Himalayan brown bear

The Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), also known as the Himalayan red bear, isabelline bear or Dzu-Teh, is a subspecies of the brown bear and is known from northern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, northern India, west China and Nepal. It is the largest mammal in the region, males reaching up to 2.2 m (7 ft) long while females are a little smaller. These bears are omnivorous and hibernate in a den during the winter. While the brown bear as a species is classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, this subspecies is highly endangered and populations are dwindling. It is Endangered in the Himalayas and Critically Endangered in Hindu Kush.

| Himalayan brown bear | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ursidae |

| Genus: | Ursus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | U. a. isabellinus |

| Trinomial name | |

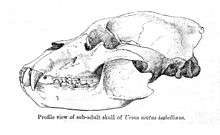

| Ursus arctos isabellinus Horsfield, 1826 | |

| |

| Himalayan brown bear range | |

Description

Himalayan brown bears exhibit sexual dimorphism. Males range from 1.5m up to 2.2m (5 ft - 7 ft 3in) long, while females are 1.37m to 1.83m (4 ft 6 in - 6 ft) long. They are the largest animals in the Himalayas and are usually sandy or reddish-brown in colour.

Distribution

The bears are found in Nepal, Tibet, west China, north India, north Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, entire Kyrgyzstan and south-east Kazakhstan.[2] They are already speculated to have become extinct in Bhutan. Phylogenetic analysis has shown that the Gobi bear clusters with the Himalayan brown bear and may represent a relict population of this subspecies.[3]

Phylogenetics and evolution

The Himalayan brown bear consists of a single clade that is the sister group to all other brown bears (and polar bears). The dating of the branching event, estimated at 658,000 years ago, corresponds to the period of a Middle Pleistocene episode of glaciation on the Tibetan plateau, suggesting that during this Nyanyaxungla glaciation the lineage that would give rise to the Himalayan brown bear became isolated in a distinct refuge, leading to its divergence.[3]

Behaviour and ecology

The bears go into hibernation around October and emerge during April and May. Hibernation usually occurs in a den or cave made by the bear.

Status and conservation

International trade is prohibited by the Wildlife Protection Act in India. Snow Leopard Foundation (SLF) in Pakistan conducts research on the current status of Himalayan brown bears in the Pamir Range in Gilgit-Baltistan, a promising habitat for the bears and a wildlife corridor connecting bear populations in Pakistan to central Asia. The project also intends to investigate the conflicts humans have with the bears, while promoting tolerance for bears in the region through environmental education. SLF received funding from the Prince Bernhard Nature Fund and Alertis.[4] Unlike other brown bear subspecies, which are found in good numbers,[1] the Himalayan brown bear is critically endangered. They are poached for their fur and claws for ornamental purposes and internal organs for use in medicines. They are killed by shepherds to protect their livestock and their home is destroyed by human encroachment. In Himachal, their home is the Kugti and Tundah wildlife sanctuaries and the tribal Chamba region. Their estimated population is just 20 in Kugti and 15 in Tundah. The tree bearing the state flower of Himachal, buransh, is the favourite hangout of the bear. Due to the high value of the buransh tree, it is being commercially cut causing further destruction to the brown bear’s home.[5] The Himalayan brown bear is a critically endangered species in some of its range with a population of only 150-200 in Pakistan. The populations in Pakistan are slow reproducing, small, and declining because of habitat loss, fragmentation, poaching, and bear-baiting.[4] In India, brown bears are present in 23 protected areas in the northern states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttaranchal, but only in two of these the bears are regarded as fairly common.There are likely less than 1,000 bears, and possibly half that in India.[6]

Association with the Yeti

"Dzu-Teh," a Nepalese term, has also been associated with the legend of the Yeti, or Abominable Snowman, with which it has been sometimes confused or mistaken. During the Daily Mail Abominable Snowman Expedition of 1954, Tom Stobart encountered a "Dzu-Teh". This is recounted by Ralph Izzard, the Daily Mail correspondent on the expedition, in his book The Abominable Snowman Adventure.[7] A 2017 analysis of DNA extracted from a mummified animal purporting to represent a Yeti was shown to have been a Himalayan brown bear.[3]

References

- McLellan, B.N.; Proctor, M.F.; Huber, D. & Michel, S. (2017). "Ursus arctos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T41688A121229971. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T41688A121229971.en.

- Anarbaev; et al. (2019). "Conservation Distribution and Conservation Status of Tien-Shan Brown Bear in the Kyrgyz Republic". www.researchgate.net.

- Lan T.; Gill S.; Bellemain E.; Bischof R.; Zawaz M.A.; Lindqvist C. (2017). "Evolutionary history of enigmatic bears in the Tibetan Plateau–Himalaya region and the identity of the yeti". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1868): 20171804. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1804. PMC 5740279. PMID 29187630.

- "Alertis Secures Grant". Bears In Mind. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Tehsin, Arefa (2014-11-20). "Missing snowman". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- Ralph Izzard. (1955). "The Abominable Snowman Adventure". Hodder and Staoughton.

Further reading

- "Status and Affinities of the Bears of Northeastern Asia", by Ernst Schwarz Journal of Mammalogy 1940 American Society of Mammalogists.

- Ogonev, S.I. 1932, "The mammals of eastern Europe and northern Asia", vol. 2, pp. 11–118. Moscow.

- Pocock R.I, "The Black and Brown Bears of Europe and Asia" Part 1. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 772–823, figs 1-11. July 15, 1932.

- Ursus arctos, by Maria Pasitschniak, Published 23 April 1993 by "The American Society of Mammalogists"

- John A. Jackson, "More than Mountains", Chapter 10 (pp 92) & 11, "Prelude to the Snowman Expedition & The Snowman Expedition", George Harrap & Co, 1954

- Charles Stonor, "The Sherpa and the Snowman", recounts the 1955 Daily Mail "Abominable Snowman Expedition" by the scientific officer of the expedition, this is a very detailed analysis of not just the "Snowman" but the flora and fauna of the Himalaya and its people. Hollis and Carter, 1955.

- John A. Jackson, "Adventure Travels in the Himalaya" Chapter 17, "Everest and the Elusive Snowman", 1954 updated material, Indus Publishing Company, 2005.

| Wikispecies has information related to Ursus arctos |