Belaying

Belaying refers to a variety of techniques climbers use to exert tension on a climbing rope so that a falling climber does not fall very far.[1] A climbing partner typically applies tension at the other end of the rope whenever the climber is not moving, and removes the tension from the rope whenever the climber needs more rope to continue climbing.

| Part of a series on |

| Climbing |

|---|

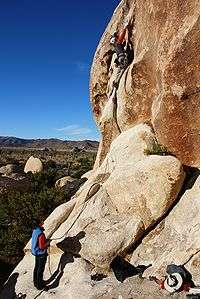

A belayer in Red Rocks, Nevada |

| Background |

| Types |

| Lists |

| Terms |

| Gear |

The term "belay" also means the place where the belayer is anchored; this is typically a ledge, but may be a hanging belay, where the belayer themself is suspended from a projection in the rock.

How it works

In a typical climbing situation, one end of the rope is fixed to the harness of the climber, using either a Double Figure Eight, bowline, or double bowline knot. The rope then passes through climbing protection, which is fixed into the rock. Attachment to the rocks may be via bolts that are permanently fixed into the rock, or by traditional protection that the climber places and later removes without altering the rock.

The rope runs through the protection to a second person called the belayer. The belayer wears a harness to which they have attached a belay device. The rope threads through the belay device. By altering the position of the end of the rope, the belayer can vary the amount of friction on the rope. In one position, the rope runs freely through the belay device. In another position, it can easily be held without moving, because the friction on the rope is so great. This is called 'locking off' the rope.

If the climber climbs three feet higher than the last piece of protection in the rock, and then falls, the rope allows him to fall the three feet to the protection, and another three feet below that. If they fall any further, rope is pulled upwards through the protection from the belayer below. Because the belayer generally keeps the rope locked off, the climber's fall should be arrested and they are left suspended, but safe, somewhere below the protection.

A dynamic rope, which has some stretch in it, is often used so that the climber is not brought to a sudden jarring stop. Some climbers choose static ropes for abseiling/rapelling because it's easier to use.

As the climber continues to ascend, they clip the rope into higher and higher metal loops fixed into the rock, so that in the event of a fall they don't fall further than the "unclipped" length of rope allows. While the task of belaying is typically assigned to a companion who stays at the bottom, self-belaying is also possible as an advanced technical climbing technique.

The person climbing is said to be on belay when one of these belaying methods is used. Belaying is a critical part of the climbing system. A correct belaying method lets the belayer hold the entire weight of the climber with relatively little force, and easily arrest even a long fall. By using a mixture of belaying angle and hand-grip on the rope, the belayer can gently lower a climber to a safe point where climbing can be resumed.

Belayer responsibilities

The belayer should keep the rope locked off in the belay device whenever the climber is not moving. As the climber moves on the climb, the belayer must make sure that the climber has the right amount of rope by paying out or pulling in excess rope. If the climber falls, they free-fall the distance of the slack or unprotected rope before the friction applied by the belayer starts to slow their descent. Too much slack on the rope increases the distance of a possible fall, but too little slack on the rope may prevent the climber from moving up the rock. It is important for the belayer to closely monitor the climber's situation, as the belayer's role is crucial to the climber's safety.

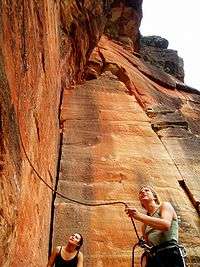

When belaying on overhanging bolted routes, particularly indoors, belayers often stand well back from the rock so that they can watch the climber more easily. However, when belaying a lead climber who is using traditional protection, this can be very dangerous. The belayer should stand near to the bottom of the route in order to decrease the angle of the rope through the first piece of protection. This, in turn, decreases the force pulling it up and out of the rock if the leader falls. Standing too far away from the rock can result in protection unzipping, with the lowest piece being pulled away from the rock, followed by the next, until all of the protection may potentially be pulled out.[2] Standing too far away from the bottom of the climb also means that if the leader falls, the belayer experiences a sudden pull inwards towards the rock and may be pulled off their feet or into the rock.

Communication

Communication is also extremely important in belaying. Climbers should wait for a verbal confirmation from the belayer that they are ready to begin.

US terminology

In the US, usually the climber asks, "On belay?" or "Belay?" and wait for the belayer to reply "Belay on." Once ready, the climber follows with a "Climb ready" or "Climbing". The belayer usually acknowledges this by calling, "Climb on."

