Lady Zhen

Lady Zhen (26 January 183[1] – 4 August 221[2][3]), personal name unknown, was the first wife of Cao Pi, the first ruler of the state of Cao Wei in the Three Kingdoms period. In 226, she was posthumously honoured as Empress Wenzhao when her son, Cao Rui, succeeded Cao Pi as the emperor of Wei.

| Lady Zhen 甄夫人 / 甄氏 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

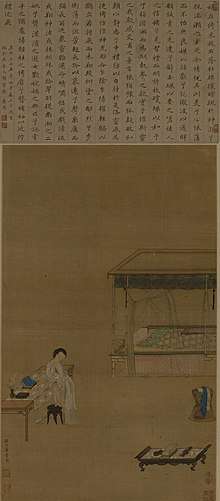

A Qing dynasty illustration of Lady Zhen | |||||

| Born | 26 January 183[lower-alpha 1] Wuji County, Hebei | ||||

| Died | 4 August 221 (aged 38)[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] Handan, Hebei | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Father | Zhen Yi | ||||

| Mother | Lady Zhang | ||||

Early life

Lady Zhen was from Wuji County (無極縣), Zhongshan Commandery (中山郡), which is in present-day Wuji County, Hebei. She was a descendant of Zhen Han (甄邯), who served as a Grand Protector (太保) in the late Western Han dynasty and later the General-in-Chief (大將軍) during the short-lived Xin dynasty. Her father, Zhen Yi (甄逸), served as the Prefect of Shangcai County in the late Eastern Han dynasty. He died when Lady Zhen was about three years old.[4] Lady Zhen's mother, whose maiden family name was Zhang (張), was from Changshan Commandery (常山郡; around present-day Zhengding County, Hebei). Lady Zhen's parents had three sons and five daughters: eldest son Zhen Yu (甄豫), who died early; second son Zhen Yan (甄儼), who became a xiaolian and later served as an assistant to the General-in-Chief and as the Chief of Quliang County; third son Zhen Yao (甄堯), who was also a xiaolian; eldest daughter Zhen Jiang (甄姜); second daughter Zhen Tuo (甄脫); third daughter Zhen Dao (甄道); fourth daughter Zhen Rong (甄榮). Lady Zhen was the youngest of the five daughters.[5]

Zhen Yi once brought his children to meet Liu Liang (劉良), a fortune teller, who commented on Lady Zhen, "This girl will become very noble in the future." Unlike many children of her age, the young Lady Zhen did not enjoy playing. Once, when she was eight years old, her sisters went to the balcony to watch a group of horse-riding performers outside their house but Lady Zhen did not join in. Her sisters were puzzled so they asked her, and she responded, "Is this something a girl should watch?" When she was nine years old, she became interested in scholarly arts and started reading books and using her brothers' writing materials. Her brothers told her, "You should be learning what women traditionally do (such as weaving). When you picked up reading, were you thinking of becoming a female academician?" Lady Zhen replied, "I heard that virtuous women in history learnt from the successes and failures of those who lived before them. If they didn't read, how did they learn all that?"[6]

Towards the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, after the death of Emperor Ling, China entered a chaotic period because the central government's authority weakened, and regional officials and warlords started fighting each other in a bid to gain supremacy. The common people suffered from poverty and hunger, and many wealthy households who owned expensive items such as jewellery offered to sell these valuables in return for food. Lady Zhen's family had large stockpiles of grain, and they planned to take advantage of the situation to sell their grain in exchange for valuable items. Lady Zhen, who about 10 years old at the time, said to her mother, "It's not wrong to own expensive items, but in this chaotic era, owning such items has become a wrongdoing. Our neighbours are suffering from hunger, so why don't we distribute our surplus grain to our fellow townsfolk? This is an act of graciousness and kindness." Her family praised her for her suggestion and heeded her advice.[7]

