Lahaul and Spiti district

The Lahaul and Spiti district in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh consists of the two formerly separate districts of Lahaul and Spiti. The present administrative centre is Keylong in Lahaul. Before the two districts were merged, Kardang was the capital of Lahaul, and Dhankar the capital of Spiti. The district was formed in 1960, and is the fourth least populous district in India (out of 640).[1]

Lahaul and Spiti district | |

|---|---|

District of Himachal Pradesh | |

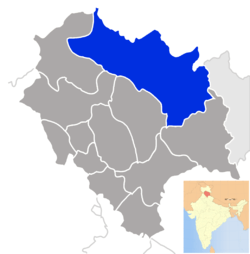

Location of Lahaul and Spiti district in Himachal Pradesh | |

| Country | India |

| State | Himachal Pradesh |

| Division | Two |

| Headquarters | Keylong |

| Government | |

| • Vidhan Sabha constituencies | 01 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13,833 km2 (5,341 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 31,564 |

| • Density | 2.3/km2 (5.9/sq mi) |

| • Urban | None |

| Demographics | |

| • Literacy | 86.97% (male), 66.5% (female) |

| • Sex ratio | 916 |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| Major highways | one (Manali-Leh National Highway) |

| Average annual precipitation | Scanty Rainfall mm |

| Website | https://hplahaulspiti.gov.in |

Kunzum la or the Kunzum Pass (altitude 4,551 m (14,931 ft)) is the entrance pass to the Spiti Valley from Lahaul. It is 21 km (13 mi) from Chandra Tal.[2] This district is connected to Manali through the Rohtang Pass. To the south, Spiti ends 24 km (15 mi) from Tabo, at the Sumdo where the road enters Kinnaur and joins with National Highway No. 5.[3]

The two valleys are quite different in character. Spiti is more barren and difficult to cross, with an average elevation of the valley floor of 4,270 m (14,010 ft). It is enclosed between lofty ranges, with the Spiti river rushing out of a gorge in the southeast to meet the Sutlej River. It is a typical mountain desert area with an average annual rainfall of only 170 mm (6.7 in).[4] The district has close cultural links with Ngari Prefecture of Tibet Autonomous Region.[5]

Flora and fauna

The harsh conditions of Lahaul permit only scattered tufts of hardy grasses and shrubs to grow, even below 4 km (13,000 ft). Glacier lines are usually found at 5 km (16,000 ft). Due to certain changes in climate, nowadays people are being able to grow some vegetables in the Lahaul valley e.g. cabbage, potato, green peas, radish, tomato, carrot and all types of leafy vegetables. The main cash crops are potatoes, cabbage, and green peas.

The valley has snow leopards,[6] foxes ibex, Himalayan brown bear, Musk Deer, and Himalayan blue sheep. There are two important protected areas in the region that are home to snow leopard and its prey including the Pin Valley National Park and Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. Animals such as yaks and dzos roam across the wild Lingti plains. However, over-hunting and a decrease in food supplies has led to a large decrease in the population of the Tibetan antelope, argali, kiangs, musk deer, and snow leopards in these regions, reducing them to the status of endangered species. Surprisingly, due to ardent religious beliefs, the locals of Spiti do not hunt these wild animals.

Apart from the exotic wildlife, the Valley of Spiti is also known for its wealth of flora and the profusion of wild flowers. Some of the most common species found here include Causinia thomsonii, Seseli trilobum, Crepis flexuosa, Caragana brevifolia and Krascheninikovia ceratoides. Then there are more than 62 species of medicinal plants found here.

People

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 12,392 | — |

| 1911 | 12,981 | +0.47% |

| 1921 | 12,836 | −0.11% |

| 1931 | 13,733 | +0.68% |

| 1941 | 14,594 | +0.61% |

| 1951 | 15,338 | +0.50% |

| 1961 | 23,682 | +4.44% |

| 1971 | 27,568 | +1.53% |

| 1981 | 32,100 | +1.53% |

| 1991 | 31,294 | −0.25% |

| 2001 | 33,224 | +0.60% |

| 2011 | 31,564 | −0.51% |

| source:[7] | ||

According to the 2011 census Lahaul and Spiti district has a population of 31,564. This gives it a ranking of 638th in India (out of a total of 640).[1] The district has a population density of 2 inhabitants per square kilometre (5.2/sq mi).[1] Its population growth rate over the decade 2001-2011 was -5%.[1] Lahul and Spiti has a sex ratio of 903 females for every 1000 males, and a literacy rate of 76.81%.[1]

At the 2011 census, 41% of the population in the district had Kinnauri as their first language, 27% – Pattani, 3.0% – Bhotia, 2.9% – Hindi, 2.8% – Nepali, and 2.6% – Tibetan.[8]

The language, culture, and populations of Lahaul and Spiti are closely related. Generally, the Lahaulis are of Tibetan and Indo-Aryan, while the Spiti Bhot are more similar to the Tibetans, owing to their proximity to Tibet. The district has a Himachal Pradesh state legislative law in place to curb antique loot, by suspecting travellers given past incidences. In pre-independence era, the ethnic tribal belt was into the British lahaul and the chamba lahaul, which was merged with Punjab post 1947. This is the second largest district in the Indian union.

