Lead climbing

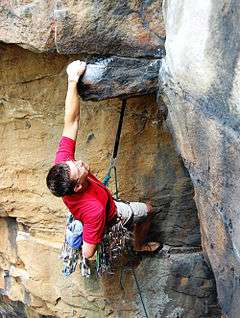

Lead climbing is a climbing style, predominantly used in rock climbing.[1][2] In a roped party one climber has to take the lead while the other climbers follow.[3][4] The lead climber wears a harness attached to a climbing rope, which in turn is connected to the other climbers below the lead climber. While ascending the route, the lead climber periodically connects the rope to protection equipment for safety in the event of a fall. This protection can consist of permanent bolts, to which the climber clips quickdraws, or removable protection such as nuts and cams. One of the climbers below the lead climber acts as a belayer. The belayer gives out rope while the lead climber ascends and also stops the rope when the lead climber falls or wants to rest.[5][6]

| Part of a series on |

| Climbing |

|---|

Lead climbing route at the Climbing World Championships 2018 |

| Background |

| Types |

| Lists |

| Terms |

| Gear |

A different style than lead climbing is top-roping. Here the rope is preattached to an anchor at the top of a climbing route before the climber starts their ascent.[1] Lead climbing as a discipline of sport climbing would have debuted at the 2020 Summer Olympics.[7]

Basics and safety

Lead climbing is done for several reasons. Often, placing a top-rope is not an option because the anchors are not accessible by any means other than climbing. Sport climbing and traditional climbing both utilize lead climbing techniques for practical reasons, as well as stylistic reasons.

When lead climbing, the lead climber or leader wears a harness attached to one end of a climbing rope with a tie-in knot, like figure-eight, or bowline on a bight.[8][9][10] This rope is usually a dynamic kernmantle rope which is both resistant to abrasion and also softens the impact of a fall by stretching to some degree.[11][12] The leader's partner or follower provides the belay, paying out rope as needed, but ready to hold the rope tightly, usually with the aid of a belay device, to catch the leader in the event of a fall.[5][6]

Protection

The lead climber ascends the route, periodically placing protection for safety in the event of a fall. The used protection differs based on the climbing discipline.[13]

In traditional climbing ("trad") the protection is usually only temporarily attached to the wall. Nuts and spring-loaded camming devices are placed in cracks of the rock face, slings can be tied around rock spikes and hooks can be placed on small ledges. These devices usually have a carabiner attached to one end, which allows the climber to clip in the rope. These devices are later collected again, usually by the followers when they ascend themselves.

In sport climbing there is usually only one climber. The climbing partner remains on the ground and belays the lead climber while they ascend the sport route. In sport climbing protections are usually permanently attached to the rock face in the form of drilled bolts or chains which are used for attaching quickdraws directly. The quickdraws are either placed by the lead climber during the ascent or are placed beforehand.

Fall distance and impact

Distances between pieces of protection can range from three to forty feet or more, although most often the distance is between six and twelve feet.

At any point, protection will be placed so that the distance to the most recently placed protection will be at most, half of the length of a possible fall. For example, if a leader is ten feet above the last piece of protection, any fall should be a maximum of twenty feet. Realistically, the fall would likely include several more feet due to rope elasticity and slack and give in the overall mechanical system.[14] If a lead climber, starting from the ground, approaches twice the height of the last piece of protection, there is danger of a ground fall (more commonly referred to as "decking") in which the falling climber hits the ground before the rope goes tight.

The severity of a fall arrested by the climbing rope is measured by the fall factor: the ratio of the height a climber falls before their rope begins to stretch and the rope length available to absorb the energy of the fall. (A leader may reduce their fall factor by using "protection", equipment that attaches in some way to the rock, allowing the rope to pass through it.) As the rope begins to stretch, it absorbs the energy of the fall and slows the falling climber. The more the rope is stretched by the force of the faller, the more intense the force it exerts on the faller, and the more severe any effect of that force. For this reason, a fall of 20 feet is much more severe (exerts more force on the climber and climbing equipment) if it occurs with 10 feet of rope out (i.e. the climber has placed no protection and falls from 10 feet above the belayer to 10 feet below—a factor 2 fall) than if it occurs 100 feet above the belayer (a fall factor of 0.2), in which case the stretch of the rope more effectively cushions the fall.

Risks

Several poor practices during lead climbing can lead to severe risk.

- Back-clipping can result in protection getting unclipped by the rope during a fall. It often occurs when the climber does not grip the rope correctly during clipping. A carabiner is back-clipped when the rope coming from the climber goes through the back of the carabiner before coming out of the front of the carabiner and then down to the belayer. To avoid back-clipping the climber should always make sure that the rope coming from their harness goes through the front of the carabiner towards the face of the wall and then down to the belayer.[15][16][17]

- Z-clipping occurs when the climber grabs the rope behind an already clipped quickdraw and clips it into the next quickdraw. This results in a zig-zag shape of the rope on the wall, which can create immense friction, making further ascending hard to impossible until it is fixed. It also gives the illusion of being clipped into a higher protection, even though the climber would actually fall to a lower protection before being caught by the rope. To avoid Z-clipping always grab the rope right below the tie-in knot before pulling it upwards towards the next quickdraw. [16][17]

