Mesannepada

Mesannepada (Sumerian: 𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕, mes-an-ne2-pad3-da), Mesh-Ane-pada or Mes-Anne-pada ("Youngling chosen by An") was the first king listed for the First Dynasty of Ur (ca. the 25th century BC) on the Sumerian king list.[5] He is listed to have ruled for 80 years, having overthrown Lugal-kitun of Uruk: "Then Unug (Uruk) was defeated and the kingship was taken to Urim (Ur)".[6] In one of his seals, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, he is also described as king of Kish.[7][8]

| Mesannepada 𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kish, King of Ur | |

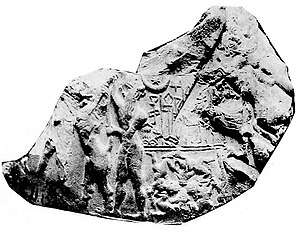

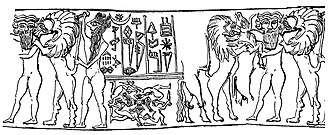

Cylinder seal impression of "Mesanepada, king of Kish", excavated in the Royal Cemetery at Ur (U. 13607).[1][2][3] The seal shows Gilgamish and the mythical bull between two lions, one of the lions biting him in the shoulder. On each side of this group appears Enkidu and a hunter-hero, with a long beard and a Kish-style headdress, armed with a dagger. Under the text, four runners with beard and long hair form a human Swastika. They are armed with daggers and catch each other's foot.[3] University of Pennsylvania. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, UPM 31.16.677.[4] | |

| Reign | fl. circa 2600 BCE |

| Predecessor | Meskalamdug |

| Successor | A'annepada |

| House | First Dynasty of Ur |

Filiation

The "Treasure of Ur" discovered in Mari

Mesannepada was a son of Meskalamdug.[10] A lapis-lazuli bead with the name of King Meskalamdug was found in Mari, in the so-called "Treasure of Ur", and reads:[11][12][13]

𒀭𒈗𒌦 / 𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 / 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠 / 𒌉𒈩𒌦𒄭 / 𒈗𒆧𒆠 / 𒀀 𒈬𒈾𒊒

dlugal-kalam / mes-an-ne2-pa3-da / lugal uri5ki / dumu mes-ug-du10 / lugal kishki / a munaru

"To god Lugalkalam ("the Lord of the Land", identified with Dagan or Enlil), Mesannepada, king of Ur, son of Meskalamdug, king of Kish, has consecrated this bead""

The lapis lazuli bead from Mari, National Museum of Damascus, Syria ("King of Ur", 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠 side).[18][19][20]

The lapis lazuli bead from Mari, National Museum of Damascus, Syria ("King of Ur", 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠 side).[18][19][20] Transcription of the Mari bead.[21]

Transcription of the Mari bead.[21]

Initially, it was thought that this bead (reference M. 4439) referred to a gift by Mesannepada to a king of Mari named Gansud or Ansud.[22][23] This has now been corrected with the translation given above.[11][12] The God "Lugal-kalam" (𒀭𒈗𒌦, "Lord of the Land") to whom the dedication is made, is otherwise known in a dedication by a local ruler Šaba (Šalim) of Mari, also as Lugal-kalam, or in the dedication of Ishtup-Ilum where he is named "Lugal-mātim" (𒀭𒈗𒈤𒁴, "Lord of the Land"), and is considered identical with the local deity Dagan, or Enlil.[24]

It is unclear how this bead came to be in Mari, but this points to some kind of relation between Ur and Mari at that time.[25] The bead was discovered in a jar containing other objects from Ur or Kish, the so-called "Treasure of Ur".[26][27] The jar was recognized as an offering for the foundation of a temple in Mari.[28] Similar dedication beads have also been found from later rulers, such as Shulgi who engraved two carnelian beads with dedication to his gods circa 2100 BCE.[29]

A'annepada dedication tablet

.jpg)

Several dedication tablets by "A'annepada, son of Mesannepada" for the god Ninhursag are also known, which all have similar content:[32][31]

𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄯𒊕 / 𒀀𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 / 𒈗𒌶𒆠 / 𒌉𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 / 𒈗𒌶𒆠 /𒀭𒊩𒌆𒉺𒂅𒊏 / 𒂍 𒈬𒈾𒆕

Dnin-hur-sag / a-an-ne2-pa3-da / lugal uri5{ki} / dumu mes-an-ne2-pa3-da / lugal uri5{ki} /Dnin-hur-sag-ra / e2 mu-na-du3

"For Nin-hursag: A'annepada, king of Ur, son of Mesannepada, king of Ur, built the temple for Ninhursag."

