Ladakh Chronicles

The Ladakh Chronicles, or La-dvags-rgyal-rabs (Tibetan: ལ་དྭགས་རྒྱལ་རབས, Wylie: La dwags rgyal rabs ),[lower-alpha 1] is a historical work that covers the history of Ladakh from the beginnings of the first Tibetan dynasty of Ladakh until the end of the Namgyal dynasty. The chronicles were compiled by the Namgyal dynasty, mostly during the 17th century, and are considered to be the main written source for Ladakhi history.[1]:17[2]:1,3[3]:7

The Ladakh Chronicles are one of only two surviving pre-19th century literary sources from Ladakh. Only seven original manuscripts of the chronicles are known to have existed, of which two survive to the modern day.[2]

History

Until the early 19th century, European historians believed that there were no written histories from Ladakh.[4] After reports about its existence, Alexander Cunningham found the first known manuscript of the chronicles (Ms. Cunningham) during his stay in Ladakh in 1847.[2][4]:87 Cunningham had the manuscript translated into Urdu, but only reproduced part of it in English in his works; Cunningham did not consider the story after the end of the 17th century to be important, so he omitted the remainder from his works.[2]:2

In 1866, Emil Schlagintweit published a study (Die Könige von Tibet) about the Ladakh Chronicles, based on another manuscript (Ms.S.).[2]:1 This was followed by missionary Karl Marx whose studies and translations of a third manuscript (Ms.A.) were published posthumously in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal between 1891 and 1902.[2]:1[3]:77 The first publication of the Ladakh Chronicles' summary of the 1684 Treaty of Tingmosgang appeared as an appendix to a book by Henry Ramsay.[3]:77

In 1926, Tibetologist August Herman Francke published a revised translation and the first detailed history of Ladakh, based on five manuscripts of the chronicles (Ms.S, Ms.A, Ms.B, Ms.C, Ms.L).[3]:77[2]:1[5] Francke's edition then became the standard edition for future studies on the pre-Dogra Ladakhi dynasties.[2]:1 In the later part of the 20th century, research on the Ladakh Chronicles were complemented by further studies by Luciano Petech and Zahiruddin Ahmad.[3]:77[4]

Known manuscripts

There are seven manuscripts of the Ladakh Chronicles that are known to have existed:[2]

- Ms.S Bodleian Library in Oxford, Ms.Tibet, C.7.: This manuscript belonged to the former King of Ladakh and was stored in the library of the sTog palace. The original manuscript has since disappeared, but its contents were copied in 1856 and later published by Emil Schlagintweit.[2]:1

- Ms.A: This manuscript only covers the history up until the reign of Sengge Namgyal (r. 1616–1642).[2]:171–172 The original manuscript no longer survives but its text was partly published and translated by missionary Karl Marx.[2]:1

- Ms.B: This manuscript consists of only four pages about the Namgyal dynasty and its conquest by the Dogra dynasty of Jammu and Kashmir. The original manuscript no longer exists.[2]:1

- Ms.C: This manuscript was compiled at the end of the 19th century by Munshi dPal-rgyas and includes three appendices about the Dogra conquest. The original no longer exists.[2]:1

- Ms.L British Museum, Oriental Collection 6683: This manuscript covers Ladakhi history until the reign of Deldan Namgyal (r. 1642–1694)[2]:171–172 and also contains a plain list of subsequent rulers until the Dogra conquest.[2]:1

- Ms.Cunningham: This manuscript covers the history from the reign of Tsewang Namgyal I (r. 1575–1595) until at least the reign of Delek Namgyal (r. 1680–1691).[2]:2[2]:171–172 The manuscript was partially translated into Urdu for Alexander Cunninhgam during his stay in Ladakh in 1847, who included a partial English version in his works, but the original manuscript and its Urdu translations no longer exist.[2]:2

- Ms.Sonam: This manuscript consists of approximately 40 pages and covers the entire history of the two Ladakhi dynasties until the Dogra conquest. The manuscript is a modernized and shortened version of Ms.C until events c. 1825, after which it contains extra details that are not covered by the other manuscripts. Its owner also added appendices and minor changes not originally contained in the manuscript, and it is known to be in the private possession of a 'Bri-guh-pa monk at the Lamayuru Monastery.[2]:2

Contents

The Ladakh Chronicles were split into several separate sections, with the Royal Genealogy of Ladakh being the principal chronicle.[4] The chronicles refers to several dynasties of kings, mentioning that some were descended from the mythological Tibetan hero Gesar.[1]:17[2]:16

