Charding Nullah

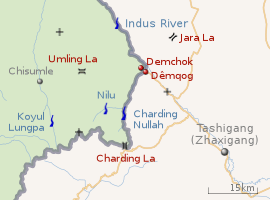

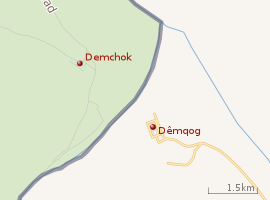

The Charding Nullah, traditionally known as the Lhari stream and called the Demchok River by China,[lower-alpha 1] is a small river that originates near the Charding La pass that is also on the border between the two countries and flows northeast to join the Indus River near a peak called "Lhari Karpo" (white holy peak). There are villages on both sides of the mouth of the river, romanised as Demchok and Dêmqog. The river serves as the de facto border between China and India in the Demchok sector.[lower-alpha 1]

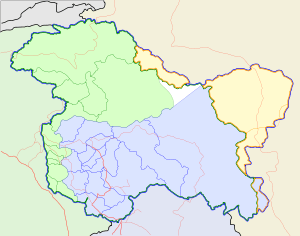

| Charding Nullah Lhari stream | |

|---|---|

Charding Nullah relative to the Kashmir region | |

Charding Nullah relative to the Tibet Autonomous Region | |

| Nickname(s) | Demchok River |

| Location | |

| country | India, China |

| province | Ladakh, Tibet Autonomous Region |

| district | Leh, Ngari Prefecture |

| subdistrict | Nyoma, Gar |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Charding La |

| • coordinates | 32.5573°N 79.3838°E |

| • elevation | 5,170 m (16,960 ft) |

| Mouth | Indus River |

• location | Demchok, Ladakh and Dêmqog, Ngari Prefecture |

• coordinates | 32°42′N 79°28′E |

• elevation | 4,200 m (13,800 ft)[1][2] |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Indus River |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Nilu Nullah |

| Demchok River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 典角河 | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Diǎnjiǎo hé | ||||||

| |||||||

Etymology

The Indian government refers to the river as "Charding Nullah" after its place of origin, the Charding La pass, with nullah meaning a mountain stream.

The Chinese government uses the term "Demchok river" by the location of its mouth, near the Demchok village.[lower-alpha 1]

The historical documents name the river as "Lhari stream".[4] Lhari,[lower-alpha 2] meaning "holy mountain" in Tibetan, is the name used for the white rocky peak (4,865 m) behind the village of Demchok.[5][6] It has also been referred to as "Lari Karpo" ("white lhari") and "Demchok Lari Karpo" in Tibetan documents.[7][lower-alpha 3] "Lhari stream at Demchok" is the phrase used in the 1684 Treaty of Tingmosgang,[10] forming the basis for the Indian government's identification of the stream with Charding Nullah.[11][lower-alpha 4]

Description

|

Source

The Charding Nullah originates below the Charding La pass, which is on a large spur that divides the Sutlej river basin from the Indus river basin. In this area, the Sutlej river tributaries flow southeast into West Tibet and the Indus river and its tributaries flow northwest, parallel to the Himalayan ranges.

Charding–Nilu Nullah Junction

The Charding Nullah flows northeast along a narrow mountain valley. Halfway down the valley it is joined by another nullah from the left, called Nilu Nullah (or Nilung/Ninglung). The Charding–Nilu Nullah Junction (CNNJ, 4900 m) is recognised by both the Indian and Chinese border troops as a strategic point.[13]

Changthang plateau

The entire area surrounding the Charding Nullah is referred to as the Changthang plateau. It consists of rocky mountain heights of Ladakh and Kailas ranges and sandy river valleys which are only good for grazing yaks, sheep and goats (the famous pashmina goats) reared by Changpa nomads.[14] The Indian-controlled northern side of the nullah is close to Hanle, the site of the Hanle Monastery. The Chinese-controlled southern side has the village of Tashigang (Zhaxigang) which also has a monastery, both having been built by the Ladakhi ruler Sengge Namgyal (r. 1616–1642).[15] At the end of Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War, the Tibetan troops retreated to Tashigang where they fortified themselves.[16]

|

Mouth

At the bottom of the valley, the Charding Nullah branches into a 2 km-wide delta as it joins the Indus river.[17] During the British colonial period, there were villages on both the sides of the delta, going by the name "Demchok". The southern village appears to have been the main one, frequently referred to by travelers.[18][19] Prior to the Sino-Indian War of 1962, India had established a border post to the south of the delta (the "New Demchok post"). As the war progressed, the post was evacuated and the Chinese forces occupied it.[20][6] The Chinese spelt the name of the village as Dêmqog. Travel writer Romesh Bhattacharji states they expected to set up a trading village, but India never renewed trade after the war. He states that the southern Dêmqog village has only commercial buildings whereas the northern village has security-related buildings.[21]

Notes

- On 21 September 1965, the Indian Government wrote to the Chinese Government, complaining of Chinese troops who were said to have "moved forward in strength right up to the Charding Nullah and have assumed a threatening posture at the Indian civilian post on the western [northwestern] side of the Nullah on the Indian side of the 'line of actual control'." The Chinese Government responded on 24 September stating, "In fact, it was Indian troops who on September 18, intruded into the vicinity of the Demchok village on the Chinese side of the 'line of actual control' after crossing the Demchok River from Parigas (in Tibet, China)..."[3]

- Alternative spellings of Lahri include "Lahri", "Lari" or "Lairi"

- Scholars translate the Tibetan term lha-ri as "soul mountain". Many peaks in Tibet are named lhari including a "Demchok lhari" in the northern suburbs of Lhasa.[8][9] "Karpo", meaning "white", serves to distinguish the Ladakh's mountain peak from the others.

