Laurence Duggan

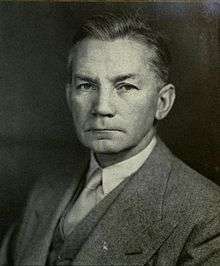

Laurence Duggan (1905–1948), also known as Larry Duggan, was a 20th-century American economist who headed the South American desk at the United States Department of State during World War II, best known for falling to his death from the window of his office in New York, shortly before Christmas 1948 and ten days after questioning by the FBI about whether he had had contacts with Soviet intelligence.[1][2]

Laurence Duggan | |

|---|---|

| Born | Laurence Hayden Duggan May 28, 1905 |

| Died | December 20, 1948 |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Boyd |

| Institution | Institute of International Education |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

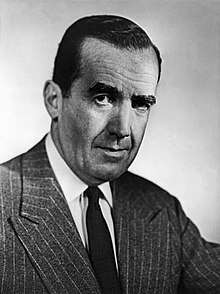

Despite public accusations by Whittaker Chambers and others, Duggan's loyalty was attested to by such prominent people as Attorney General Tom C. Clark, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Duggan's close associate journalist Edward R. Murrow, among others.[3] However, in the 1990s, evidence from decrypted Soviet telegrams revealed that he was an active Soviet spy for the KGB in the 1930s and 1940s.[4]

Background

Laurence Hayden Duggan was born on May 28, 1905, in New York City. His father, Stephen P. Duggan, was a professor of Political Science at the City College of New York before founding the Institute of International Education. His mother Sarah Alice Elsesser was a director of the "Negro Welfare League" of White Plains, New York.[1]

Duggan received early education at the Roger Ascham School in Hartsdale, New York, and White Plains Community Church, where he learned simplicity, courtesy, and democracy. In 1923, he graduate cum laude from the Phillips Exeter Academy. In 1927, he graduated with distinction from Harvard University.[1] (Ware Group members such as Alger Hiss and Lee Pressman were 1929 graduates of Harvard Law School.) In 1930, when he joined State, he took postgraduate courses in history, government, and economics at the George Washington University.[1]

Career

In 1927, Duggan began his career by working for Harper Brothers publishers. By 1929, his father, then director of the Institute of International Education, created a bureau for Latin America and offered the position to his son. Duggan accepted, learned Spanish and Portuguese, and toured the region to become better acquainted with it. By 1930, he had produced a report that reached Charles Howland, head of studies in international relations at Yale University. Howland forwarded the report to Dana Munro, chief of the Latin American Division, who offered Duggan a position.[1]

Civil service

In 1930, Duggan moved to Washington, DC, to join the U.S. Department of State—nine of those years as head of the Latin American Division and four as adviser on political relations. (His Harvard friend Noel Field had joined State in the late 1920s.) Duggan served as Secretary of State Cordell Hull's at major conference in Lima, Peru and Havana, Cuba. Positions he held included Chief of the Division of the American Republics as well as Political Adviser and Director of the Office of the American Republics.[1]

In 1944, Duggan returned briefly to the private sector, when he served as consultant on Latin American affairs–a "profitable business."[1]

Shortly thereafter, Herbert H. Lehman (New York governor) and Dr. Eduardo Santos (former president of Colombia, asked Duggan to serve the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) for six months. (In 1936, his friend Noel Field had taken a position for the U.S. with the League of Nations and then in 1941 become director of the American Unitarian Universalist Service Committee's relief mission in Marseilles.)[1]

Institute of International Education

In 1946, a committee of the IIE (comprising Virginia Gildersleeve of Barnard College, Edward R. Murrow of CBS News, Waldo Leland of the Carnegie Institute, and Arthur W. Packard of Rockefeller Brothers Fund) offered Duggan the presidency of the Institute of International Education (IIE) upon his father's retirement. The IIE provided for a flow of exchange students between the United States and several other countries.[1]

On November 1, 1946, Duggan began as IIE president. One of his first actions was to make the board more inclusive by adding women, union representatives ("labor men"), and African-Americans including Benjamin Mays of Morehouse College (a mentor of Martin Luther King, Jr.). He expanded students to include trainees, entrepreneurs, labor leaders, professionals, artists, and musicians. U.S. President Truman appointed Duggan to the ten-member administrators of the Fulbright Act. He provided advice during the establishment of UNESCO. In 1947, he served as a member of the U.S. delegation to the second session of the UNESCO general conference, held in Mexico City.[1][2]

During his two years as president, IIE's funding increased its budget nearly 400% from $109,000 to $430,000. Funding from the Carnegie Corporation alone increased $50,000 per year during that time (and Alger Hiss became president of sister organization, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace within days of Duggan's appointment to the IIE).[1]