The language spoken by both the Lahauli and Spiti is Spiti Bhoti, a Tibetic language of the Western Innovative subgroup. They are very similar to the Ladakhi and Tibetans culturally, as they had been placed under the rule of the Guge and Ladakh kingdoms at occasional intervals.

Among the Lahaulis, the family acts as the basic unit of kinship. The extended family system is common, evolved from the polyandric system of the past. The family is headed by a senior male member, known as the Yunda, while his wife, known as the Yundamo, attains authority by being the oldest member in the generation. The clan system, also known as Rhus, plays another major role in the Lahauli society.

The Spiti Bhot community has an inheritance system that is otherwise unique to the Tibetans. Upon the death of both parents, only the eldest son will inherit the family property, while the eldest daughter inherits the mother's jewellery, and the younger siblings inherit nothing. Men usually fall back on the social security system of the Trans-Himalayan Gompas.

Lifestyle

The lifestyles of the Lahauli and Spiti Bhot are similar, owing to their proximity. Polyandry was widely practiced by the Lahaulis in the past, although this practice has been dying out. The Spiti Bhot do not generally practice polyandry any more, although it is accepted in a few isolated regions.

Divorces are accomplished by a simple ceremony performed in the presence of village elders. Divorce can be sought by either partner. The husband has to pay compensation to his ex-wife if she does not remarry. However, this is uncommon among the Lahaulis.

Agriculture is the main source of livelihood. Potato farming is common. Occupations include animal husbandry, working in government programs, government services, and other businesses and crafts that include weaving. Houses are constructed in the Tibetan architectural style, as the land in Lahul and Spiti is mountainous and quite prone to earthquakes.[9]

Religion

Most of the Lahaulis follow a combination of Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism of the Drukpa Kagyu order, while the Spiti Bhotia follow Tibetan Buddhism of the Gelugpa order. Within Lahoul, the Todh-Gahr (upper region of Lahaul towards Ladhakh) region had the strongest Buddhist influence, owing to its close proximity to Spiti. This bas-relief, of marble, depicts the Buddhist deity Avalokiteshvara (the embodiment of the Buddha's compassion) in a stylized seated position; Hindu devotees take it to be Shiva Nataraj, Shiva dancing. This image appears to be of sixteenth-century Chamba craftsmanship. It was created to replace the original black stone image of the deity, which became damaged by art looters. This original image is kept beneath the plinth of the shrine. It appears to be of 12th century Kashmiri provenance. Much of the art thieves are active in this remote belt because of neglected gompas and temples. Raja Ghepan, one of the major deities is greatly worshipped by almost all Lahauli.

Before the spread of Tibetan Buddhism and Hinduism, the people were adherents of the religion 'Lung Pe Chhoi', an animistic religion that had some affinities with the Bön religion of Tibet. While the religion flourished, animal and human sacrifices were regularly offered up to the 'Iha', a term that refers to evil spirits residing in the natural world, notably in the old pencil-cedar trees, rocks, and caves. Vestiges of the Lung Pe Chhoi religion can be seen in the behaviour of the Lamas, who are believed to possess certain supernatural powers.

The Losar festival (also known as Halda in Lahauli) is celebrated between the months of January and February. The date of celebration is decided by the Lamas. It has the same significance as the Diwali festival of Hinduism, but is celebrated in a Tibetan fashion.

At the start of the festival, two or three persons from every household will come holding burning incense. The burning sticks are then piled into a bonfire. The people will then pray to Shiskar Apa, the goddess of wealth (other name Vasudhara) in the Buddhist religion.

Tourism

The natural scenery and Buddhist monasteries, such as Kye, Dhankar, Shashur, Guru Ghantal, Khungri Monastery in Pin Valley, Tnagyud Gompa of the Sakya Sect in Komic, Sherkhang Gompa in Lahlung (believed to be older than Tabo Monastery), the only Buddhist Mummy of a Monk in Gue around 550 years old and Chandra Taal Lake are the main tourist attractions of the region.

One of the most interesting places is the Tabo Monastery, located 45 km from Kaza, Himachal Pradesh, the capital of the Spiti region. This monastery rose to prominence when it celebrated its thousandth year of existence in 1996. It houses a collection of Buddhist scriptures, Buddhist statues and Thangkas. The ancient gompa is finished with mud plaster, and contains several scriptures and documents. Lama Dzangpo heads the gompa here. There is a modern guest house with a dining hall and all facilities are available.