- Fisher et al. states that the Lhari stream flows "five miles southeast of Demchok".[12] This seems incorrect. Rather the Indian alignment of the border is five miles southeast of Demchok. It follows the watershed of the Lhari stream/Charding Nullah. See Indian Report, Part 1 (1962), Q21 (p. 38)

References

- Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Ch. 9.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), pp. 374–375.

- India. Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1966), Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged and Agreements Signed Between the Governments of India and China: January 1965 - February 1966, White Paper No. XII (PDF), Ministry of External Affairs – via claudearpi.net

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 107.

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 160; Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Chapter 9: "Changthang: The High Plateau"

- Claude Arpi, The Case of Demchok, Indian Defence Review, 19 May 2017.

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 106–107.

- McKay, Alex (2015), Kailas Histories: Renunciate Traditions and the Construction of Himalayan Sacred Geography, BRILL, p. 520, ISBN 978-90-04-30618-9

- Khardo Hermitage (Khardo Ritrö), Mandala web site, University of Virginia, retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 38.

- Indian Report, Part 2 (1962), pp. 47–48: "There was only one Lhari in the area, and that was the stream joining the Indus near Demchok at Longitude 79° 28' E and Latitude 32° 42' N."

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 39.

- Chinese troops cross LAC in Ladakh again, India Today, 16 July 2014.

- Ahmed, Monisha (2004), "The Politics of Pashmina: The Changpas of Eastern Ladakh", Nomadic Peoples, New Series, White Horse Press, 8 (2): 89–106, doi:10.3167/082279404780446041, JSTOR 43123726

-

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 143: "Magnificent monasteries were built at Hemis, Theg-mchog (Chemrey), Anle [Hanle] and Tashigong [Tashigang]."

- Jina, Prem Singh (1996), Ladakh: The Land and the People, Indus Publishing, p. 88, ISBN 978-81-7387-057-6: "He [Sengge Namgyal] built many monasteries such as Hemis, Chemde, Wanla [Hanle] and Tashigang. He also built the castle of Leh palace."

- Shakspo, Nawang Tsering (1999), "The Foremost Teachers of the Kings of Ladakh", in Martijn van Beek; Kristoffer Brix Bertelsen; Poul Pedersen (eds.), Recent Research on Ladakh 8, Aarhus University Press, p. 286, ISBN 978-87-7288-791-3: "They founded the renowned Hemis Gonpa, Chemre Gonpa and Wanla Gonpa [Hanle]. Sengge Namgyal also had a monastery built at Tashigang in western Tibet."

-

- Emmer, the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (2007), p. 98

- Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001), p. 156

- Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area (2017): According to Hedin, "Right in front of us the monastery Tashi-gang gradually grows larger. Its walls are erected on the top of an isolated rock of solid porphyrite, which crops up from the bottom of the Indus valley like an island drawn out from north to south. (…) on the short side stand two round free-standing towers, (…). The whole is surrounded by a moat 10 feet deep (…)".

- Claude Arpi, Demchok and the New Silk Road: China's double standard, Indian Defence Review, 4 April 2015. "View of the nalla" image.

- Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area (2017), p. 353: 'At present officially located in India, the village of Demchok marked the border between Tibet and Ladakh for a long time. Abdul Wahid Radhu, a former representative of the Lopchak caravan, described Demchok in his travel account as "the first location on the Tibetan side of the border".'

- Indian Report, Part 3 (1962), pp. 3–4: According to a report by the governor of Ladakh in 1904–05, "I visited Demchok on the boundary with Lhasa. ... A nullah falls into the Indus river from the south-west and it (Demchok) is situated at the junction of the river. Across is the boundary of Lhasa, where there are 8 to 9 huts of the Lhasa zamindars. On this side there are only two zamindars."

- Cheema, Crimson Chinar (2015), p. 190.

- Bhattacharji, Ladakh (2012), Chapter 9: "Changthang: The High Plateau".

Bibliography

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890

- India, Ministry of External Affairs (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (September–December 1968), "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", East and West, Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO), 18 (3/4): 340–361, JSTOR 29755343

- Bhattacharji, Romesh (2012), Ladakh: Changing, Yet Unchanged, New Delhi: Rupa Publications – via Academia.edu

- Bray, John (Winter 1990), "The Lapchak Mission From Ladakh to Lhasa in British Indian Foreign Policy", The Tibet Journal, 15 (4): 75–96, JSTOR 43300375

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, pp. 51–, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854), Ladak: Physical, Statistical, Historical, London: Wm. H. Allen and Co – via archive.org

- Emmer, Gerhard (2007), "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, BRILL, pp. 81–108, ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via Questia

- Handa, O. C. (2001), Buddhist Western Himalaya: A Politico-Religious History, Indus Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-7387-124-5

- Howard, Neil; Howard, Kath (2014), "Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley, Eastern Ladakh, and a Consideration of Their Relationship to the History of Ladakh and Maryul", in Lo Bue, Erberto; Bray, John (eds.), Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, pp. 68–99, ISBN 9789004271807

- Lamb, Alastair (1964), The China-India border, Oxford University Press

- Lamb, Alastair (1965), "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF), The Australian Year Book of International Law: 37–52

- Lamb, Alastair (1989), Tibet, China & India, 1914-1950: a history of imperial diplomacy, Roxford Books

- Lange, Diana (2017), "Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area between Western Tibet, Ladakh, and Spiti", Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines,The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1

- Petech, Luciano (1977), The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D. (PDF), Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente – via academia.edu

- Rao, Gondker Narayana (1968), The India-China Border: A Reappraisal, Asia Publishing House

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969), Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger – via archive.org

External links

- Demchok Eastern Sector on OpenStreetMap (Chinese-controlled)

- Demchok Western Sector on OpenStreetMap (Indian-controlled)