Gao You

Gao You (c. 168–212) was a Chinese scholar and bureaucrat during Eastern Han dynasty under its last emperor and the warlord Cao Cao.

| Gao You | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 高誘 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 高诱 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Life

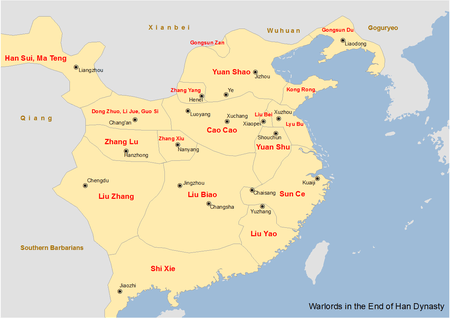

Gao You was born in Zhuo Commandery (涿郡, Zhuōjùn; present-day Zhuozhou, Hebei)[1] around AD 168.[2] He studied with one of the area's preëminent scholars at the time, Lu Zhi.[3] Lu was known for his work with texts concerning Chinese rituals and for his assistance in compiling the History of the Eastern Han (t 東觀漢記, s 东观汉记, Dōngguān Hànjì).[1] His other students included Liu Bei, the future king of Shu, and Gongsun Zan, another regional warlord of the era.[4] Gao's schooling was interrupted by the Yellow Turban Rebellion in AD 184.[5]

Gao was working in Xuchang in the Capital Construction Office in AD 205 when he received his first post as magistrate of Puyang in the Eastern Commandery (t 東郡, s 东郡, Dōngjùn).[5] This was about 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) south of the location of the present county-level city of Puyang in Henan.[6] He later held some other mid-level appointments under Cao Cao,[3] who ruled northern China in the name of the Han emperor until his death in 220.

Gao died in AD 212.[2]

Works

Gao's work dates mostly to the Jian'an Era (AD 196–220) of the Xian Emperor,[7] the last emperor of the Eastern Han dynasty. Gao wrote commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals ordered by Lü Buwei;[3] the Classics of Filial Piety[8] and of Mountains and Seas;[9] the Huainanzi;[3][1] The Strategies of the Warring States;[3][1][10] Discourse Weighed in the Balance;[9] and the collected works of the philosopher Mencius.[11]

Gao began his Notes on the Huainanzi (《淮南子注》, Huáinánzi Zhù)[12] while studying under Lu[1] and then completed his full commentary[12] in AD 212.[13] The Huainanzi had become important by his time because it was used to "verify" or "test" the genuineness of editions and commentaries of other classics.[14] Charles Le Blanc argues that the phrasing of Gao's preface to his edition of the Huainanzi indicates that still had notes from his former teacher to consult; he also argues that Gao's commentary presumably incorporates the highlights of the otherwise lost work by Lu's own teacher Ma Rong.[15]

By the time he finished his work on the Huainanzi, Gao had also already completed his notes on the Classic of Filial Piety and the collected works of Mencius.[8] The latter is now lost.[1]

Gao wrote his commentary on Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals next, presumably under the influence of Lu's own work on that text. Most of his preface consists of a biography of its chief editor, the Qin chancellor Lü Buwei. This account mostly repeats the biography of Lü found in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. He defends the work's importance—equating it to Liu An's Huainanzi, Yang Xiong's Model Sayings, and the collected works of Xun Kuang and Mencius—by reference to its inclusion in the official bibliographies compiled by Liu Xiang and Liu Xin.[1]

Gao's commentary on the Strategies of the Warring States appears to have been its first. It is now lost, except for the parts that were included in the later Song-era commentary by Yao Hong.[10]

Legacy

Current editions of the Huainanzi derive in part from copies of Gao's commentaries on it. He commented on all 21 chapters of the original text, but only 13 survive in full. Although the authenticity and completeness of the eight chapters now taken from Xu Shen's alleged commentary are both questioned, Gao's chapters are thought to represent survivals of a genuine copy of the original text.[16] The sinologist Victor Mair considers Gao You responsible for the current organization of the Strategies of the Warring States.[17]

Gao's commentaries on the Huainanzi and Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals include numerous asides on the pronunciation of certain characters, particularly in his local dialect.[7] His notes on the Huainanzi also includes material on the peculiarities of the usual dialect in the former area of Chu.[7] Baxter and Sagart have used some of these notes in their reconstruction of the pronunciation of old Chinese.[18]

Gao's note that his copy of Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals, which he considered in "poor condition", consisted of 173,054 characters is significant to scholarship concerning that text, since it makes his edition about a third longer than any currently existing.[1]

References

Citations

- Knoblock & al. (2000), p. 671.

- Bumbacher (2016), p. 650.

- Crespigny (2007).

- Chen Shou, "Biography of the Former Lord", Records of the Three Kingdoms. (in Chinese)

- Roth (1992), p. 41.

- Barbieri-Low & al. (2015), p. 1015.

- Coblin (1983).

- Knoblock & al. (2000), p. 672.

- Theobald (2012), "Gou Mang"

- Theobald (2010), "Zhanguoce".

- Baxter (1992), p. 295.

- Theobald (2010), "Huainanzi".

- Zhang (2012), p. 244.

- Zhao (2013), p. 283.

- Le Blanc (1985), p. 72.

- Le Blanc (1985), p. 75.

- Mair (2000), p. 471.

- Baxter & al. (2014), p. 265.

Bibliography

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J.; et al. (2015), Law, State, and Society in Early Imperial China, Sinica Leidensia, No. 247, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004300538.

- Baxter, William Hubbard III (1992), A Handbook of Old Tibetan phonology, Berlin: Mouton.

- Baxter, William Hubbard III; et al. (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bumbacher, Stephan Peter (2016), "Reconstructing the Zhuang Zi: Preliminary Considerations" (PDF), Asiatische Studien, 70, Zurich: University of Zurich, pp. 611–74, doi:10.5167/uzh-133211.

- Coblin, W. South (1983), "Gao You", A Handbook of Eastern Han Sound Glosses, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, p. 30, ISBN 9789622012585.

- De Crespigny, Rafe (2007), "Gao You", A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Sect. IV: China, Vol. 19, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, p. 246, ISBN 9789047411840.

- Le Blanc, Charles (1985), Huai-nan Tzu: Philosophical Synthesis in Early Han Thought, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, ISBN 9789622091795.

- Lü Buwei & al., 《呂氏春秋》, in Knoblock, John; et al., eds. (2000), The Annals of Lü Buwei, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-3354-6.

- Mair, Victor H., ed. (2000), "Intrigues of the Warring States", The Shorter Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 471–3, ISBN 9780231505628.

- Roth, Harold David (1992), The Textual History of the Huan-nan Tzu, Monographs of the ASA, No. 46, Association for Asian Studies.

- Theobald, Ulrich, China Knowledge, Tübingen.

- Zhang Hanmo (2012), Models of Authorship and Text-making in Early China (PDF), Los Angeles: University of California.

- Zhao Lu (2013), In Pursuit of the Great Peace: Han Dynasty Classicism and the Making of Early Medieval Literati Culture, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.