Lamu

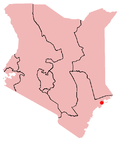

Lamu or Lamu Town is a small town on Lamu Island, which in turn is a part of the Lamu Archipelago in Kenya. Situated 341 kilometres (212 mi) by road northeast of Mombasa that ends at Mokowe Jetty, from where the sea channel has to be crossed to reach Lamu Island. It is the headquarters of Lamu County and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Lamu | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| |

Lamu Location in Kenya | |

| Coordinates: 2°16′10″S 40°54′8″E | |

| Country | |

| County | Lamu County |

| Founded | 1370 |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 25,385 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Official name | Lamu Old Town |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iv), (vi) |

| Reference | 1055 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th session) |

| Area | 15.6 ha (39 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 1,200 ha (3,000 acres) |

The town contains the Lamu Fort on the seafront, constructed under Fumo Madi ibn Abi Bakr, the sultan of Pate, and was completed after his death in the early 1820s. Lamu is also home to 23 mosques, including the Riyadha Mosque, built in 1900, and a donkey sanctuary.

History

Early history

The original name of the town is Amu,[2] which the Arabs termed Al-Amu (آامو) and the Portuguese "Lamon". The Portuguese applied the name to the entire island as Amu was the chief settlement.

Lamu Town on Lamu Island is Kenya's oldest continually inhabited town, and was one of the original Swahili settlements along coastal East Africa. It is believed to have been established in 1370.[3]

Today, the majority of Lamu's population is Muslim.[4]

The town was first attested in writing by an Arab traveller Abu-al-Mahasini, who met a judge from Lamu visiting Mecca in 1441.

In 1506, the Portuguese fleet under Tristão da Cunha sent a ship to blockade Lamu, a few days later the rest of the fleet arrived forcing the king of the town to quickly concede to pay an annual tribute to them with 600 Meticals immediately.[5] The Portuguese action was prompted by the nation's successful mission to control trade along the coast of the Indian Ocean. For a considerable time, Portugal had a monopoly on shipping along the East African coast and imposed export taxes on pre-existing local channels of commerce. In the 1580s, prompted by Turkish raids, Lamu led a rebellion against the Portuguese. In 1652, Oman assisted Lamu to resist Portuguese control.[6]

"Golden Age"

Lamu's years as an Omani protectorate during the period from the late 17th century to the early 19th century mark the town's golden age. Lamu was governed as a republic under a council of elders known as the Yumbe who ruled from a palace in the town; little exists of the palace today other than a ruined plot of land.[7] During this period, Lamu became a center of poetry, politics, arts and crafts as well as trade. Many of the buildings of the town were constructed during this period in a distinct classical style.[7] Aside from its thriving arts and crafts trading, Lamu became a literary and scholastic centre. Woman writers such as the poet Mwana Kupona – famed for her Advice on the Wifely Duty – had a higher status in Lamu than was the convention in Kenya at the time.[7]

In 1812, a coalition Pate-Mazrui army invaded the archipelago during the Battle of Shela. They landed at Shela with the intention of capturing Lamu and completing the fort which had begun to be constructed, but were violently suppressed by the locals in their boats on the beach as they tried to flee.[7] In fear of future attacks, Lamu appealed to the Omanis for a Busaidi garrison to operate at the new fort and help protect the area from Mazrui rebels along the Kenyan coast.[7]

Colonial period

In the middle of the 19th century, Lamu came under the political influence of the sultan of Zanzibar. The Germans claimed Wituland in June 1885.[8] The Germans considered Lamu to be of strategical importance and an ideal place for a base.[9] From 22 November 1888 to 3 March 1891, there was a German post office in Lamu to facilitate communication within the German protectorate in the sultanate. It was the first post office to be established on the East African coast; today there is a museum in Lamu dedicated to it: the German Post Office Museum.[10] In 1890, Lamu and Kenya fell under British colonial rule by the terms of the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty. Kenya gained political independence in 1963, although the influence of the Kenyan central government has remained low, and Lamu continues to enjoy some degree of local autonomy.

Modern Lamu

In a 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund identified Lamu as one of 12 worldwide sites most "On the Verge" of irreparable loss and damage, citing insufficient management and development pressure as primary causes.[11]

While the terror group Al Shabaab kidnappings had placed Lamu off-limits in September 2011, by early 2012 the island was considered safe. On 4 April 2012, the US Department of State lifted its Lamu travel restriction.[12] However, two attacks in the vicinity of Lamu in July 2014, for which Al Shabaab claimed responsibility, led to the deaths of 29 people.[13]

Climate

Lamu has a tropical dry savanna climate (Köppen climate classification As).

| Climate data for Lamu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.9 (87.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.8 (85.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 6 (0.2) |

4 (0.2) |

25 (1.0) |

130 (5.1) |

329 (13.0) |

164 (6.5) |

75 (3.0) |

40 (1.6) |

39 (1.5) |

40 (1.6) |

39 (1.5) |

28 (1.1) |

919 (36.3) |

| Average rainy days | 1 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 85 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[14] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Lamu's economy was based on slave trade until abolition in the year 1907.[15] Other traditional exports included ivory, mangrove, turtle shells and rhinoceros horn, which were shipped via the Indian Ocean to the Middle East and India. In addition to the abolition of slavery, construction of the Uganda Railroad in 1901 (which started from the competing port of Mombasa) significantly hampered Lamu's economy.