When Lady Zhen was 14, her second brother Zhen Yan (甄儼) died, and she was deeply grieved. She continued to show respect towards Zhen Yan's widow, and even helped to raise Zhen Yan's son. Lady Zhen's mother was particularly strict towards her daughters-in-law and treated them harshly. Lady Zhen told her mother, "It's unfortunate that Second Brother died early. Second Sister-in-Law became widowed at such a young age and she's now left with only her son. You should treat your daughters-in-law better and love them as you would love your own daughters." Lady Zhen's mother was so deeply touched that she cried, and she started treating her daughters-in-law better and allowed them to accompany and wait on her.[8]

Marriages to Yuan Xi and Cao Pi

Sometime in the middle of the Jian'an era (196–220) of the reign of Emperor Xian, Lady Zhen married Yuan Xi, the second son of Yuan Shao, a warlord who controlled much of northern China. Yuan Shao later put Yuan Xi in charge of You Province, so Yuan Xi left to assume his appointment. Lady Zhen did not follow her husband and remained in Ye (in present-day Handan, Hebei), the administrative centre of Yuan Shao's domain, to take care of her mother-in-law.[9]

Yuan Shao lost to his rival, Cao Cao, at the Battle of Guandu in 200 CE and died two years later. After his death, his sons Yuan Tan and Yuan Shang became embroiled in internecine struggles over their father's vast domain. When the Yuan brothers were exhausted from their wars against each other, Cao Cao attacked and defeated them, swiftly conquering the territories that used to be controlled by the Yuans. In 204, Cao Cao defeated Yuan Shang at the Battle of Ye and his forces occupied the city. Cao Cao's son, Cao Pi, entered Yuan Shao's residence and met Lady Liu (Yuan Shao's widow) and Lady Zhen. Lady Zhen was so terrified that she buried her face in her mother-in-law's lap. Cao Pi said, "What's going on, Madam Liu? Ask that lady to lift up her head!" Cao Pi was very impressed and entranced by Lady Zhen's beauty when he saw her. His father allowed him to marry her later.[10] Another account of this incident stated that Lady Liu and Lady Zhen were in Yuan Shang's residence when Cao Pi entered. Lady Zhen's hair was dishevelled and she was crying behind her mother-in-law. When Cao Pi asked, Lady Liu told him the woman behind her was Yuan Xi's wife. Cao Pi was so entranced by Lady Zhen's beauty that he married her and treated her well.[11] Yuan Xi was still alive at the time. Yuan Shang came to join him after his defeat by Cao Cao. In 207, Cao Cao defeated Yuan Xi, Yuan Shang and their Wuhuan allies at the Battle of White Wolf Mountain, after which they fled to Liaodong to join the warlord Gongsun Kang. Gongsun Kang feared that they would become a threat to him, so he lured them into a trap, executed them, and sent their heads to Cao Cao.[12]

As Cao Pi's wife

Lady Zhen bore Cao Pi a son and a daughter. Their son, Cao Rui, later became the second emperor of the state of Cao Wei in the Three Kingdoms period. Their daughter, whose personal name was not recorded in history, was referred to as "Princess Dongxiang" (東鄉公主; literally "Princess of the East District") in historical records.[13] Lady Zhen remained humble even though Cao Pi deeply fancied her. She provided encouragement to Cao Pi's other wives who were also adored by him, and comforted those whom he less favoured. She also often urged Cao Pi to take more concubines so that he would have more descendants, citing the example of the mythical Yellow Emperor. Cao Pi was very pleased. Once, Cao Pi wanted to send Lady Ren (任氏), one of his concubines who fell out favour with him, back to her family – which meant that he was divorcing her. When Lady Zhen heard about it, she told her husband, "Lady Ren comes from a reputable clan. I can't match her in terms of moral character and looks. Why do you want to send her away?" Cao Pi replied, "She is unruly, impulsive and disobedient. She has made me angry many times before. I'm sending her away." Lady Zhen wept and pleaded with her husband, "Everyone knows that you love and adore me, and they'll think that you're sending Lady Ren away because of me. I fear that I'll be ridiculed and accused of abusing your favour towards me. Please consider your decision again carefully." Cao Pi ignored her and sent Lady Ren away.[14]

