Lackawanna Cut-Off

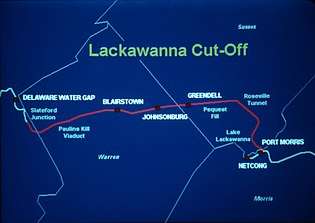

The Lackawanna Cut-Off (also known as the New Jersey Cut-Off or Hopatcong-Slateford Cut-Off) was built by the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W) between 1908 and 1911 and it ran from Port Morris Junction in Port Morris, New Jersey, to Slateford Junction in Slateford, Pennsylvania.

| Lackawanna Cut-Off | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Westbound Lackawanna Limited near Pequest Fill circa 1912. This photo later inspired a Phoebe Snow poster. | |||

| Overview | |||

| Status | Restoration in progress (Port Morris Junction–Andover) Abandoned (Andover–Slateford Junction) | ||

| Locale | New Jersey Pennsylvania | ||

| Termini | Port Morris Junction in Port Morris, New Jersey Slateford Junction in Slateford, Pennsylvania | ||

| Operation | |||

| Opened | 1911–1979, 2011–present (NJ Transit currently uses short section from Port Morris Jct. for temporary storage) | ||

| Closed | 1979–2011 (tracks removed in 1984) | ||

| Owner | State of New Jersey, Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Pennsylvania Northeast Regional Rail Authority[1] | ||

| Operator(s) | Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (1911–60) Erie Lackawanna Railroad (1960–76) Conrail (1976–79) NJ Transit (2011–present) | ||

| Character | Surface | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 28.45 mi (45.8 km) | ||

| Number of tracks | 2 (1911–58) 1 (1958–84) 0 (1984–2011) 1 under construction (2011–) passing sidings: 7 (1911); 3 (1979); 0 (1984) | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | ||

| Operating speed | 80 mph (130 km/h) | ||

| |||

When it opened on December 24, 1911, the Cut-Off was considered a "super-railroad", a state-of-the-art rail line, built upon large cuts and fills, and which included two large concrete viaducts that allowed for what was considered high-speed travel at that time. The line was part of a 400-mile (640 km) main line between Hoboken, New Jersey, and Buffalo, New York. The Cut-Off ran west for 28.5 miles (45.9 km) from Port Morris Junction — near the south end of Lake Hopatcong in New Jersey, about 45 miles (72 km) west-northwest of New York City — to Slateford Junction near the Delaware Water Gap in Pennsylvania.

The Cut-Off was 11 miles (18 km) shorter than the Lackawanna Old Road, the rail line it superseded; it had a much gentler ruling gradient (0.55% vs. 1.1%); and it had 42 fewer curves, with all but one permitting passenger train speeds of 70 mph (110 km/h) or more.[2] The Cut-Off also had no railroad crossings at the time of its construction. All but one of the line's 73 structures were built of reinforced concrete, a pioneering use of the material.[3] The construction of the roadbed required the movement of millions of tons of fill material using techniques similar to those used on the Panama Canal.[4]

Operated through a subsidiary, Lackawanna Railroad of New Jersey, the Cut-Off remained in continual operation for 68 years, through the Lackawanna's 1960 merger with the Erie Railroad to form the Erie Lackawanna Railroad, and the EL's conveyance into Conrail in 1976. Conrail ceased operation of the Cut-Off in January 1979 and filed for abandonment of the line in 1983, citing its excess east-west routes. It removed the track in 1984, then sold the right-of-way to private developers. Restoration to Andover, New Jersey, is ongoing but current projections indicate that it will take at least until 2021 to be completed.[5] In March 2020, the opening date of Andover station was pushed to 2025.[6]

Lackawanna Cut-Off | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Before the Cut-Off (1851–1905)

The line's origin involves two men who most likely never met: John I. Blair and William Truesdale. Blair built the DL&W's Warren Railroad, chartered in 1851 and completed in 1862, to provide a connection between the mainlines of the DL&W in Pennsylvania and the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) in New Jersey.[7] But when the Lackawanna-CNJ merger fell through and the Lackawanna merged with the Morris & Essex Railroad in New Jersey instead, the Warren Railroad became part of a circuitous patchwork of rail lines connecting two unanticipated merger partners.[4]

The 39-mile (63 km) route (later known as the "Old Road" after the New Jersey Cut-Off opened) had numerous curves that restricted trains to 50 mph (80 km/h). The bigger operational problem, however, was caused by the two tunnels on the line: Manunka Chunk Tunnel, a 975-foot (297 m) twin-bore tunnel whose eastern approach occasionally flooded with heavy rains; and the 2,969-foot (905 m) single-bore Oxford Tunnel, which was double-tracked in 1869 and reduced to gauntlet track in 1901. As more and more traffic moved over the line, Oxford Tunnel became the Lackawanna Railroad's worst bottleneck.[4][8]

