Lagash

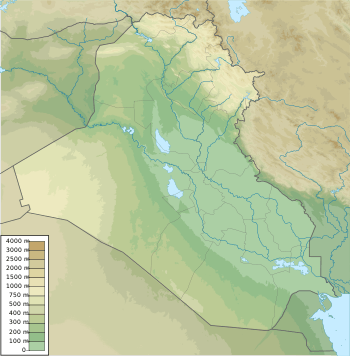

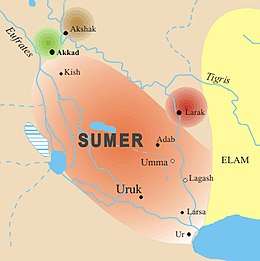

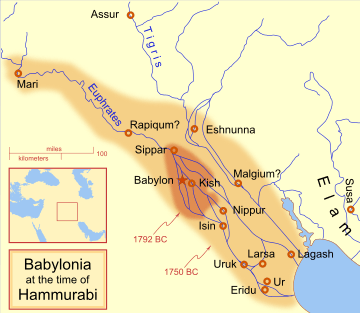

Lagash,[4]/ˈleɪɡæʃ/ (cuneiform: 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠 LAGAŠKI; Sumerian: Lagaš), or Shirpurla, was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Ash Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash (modern Al-Hiba) was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina (modern Surghul) is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu (modern Telloh), about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. Lagash's main temple was the E-Ninnu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. Lagash seems to have incorporated the ancient cities of Girsu, Nina, Uruazagga and Erim.[5]

.jpg) | |

Lagash Shown within Near East  Lagash Lagash (Iraq) | |

| Location | Ash Shatrah, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°24′41″N 46°24′26″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 400 to 600 ha |

| History | |

| Founded | 3rd millennium BCE |

History

From inscriptions found at Girsu such as the Gudea cylinders, it appears that Lagash was an important Sumerian city in the late 3rd millennium BCE. It was at that time ruled by independent kings, Ur-Nanshe (24th century BCE) and his successors, who were engaged in contests with the Elamites on the east and the kings of Kienĝir and Kish on the north. Some of the earlier works from before the Akkadian conquest are also extremely interesting, in particular Eanatum's Stele of the Vultures and Entemena's great silver vase ornamented with Ningirsu's sacred animal Anzû: a lion-headed eagle with wings outspread, grasping a lion in each talon. With the Akkadian conquest Lagash lost its independence, its ruler or ensi becoming a vassal of Sargon of Akkad and his successors; but Lagash continued to be a city of much importance and above all, a centre of artistic development.

After the collapse of Sargon's state, Lagash again thrived under its independent kings (ensis), Ur-Baba and Gudea, and had extensive commercial communications with distant realms. According to his own records, Gudea brought cedars from the Amanus and Lebanon mountains in Syria, diorite from eastern Arabia, copper and gold from central and southern Arabia, while his armies were engaged in battles with Elam on the east. His was especially the era of artistic development. We even have a fairly good idea of what Gudea looked like, since he placed in temples throughout his city numerous statues or idols depicting himself with lifelike realism, (Statues of Gudea). At the time of Gudea, the capital of Lagash was actually in Girsu. The kingdom covered an area of approximately 1,600 square kilometres (620 sq mi). It contained 17 larger cities, eight district capitals, and numerous villages (about 40 known by name). According to one estimate, Lagash was the largest city in the world from c. 2075 to 2030 BC.[6]

Soon after the time of Gudea, Lagash was absorbed into the Ur III state as one of its prime provinces.[7] There is some information about the area during the Old Babylonian period. After that it seems to have lost its importance; at least we know nothing more about it until the construction of the Seleucid fortress mentioned, when it seems to have become part of the Greek kingdom of Characene.

First dynasty of Lagash (c.2500-2300 BCE)

The dynasties of Lagash are not found on the Sumerian King List, although one extremely fragmentary supplement has been found in Sumerian, known as The Rulers of Lagash.[8] It recounts how after the flood mankind was having difficulty growing food for itself, being dependent solely on rainwater; it further relates that techniques of irrigation and cultivation of barley were then imparted by the gods. At the end of the text is the statement "Written in the school", suggesting this was a scribal school production. A few of the names from the Lagash rulers listed below may be made out, including Ur-Nanshe, "Ane-tum", En-entar-zid, Ur-Ningirsu, Ur-Bau, and Gudea.