In 211, Cao Cao embarked on a campaign to attack a coalition of northwestern warlords led by Ma Chao and Han Sui, leading to the Battle of Tong Pass and the subsequent battles. Cao Cao's wife Lady Bian followed her husband and stayed at Meng Ford (孟津; present-day Mengjin County, Henan), while Cao Pi remained in Ye (in present-day Handan, Hebei). Lady Bian fell ill during that time. Lady Zhen became worried when she heard about it and she cried day and night. She constantly sent messengers to inquire her mother-in-law's condition, but refused to believe them when they reported that Lady Bian was getting better, and she became filled with greater anxiety. Lady Bian later wrote a letter to her, telling her that she had fully recovered, and only then did Lady Zhen's worries disappear. About a year later, when Lady Bian returned to Ye, Lady Zhen rushed to see her mother-in-law and displayed mixed expressions of sadness and joy. Those who were present were all deeply moved by the scene before them. Lady Bian assured Lady Zhen that her illness was not serious and praised her for her filial piety.[15]

In 216, Cao Cao launched another campaign to attack the southeastern warlord Sun Quan, leading to the Battle of Ruxu in 217. Lady Bian, Cao Pi, Cao Rui and Princess Dongxiang all followed Cao Cao on the campaign, but Lady Zhen remained in Ye because she was sick. When Cao Pi and Lady Zhen's children returned to Ye in late 217 after the campaign, Lady Bian's attendants were surprised to see that Lady Zhen was very cheerful. They asked, "Lady, you've not seen your children for about a year. We thought you would miss them and be worried about them, but yet you're so optimistic. Why is that so?" Lady Zhen laughed and replied, "Why should I be worried when (Cao) Rui and the others are with Madam (Lady Bian)?"[16]

Death

After Cao Cao died in early 220, his vassal king title – "King of Wei" (魏王) – was inherited by Cao Pi. Later that year, Cao Pi forced Emperor Xian, whom he paid nominal allegiance to, to abdicate in his favour, effectively ending the Han dynasty. Cao Pi became the emperor and established the state of Cao Wei, which marked the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period. The dethroned Emperor Xian was reduced to the status of a duke – the Duke of Shanyang (山陽公). The former emperor presented his two daughters to Cao Pi to be his concubines. Cao Pi began to favour his other concubines, especially Guo Nüwang. When Lady Zhen realised that Cao Pi favoured her less, she started complaining. Cao Pi was furious when he heard about it. On 4 August 221,[lower-alpha 2] he sent an emissary to Ye (in present-day Handan, Hebei) to execute Lady Zhen by forcing her to take her own life. Lady Zhen was buried in Ye on 20 March 227.[17]

Lady Zhen's downfall was due to Guo Nüwang, whom Cao Pi fancied. One year after Lady Zhen's death, Cao Pi instated Guo as the empress despite opposition from an official, Zhan Qian (棧潛).[18] The historical text Han Jin Chunqiu (漢晉春秋) mentioned that Lady Zhen's body was desecrated after her death – her face was covered by her hair and rice husks were stuffed into her mouth. Cao Rui was raised by Guo Nüwang after Lady Zhen's death.[19]

Alternative account of Lady Zhen's death

The Wei Shu (魏書) mentioned that Cao Pi issued an edict to Lady Zhen, asking her to move to the newly constructed Changqiu Palace (長秋宮) in Luoyang. Lady Zhen declined humbly, stating that she felt that she was not capable enough to manage the imperial harem, and also because she was ill. Cao Pi then consecutively sent another two edicts but Lady Zhen rejected both. It was around summer at the time. Cao Pi intended to fetch Lady Zhen from Ye to Luoyang in autumn, when the weather was cooler. However, Lady Zhen died of illness in Ye a few months later. Cao Pi mourned her death and posthumously elevated her to the status of an empress.[20]