Truesdale became DL&W president on March 2, 1899[9] with a mandate to upgrade the entire 900-mile (1,450 km) railroad.[10] Early on, the railroad focused on increasing freight capacity by using larger locomotives and cars, as well as strengthening bridges to handle these larger loads. Although Truesdale recognized early on that the Old Road needed to be replaced, it really wasn't until after 1905 that the railroad was in a position to take up the project in earnest. This led Truesdale to authorize teams of surveyors to map out potential replacement routes westward from Port Morris, New Jersey, to the Delaware River for what would be the railroad's largest project up until that time.

Planning and construction (1905–11)

During 1905–6, 14 routes were surveyed (labeled with letters of the alphabet), including several that would have required long tunnels. On September 1, 1906, a route without tunnels was chosen. This New Road (Route "M") would run from the crest of the watershed at Lake Hopatcong at Port Morris Junction to 2 mi (3.2 km) south of the Delaware Water Gap on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River at Slateford Junction.

At 28.5 miles (45.9 km), the line would be about 11 mi (18 km) shorter than the 39.6-mile (63.7 km) Old Road. The new route would have only 15 curves—42 fewer curves than the Old Road, the equivalent of more than four complete circles of curvature—which increased speeds and decreased running time—especially for freight, but for passenger trains as well. The ruling grade was cut in half from 1.1% to 0.55%.[2] The new line would also be built without railroad crossings to avoid collisions with automobiles and horse-drawn vehicles.[2]

Uncertain national economic conditions in 1907 delayed the official start of construction until August 1, 1908. The project was divided into seven sections, one for each contracting company. Sections 3–6 were 5 miles (8 km) each; Sections 1–2 and 7 were of varying lengths. (Theoretically, to divide the 28.5-mile (46 km) line evenly, the seven sections should have been just over four miles each, but that would have placed the Pequest Fill entirely within Section 3 and the two viaducts within Section 7.) The amount of work per mile varied; the largest share apparently went to David W. Flickwir, whose Section 3 included Roseville Tunnel and the eastern half of the Pequest Fill. DL&W chief engineer George G. Ray oversaw the project, although given the size and remote location of the project, Assistant Chief Engineer F.L. Wheaton was assigned the task of overseeing the construction in person.

To accommodate the labor gangs, deserted farmhouses were converted to barracks, with tent camps providing additional shelter. These workers, many of whom came from Italy and other foreign countries or other parts of the U.S., were recruited and would move on to other projects after their work on the Cut-Off was completed. These workers were viewed with suspicion by the local populace in Warren and Sussex counties, with the town of Blairstown going so far as to hire a watchman at $40 per month for the duration of the project. Supervisory personnel and skilled laborers stayed in local hotels, boarding houses, or in local farm houses, usually at exorbitant rates ($1–2 per day) during the years of construction.

With several thousand men working on the project for over three years, the area all along the Cut-Off, and as far west as Portland, Pennsylvania, benefitted financially.[4]

As many as 30 workers may have lost their lives building the Cut-Off. Most of their names remain unknown because they were registered with their contractor by number only. In 1910, for example, five workers were killed in a single blasting mishap near Port Morris, one of several deadly accidents that involved dynamite. Other workers died in machinery or cable car accidents, or landslides. At least one worker is known to have died of typhoid fever.

Sections

| Features | Length (ft) | Max. height or depth (ft) | Avg. height or depth (ft) | Concrete used (yds3) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1: Timothy Burke, miles 45.7–48.2 (Port Morris Jct. – cut west of CR 605 bridge) | |||||

| Port Morris Junction Tower | – | – | – | – | Reinforced concrete, closed in 1979. |

| McMickle Cut | 5,500 | 54 | 29 | 600,000 | Located west of Musconetcong River |

| Section 2: Waltz & Reece Construction Co., miles 48.2–50.2 (Cut west of CR 605 bridge – Lake Lackawanna) | |||||

| Waltz & Reece Cut | 3,600 | 114 | 37 | 822,400 | Crossed by Sussex County Route 605 overhead bridge |

| Bradbury Fill | 4,000 | 78 | 24 | 457,000 | Located in front of large cliff |

| Lubber Run Fill | 2,100 | 98 | 64 | 720,000 | At Lake Lackawanna |

| Section 3: David W. Flickwir, miles 50.2–55.8 (Lake Lackawanna – center of Pequest Fill) | |||||

