Larix occidentalis

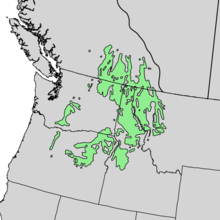

Larix occidentalis, the western larch, is a species of larch native to the mountains of western North America (Pacific Northwest, Inland Northwest); in Canada in southeastern British Columbia and southwestern Alberta, and in the United States in eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, northern Idaho, and western Montana.

| Western larch | |

|---|---|

| William O. Douglas Wilderness | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Larix |

| Species: | L. occidentalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Larix occidentalis | |

| |

| Natural range of Larix occidentalis | |

Description

It is a large deciduous coniferous tree reaching 30 to 60 metres (98 to 197 feet) tall, with a trunk up to 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) diameter. The largest known western larch is 47 m (153 ft) tall and 6.7 m (22 ft) in circumference with a 10 m (34 ft) crown, located at Seeley Lake, Montana. The crown is narrow conic; the main branches are level to upswept, with the side branches often drooping. The shoots are dimorphic, with growth divided into long shoots (typically 10 to 50 cm (4 to 20 in) long) and bearing several buds, and short shoots only 1 to 2 mm (1⁄32 to 3⁄32 in) long with only a single bud. The leaves are needle-like, light green, 2 to 5 cm (3⁄4 to 2 in) long, and very slender; they turn bright yellow in the fall, leaving the pale orange-brown shoots bare until the next spring.

The seed cones are ovoid-cylindric, 2 to 5 cm (3⁄4 to 2 in) long, with 40 to 80 seed scales; each scale bearing an exserted 4 to 8 mm (3⁄16 to 5⁄16 in) bract. The cones are reddish purple when immature, turning brown and the scales opening flat or reflexed to release the seeds when mature, four to six months after pollination. The old cones commonly remain on the tree for many years, turning dull gray-black.

It grows at elevations between 500 and 2,400 m (1,600 and 7,900 ft), and is very cold tolerant, able to survive winter temperatures down to about −50 °C (−58 °F). It only grows on well-drained soils, unable to thrive on waterlogged ground.

The seeds are an important food for some birds, notably pine siskin, redpoll, and Two-barred crossbill.

In autumn, the foliage frequently turns yellow before it falls off.

Uses

Some Plateau Indian tribes drank an infusion from the young shoots to treat tuberculosis and laryngitis.[2]

The wood is tough and durable, but also flexible in thin strips, and is particularly valued for yacht building; wood used for this must be free of knots, and can only be obtained from old trees that were pruned when young to remove side branches. Small larch poles are widely used for rustic fencing.

Western larch is used for the production of Venice turpentine.

The wood is highly prized as firewood in the Pacific Northwest where it is often called "tamarack," although it is a different species than the tamarack larch. The wood burns with a sweet fragrance and a distinctive popping noise.

Indigenous peoples used to chew gum produced from the tree as well as eat the cambium and sap.[3]

The sweetish galactan of the sap can be made into baking powder and medicine. Grouse browse the tree's leaves and buds.[4]

References

![]()

- Farjon, A. (2013). "Larix occidentalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42315A2971858. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42315A2971858.en.

- Hunn, Eugene S. (1990). Nch'i-Wana, "The Big River": Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. University of Washington Press. p. 354. ISBN 0-295-97119-3.

- Turner, Nancy J. Food Plants of Interior First Peoples (Victoria: UBC Press, 1997) ISBN 0-7748-0606-0

- Whitney, Stephen (1985). Western Forests (The Audubon Society Nature Guides). New York: Knopf. p. 363. ISBN 0-394-73127-1.