Espionage

Duggan was a close friend of Noel Field of the State Department. The GRU had also tried to recruit him through Frederick Field.[5]

In the mid-1930s, Duggan was recruited by Hede Massing as a Soviet spy.[6] Duggan told the FBI that Henry Collins of the Ware group had also tried unsuccessfully to recruit him to the NKVD.[5] [7]

Peter Gutzeit, the Soviet Consul in New York City, was also an officer in the NKVD. In 1934 he identified Laurence Duggan as a potential recruit. Boris Bazarov told Hede Massing that they wanted her to help recruit Duggan and Noel Field. The plan, suggested by Gutzeit, was to use Duggan to draw Field into the network.[8] Gutzeit wrote on 3 October 1934, that Duggan "is interesting us because through him one will be able to find a way toward Noel Field... of the State Department's European Department with whom Duggan is friendly." [9]

Duggan provided Soviet intelligence with confidential diplomatic cables, including from American Ambassador William Bullitt. He was a source for the Soviets until he resigned from the State Department in 1944.[10]

According to Whittaker Chambers in his 1952 memoir, Egmont Gaines proposed covert group, "insisting" the group approach Duggan, "whom he called 'very sympathetic'."[11] Duggan was then in the State Department, and became chief of its Latin-American Division.[11] According to Boris Bazarov, Duggan told his Soviet handlers, he only remained "at his hateful job in the State Department" because he was "useful for our cause."[12]

Personal and death

In 1932, Duggan married Helen Boyd, a Vassar College graduate. They had four children: Stephanie, Laurence Jr., Robert, and Christoper.[1]

December 20, 1948

On December 20, 1948, Duggan fell to his death from his office at the Institute of International Education, located on the 16th floor of a building in midtown Manhattan.[2] His body was discovered around 7:00 PM that evening.[1] A few days later, the New York Police Department made public the result of its investigation, which concluded: "Mr. Duggan either accidentally fell or jumped."[2]

During his last four days, he spoke with his father about funding for the IIE, his mother about Christmas, with Dr. Santos at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel about US-Latin American relations, and on December 20 itself with Pierre Bédard, director of the French Institute, about inviting a distinguished French national to lecture in the United States under IIE auspices.[1]

Remembrances

Friends published a memorial book about Duggan, with contributions made directly to the book or gleaned from the press by: Eleanor Roosevelt, Tom C. Clark, Sumner Welles, Marquis Childs (friend), Edward R. Murrow, Roscoe Drummond, and Raymond Moley, Joseph Harsh, Elmer Davis, Martin Agronsky, Henry R. Luce, Clarence Pickett, and Harry Emerson Fosdick. Archibald MacLeish composed a memorial poem, published in the New York Herald Tribune[1]

On December 21, 1948, at 7:45 PM (barely 24 hours after Duggan's death), Murrow broadcast on CBS radio:

Tonight, the headlines are shouting: "Duggan Named in Spy Case." Who named him? Isaac Don Levine, who said he was quoting Whittaker Chambers. And who denies it? Whittaker Chambers. Tonight, Representative Mundt says: "The Duggan affair is a close book so far as the House Committee is concerned." The Representative from South Dakota also says he is thinking of making recommendations for changing the procedure at committee hearings, maybe even giving the accused person the right to be heard before the Committee issues a report.

The members of the Committee who have done this thing upon such slight and wholly discredited testimony may now consult their actions and their consciences.[1]

Deaths of W. Marvin Smith and others

On October 20, 1948, W. Marvin Smith, a U.S. Department of Justice attorney and notary with whom Alger Hiss had worked, was found dead in the southwest stairwell of the (then) seven-story Justice building.[13][14] Just after Laurence Duggan's death, the Associated Press reported:

The widow of W. Marvin Smith, a justice department employee who died in a five story plunge 2 months ago, expressed belief today that his death was simply an accident.

She told a reporter she feels certain it was not a suicide and was not connected in any way with his appearance as a minor witness in congressional hearings. Smith's death had been recalled in some newspaper accounts of the death of Laurence Duggan in New York City.

On Oct. 20, Smith hurtled to his death down circular stairwell in the justice department. That was also the opinion of justice officials.

Smith, 53, was an attorney in the solicitor general's office. Last summer, he figured in a minor way in the house committee on un-American activities.[15]

In 1951, the Chicago Tribune newspaper speculated about "several suicides and mysterious deaths"[16] among spies and government officials mostly related to the Hiss Case, including:

- Nov 1947: John Gilbert Winant (suicide). US ambassador to England, following personal depression

- Aug 1948: Harry Dexter White (heart attack)

- Oct 1948: W. Marvin Smith (suicide)

- Dec 1948: Laurence Duggan (suicide). Regarding Duggan, like Hiss a former State Department official, the newspaper commented, "There was speculation that he might have fallen accidentally or that he might have been thrown from the window, but it was widely believe he committed suicide." (Duggan fell sixteen stories with one snow boot on.)