| Wharton Fill | about 2,600 | – | – | – | Just east of Roseville Tunnel |

| Roseville Tunnel | 1,040 | – | – | 35,000 | Unstable rock made tunneling necessary instead of cut; track moved to center of bore in 1974. |

| Colby Cut | 2,800 | 110 | 45 | 462,342 | Rockslide detectors installed in 1950. |

| Pequest Fill (eastern half) | 16,500 | 110 | 75 | 6,625,648 | Numbers are totals; Pequest Fill was divided equally between two contractors |

| Section 4: Walter H. Gahagan, miles 55.8–60.8 (Center of Pequest Fill – Johnsonburg Station) | |||||

| Pequest Fill (western half) | – | – | – | – | World's largest railroad fill when built. |

| Greendell Station / tower | – | – | – | – | Reinforced concrete, closed ca. 1942–3; tower closed in 1938; a flag stop for many years |

| Section 5: Hyde, McFarlan & Burke, miles 60.8–65.8 (Johnsonburg Station – 1 mile west of Blairstown Station) | |||||

| Johnsonburg Station / creamery | – | – | – | – | Reinforced concrete, located on Ramsey Fill; closed in 1942–3; station razed in 2007. |

| Ramsey Fill | 2,800 | 80 | 21 | 805,481 | Location of Johnsonburg station |

| Armstrong Cut | 4,700 | 104 | 52 | 852,000 | Largest cut on line; north side of cut collapsed and trimmed back in 1941 |

| Blairstown Station / freight house | – | – | – | – | Reinforced concrete, located within Jones Cut; closed in Jan 1970 |

| Jones Cut | – | – | – | 578,000 | Location of Blairstown station |

| Vail Fill | 1,700 | 102 | 33 | 293,500 | Located on 1 degree curve |

| Section 6: Reiter, Curtis & Hill, miles 65.8–70.8 (1 mile west of Blairstown Station – west end of Paulinskill Viaduct) | |||||

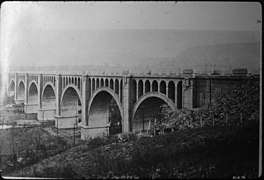

| Paulins Kill Viaduct | 1,100 | 115 | – | 43,212 | Reinforced concrete bridge over Paulinskill and New York, Susquehanna & Western Railroad; world's largest reinforced concrete structure when built. |

| Section 7: Smith, McCormick Co., miles 70.8–74.3 (west end of Paulinskill Viaduct – Slateford Jct.) | |||||

| Delaware River Viaduct | 1,452 | 65 | – | – | Reinforced concrete; originally planned as a curved structure. Smith, McCormick Co. built the viaduct and sub-contracted the grading of Section 7 to James A. Hart Co. of New York.[11][12] |

| Slateford Junction Tower | – | – | – | – | Reinforced concrete, closed in Jan 1951 |

The Cut-Off's reinforced concrete structures (73 in all), which consumed 266,885 cubic yards (204,048 m3) of concrete and 735 tons of steel, include underpasses, culverts, and the two large viaducts on the western end of the line.[4]

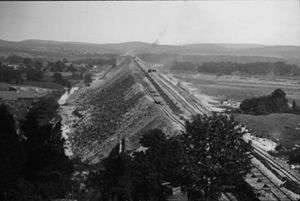

Some five million pounds (2,300 t) of dynamite were used to blast the cuts on the line. A total of 14,621,100 cubic yards (11,178,600 m3) of fill material was required for the project, more than could be obtained from the project's cuts. This forced the DL&W to purchase 760 acres (310 ha) of farmland for borrow pits.[2] Depending on the fill size, material was dumped from trains that backed out onto track on wooden trestles or suspended on cables between steel towers. During construction, several foreign governments sent representatives on inspection tours to study these new techniques.[4]

The Pequest Fill extended west of Andover to Huntsville, New Jersey. It was at its maximum height 110 feet (34 m) tall and was 3.12 miles (5.0 km) long, requiring 6,625,648 cubic yards (5,065,671 m3) of fill.[2] Armstrong Cut was 100 feet (30 m) deep and 1 mile (1.6 km) long, mostly through solid rock. The line's deepest cut was Colby Cut (immediately west of what would become Roseville Tunnel) at 130 feet (40 m) deep. The tunnel was not in the original plans for the Cut-Off, and in fact much of the cut above the tunnel had already been blasted when in October 1909 unstable anticline rock was encountered,[13] leading to a decision to abandon the cut and to blast what would become a 1,040-foot (320 m) tunnel instead.[14] Contractor David W. Flickwir, whose section included Roseville Tunnel and the eastern half of the Pequest Fill, worked around the clock during the summer of 1911 when construction fell behind schedule.[4]

Stations were built in Greendell, Johnsonburg and Blairstown; the Greendell area was already being served by the nearby Lehigh & Hudson River Railroad in Tranquility.[4] Interlocking towers were built at Port Morris Junction and Greendell, New Jersey, and Slateford Junction in Pennsylvania.