Pei Songzhi, who added the Wei Shu account to Lady Zhen's biography in the Sanguozhi, found the account dubious. He believed that there were specific reasons as to why Cao Pi did not instate Lady Zhen as the empress after he became the emperor, and why he forced her to commit suicide. He suspected that Lady Zhen had probably committed an offence, which was not recorded in the official histories of the Cao Wei state.[21]

Alternative theories on Lady Zhen's death

Many popular stories speculated that the reason for Lady Zhen's death was that she had a secret affair with Cao Pi's younger brother, Cao Zhi, even though this speculation is not supported by evidence and is improbable.[22] Some more fantastical accounts alleged that she had an affair with Cao Cao as well; one example of this can be found in the A New Account of the Tales of the World, in which Cao Cao started the Battle of Ye in 204 to obtain Lady Zhen.[23]

Posthumous honours

Cao Pi died on 29 June 226 and was succeeded by Cao Rui, who became the second ruler of Cao Wei. On 25 July 226, Cao Rui granted his mother the posthumous title "Empress Wenzhao", which literally means "cultured and diligent empress". Lady Zhen's family and relatives also received noble titles.[24]

The historical text Han Jin Chunqiu mentioned that Cao Rui had all along been aware of his mother's fate, and he was angry and sad about it. After he became emperor, his stepmother Guo Nüwang became the empress dowager. When he asked her about how his mother died, Guo replied, "The Late Emperor was the one who ordered her death, so why are you asking me? You're your father's son so you can blame your dead father. Are you going to kill your stepmother for your real mother?" Cao Rui turned furious and forced Empress Dowager Guo to commit suicide. He had her buried with the funeral rites befitting that of an empress, but also ordered her dead body to be treated in the same manner as she did to his mother – hair covering face, mouth stuffed with rice husks.[25] However, the historical text Weilüe stated that after Empress Dowager Guo died of illness in 235, Cao Pi's concubine Lady Li (李夫人) told Cao Rui about the fate of his mother. Cao Rui was deeply grieved and he ordered Guo's dead body to be treated in the same manner as she did to his mother.[26]

Reliability of alternative historical sources on Lady Zhen's life

The authoritative historical source on Lady Zhen's life is the Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi), which was written by Chen Shou in the third century. In the fifth century, Pei Songzhi annotated the Sanguozhi by incorporating information from other texts and adding his personal commentary. Some sources used in the annotations include: Wei Shu (Book of Wei), by Wang Chen, Xun Yi and Ruan Ji; Weilüe (Brief History of Wei), by Yu Huan. The original version of Lady Zhen's biography in the Sanguozhi did not contain the anecdotes about Zhen's excellent moral conduct, such as her care for her family members, her filial piety towards her mother-in-law Lady Bian, her tolerance of Cao Pi's other wives, etc. These accounts, which were mostly documented in the Wei Shu and the Weilüe, were later added to the Sanguozhi by Pei Songzhi. In his commentary, Pei cast doubts on the anecdotes relating to the "virtuous deeds" of Lady Zhen and other noble ladies of Wei, because it was difficult to verify whether they were true or not due to a dearth of alternative sources. The Wei Shu and the Weilüe were among the official histories of Wei, so they were likely to be biased towards Lady Zhen, hence some of those anecdotes might have been fabricated by Wei historians to promote a positive image of Lady Zhen. Pei remarked that Chen Shou had done well in omitting the questionable information when he first compiled the Sanguozhi.[27]

Personal name

Lady Zhen's personal name was not recorded in any surviving historical text. All near-contemporary sources, such as Chen Shou's Sanguozhi and Xi Zuochi's Han Jin Chunqiu, refer to her as "Lady Zhen" (甄氏), "Madam Zhen" (甄夫人), "Empress Zhen" (甄后), or simply "(the) Empress" (后).