Tourism has gradually refuelled the local economy in recent times, and it is a popular destination for backpackers. Many of the locals are involved in giving trips on dhows to tourists.[16] Harambee Avenue is noted for its cuisine, and has a range of stores including the halwa shop selling sweet treats and miniature mutton kebabs and cakes are sold at night.[17] Coconut, mango and grapefruit and seafood such as crab and lobster are common ingredients.[17] The town contains a central market, the Gallery Baraka and Shumi's Designs shop, and the Mwalimu Books store.[18]

.jpg)

The oldest hotel in the town, Petley's Inn, is situated on the waterfront.[3] Other hotels include the American-restored Amu House, the 20-room Bahari Hotel, Doda Villas, the Swedish-owned Jannat House, the 3-storey 23-room Lamu Palace Hotel, Petley's Inn, the 13-room Stone House Hotel, which was converted from an 18th-century house, and the 18-room Sunsail Hotel, a former trader's house on the waterfront with high ceilings.[19]

Mangroves are harvested for building poles, and Lamu has a sizeable artisan community, including carpenters who are involving in boat building and making ornate doors and furniture.[3]

The town is served by Lamu District Hospital to the south of the main centre, operated by the Ministry of Health. It was established in the 1980s,[20] and is one of the best-equipped hospitals on the Kenyan coast.[21]

China has begun feasibility studies to transform Lamu into the largest port in East Africa, as part of their String of Pearls strategy.[22]

Notable landmarks

The town was founded in the 14th century and it contains many fine examples of Swahili architecture. The old city is inscribed on the World Heritage List as "the oldest and best-preserved Swahili settlement in East Africa".

Once a center for the slave trade, the population of Lamu is ethnically diverse. Lamu was on the main Arabian trading routes, and as a result, the population is largely Muslim.[23] To respect the Muslim inhabitants, tourists in town are expected to wear more than shorts or bikinis.

There are several museums, including the Lamu Museum, home to the island's ceremonial horn (called siwa);[24] other museums are dedicated to Swahili culture and to the local postal service. Notable buildings in Lamu town include:

Lamu Fort

Lamu Fort is a fort in the town. Fumo Madi ibn Abi Bakr, the sultan of Pate, started to build the fort on the seafront, to protect members of his unpopular government. He died in 1809, before the first storey of the fort was completed. The fort was completed by the early 1820s.

Riyadha Mosque

Habib Salih, a Sharif with family connections to the Hadramaut, Yemen, settled on Lamu in the 1880s, and became a highly respected religious teacher. Habib Salih had great success gathering students around him, and in 1900 the Riyadha Mosque was built.[25] He introduced Habshi Maulidi, where his students sang verse passages accompanied by tambourines. After his death in 1935 his sons continued the madrassa, which became one of the most prestigious centres for Islamic studies in East Africa. The Mosque is the centre for the Maulidi Festival, which are held every year during the last week of the month of the Prophet's birth. During this festival, pilgrims from Sudan, Congo, Uganda, Zanzibar and Tanzania join the locals to sing the praise of Mohammad. Mnarani Mosque is also of note.

Donkey sanctuary

Since the island has no motorised vehicles, transportation and other heavy work is done with the help of donkeys. There are some 3000 donkeys on the island.[9] Dr. Elisabeth Svendsen of The Donkey Sanctuary in England first visited Lamu in 1985. Worried by the conditions for the donkeys, the Sanctuary was opened in 1987.[23] The Sanctuary provides treatment to all donkeys free of charge.

Culture

Lamu is home to the Maulidi Festival, held in January or February, which celebrates Mohammed's birth. It features a range of activities from "donkey races to dhow-sailing events and swimming competitions".[26] The Lamu Cultural Festival, a colourful carnival, [27] is usually held in the last week of August, which since 2000 has featured traditional dancing, crafts including kofia embroidery, and dhow races.[28] The Donkey Awards, with prizes given to the finest donkeys, are given in March/April.[28] Women's music in the town is also of note and they perform the chakacha, a wedding dance. Men perform the hanzua (a sword dance) and wear kanzus.[29]

Lamu Old Town was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2001, based on 3 criteria:

- The architecture and urban structure of Lamu graphically demonstrate the cultural influences that have come together there over several hundred years from Europe, Arabia, and India, utilising traditional Swahili techniques to produce a distinct culture.

- The growth and decline of the seaports on the East African coast and interaction between the Bantu, Arabs, Persians, Indians, and Europeans represents a significant cultural and economic phase in the history of the region which finds its most outstanding expression in Lamu Old Town.