The final cost of the project was $11,065,512 in 1911 US dollars, equal to $303,629,745 today.[14] Although exact modern comparisons of cost are difficult, it is estimated that the same project today might cost upwards of $1 billion US dollars.[15]

Heyday (1911–58)

The first revenue train to operate on the Cut-Off under the new timetable that went into effect at 12:01 a.m. on December 24, 1911, was No. 15, a westbound passenger train that passed through Port Morris Junction at about 3:36 a.m.[16] Most long-distance trains that traversed the Old Road shifted to the Cut-Off, effectively downgrading the older line to secondary status.[4]

The Cut-Off was built to permit unrestricted speeds for passenger trains of 70 mph (110 km/h) (heavier rail that was installed later allowed speeds to increase to 80 mph (130 km/h)). Sidings were built at Slateford, Hainesburg, Johnsonburg, Greendell, Roseville, and Port Morris; about 25% of the route contained additional sidings. With upwards of 50 trains a day,[17] towermen often ordered freight trains to take a siding or even be rerouted over the Old Road. As traffic decreased, Hainesburg, Johnsonburg and Roseville sidings were altered or removed. The remaining sidings remained in use until 1979.[18]

Roseville Tunnel posed occasional problems, especially during the winter with snow and ice buildup. Rockslides were a constant threat west of the tunnel. In recognition of this, a detector fence was installed west of Roseville Tunnel in 1950 to change trackside signals to red if rocks fell.[19] The most serious rockslide to ever occur on the line, however, would take place within Armstrong Cut (just west of Johnsonburg) in 1941, closing the line for nearly a month, and causing trains to be rerouted via the Old Road.[20] The north side of Armstrong Cut was trimmed back to prevent further rockslides.[20]

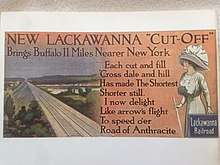

Passenger

The Cut-Off was a scenic highlight for passenger trains. Early in the 20th century, the DL&W's woman in white—Phoebe Snow— was featured in a poster that touted the new line and the Pequest Fill. At that time, and into the early diesel era (late 1940s), the Lackawanna Limited was the railroad's premier train. It was later joined by the Pocono Express, the Owl, and the Twilight. While the Lackawanna only operated mainline passenger trains between Hoboken, New Jersey, and Buffalo, New York, passengers could transfer to and from other railroads at Buffalo. For example, the Nickel Plate offered through sleeper service to St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri, via the Lackawanna.

In 1949, the Lackawanna began modernizing its mainline passenger coaches. The railroad had already begun replacing steam engines with diesels in 1946, starting with mainline passenger trains. The Lackawanna Limited was also modernized and renamed the Phoebe Snow, helping breathe freshness back into a passenger train program that had seen only modest improvements since the 1930s.[21] The Phoebe Snow would run for 11 years as a DL&W train and then as an Erie Lackawanna train from 1963 until November 1966. The Lake Cities, ironically a former Erie Railroad train, became the last regularly-scheduled passenger train on the Cut-Off, making its last run on January 6, 1970.

The only station on the Cut-Off at which mainline passenger trains would stop was Blairstown. Blairstown was also the first stop on westbound trains where passengers were permitted to disembark (i.e. westbound passengers boarding and detraining east of Blairstown were required to use suburban train service instead). This explains why Blairstown was the first stop listed on the destination board at the boarding gate at Hoboken for trains travelling via Scranton. In later years, Blairstown had a somewhat unusual facet of operation: any trains arriving after the station agent went home for the night would automatically activate the station platform lights as the train entered the signal block. This practice was abandoned after passenger service ended.

