outer walls were stone masonry construction, two feet thick. The inner walls and ceilings were hewn oak logs, about a foot square. There was about a foot of space between the outside masonry walls and the inside oak walls. This space and the space above the upper ceiling were filled with loose rock to discourage escape.

The only openings in the lower level were two iron barred windows, two feet wide and six inches (152 mm) high, and an opening in the ceiling to the upper room with a heavy wooden door. The upper room had two larger iron barred windows, two feet wide by one foot tall, along with a heavy oak door. Outside the door was a small platform with a stairway down to ground level.[19]

Conditions

Smith and his companions were imprisoned in Liberty Jail for four and a half months during the coldest part of the Missouri winter.

Food was scanty, of poor quality and frequently poisoned.[20] Some of the prisoners suspected that they were sometimes fed human flesh, but comments by the guards regarding "Mormon beef" probably had reference to cattle stolen from the Mormons. Their friends on the outside were occasionally able to bring them wholesome food.

No bedding was provided, so the prisoners slept on the stone floor with only a bit of loose straw for comfort.[21]

Visitors

The prisoners were allowed visitors from time to time. Alexander McRae recorded visits by Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, George A. Smith, Don Carlos Smith, Benjamin Covey, James Sloan, Alanson Ripley, and Porter Rockwell.[22] In March, Frederick G. Williams came with Presendia H. Buell, but the jailer, concerned that tools could be passed, denied them entrance.[23]

Mary Smith visited her husband Hyrum Smith in February with their three-month-old son, Joseph F. Smith, who was named and blessed by his father in custody. Her sister, Mercy Fielding Thompson, accompanied her. Emma Smith also visited her husband Joseph multiple times with their children.[24]

Restoration

The jail was torn down although the walls of the dungeon were still visible when a house was built over it. In 1939, the property was purchased by the LDS Church and in 1963 Joseph Fielding Smith presided over the establishment of a partial reconstruction of the jail wholly within a museum. The reconstructed jail includes a front limestone facade on the east side and a cut away on the west side so visitors see the upper area and the lower dungeon which has mannequins representing Smith and the other prisoners.

References

- http://scriptures.info/scriptures/tc/section/138

- http://scriptures.info/scriptures/tc/section/139

- http://en.fairmormon.org/Joseph_Smith/Garden_of_Eden_in_Missouri

- LeSueur, Stephen C. The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri, pg. 1.

- Life of Heber C. Kimball, Whitney (1888) p. 229

- History of Caldwell County

- History of Caldwell and Livingston Counties, p. 140

- LeSueur, Stephen C. The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri, pg. 196-97

- The Refiner's Fire, Alvin R. Dyer, (1978) p. 257

- LeSueur, Stephen C. The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri, pg. 197.

- The Refiner's Fire, Alvin R. Dyer, (1978) p. 272

- The Historical Record, Andrew Jenson, ed. (1888) Vol 7 & 8 p. 667

- "Jail was Prison-Temple for Prophet". Deseret News. 1989-03-11. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- Dale R. Broadhurst's Mormon Chronology

- Joseph Smith, letter to Edward Partridge and Church members, 20 March 1839, LDS Church History Library

- Doctrine and Covenants 121

- Doctrine and Covenants 122

- Doctrine and Covenants 123

- The Historical Record, Andrew Jenson, ed. (1888) Vol 7 & 8 p. 670

- "Liberty Jail - The Encyclopedia of Mormonism". eom.byu.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- The Refiner's Fire, Alvin R. Dyer, (1978) p. 281-282

- History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Period 1 (1948) Vol. III, p 257

- Williams, Frederick G., The Life of Dr. Frederick G. Williams: Counselor to the Prophet Joseph Smith (BYU Studies 2012) pp. 564-65; Cottle, Thomas D. and Patricia C., Liberty Jail and the Legacy of Joseph (1998) pp. 204-205.

- The Refiner's Fire, Alvin R. Dyer (1978) p 289

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liberty Jail. |