Sumerian King List

.jpg)

Mesannepada appears in the Sumerian King List, as the first ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur, and is credited with a reign of 80 years. His successors are also named:

"... Uruk with weapons was struck down, the kingship to Ur was carried off. In Ur Mesannepada was king, 80 years he ruled; Meskiagnun, son of Mesannepada, was king, 36 years he ruled; Elulu, 25 years he ruled; Balulu, 36 years he ruled; 4 kings, the years: 171(?) they ruled. Ur with weapons was struck down; the kingship to Awan was carried off.

Old Babylonian tablet: the Tummal Chronicle

Mesannepada and his other son are also mentioned in an Old Babylonian tablet (1900-1600 BCE), the Tummal Inscription, relating the accomplishments of several kings. Such tablets are usually copies of older tablets, now lost:

"En-me-barage-si, the king, built the Iri-nanam in Enlil's temple. Aga, son of En-me-barage-si, made the Tummal flourish and brought Ninlil into the Tummal. Then the Tummal fell into ruins for the first time. Meš-Ane-pada built the Bur-šušua in Enlil's temple. Meskiagnun, son of Meš-Ane-pada, made the Tummal flourish and brought Ninlil into the Tummal."

Reign

Mesannepada is associated with an expansion of Ur, at least diplomatically.[36][37] A lapis-lazuli bead in the name of Mesannepada was found in Mari, and formed part of the "Treasure of Ur", made for the dedication of a temple in Mari. Seals from the royal cemetery at Ur have also been found bearing the names of Mesannepada and his predecessors Meskalamdug and Akalamdug, along with Queen Puabi. A seal impression in the name of "Mesannepada, king of Kish" was found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur.[3]

Mesannepada, and his son and successor Meskiagnun, who reigned 36 years,[6] are both named on the Tummal Inscription as upkeepers of the main temple in Nippur along with Gilgamesh of Uruk and his son Ur-Nungal, verifying their status as overlords of Sumer. Judging from the inscriptions, Mesannepada then assumed the title "King of Kish",[7] to indicate his hegemony.[44] In the tablet to the goddess Ninhursag, found in Tell el-Obeid, has the words "A-Anne-pada king of Ur, son of Mes-Anne-pada king of Ur, has built a temple for Ninhursag.[6] Truly it's impossible which a king inherit a throne in his childhood and reign thereafter for 80 years.[6] The reason will be accepted because the length of the son's reign added to the father.[6]

Another son of Mesannepada, named Aannepadda, (Aja-ane-pada or A-Anne-pada, "father chosen by An"), whose years of reigned are unknown,[6] is known for having the temple of Ninhursag constructed (at modern Ubaid) near el-Obed, though he is not named on the kinglist.[5]

Ur-Nammu's structure probably was built on top of a smaller ziggurat which may have been as old as the time of Mes-Anne-pada.[45]

In the 1950s, Edmund I. Gordon conjectured that Mesannepada, and an archaeologically attested early "king of Kish", Mesilim, were one and the same, as their names were interchanged in certain proverbs in later Babylonian tablets; however this has not proved conclusive. More recent scholars tend to regard them as distinct, usually placing Mesilim in Kish before Mesannepada.[46]

.jpg) Mesannepada seal (combat scene)

Mesannepada seal (combat scene).jpg) Mesannepada seal (human wheel scene)

Mesannepada seal (human wheel scene)

Royal Cemetery of Ur

Mesannapeda may have his tomb in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. It has been suggested his tomb could be tomb PG 1232, or PG 1237, nicknamed "the Great Death-Pit".[47]

_(14580860309).jpg) Remains in tomb PG 1232

Remains in tomb PG 1232_(14580870389).jpg) Disposition of royal attendants in tomb PG 1237

Disposition of royal attendants in tomb PG 1237 Ram in a Thicket in PG 1237

Ram in a Thicket in PG 1237 Silver lyre, PG 1237

Silver lyre, PG 1237

References

- For a modern photograph: Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. 1998. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3.

- Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 312.

- Image of a Mesanepada seal in: Legrain, Léon (1936). UR EXCAVATIONS VOLUME III ARCHAIC SEAL-IMPRESSIONS (PDF). THE TRUSTEES OF THE TWO MUSEUMS BY THE AID OF A GRANT FROM THE CARNEGIE CORPORATION OF NEW YORK. p. 44 seal 518 for description, Plate 30, seal 518 for image.

- For a modern photograph: Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. 1998. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3.

- Romano García, Vicente (1965). Ur, Asur y Babilonia. Tres milenios de cultura en Mesopotamia. Madrid: Ediciones Castilla. p. 33.

- Finegan 2015, p. 33, Mesopotamian Beginnings.

- Katz 1993, p. 16.

- Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 312.

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- Description with photograph: Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- Orientalia: Vol. 73. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 183.

- For the discovery of the "Treasure of Ur" and detailed content of the jar, see: Parrot, André (1965). "Les Fouilles de Mari". Syria. Archéologie, Art et Histoire. 42 (3): 197–225. doi:10.3406/syria.1965.5808.

- Orientalia: Vol. 73. Gregorian Biblical BookShop.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- "Mission archéologique de Mari" volume 4, p. 44, fig. 35 (photo); p. 53, fig. 36

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- Object at time of discovery

- Malamat, Abraham (1971). "Mari". The Biblical Archaeologist. 34 (1): 4. doi:10.2307/3210950. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210950.

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- Parrot, André (1965). "Les Fouilles de Mari". Syria: 220.

- orientalia Vol.38. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 358.

- Orientalia: Vol. 73. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 322.

- orientalia Vol.38. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 358.

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to ... Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. pp. 139–145. ISBN 9781588390431.

- Matthews, Donald M. (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. Saint-Paul. p. 108. ISBN 978-3-525-53896-8.

- Spycket, Agnès (1981). Handbuch der Orientalistik (in French). BRILL. p. 80. ISBN 978-90-04-06248-1.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "British Museum, tablet".

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Sollberger, Edmond (1962). "The Tummal Inscription". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 16 (2): 40–47. doi:10.2307/1359332. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359332.

- Matthews 1997, p. 1, Introduction.

- Matthews 1997, p. 2, Introduction.

- Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 312.

- Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 312.

- MAEDA, TOHRU (1981). "KING OF KISH" IN PRE-SARGONIC SUMER. Orient: The Reports of the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan, Volume 17. p. 8.

- Orientalia: Vol. 73. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 176.

- "Cylinder Seal - B16852 Collections - Penn Museum". www.penn.museum.

- Finegan, Jack (2019). Archaeological History Of The Ancient Middle East. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-429-72638-5.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). "History: Heroes, Kings and Ensi's". The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780226452388.

- Finegan 2015, p. 43, Mesopotamian Beginnings.

- Finegan, Jack (2019). Archaeological History Of The Ancient Middle East. Routledge. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-429-72638-5.

- Reade, Julian (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

Bibliography

- Finegan, Jack (2015). Light from the Ancient Past: The Archaeological Background of the Hebrew-Christian Religion. 1. Princeton University Press. p. 652. ISBN 9781400875153.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katz, Dina (1993). Gilgamesh and Akka. Brill Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9789072371676.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Matthews, Donald M. (1997). The Early Glyptic of Tell Brak: Cylinder Seals of Third Millennium Syria. Saint-Paul. p. 311. ISBN 9783525538968.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lugal-kitun of Uruk |

King of Sumer ca. 26th century BC |

Succeeded by A'annepada |

| Preceded by Meskalamdug |

Ensí of Ur ca. 26th century BC | |

.jpg)