Freight

Besides cutting travel time, the Cut-Off required fewer engines to pull eastbound freights up to the summit at Port Morris. For westbound freights, the challenge was keeping trains from going too fast. Initially, no speed limit existed on the Cut-Off, with engineers (both freight and passenger) being expected to exercise "good judgment". By the 1920s, however, most freights were restricted to 50 mph (80 km/h) or less, depending on the priority of the train and the type of locomotive and rail cars. By 1943, 131-pound-per-yard (65 kg/m) rail had been installed on the Cut-Off,[22] which permitted fast freights to run at 60 mph (97 km/h) through the Erie Lackawanna years. After Conrail took over operations in 1976, the speed limit was decreased to 50 mph.[23]

Local freights served customers at all three stations on the Cut-Off. Over the years, Blairstown handled the most local freight. The Johnsonburg creamery, built in anticipation of the opening of the line, served local dairy farmers for years. Another creamery, an ice house, and a stock yard were built at Greendell.[24] The final local shipment was shipped in 1978 by Conrail: cattle feed for a customer in Johnsonburg that was delivered to Greendell, as the siding at Johnsonburg no longer existed.

Accidents

The Cut-Off has seen two accidents during its operation:

- On September 17, 1929, at 6:31 a.m., an eastbound extra freight consisting of 47 cars and a caboose was rammed from behind by a deadhead freight of 24 empty express refrigerator cars and a coach. The engineer at fault was reportedly eating his lunch as his train passed a "restricted speed" signal. He also missed two track torpedoes that exploded as his engine ran over them, and then missed the red signal near the west portal of Roseville Tunnel. His train emerged from the tunnel at 30 mph (48 km/h) and rear-ended a freight train traveling about 11 mph (18 km/h). The impact derailed the trailing locomotive and its coal tender, the caboose of the leading freight, and two express cars in the trailing freight. The two cars immediately in front of the caboose were also damaged. Four employees were injured.[17]

- In 1960, a freight train carrying automobiles derailed at Greendell.

Three other accidents, which did not occur on the Cut-Off itself, did indirectly involve the line:

- On June 16, 1925, an eastbound passenger special from Chicago scheduled to run over the Cut-Off was rerouted over the Old Road to avoid freight traffic. A storm had washed debris onto the Hazen Road grade crossing three miles (4.8 km) west of Hackettstown, New Jersey, and at 2:24 a.m., the engine and train derailed. Forty-seven people died, most of them scalded by steam escaping the wrecked locomotive.[25] See:

- On May 15, 1948 at 11:27 p.m., a westbound passenger train, No. 9, derailed at the 40 mph (64 km/h) curve at Point of Gap while going faster than 73 mph (117 km/h). It was a misty night and the train had left Hoboken 38 minutes late, and had made up 14 minutes on the schedule by the time it was recorded as having passed Slateford Tower, suggesting that the train may have exceeded the speed limit during the 75-mile (121 km) trip.[22] The engine (No. 1136, a 4-6-2) and tender overturned and ended upright in the Delaware River. The first car uncoupled from the tender and ended up in the river behind it. The remaining seven cars of the train continued for another 1,735 feet (529 m) down the track. The engineer and firemen were killed.

- On August 10, 1958, shortly after 6:00 am, a string of 14 cars—cement cars, boxcars, and a caboose—broke loose from Port Morris, beginning one of the longest runaways in North American railroading history. The crew of the East End Drill was awaiting orders to move the cars when they began to drift westbound down the grade. Engineless, the cars ran through a switch and onto the eastbound track of the Cut-Off, beginning a 29-mile (47 km) journey that reached a top speed that was estimated to be nearly 80 mph (130 km/h).[26] A chase locomotive was dispatched from Port Morris in a futile attempt to try to catch the cars. Within a half-hour ten of the cars in the string had derailed at the sharp (40 mph or 64 km/h) curve at Point of Gap in the Delaware Water Gap, falling into the Delaware River at approximately the same location as the 1948 accident. The lead caboose and three cars did not derail, however, and travelled another 4-mile (6.4 km) before stopping. No one was injured, although an eastbound freight (NE-4) quickly took Greendell siding just ahead of the runaway cars, narrowly avoiding a catastrophic collision. The runaway was blamed on a worker who had not properly set the brakes.[27]

Decline (1958–79)

The DL&W was one of the most profitable corporations in the U.S. when it built the Cut-Off.[4][28] That profitability declined sharply after World War II, leading to the 1960 merger with the Erie Railroad.[29] DL&W single-tracked the Cut-Off in 1958 in anticipation of the Erie merger. The westbound track was removed, leaving a four-mile (6.4 km) passing siding at Greendell and shorter sidings at Port Morris and Slateford. After the merger, most freight traffic shifted to the Erie's mainline through Port Jervis, New York.[30][31] With the cessation of passenger service in 1970, the Cut-Off became relatively quiet for several years. In 1972, the CNJ abandoned operations in Pennsylvania, causing through freights to be run daily between Elizabeth, New Jersey, and Scranton, using the Cut-Off and the CNJ's High Bridge Branch. (This arrangement with the CNJ would end on April 1, 1976, with the creation of Conrail).[31] As such, when Penn Central closed its Maybrook, New York Yard in 1970, the original reason for using the "Erie side" suddenly no longer existed. As a result, the EL looked to upgrade the "Scranton side", and by 1974 nearly all EL freights had been re-routed to the Scranton Division via the Cut-Off.[31]