The attachment of the names "Fu" (宓; Fú) and "Luo" (洛; Luò) to Lady Zhen came about due to the legend of a romance between her and Cao Zhi, which Robert Joe Cutter, a specialist in research on Cao Zhi, concludes to be "a piece of anecdotal fiction inspired by the [Luo Shen Fu (洛神賦; Rhapsody on the Goddess of the Luo)] and taking advantage of the possibilities inherent in a triangle involving a beautiful lady, an emperor, and his romanticised brother."[28]

A tradition dating back to at least as far as an undated, anonymous note edited into the Tang dynasty writer Li Shan's annotated Wen Xuan had Cao Zhi meeting the ghost of the recently deceased Empress Zhen, and writing a poem originally titled Gan Zhen Fu (感甄賦; Rhapsody on Being Moved by Lady Zhen). Afterwards, Cao Rui found this poem about his uncle's love for his mother, and changed the title to Luo Shen Fu (洛神賦), which could be translated as Rhapsody on the Goddess of the Luo or Rhapsody on the Divine Luo, this second interpretation presumably referencing Lady Zhen's personal name, Luo.[29] If true, this would be a forename unique to early China, as the Chinese character '洛' has been a toponym since it entered the language.

The poem contains references to the spirit of the Luo River, named Consort Fu (宓妃), interpreted as a proxy for Empress Zhen by those who believed in Cao Zhi's infatuation with her. This interpretation becomes less allusive if Empress Zhen's personal name was actually "Fu".

In popular culture

Lady Zhen is featured as a playable character in Koei's Dynasty Warriors and Warriors Orochi video game series. She is referred to as "Zhen Ji" (literally means "Consort Zhen" or "Lady Zhen" in Chinese) in the games. Though, like every female character in the franchise, the space between her name was removed from Dynasty Warriors Next and Warriors Orochi 3 onward.

Miu Kam-fung portrayed Zhen Fu (Lady Zhen) in the 1975 Hong Kong television series God of River Lok produced by TVB, which features the romance between Lady Zhen and Cao Zhi. In 2002, TVB produced a similar television series titled Where the Legend Begins, starring Ada Choi as Lady Zhen. There is also a 2013 Chinese television series Legend of Goddess Luo (新洛神) produced by Huace Film and TV, starring Li Yixiao as Lady Zhen. The 2018 Chinese television series Hello Dear Ancestors (亲爱的活祖宗) has a time travelling theme, starring Wang Ting as Zhen Fu and her lookalike in modern times.

Notes

- The Wei Shu mentioned that Lady Zhen was born on the dingyou day of the 12th lunar month in the fifth year of the Guanghe era (178–184) in the reign of Emperor Ling of the Eastern Han dynasty.[1] This date corresponds to 26 January 183 in the Gregorian calendar.

- Cao Pi's biography in the Sanguozhi mentioned that Lady Zhen died on the dingmao day of the 6th month of the 2nd year of the Huangchu era (220–226) in Cao Pi's reign.[2] This date corresponds to 4 August 221 in the Gregorian calendar.

- An annotation from the Wei Shu in Lady Zhen's biography in the Sanguozhi confirms Zhen's death date as stated in Cao Pi's biography.[3]

References

- (魏書曰: ... 后以漢光和五年十二月丁酉生。) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- ([黃初二年六月]丁卯,夫人甄氏卒。) Sanguozhi vol. 2.