During the climb, the climber may ask the belayer for "Slack," "Tension," warn of a "Rock!," or that they are about to be "Falling!." At the top of the climb, the climber may elect to climb back down, be lowered down, walk back down, set up a new belay point for another pitch, or set up a new line to rappel down from. The choice must be made clear to the belayer. When the climber is in a safe position independent of the belay they call "Off belay."

At times, it may be impossible for climbing partners to hear one another, for example, in bad weather, by the sea, or near a busy road. Silent belay communication is possible via tugging the rope. Some people use walkie talkies in areas where communication is limited.

UK terminology

When the climber is tied onto the rope and is ready to climb "Ready to climb"

When the belayer has attached the rope to the belay device, and is ready to belay "Climb when ready" (or in recent years "On belay" or "Belay ready")

When the climber is about to start climbing "Climbing"

When the belayer is belaying "OK"

When the slack rope is taken in by the belayer and it becomes tight and therefore the belayer doesn't need to take the rope in any more the climber says "That's me"

During the climb, the climber may ask the belayer for "Slack", or to take in the rope "Take In" (NB: The command "Take in slack" is NEVER used as it's confusing)

If the climber is about to fall and they need the belayer to know & take in the rope, they may say "Tight" for a tight rope or "Take In" to take the rope in.

When the climber is in a safe position independent of the belay "Safe" or "I'm safe".

When the belayer has taken the climber off belay "Off belay"

Warning SHOUTS for falling objects "Below!", when throwing a rope off the edge "Rope Below!", when a rock has been dislodged and is falling "Rock below!"[3]

Anchoring

When top rope belaying for a significantly heavier partner, it is sometimes recommended that the belayer anchor themselves to the ground. The anchor point does not prevent a fall, but prevents the belayer from being pulled upwards during a fall.[4] This is normally not used when lead belaying.[5]

To set up this anchor the belayer should place a piece of directional protection (i.e., a nut or cam) into a crack below their body, or tie themselves by the belay loop to a rock or tree. The anchor arrests any upward force produced during a fall thus preventing the belayer from "taking off". Unlike belays set up at the top of a climb, it is not usually necessary for belayers at the bottom to have more than one point of protection as long as the single piece is sturdy and safe – "bomber" in climber jargon.

Hanging belay

During multipitch climbs it is sometimes necessary to belay while sitting in a harness and anchored to the wall. In this case rope management becomes more important, and the anchor is constructed in the traditional manner.[6]

Belay methods

Climbers now almost exclusively use a belay device to achieve controllable rope friction. Before the invention of these devices, climbers used other belay methods, which are still useful in emergencies.

Belay devices

A belay device is a piece of climbing equipment that improves belay safety for the climber by allowing the belayer to manage his or her duties with minimal physical effort. Belay devices are designed to allow a weak person to easily arrest a climber's fall with maximum control, while avoiding twisting, heating or severely bending the rope.

Munter hitch / Italian hitch

A munter hitch is a belaying method that creates a friction brake by tying a special knot around an appropriate carabiner. This type of belay, however, causes the rope to become twisted. It can also be used on double ropes. Simply tie the munter hitch with both ropes as if they were one.

Body belay

Before the invention of belay devices, belayers could add friction to the rope by wrapping it around their body; friction between rope and the belayer's body was used to arrest a fall. This is known as a body belay, a hip belay, or a waist belay and is still sometimes used when climbing quickly over easier ground. On vertical rock it is no longer used as it is less reliable and more apt to injure the belayer stopping a long fall.[7]

Australian belay

The Australian belay is used on many high ropes courses for supporting participants on vertical, as opposed to traversing, elements.[8] The Australian belay allows untrained participants to engage in the safety and support of their fellow participants on an element, and allows a single facilitator to oversee an element with multiple individuals participating. The Australian belay does not use a traditional belay device, but rather ties two or more people into loops on the working end of the rope as a belay team, who walk backward as the participant ascends the element, taking up slack as they go. Additional participants can be tied into the loops or left free to help hold clipped in members of the belay team in place. The Australian belay requires a clear runway back from the element almost double the height of the element in order to allow the belay team to support climbers all the way to the top.

References

- A Glossary of Climbing Terms

- Staying Alive: Some tips for Single Pitch Climbing

- "How to use climbing calls". The BMC TV. Archived from the original on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- Dave Sheldon (15 June 2012). "Learn This: Belaying A Heavier Climber". Climbing.com.

- Kitty Calhoun (27 October 2016). "Belaying an XL – Tips for Lightweight Climbers". Rock and Ice.

- "How to Maximize Comfort at Hanging Belays". Climbing.com. 24 March 2016.

- "How to Hip Belay". Climbing.com. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "About the Australian Belay". Project Adventure. Retrieved 2 April 2016.