After Conrail took over, existing labor contracts kept EL's freight schedule largely unchanged. The railroad replaced many rotted ties, returning it to better physical condition. But Conrail eventually shifted all freight traffic to other routes, citing the grades over the Pocono Mountains and EL's early-1960s severing of the Boonton Branch near Paterson, New Jersey as reasons for moving rail traffic off of the route, leading Conrail to run its final through freights in late 1978 and officially ended service on the Cut-Off in January 1979. Routine maintenance on the line ceased, and the signal system was shut off. Scranton-Slateford freights continued running into 1980 when coal delivered to the Metropolitan Edison power plant in Portland, Pennsylvania, shifted from the Scranton Division to the former Bangor & Portland Railway.[18]

Preservation and service restoration (1979–present)

Efforts to preserve the Cut-Off began shortly after Conrail ended service on it in 1979. An Amtrak inspection train ran in November of that year, and counties in New Jersey and Pennsylvania made attempts to acquire the line. Nevertheless, Conrail removed the tracks on the Cut-Off in 1984, and in the following year sold the right-of-way to two different land developers. In 2001, the State of New Jersey acquired the right-of-way through eminent domain, and the short section in Pennsylvania was conveyed to the Monroe County Railroad Authority. Subsequent federal studies conducted on the Cut-Off and the mainline into Pennsylvania found a need for the restoration of passenger service.

In 2011, after a nearly three-decade effort to reactivate the line, NJ Transit launched the Lackawanna Cut-Off Restoration Project. The first phase aimed to link Port Morris Junction to Andover, New Jersey (Andover station), 7.3 miles (11.7 km) away. By December 2011, about 1 mile (1.6 km) of track had been installed from Port Morris Junction west to Stanhope, New Jersey. As of 2019, about 4.25 miles (6.84 km) of rail, in three unconnected sections, has been laid between Port Morris and Lake Lackawanna, and most of the right-of-way between Port Morris Junction and the lake had been cleared of trees and debris. All environmental issues have been resolved. Based on current projections, the earliest that commuter operations could begin would be 2021.[5]

Although no specific plans have yet to be announced about the restoration of service west of Andover, a federal study has examined the feasibility of an extension into northeastern Pennsylvania, possibly as far as Scranton; funding for an update to this study is currently under investigation.[1]

Gallery

From top left, photos depict scenes from east to west.

- 1985 aerial view of Port Morris Junction and railyard; Cut-Off branches off to the right in straight line; Montclair-Boonton Line to Hackettstown curves off to left.

- A NJ Transit train at Port Morris, New Jersey in 1991 passes the spot where the connecting switch to the Lackawanna Cut-Off would later be rebuilt (Port Morris Junction).

- Port Morris ("UN") Tower had not seen a regularly scheduled train pass in over a decade when this photo was taken in 1990. The connection to NJ Transit's Montclair-Boonton Line to New York is a short distance beyond the tower.

The Sussex County Route 605 bridge over the Cut-Off in Byram, NJ, shown here in 1989, was replaced by a much wider bridge that opened in 2008. The original bridge was retained and now carries a hiking trail.

The Sussex County Route 605 bridge over the Cut-Off in Byram, NJ, shown here in 1989, was replaced by a much wider bridge that opened in 2008. The original bridge was retained and now carries a hiking trail. Hoboken-bound railfan excursion just east of Roseville Tunnel, June 1973.

Hoboken-bound railfan excursion just east of Roseville Tunnel, June 1973.- Roseville Tunnel looking west about five years after the tracks were removed. The hill above the tunnel has been partially blasted away, part of the original aborted plan to create Roseville Cut.

- Andover, a proposed station site (on right); photo looks west onto the Pequest Fill.

The US Route 206 underpass that crosses under the Pequest Fill facing north towards Andover, NJ. Out of view to the left is the Sussex Branch, which parallels Route 206.

The US Route 206 underpass that crosses under the Pequest Fill facing north towards Andover, NJ. Out of view to the left is the Sussex Branch, which parallels Route 206.- The L&HR crossed under the Cut-Off near Tranquility, New Jersey. As part of a route consolidation plan, the Erie Lackawanna proposed in 1972 that a connecting line for freights be built from the L&HR here.