- (會后疾遂篤,夏六月丁卯,崩于鄴。) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (文昭甄皇后,中山無極人,明帝母,漢太保甄邯後也,世吏二千石。父逸,上蔡令。后三歲失父。) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (魏書曰:逸娶常山張氏,生三男五女:長男豫,早終;次儼,舉孝廉,大將軍掾、曲梁長;次堯,舉孝廉;長女姜,次脫,次道,次榮,次即后。) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (後相者劉良相后及諸子,良指后曰:「此女貴乃不可言。」 ... 后自少至長,不好戲弄。年八歲,外有立騎馬戲者,家人諸姊皆上閣觀之,后獨不行。諸姊怪問之,后荅言:「此豈女人之所觀邪?」年九歲,喜書,視字輙識,數用諸兄筆硯,兄謂后言:「汝當習女工。用書為學,當作女博士邪?」后荅言:「聞古者賢女,未有不學前世成敗,以為己誡。不知書,何由見之?」) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (後天下兵亂,加以饑饉,百姓皆賣金銀珠玉寶物,時后家大有儲穀,頗以買之。后年十餘歲,白母曰:「今世亂而多買寶物,匹夫無罪,懷璧為罪。又左右皆饑乏,不如以穀振給親族鄰里,廣為恩惠也。」舉家稱善,即從后言。) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (魏略曰:后年十四,喪中兄儼,悲哀過制,事寡嫂謙敬,事處其勞,拊養儼子,慈愛甚篤。后母性嚴,待諸婦有常,后數諫母:「兄不幸早終,嫂年少守節,顧留一子,以大義言之,待之當如婦,愛之宜如女。」母感后言流涕,便令后與嫂共止,寢息坐起常相隨,恩愛益密。) Weilüe annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (建安中,袁紹為中子熈納之。熈出為幽州,后留養姑。) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (魏略曰:熈出在幽州,后留侍姑。及鄴城破,紹妻及后共坐皇堂上。文帝入紹舍,見紹妻及后,后怖,以頭伏姑膝上,紹妻兩手自搏。文帝謂曰:「劉夫人云何如此?令新婦舉頭!」姑乃捧后令仰,文帝就視,見其顏色非凡,稱歎之。太祖聞其意,遂為迎取。) Weilüe annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (世語曰:太祖下鄴,文帝先入袁尚府,有婦人被髮垢靣,垂涕立紹妻劉後,文帝問之,劉荅「是熈妻」,顧擥髮髻,以巾拭面,姿貌絕倫。旣過,劉謂后「不憂死矣」!遂見納,有寵。) Shiyu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- ([建安]十二年,太祖至遼西擊烏丸。尚、熈與烏丸逆軍戰,敗走奔遼東,公孫康誘斬之,送其首。) Sanguozhi vol. 6.