Another gompa, Kardang Monastery, is located at an elevation of 3,500 metres across the river, about 8 km from Keylong. Kardang is well connected by the road via the Tandi bridge which is about 14 km from Keylong. Built in the 12th century, this monastery houses a large library of Buddhist literature including the main Kangyur and Tangyur scriptures.

The treacherous weather in Lahaul and Spiti permits visitors to tour only between the months of June to October, when the roads and villages are free of snow and the high passes (Rothang La and Kunzum La) are open. It is possible to access Spiti from Kinnaur (along the Sutlej) all through the year, although the road is sometimes temporarily closed by landslides or avalanches.

Buddhist monasteries

Spiti is one of the important centers of Buddhism in Himachal Pradesh. It is popularly known as the 'land of lamas'. The valley is dotted by numerous Buddhist Monasteries or Gompas.

Kye Monastery: Kye Monastery is one of the main learning centres of Buddhist studies in Spiti. The monastery is house to some 100 odd monks who receive education here. It is the oldest and biggest monastery in Spiti. It houses rare paintings and scriptures of Buddha and other gods and goddess. There are also rare 'Thangka' paintings and ancient musical instruments 'trumpets, cymbals, and drums in the monastery.

Tabo Monastery: Perched at an altitude of 3050 meters, Tabo Monastery is often referred to as the 'Ajanta of the Himalayas'. The 10th century Tabo Monastery was founded by the great scholar, Richen Zangpo. The monastery houses more than 60 lamas and contains the rare collection of scriptures, pieces of art, wall paintings -Thankas and Stucco.

Adventure activities

To-do-Trails: For trekkers, the Spiti Valley is a paradise, offering challenging treks to explore the new heights of the Himalayas. The treks take people to the most remote areas including the rugged villages and old Gompas followed by the exotic wildlife trails. Some of the trekking routes in the area include Kaza-Langza-Hikim-Komic-Kaza, Kaza-Ki-Kibber-Gete-Kaza, Kaza-Losar-Kunzum La and Kaza-Tabo-Sumdo-Nako. There are some very high altitude treks also where you have to cross passes- like Parangla Pass (connecting Ladakh with Spiti Valley), Pin Parvati Pass, Baba Pass, Hamta Pass trek, Spiti Left Bank Trek are few to name.

Skiing: Skiing is the popular adventure sports in Spiti.

Yak Safari: Yak can be used to see the flora and fauna of trans-Himalayan desert.

Gallery

- Lahaul Valley in winter

Waterfall near Udaipur town in Lahaul Valley

Waterfall near Udaipur town in Lahaul Valley Mountain peak

Mountain peak Kunzum Pass between Lahul and Spiti

Kunzum Pass between Lahul and Spiti

See also

References

- "District Census 2011". Census2011.co.in. 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Kunzum Pass". india9.com.

- Kapadia (1999). pp. 215-216.

- Kapadia (1999). pp. 26-27.

- "Kinnaur-Ngari Corridor: An Argument for The Revival of The Western Himalayan Silk Route - Himachal Watcher". Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Snow Leopard Sightings Rising in Spiti valley". Raacho Trekkers.

- Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901

- "C-16 Population By Mother Tongue - Himachal Pradesh". censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "References - Lahaul Spiti Travel - Lahaul Spiti Tourist Guide". Lahaul Spiti Travel - Lahaul Spiti Tourist Guide. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Census of India: District Profile". Censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Bindloss, Joe; Singh, Sarina (2007). India. Lonely Planet. pp. 343. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2.

Bibliography

- Ciliberto, Jonathan. (2013). "Six Weeks in the Spiti Valley". Circle B Press. 2013. Atlanta. ISBN 978-0-9659336-6-7

- Handa, O. C. (1987). Buddhist Monasteries in Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85182-03-5.

- Hutchinson, J. & J. PH Vogel (1933). History of the Panjab Hill States, Vol. II. (1st ed) Lahore: Govt. Printing, Punjab, 1933. Reprint 2000. Department of Language and Culture, Himachal Pradesh. Chapter X Lahaul, pp. 474–483; Spiti, pp. 484–488.

- Kapadia, Harish. (1999). Spiti: Adventures in the Trans-Himalaya. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7387-093-4.

- Janet Rizvi. (1996). Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Delhi. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Cunningham, Alexander. (1854). LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries. London. Reprint: Sagar Publications (1977).

- Francke, A. H. (1977). A History of Ladakh. (Originally published as, A History of Western Tibet, (1907). 1977 Edition with critical introduction and annotations by S. S. Gergan & F. M. Hassnain. Sterling Publishers, New Delhi.

- Francke, A. H. (1914). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- Banach, Benti (2010). 'A Village Called Self-Awareness, life and times in Spiti Valley'. Vajra Publications, Kathmandu ISBN 9937506441.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lahul and Spiti district. |

- Official Website of the district