October 2010 View looking west on the Pequest Fill in Andover, New Jersey, where it crosses over US Route 206 and the Sussex Branch.

October 2010 View looking west on the Pequest Fill in Andover, New Jersey, where it crosses over US Route 206 and the Sussex Branch.- A view facing south from atop the Pequest Fill similar to what passengers travelling on the Cut-Off might have seen.

Construction of the Pequest Fill near Tranquility, New Jersey nears its completion during summer 1911.

Construction of the Pequest Fill near Tranquility, New Jersey nears its completion during summer 1911.- Greendell station (foreground) and interlocking tower (background) facing east in 1988. The tower closed in 1938. One track was removed (leaving two tracks at this location) when the Cut-Off was singled-tracked in 1958.[32] The station was rebuilt by Gerald Turco, but has since fallen into disrepair.

- Johnsonburg (station on right, creamery on left) was a flag stop for most of its existence. The station building acted as a construction command post for about a month following a massive landslide within Armstrong Cut (distant background) in 1941. The station closed about a year or two later, and was razed in 2007.

- The westbound Lackawanna Limited nears Paulina, New Jersey, circa 1912.

- Blairstown. Commuter tickets were sold here until 1970, after which the building housed a radio station, WHCY-FM, until the 1990s. A freight station was also here, behind the station in this view facing west. The station building is currently privately owned

Fill work west of Blairstown in March 1909. Note the tower in the distance (far left of photo). The twin 70-foot (21.5 m) tower in the foreground provides some idea of the scale of the fill to be constructed

Fill work west of Blairstown in March 1909. Note the tower in the distance (far left of photo). The twin 70-foot (21.5 m) tower in the foreground provides some idea of the scale of the fill to be constructed The Paulins Kill Viaduct in Hainesburg, New Jersey at about the time of the opening of the Cut-Off. Note that the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railroad (NYS&W) passes beneath the bridge, under the second arch from the right; Hainesburg Station on the NYS&W was located below and just east of the viaduct.

The Paulins Kill Viaduct in Hainesburg, New Jersey at about the time of the opening of the Cut-Off. Note that the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railroad (NYS&W) passes beneath the bridge, under the second arch from the right; Hainesburg Station on the NYS&W was located below and just east of the viaduct. The rural nature of the area through which the Cut-Off ran is evident in this 1912 photo (from a cracked glass plate negative) just west of the Paulinskill Viaduct. Note the short string of boxcars sitting on Hainesburg Siding. About 25 percent of the Cut-Off had rail sidings.[4]

The rural nature of the area through which the Cut-Off ran is evident in this 1912 photo (from a cracked glass plate negative) just west of the Paulinskill Viaduct. Note the short string of boxcars sitting on Hainesburg Siding. About 25 percent of the Cut-Off had rail sidings.[4] The tunnel for the L&NE railway (right) never saw a train, save for the dinky trains that built the tunnel. The tunnel for NJ Route 94 is on the left. The L&NE tunnel currently provides access to Knowlton Township's Tunnel Field.

The tunnel for the L&NE railway (right) never saw a train, save for the dinky trains that built the tunnel. The tunnel for NJ Route 94 is on the left. The L&NE tunnel currently provides access to Knowlton Township's Tunnel Field.- The Delaware River Viaduct looking north towards the Delaware Water Gap. Deteriorated bridge decking will need to be replaced before service is restored.

The Lackawanna's Old Road where it passes under the Delaware River Viaduct in Pennsylvania. The tracks have been shifted to the center of the underpass to give greater overhead clearance.

The Lackawanna's Old Road where it passes under the Delaware River Viaduct in Pennsylvania. The tracks have been shifted to the center of the underpass to give greater overhead clearance.- Slateford Junction, looking north to the Delaware Water Gap. The Cut-Off (left) and the Old Road (right) converge about 1,500 ft (460 m) past the obscured Slateford Tower.

Notes

- "New Jersey – Pennsylvania Lackawanna Cut-Off Passenger Rail Service Restoration Project Environmental Assessment" (PDF). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, and New Jersey Transit in cooperation with U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. June 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 36

- The only exception was the steel-on-concrete-abutments bridge over the Morris Canal near Port Morris; it was removed and the gap filled in after the canal was abandoned in 1924. The Hopatcong-Slateford Cut-Off, C.W. Simpson, Resident Engineer, Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad, Railway Age Gazette, Vol 54, No. 1, January 3, 1913.