- Its paramount trading role and its attraction for scholars and teachers gave Lamu an important religious function in the region, which it maintains to this day.[30]

Transport

In 2011, proposals were being advanced to build a deep-water port which would have much greater capacity in terms of depth of water, number of berths, and ability for vessels to arrive and depart at the same time than the country's main port at Mombasa.[31]

In popular culture

The song "Lamu"[32] by Christian singer Michael W. Smith is inspired by the island. In the song, Smith refers to Lamu as "an island hideaway...the place we soon will be a rebirth from life's demise...where the world is still". The song is about running away from life's problems.

Lamu is the setting of Anthony Doerr's short story "The Shell Collector" from his collection of stories by the same name.

Part of the events in the novel “Our Wild Sex in Malindi” (by Andrei Gusev) takes place in Lamu.[33][34][35]

See also

- Juma and the Magic Jinn, a United States children's picture book set on Lamu Island

- Lamu Port and Lamu-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor

References

- "2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume II: Distribution of Population by Administrative Units". Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Romero, Patricia (1997). Lamu. History, Society, and Family in an East African Port City. Marcus Wiener Publishers, p. 10

- This is Kenya. Struik. 2005. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84537-151-7.

- Oded, Arye (2000). Islam and Politics in Kenya. Lynne Rienner Publishers, p. 11

- Strandes, Justus (1971). "The Portuguese in East Africa". East African Literature Bureau. p.66.

- Jackson 2009, p. 89.

- Trillo 2002, p. 555.

- McIntyre & McIntyre 2013, p. 22.

- Fitzpatrick 2009, p. 330.

- "Lamu: German Post Office Historical – Background". National Museums of Kenya. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "GHF". Global Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "Security message and Travel Warning (April 4, 2012) | Embassy of the United States". Nairobi.usembassy.gov. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Akwiri, Joseph. "Gunmen kill at least 29 in latest raids on Kenyan coast". Reuters. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "World Weather Information Service – Lamu". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Transafrican Journal of History. East African Publishing House. 1980. p. 110.

- Trillo 2002, p. 565.

- Trillo 2002, p. 568.

- Trillo 2002, p. 558.

- Trillo 2002, p. 561.

- "THE SAD CASE OF MOKOWE LAMU DISTRICT HOSPITAL". Cmkn.org. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Fitzpatrick 2009, p. 328.

- "Future Kenya Port Could Mar Pristine Land". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Trillo 2002, p. 566.

- Fitzpatrick 2006, p. 343.

- Briggs 2010, p. 204.

- Bain, Bruyn & Williams 2010, p. 284.

- Ham, Butler & Starnes 2012, p. 215.

- Parkinson, Phillips & Gourlay 2006, p. 219.

- Senoga-Zake 1986, p. 68.

- Lamu Old Town, UNESCO

- African Business, May 2011

- "Artist, Christian, Worship Leader – Community, News, Tour Dates, Cruise and More". Michael W. Smith. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Review of "Our Wild Sex in Malindi" on the site of public fund "Union of writers of Moscow", 2020

- “Our Wild Sex in Malindi” by Andrei Gusev, 2020.

- «Наш жёсткий секс в Малинди» by Andrei Gusev in Lady’s Club (in Russian).

- Bibliography

- Allen, James de Vere: Lamu, with an appendix on Archaeological finds from the region of Lamu by H. Neville Chittick. Nairobi: Kenya National Museums.

- Bain, Keith; Bruyn, Pippa de; Williams, Lizzie (22 April 2010). Frommer's Kenya and Tanzania. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-64546-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckwith, Carol and Fisher, Angela, Text: Hancock, Graham: "African Ark, People and Ancient Cultures of Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa," New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc, 1990. ISBN 0-8109-1902-8

- Briggs, Philip (2010). Kenya Highlights. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-267-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Couffer, Jack: "The Cats of Lamu." New York: The Lyons Press, c1998. ISBN 1-85410-568-X

- Eliot, Charles (1966). The East African Protectorate. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-1661-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Engel, Ulf; Ramos, Manuel João (17 May 2013). African Dynamics in a Multipolar World. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25650-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzpatrick, Mary (2009). East Africa. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-769-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ghaidan, Usam: Lamu: A study of the Swahili town. Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau, 1975.

- Ham, Anthony; Butler, Stuart; Starnes, Dean (1 June 2012). Lonely Planet Kenya. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74321-306-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Guida M. (2009). Women Leaders of Africa, Asia, Middle East, and Pacific: A Biographical Reference. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4415-5843-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McIntyre, Chris; McIntyre, Susan (1 April 2013). Zanzibar. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-458-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Naipaul, Shiva: North of South, An African Journey, 1978. Page 177 ff, Penguin Travel, ISBN 978-0-14-018826-4

- Parkinson, Tom; Phillips, Matt; Gourlay, Will (2006). Kenya. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-743-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prins, A.H.J.: Sailing from Lamu: A Study of Maritime Culture in Islamic East Africa. Assen: van Gorcum & Comp., 1965.

- Romero, Patricia W.: Lamu: history, society, and family in an East African port city. Princeton, N.J.: Markus Wiener, c1997. ISBN 1-55876-106-3, ISBN 1-55876-107-1

- Senoga-Zake, George W. (1986). Folk Music of Kenya. Uzima Publishing House. ISBN 978-9966-855-02-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trillo, Richard (2002). Kenya. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-859-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)