- May 1949: James Forrestal (suicide), first US Secretary of Defense

- 1949, Morton Kent, another State Department official, committed suicide after his implication in the trial of Judith Coplon

- Feb 1950: Laird Shields Goldsborough (suicide). Goldsborough was a senior editor at Fortune and TIME magazines and former boss of Whittaker Chambers: he fell out of a ninth-floor building – and left his estate to the Soviet government.

- Apr 1950: Francis Otto Matthiessen (suicide). The Harvard professor jumped from the 12 floor of his Boston hotel, according to his sister because of proceedings in the trial of Harry Bridges (defended by Carol Weiss King, who also defended J. Peters, head of the Ware Group).

- Nov 1952: Abraham Feller (suicide). The UN legal counsel (and friend of Alger Hiss) jumped out his window when Adlai Stevenson Jr. lost the 1952 presidential elections, UN Secretary General Trygve Lie resigned, and a US grand jury and the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee continued investigations into Americans working at the UN.

Venona

The Venona project succeeded in decrypting some Soviet intelligence cables that had been intercepted in the mid-1940s. The code name used for Laurence Duggan in the decrypted transcripts is "Frank"[5] and "19".[17][18] He is referenced in the following Venona decryptions, which provided information to the Soviets about Anglo-American plans for invading Italy during World War II:

- 1025, 1035–1936, KGB New York to Moscow, June 30, 1943

- 380 KGB New York to Moscow, March 20, 1944

- 744, 746 KGB New York to Moscow, May 24, 1944

- 916 KGB New York to Moscow, June 17, 1944

- 1015 KGB New York to Moscow, to Victor [Fitin], July 22, 1944

- 1114 KGB New York to Moscow, August 4, 1944

- 1251 KGB New York to Moscow, September 2, 1944[19]

- 1613 KGB New York to Moscow, November 18, 1944

- 1636 KGB New York to Moscow, November 21, 1944

See also

References

- Welles, Benjamin Sumner (1949). Laurence Duggan 1905–1948: In Memoriam. Overbrook Press. pp. 3 (family, education), 4 (marriage, children), 4–5 (State), 5–6 (UNRRA), 6–8 (IIE), 8 (1948), 11 (body), 41–44 (Murrow broadcast), 90 (UNRRA). Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "The Man in the Window". Time. 3 January 1949. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- John Earl Haynes; Harvey Klehr (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale UnP. p. 202. ISBN 0300129874.

- Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America - The Stalin Era (2000) pp 3-21.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (1999). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. pp. 201–204.

- Massing, Hede (1951). This Deception: KBG Targets America. Duell, Sloan and Pearce. pp. 176, 207–209. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America - The Stalin Era (2000) pp 3-21.

- http://spartacus-educational.com/Laurence_Duggan.htm

- Peter Gutzeit, Soviet Consulate in New York City, memorandum to Moscow (3rd October, 1934)

- Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America - The Stalin Era (2000) pp 3-21.

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 339.

- Julian Borger, "The Spy Who Made McCarthy: New Evidence Reveals that the Unwitting Architect of the McCarthy Witch-Hunts was a Soviet Agent," The Guardian, 26 January 1999.

- "Clark Counsel Falls to Death". Los Angeles Times. 21 October 1948. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Clark Counsel Falls to Death". Salt Lake Tribune. 21 October 1948. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Widow of U.S. Aid Lined to Spy Quix Calls Death Accident". Chicago Tribune. 23 December 1948. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Suicide Trail Winds Thru Spy, Crimes Exposes: Kefauver Probe Recalls Reles Death Mystery". Chicago Tribune. 1 April 1951. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr: Was Harry Hopkins A Soviet Spy?

- Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev. The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America - The Stalin Era (2000) pp 3-21.

- National Security Agency Venona transcript, September 2, 1944

Sources

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (16 August 2013). "Was Harry Hopkins a Soviet Spy?". Frontpage. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Haynes, John Earl; Harvey Klehr (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale UnP. p. 202. ISBN 0300129874.

- Massing, Hede (1951). This Deception: KBG Targets America. Duell, Sloan and Pearce. pp. 176, 207–209. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Vassiliev, Alexander (2003). "Notes on Anatoly Gorsky's December 1948 Memo on Compromised American Sources and Networks". Wilson Center. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Welles, Benjamin Sumner (1949). Laurence Duggan 1905–1948: In Memoriam. Stamford, CT: Overbrook Press.