- Lowenthal, Larry; William T. Greenberg Jr. (1987). The Lackawanna Railroad in Northwestern New Jersey. Tri-State Railway Historical Society, Inc. pp. 10–98, 101. ISBN 978-0-9607444-2-8.

- Scruton, Bruce A. (August 10, 2017). "New culvert OK'd to put Andover rail station on track". New Jersey Herald. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- Krawczeniuk, Borys (March 2, 2020). "New study drops cost of passenger train comeback". The Citizens' Voice. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- The six-foot-gauge Warren Railroad ran from the junction with the CNJ at Hampton, New Jersey, through Washington and Oxford, and connected with the DL&W at the Delaware River near Delaware, New Jersey, and Portland, Pennsylvania.

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 34

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 17

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 18

- September 1, 1906, Map of Delaware Valley Cut-Off, Commissioned by DL&W

- Dana, Richard Turner; Saunders, William Lawrence (1911). Rock Drilling with Particular Reference to Open Cut Excavation and Submarine Rock Removal. New York: J. Wiley & Sons.

- DL&W Presidents' correspondence file: October 28, 1909; Steamtown National Historic Site, Scranton, Pennsylvania.

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 39

- Lowenthal, Larry; William T. Greenberg Jr. (1987). The Lackawanna Railroad in Northwestern New Jersey. Tri-State Railway Historical Society, Inc. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-9607444-2-8.

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Employee Timetable dated December 24, 1911.

- Interstate Commerce Commission report, "Report of the Director of the Bureau of Safety in reinvestigation of an accident which occurred on the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Near Greendell, New Jersey, on September 17, 1929, dated January 10, 1930

- Dorflinger, Donald (1984–1985). "Farewell to the Lackawanna Cut-Off (Parts I-IV)". The Block Line. Morristown, New Jersey: Tri-State Railway Historical Society.

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad employee timetable, 1950.

- Taber & Taber 1981, p. 745

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 169

- Interstate Commerce Commission Investigation No. 3182. THE DELAWARE, LACKAWANNA AND WESTERN RAILROAD COMPANY, Accident near Slateford Jct., Pa., on May 15, 1948.

- Erie Lackawanna – Death of an American Railroad, 1938–1992, by H. Roger Grant, Stanford University Press, 1994.

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 41

- Dale, Frank (1995). Disaster at Rockport. Hackettstown Historical Society.

- http://lists.railfan.net/erielack-digest/200008/msg00157.html

- East Stoudsburg News-Record, page 1, August 11, 1948

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 53

- Taber & Taber 1980, pp. 134–139

- Taber & Taber 1980, p. 145

- Zimmermann, Karl R. (1983). Quadrant Press Review 3: Erie Lackawanna East. Quadrant Press Inc.

- Taber & Taber 1981, p. 739

References

- Taber, Thomas Townsend; Taber, Thomas Townsend III (1980). The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad in the Twentieth Century. 1. Muncy, PA: Privately printed. ISBN 0-9603398-2-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taber, Thomas Townsend; Taber, Thomas Townsend III (1981). The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad in the Twentieth Century. 2. Muncy, PA: Privately printed. ISBN 0-9603398-3-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Lackawanna Railroad in Northwestern New Jersey by Larry Lowenthal and William T. Greenberg, Jr., Tri-State Railway Historical Society, Inc., 1987.

- Farewell to the Lackawanna Cut-Off (Parts I-IV), by Don Dorflinger, published in the Block Line, Tri-State Railway Historical Society, Inc., 1984–1985.

- Grant, H. Roger (1994). Erie Lackawanna: The Death of an American Railroad, 1938-1992. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804723572. OCLC 246668407.

- The Lackawanna Story – The First Hundred Years of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad , by Robert J. Casey & W.A.S. Douglas, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1951.

- Erie Lackawanna East, by Karl R. Zimmermann, Quadrant Press, Inc., 1975.

- The Route of Phoebe Snow – A Story of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, by Shelden S. King, Wilprint, Inc., 1986.

- The Lackawanna Cut-Off Right-of-Way Use and Extension Study (for the Counties of Morris, Sussex and Warren), Gannett Fleming and Kaiser Engineers, Corp., September 1989.

- Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Company, Timetable No. 85, November 14, 1943

- Erie-Lackawanna Railroad Company, Timetable No. 4, October 28, 1962

- Map of Proposed Route of Lackawanna Railroad From Hopatcong to Slateford. L. Bush – Chief Engineer. September 1, 1906.

Further reading

- Barnickel, Don; Williams, Paula. "Touring the Lackawanna Cutoff". Skylands Visitor.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lackawanna Cut-Off. |