- (及兾州平,文帝納后於鄴,有寵,生明帝及東鄉公主。) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (魏書曰:后寵愈隆而彌自挹損,後宮有寵者勸勉之,其無寵者慰誨之,每因閑宴,常勸帝,言「昔黃帝子孫蕃育,蓋由妾媵衆多,乃獲斯祚耳。所願廣求淑媛,以豐繼嗣。」帝心嘉焉。其後帝欲遣任氏,后請於帝曰:「任旣鄉黨名族,德、色,妾等不及也,如何遣之?」帝曰:「任性狷急不婉順,前後忿吾非一,是以遣之耳。」后流涕固請曰:「妾受敬遇之恩,衆人所知,必謂任之出,是妾之由。上懼有見私之譏,下受專寵之罪,願重留意!」帝不聽,遂出之。) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (十六年十月,太祖征關中,武宣皇后從,留孟津,帝居守鄴。時武宣皇后體小不安,后不得定省,憂怖,晝夜泣涕;左右驟以差問告,后猶不信,曰:「夫人在家,故疾每動,輙歷時,今疾便差,何速也?此欲慰我意耳!」憂愈甚。後得武宣皇后還書,說疾已平復,后乃懽恱。十七年正月,大軍還鄴,后朝武宣皇后,望幄座悲喜,感動左右。武宣皇后見后如此,亦泣,且謂之曰:「新婦謂吾前病如昔時困邪?吾時小小耳,十餘日即差,不當視我顏色乎!」嘆嗟曰:「此真孝婦也。」) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (二十一年,太祖東征,武宣皇后、文帝及明帝、東鄉公主皆從,時后以病留鄴。二十二年九月,大軍還,武宣皇后左右侍御見后顏色豐盈,怪問之曰:「后與二子別乆,下流之情,不可為念,而后顏色更盛,何也?」后笑荅之曰:「叡等自隨夫人,我當何憂!」后之賢明以禮自持如此。) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (延康元年正月,文帝即王位,六月,南征,后留鄴。黃初元年十月,帝踐阼。踐阼之後,山陽公奉二女以嬪于魏,郭后、李、陰貴人並愛幸,后愈失意,有怨言。帝大怒,二年六月,遣使賜死,葬于鄴。) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (甄后之死,由后之寵也。黃初三年,將登后位,文帝欲立為后,中郎棧潛上疏曰: ... 文帝不從,遂立為皇后。) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (漢晉春秋曰:初,甄后之誅,由郭后之寵,及殯,令被髮覆面,以糠塞口,遂立郭后,使養明帝。) Han Jin Chunqiu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (魏書曰:有司奏建長秋宮,帝璽書迎后,詣行在所,后上表曰:「妾聞先代之興,所以饗國乆長,垂祚後嗣,無不由后妃焉。故必審選其人,以興內教。令踐阼之初,誠宜登進賢淑,統理六宮。妾自省愚陋,不任粢盛之事,加以寢疾,敢守微志。」璽書三至而后三讓,言甚懇切。時盛暑,帝欲須秋涼乃更迎后。會后疾遂篤,夏六月丁卯,崩于鄴。帝哀痛咨嗟,策贈皇后璽綬。) Wei Shu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (臣松之以為春秋之義,內大惡諱,小惡不書。文帝之不立甄氏,及加殺害,事有明審。魏史若以為大惡邪,則宜隱而不言,若謂為小惡邪,則不應假為之辭,而崇飾虛文乃至於是,異乎所聞於舊史。) Pei Songzhi's annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. "A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD)".

- Yiqing, Liu. A New Account of the Tales of the World. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Press, 2002. 763. Print.

- (明帝即位,有司奏請追謚,使司空王朗持節奉策以太牢告祠于陵,又別立寢廟。 ...) Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (漢晉春秋曰: ... 帝知之,心常懷忿,數泣問甄后死狀。郭后曰:「先帝自殺,何以責問我?且汝為人子,可追讎死父,為前母枉殺後母邪?」明帝怒,遂逼殺之,勑殯者使如甄后故事。) Han Jin Chunqiu annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (魏略曰:明帝旣嗣立,追痛甄后之薨,故太后以憂暴崩。甄后臨沒,以帝屬李夫人。及太后崩,夫人乃說甄后見譖之禍,不獲大斂,被髮覆靣,帝哀恨流涕,命殯葬太后,皆如甄后故事。) Weilüe annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- (推此而言,其稱卞、甄諸后言行之善,皆難以實論。陳氏刪落,良有以也。) Pei Songzhi's annotation in Sanguozhi vol. 5.

- Cutter, Robert Joe (1983). "Cao Zhi (192–232) and His Poetry, PhD Diss". Tacoma: University of Washington: 287. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help), cited in Cutter, Robert Joe (October–December 1992). "The Death of Empress Zhen: Fiction and Historiography in Early Medieval China". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 112 (4): 577–583. JSTOR 604472. - Xiao, Tong; Li, Shan, eds. (1977) [531]. "卷 19.11–12". Wen Xuan. Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing. pp. 269–270.

- Chen, Shou (3rd century). Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi).

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms 23-220 AD. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004156050.

- Pei, Songzhi (5th century). Annotations to Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi zhu).

- Sima, Guang (1084). Zizhi Tongjian.