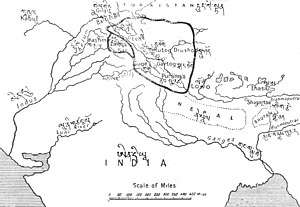

Tibetans controlled the area since 663 and was controlled by the Tibetan Empire until 842, after which the area was described by the chronicles as splintering into several principalities plagued by warfare and raiding.[1]:17[2]:13 The chronicles then describe the establishment of Maryul by descendants of the central Tibetan monarchy in the 10th century.[1]:17[2]:17–18 The chronicles describe the period of conflicts with the Mughal Empire during the late 14th to 16th centuries in Ladakh and Baltistan.[1]:18[2]:23, 26–28, 30 The chronicles then describe the development of the Namgyal dynasty and its expansion to Purig in the west and the Tibetan lands of Guge in the east.[1]:18[2]:28 The latter parts of the Ladakh Chronicles in manuscripts Ms. C and Ms. Sonam contain details about the surprise Dogra invasion of Ladakh.[2]:138–170

The chronicles also cover the first-millennium presence of Buddhism, the growth of Buddhism in the first half of the second millennium, and the introduction of Islam in the 16th century.[1]:17–18[2]:18–19, 30[6]:121–122

Treaty of Tingmosgang (1684)

The Ladakh Chronicles mention that the Ganden Phodrang Prime Minister Desi Sangye Gyatso of Tibet[7]:342:351 and the King Delek Namgyal of Ladakh[7]:351–353[2]:171–172 agreed on the Treaty of Tingmosgang (sometimes called the Treaty of Temisgam)[6] in the fortress of Tingmosgang at the conclusion of the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War in 1684. The original text of the Treaty of Tingmosgang no longer survives, but its contents are summarized in the Ladakh Chronicles.[8]:37:38:40

The summary contained in the Ladakh Chronicles includes six main clauses of the treaty:[7]:356[5]:115–118

- A general declaration of principle that the region of Guge (mNa'-ris-sKorgSum) was divided into three separate kingdoms in the 10th century;

- The Tibetan recognition of the independence of Ladakh and the restriction for the King of Ladakh from inviting foreign armies into Ladakh;

- The regulation of trade, subdivided into two subclauses, for Guge and the northern plain of Tibet (Byaṅ-thaṅ);

- A clause fixing the Ladakh-Tibet border at the Lha-ri stream at Demchok, but granting the King of Ladakh an enclave at Men-ser;

- Another clause regulating Ladakh-Tibet trade;

- The arrangement of a fee to Mi-'pham dBaṅ-po (then-regent of Ladakh) for his cost in arranging the treaty.

The trade regulations provided for Ladakh's exclusive right to trade in pashmina wool produced in Tibet, in exchange for brick-tea from Ladakh. Ladakh was also bound to send periodic missions to Lhasa carrying presents for the Dalai Lama.[9] The fee in the sixth clause was later paid by Desi Sangye Gyatso to Mi-'pham dBaii-po in the form of three estates in Tibet sometime between the autumn of 1684 and 1685.[7]:356

Historiographical issues

The origin, intent, and time of the authorship of the Ladakh Chronicles is unknown to modern historians.[10]:113 The chronicles have also been criticized for containing gaps and inconsistencies,[3]:7 as well as for lacking geographical details.[8]:40 Its existing translations, particularly concerning the Treaty of Tingmosgang, have also been called "patchwork".[7]:356[11]:99

Notes

- also called the Royal Chronicle of Ladakh

References

- Pirie, Fernanda (2007). Peace and Conflict in Ladakh: The Construction of a Fragile Web of Order. Brill's Tibetan studies library. 13. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004155961.

- Petech, Luciano (1977). The Kingdom of Ladakh: C. 950-1842 A.D. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

- Bray, John (2005). "Introduction: Locating Ladakhi History". In Bray, John (ed.). Ladakhi Histories: Local and Regional Perspectives. Brill's Tibetan Studies Library. 9. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004145511.

- "Ladakh chronicles". Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society. 28 (1): 87–91. 1941. doi:10.1080/03068374108730998. ISSN 0035-8789.

- Francke, August Hermann (1926). Thomas, F. W. (ed.). Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part (Volume) II.

- Howard, Neil (2005). "The Development of the Boundary between the State of Jammu & Kashmir and British India, and its Representation on Maps of the Lingti Plain". In Bray, John (ed.). Ladakhi Histories: Local and Regional Perspectives. Brill's Tibetan Studies Library. 9. Brill Publishers. p. 218. ISBN 9789004145511.

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (1968). "New light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal war of 1679—1684". East and West. 18 (3/4): 340–361. JSTOR 29755343.

- Lamb, Alastair (1965), "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF), The Australian Year Book of International Law: 37–52

- Warikoo, K. (2009), "India's gateway to Central Asia: trans-Himalayan trade and cultural movements through Kashmir and Ladakh, 1846–1947", in Warikoo, K. (ed.), Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives, Routledge, p. 4, ISBN 978-1-134-03294-5

- Jinpa, Nawang (2015). "Why Did Tibet and Ladakh Clash in the 17th Century?: Rethinking the Background to the 'Mongol War' in Ngari (1679-1684)". The Tibet Journal. 40 (2): 113–150. JSTOR tibetjournal.40.2.113.

- Emmer, Gerhard (2007). "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84". Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia. BRILL. pp. 81–108. ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9.