The First dynasty of Lagash is dated to the 25th century BCE. En-hegal is recorded as the first known ruler of Lagash, being tributary to Uruk. His successor Lugal-sha-engur was similarly tributary to Mesilim. Following the hegemony of Mesannepada of Ur, Ur-Nanshe succeeded Lugal-sha-engur as the new high priest of Lagash and achieved independence, making himself king. He defeated Ur and captured the king of Umma, Pabilgaltuk. In the ruins of a building attached by him to the temple of Ningirsu, terracotta bas reliefs of the king and his sons have been found, as well as onyx plates and lions' heads in onyx reminiscent of Egyptian work.[9] One inscription states that ships of Dilmun (Bahrain) brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands. He was succeeded by his son Akurgal.

Eannatum, grandson of Ur-Nanshe, made himself master of the whole of the district of Sumer, together with the cities of Uruk (ruled by Enshakushana), Ur, Nippur, Akshak, and Larsa.[9] He also annexed the kingdom of Kish; however, it recovered its independence after his death.[9] Umma was made tributary—a certain amount of grain being levied upon each person in it, that had to be paid into the treasury of the goddess Nina and the god Ningirsu.[9] Eannatum's campaigns extended beyond the confines of Sumer, and he overran a part of Elam, took the city of Az on the Persian Gulf, and exacted tribute as far as Mari; however many of the realms he conquered were often in revolt. During his reign, temples and palaces were repaired or erected at Lagash and elsewhere; the town of Nina—that probably gave its name to the later Niniveh—was rebuilt, and canals and reservoirs were excavated. Eannatum was succeeded by his brother, En-anna-tum I. During his rule, Umma once more asserted independence under Ur-Lumma, who attacked Lagash unsuccessfully. Ur-Lumma was replaced by a priest-king, Illi, who also attacked Lagash.

His son and successor Entemena restored the prestige of Lagash.[9] Illi of Umma was subdued, with the help of his ally Lugal-kinishe-dudu or Lugal-ure of Uruk, successor to Enshakushana and also on the king-list. Lugal-kinishe-dudu seems to have been the prominent figure at the time, since he also claimed to rule Kish and Ur. A silver vase dedicated by Entemena to his god is now in the Louvre.[9] A frieze of lions devouring ibexes and deer, incised with great artistic skill, runs round the neck, while the Anzû crest of Lagash adorns the globular part. The vase is a proof of the high degree of excellence to which the goldsmith's art had already attained.[9] A vase of calcite, also dedicated by Entemena, has been found at Nippur.[9] After Entemena, a series of weak, corrupt priest-kings is attested for Lagash. The last of these, Urukagina, was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms, and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (En-hegal) |  | c. 2570 BCE | One inscription known, recording a purchase of land.[10] |

| (Lugal-sha-engur) | c. 2550 BCE | High priest or ensi. Mentioned as Ensi of Lagash in a unique inscription on the macehead of Mesilim: “Mesilim, king of Kish, builder of the temple of Ningirsu, brought [this mace head] for Ningirsu, Lugalshaengur [being] prince of Lagash”.[11] | |

| Ur-Nanshe (Ur-nina) |  | c. 2500 BCE | King ("Lugal") |

| Akurgal |  | c. 2500 BCE | King, son of Ur-Nanshe |

| Eannatum | c. 25th century BCE | Grandson of Ur-Nanshe, king, took Sumer away from Enshagkushana of Uruk and repulsed the armies of Kish, Elam and Mari | |

| Enannatum I | c. 25th century BCE | brother to Eanatum, high priest, Ur-Luma and Illi of Umma, as well as Kug-Bau of Kish gained independence from him. | |

| Entemena |  | c. 25th century BCE | Son of Enanatum I, king, contemporary with Lugal-ure (or Lugalkinishedudu) of Uruk and defeated Illi of Umma |

| Enannatum II | Son of Entemena, last member of the dynasty of Ur-Nanshe. | ||

| Enentarzi | A priest of Lagash. | ||

| Lugalanda | |||

| Urukagina | c. 2300 BCE | king, defeated by Lugalzagesi of Uruk, issued a proclamation of social reforms. |

The cuneiform text states that Enannatum I reminds the gods of his prolific temple achievements in Lagash. Circa 2400 BCE. From Girsu, Iraq. The British Museum, London

The cuneiform text states that Enannatum I reminds the gods of his prolific temple achievements in Lagash. Circa 2400 BCE. From Girsu, Iraq. The British Museum, London The name "Lagash" (𒉢𒁓𒆷) in vertical cuneiform of the time of Ur-Nanshe.

The name "Lagash" (𒉢𒁓𒆷) in vertical cuneiform of the time of Ur-Nanshe.