- Turtling can occur when one of the climber's limbs is behind the rope and the climber falls off the wall. The climber is flipped upside down, like a turtle on its back. Sometimes this can eject the climber from the harness.[16][17]

In traditional climbing, failure to place removable protection adequately may also result in lost protection.[18]

Multi-pitch climbing

Long routes, for instance in big wall climbing, are usually climbed in multiple pitches. One climber takes the lead and the other climbers wait at a spot where they can anchor themselves securely and are not in risk of falling. The lead climber is belayed until the end of the rope is reached or a convenient place for a new anchor is found. Here the lead climber secures themself to a new anchor and waits while the other climbers follow. Often the lead climber gives belay to the followers at this point. When the other climbers reach the new anchor the process is repeated. Usually another climber takes the lead for the new pitch and the previous leader can rest.[19]

In mountaineering it is also common that the other climbers do not wait for the lead climber to reach the end of a pitch. They already start climbing beforehand. This practice increases the risk of the entire rope party falling to their deaths or serious injury should the protections placed between the lead climber and the followers fail. On the other hand it shortens the length of time necessary for completing a section, which in turn lowers the risk of getting caught in an avalanche, bad weather or getting hit by falling ice or rock. This practice is known as simul-climbing.[20][21]

Competition

.jpg)

Lead climbing is a popular discipline in competition climbing together with bouldering and speed climbing. The setup usually mirrors the outdoor sport climbing variant.[22] An artificial climbing wall is prepared with a complex route made up of geometry and climbing holds. Bolts with preattached quickdraws serve as protection. The competitors are expected to free climb, in other words they cannot use the protection to make progress or hang in the rope to rest.

Performance is determined by the highest hold reached and whether or not that hold was "controlled", meaning the climber achieved a stable position on that hold, or "used", meaning the climber used the hold to make a controlled climbing movement in the interest of progressing along the route.[23]

Lead competitions usually consist of three rounds: qualifications, semifinals, and finals.[24]

As a discipline of sport climbing it will debut at the 2020 Summer Olympics.[25] It has also been confirmed to be part of the Paris 2024 Summer Olympics.[26]

See also

- Rock climbing

- Climbing equipment

- Sport climbing

- Glossary of climbing terms

- Traditional climbing

References

- "Learn: Styles of Rock Climbing". mojagear.com. Archived from the original on Jul 22, 2017.

- "Rock Climbing Terms: Styles and Techniques". American Alpine Institute. Archived from the original on Feb 4, 2019.

- "Trad Skills: Changing Leaders in a Party of Three". climbing.com. Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.

- "Alpine climbing knowledge". Ortovox. Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.

- "How to Belay". Rock and Ice. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018.

- "How to Belay". rei.com. Archived from the original on Jul 1, 2019.

- "Vertical Triathlon: The Future of Climbing in the Olympics". climbing.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019.

- "Duell der Knoten: Achter versus Bulin (Duel of the knots: Figure-eight vs. Bowline)". Klettern.de. Archived from the original on Jun 22, 2019.

Der gesteckte Achterknoten und der doppelte Bulin erfüllen diese Anforderungen. Es sind deshalb auch die beiden Einbindeknoten, die der Deutsche Alpenverein bei seinen Kursen lehrt, wobei der Achterknoten bei Einsteigern den Vorzug erhält, weil er sich leichter kontrollieren lässt.

- "Know-How Am Berg - Wesentliches zu Ausrüstung, Planung und Seiltechnik (engl: Know-how on the mountain - Essentials of equipment, planning and rope handling" (PDF). DAV. Archived from the original (PDF) on Jun 24, 2019.

Der Achterknoten, in diesem Fall als „gesteckter Achter“ oder als „doppelter Bulin“ ausgeführt, dient als Anseilknoten.

- "So binden Sie sich richtig ein und so bitte nicht! (This is how you tie yourself in properly and this is how you don't do it!)". Alpin. Archived from the original on Oct 13, 2018.

- "The Ultimate Guide to Climbing Ropes". theclimbingguy.com. Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.

- "A Theoretically Perfect Climbing Rope". climbing.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2017.

- "Trad Climbing Basics". rei.com. Archived from the original on Apr 27, 2019.

- "The Noob's Guide to Rock Climbing". Outside Online. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019.

- "Back Clipping vs. Proper Clipping Technique". Sierra. Archived from the original on Jul 7, 2019.

- "Sport Climbing – Lead Skills". Archived from the original on Oct 18, 2018.

- "Three Common Lead Climbing Mistakes to avoid". Gripped magazine. Archived from the original on Jul 7, 2019.

- "How to Place Protection". Rock and Ice. Archived from the original on Jul 7, 2019.

- "Multi-pitch Climbing 101: The Complete Guide". 99boulders.com. Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.

- "Advanced Techniques: Simul-Climbing and Short-Fixing". climbing.com. Archived from the original on Apr 29, 2019.

- Jason D. Martin, Alex Krawarik. Washington Ice: A Climbing Guide. Mountaineers Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-0898869460.

- "About Climbing". Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.

- "A Guide to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Climbing Format". climbing.com. Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.

- "A guide to... competition climbing". tiso.com.

- "Vertical Triathlon: The Future of Climbing in the Olympics". climbing.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019.

- "Olympic Committee Unanimously Votes to Include Sport Climbing in Paris 2024 Games". climbing.com. Archived from the original on Jul 4, 2019.