Border conflict with Umma (c.2500-2300 BCE)

In c. 2450 BCE, Lagash and the neighbouring city of Umma fell out with each other after a border dispute. As described in Stele of the Vultures the current king of Lagash, Eannatum, inspired by the patron god of his city, Ningirsu, set out with his army to defeat the nearby city. Initial details of the battle are unclear, but the Stele is able to portray a few vague details about the event. According to the Stele's engravings, when the two sides met each other in the field, Eannatum dismounted from his chariot and proceeded to lead his men on foot. After lowering their spears, the Lagash army advanced upon the army from Umma in a dense Phalanx. After a brief clash, Eannatum and his army had gained victory over the army of Umma. Despite having been struck in the eye by an arrow, the king of Lagash lived on to enjoy his army's victory. This battle is one of the earliest organised battles known to scholars and historians.[13]

.jpg) The armies of Lagash led by Eannatum in their conflict against Umma.

The armies of Lagash led by Eannatum in their conflict against Umma..jpg) Lancers of the army of Lagash against Umma

Lancers of the army of Lagash against Umma

Destruction of Lagash by the Akkadian Empire (circa 2300 BCE)

In his conquest of Sumer circa 2300 BCE, Sargon of Akkad, after conquering and destroying Uruk, then conquered Ur and E-Ninmar and "laid waste" the territory from Lagash to the sea, and from there went on to conquer and destroy Umma, and he collected tribute from Mari and Elam. He triumphed over 34 cities in total.[16]

Sargon's son and successor Rimush faced widespread revolts, and had to reconquer the cities of Ur, Umma, Adab, Lagash, Der, and Kazallu from rebellious ensis.[17]

Rimush introduced mass slaughter and large scale destruction of the Sumerian city-states, and maintained meticulous records of his destructions.[18] Most of the major Sumerian cities were destroyed, and Sumerian human losses were enormous: for the cities of Ur and Lagash, he records 8,049 killed, 5,460 "captured and enslaved" and 5,985 "expelled and annihilated".[18][19]

Stele of the victory of Rimush over Lagash

A Victory Stele in several fragments (three in total, Louvre Museum AO 2678)[20] has been attributed to Rimush on stylistic and epigraphical grounds. One of the fragments mentions Akkad and Lagash.[21] It is thought that the stele represents the defeat of Lagash by the troops of Akkad.[22] The stele was excavated in ancient Girsu, one of the main cities of the territory of Lagash.[23]

Detail

Detail.jpg)

Second dynasty of Lagash (c. 2260–2110 BCE)

This period lasted c. 2260–2110 BCE (Middle chronology). These rulers achieved a Sumerian revival, following the rise and fall of the Semitic Akkadian Empire, and the conquests of the Gutian dynasty.[28] The Second dynasty of Lagash rose at the time the Gutians were ruling in central Mesopotamia.[28] The rulers of Lagash, only taking the title of Ensi, or Governors, achieved to maintain a high level of independence from the Gutians in the southernmost areas of Mesoptamia.[28] Under Gudea, Lagash had a golden age, and seemed to enjoy a high level of independence from the Gutians.[28]

| Ruler | Proposed reign (short chronology) | Proposed reign (middle chronology) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lugal-ushumgal) | 2164 – 2146 BCE | 2230 – 2210 BCE | Vassal of Akkadian Empire rulers Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri | |

| (Puzer-Mama) | Wrested independence from the Akkadian Empire | |||

| Ur-Ningirsu I[29][30] | ||||

| Pirig-me or Ugme | Son of Ur-Ningirsu I.[29][31] | |||

| Lu-Baba[32] | ||||

| Lugula[33] | ||||

| Kaku or Kakug[34] | ||||

| Ur-Baba |  | 2093–2080 BCE | 2157 – 2144 BCE | |

| Gudea |  | 2080–2060 BCE | 2144––2124 BCE | Son-in-law of Ur-baba |

| Ur-Ningirsu |  | 2060–2055 BCE | 2124–2119 BCE | Son of Gudea |

| Ur-gar | 2053–2049 BCE | 2117–2113 BCE | ||

| Nam-mahani | 2049–2046 BCE | 2113–2110 BCE | Grandson of Kaku, defeated by Ur-Namma | |

Archaeology

Lagash is one of the largest archaeological mounds in the region, measuring roughly 3 by 1.5 km (2 by 1 mi). Estimates of its area range from 400 to 600 hectares (990 to 1,480 acres). The site is divided by the bed of a canal/river, which runs diagonally through the mound. The site was first excavated, for six weeks, by Robert Koldewey in 1887.[35] It was inspected during a survey of the area by Thorkild Jacobsen and Fuad Safar in 1953, finding the first evidence of its identification as Lagash. The major polity in the region of al-Hiba and Tello had formerly been identified as ŠIR.BUR.LA (Shirpurla).[36] Tell Al-Hiba was again explored in five seasons of excavation between 1968 and 1976 by a team from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University. The team was led by Vaughn E. Crawford, and included Donald P. Hansen and Robert D. Biggs. The primary focus was the excavation of the temple Ibgal of Inanna and the temple Bagara of Ningirsu, as well as an associated administrative area.[37][38][39][40]

The team returned 12 years later, in 1990, for a final season of excavation led by D. P. Hansen. The work primarily involved areas adjacent to an, as yet, unexcavated temple. The results of this season have apparently not yet been published.[41]

In March-April 2019, field work resumed under the University of Cambridge Lagash Archaeological Project.

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Short chronology timeline

References

- "ETCSLsearch". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary. "Lagash." Accessed 19 Dec 2010.

- "ePSD: lagaš[storehouse]". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Sumerian: Lagaški; cuneiform logogram: 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠, [NU11.BUR].LAKI[1] or [ŠIR.BUR].LAKI, "storehouse;"[2] Akkadian: Nakamtu;[3] modern Tell al-Hiba, Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq

- Williams, Henry (2018). Ancient Mesopotamia. Ozymandias Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-5312-6292-1.

- Tertius Chandler, Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census (Edwin Mellen Press, 1987) ISBN 0-88946-207-0

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz, "Kaku of Ur and Kaku of Lagash", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 43 (1984), pp. 339–42

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry; King, Leonard William; Jastrow, Morris (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–112.

- "Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative".

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "Vase of Lugalzagezi". British Museum. British Museum.

- Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 978-1-74033-593-5.

- Heuzey, Léon (1895). "Le Nom d'Agadé Sur Un Monument de Sirpourla". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 3 (4): 113–117. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284246.

- Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- "MS 2814 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- Crowe, D. (2014). War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-137-03701-5.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Heuzey, Léon (1895). "Le Nom d'Agadé Sur Un Monument de Sirpourla". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 3 (4): 113–117. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284246.

- Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- Heuzey, Léon (1895). "Le Nom d'Agadé Sur Un Monument de Sirpourla". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 3 (4): 113–117. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284246.

- "Musée du Louvre-Lens - Portail documentaire - Stèle de victoire du roi Rimush (?)". ressources.louvrelens.fr (in French).

- McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 235. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

- Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- Foster, Benjamin R. (1985). "The Sargonic Victory Stele from Telloh". Iraq. 47: 15–30. doi:10.2307/4200229. JSTOR 4200229.

- Corporation, Marshall Cavendish (2010). Ancient Egypt and the Near East: An Illustrated History. Marshall Cavendish. p. 54–56. ISBN 978-0-7614-7934-5.

- Edzard, Sibylle; Edzard, Dietz Otto (1997). Gudea and His Dynasty. University of Toronto Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8020-4187-6.

- "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- Robert Koldewey, "Die altbabylonischen Graber in Surghul und El-Hibba", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 2 (1887), pp. 403–30

- Amiaud, Arthur. "The Inscriptions of Telloh." Records of the Past, 2nd Ed. Vol. I. Ed. by A. H. Sayce, 1888. Accessed 19 Dec 2010. M. Amiaud notes that a Mr. Pinches (in his Guide to the Kouyunjik Gallery) contended ŠIR.BUR.LAki could be a logographic representation of "Lagash," but inconclusively.

- Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba, 1968–1969: A Preliminary Report", Artibus Asiae, 32 (1970), pp. 243–58

- Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba, 1970–1971: A Preliminary Report", Artibus Asiae, 35 (1973), pp. 62–70

- Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba: A summary of four seasons of excavation: 1968–1976", Sumer, 34 (1978), pp. 72–85

- Vaughn E. Crawford, "Inscriptions from Lagash, Season Four, 1975–76", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 29 (1977), pp. 189–222

- "Excavations in Iraq 1989–1990", Iraq, 53 (1991), pp. 169–82

Sources

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lagash |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lagash. |

- Robert D. Biggs, "Inscriptions from al-Hiba-Lagash : the first and second seasons", Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. 3, Undena Publications, 1976, ISBN 0-89003-018-9

- E. Carter, "A surface survey of Lagash, al-Hiba", 1984, Sumer, vol. 46/1-2, pp. 60–63, 1990

- Donald P. Hansen, "Royal building activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period", Biblical Archaeologist, vol. 55, pp. 206–11, 1992

- Vaughn E. Crawford, "Lagash", Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 29–35, 1974

- R. D. Biggs, "Pre-Sargonic Riddles from Lagash", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 32, no. 1/2, pp. 26–33, 1973

External links

- University of Cambridge Lagash project

- Lagash excavation site photographs at the Oriental Institute

- Lagash Digital Tablets at CDLI

- The Al-Hiba Publication Project

- The Al-Hiba Publication Project - digitization

.jpg)