LaTeX

LaTeX (/ˈlɑːtɛx/ LAH-tekh or /ˈleɪtɛx/ LAY-tekh[1]), stylized within the system as LaTeX, is a software system for document preparation.[2] When writing, the writer uses plain text as opposed to the formatted text found in "What You See Is What You Get" word processors like Microsoft Word, LibreOffice Writer and Apple Pages. The writer uses markup tagging conventions to define the general structure of a document (such as article, book, and letter), to stylise text throughout a document (such as bold and italics), and to add citations and cross-references. A TeX distribution such as TeX Live or MikTeX is used to produce an output file (such as PDF or DVI) suitable for printing or digital distribution.

| |

| Original author(s) | Leslie Lamport |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 1984 |

| Repository | |

| Type | Typesetting |

| License | LaTeX Project Public License (LPPL) |

| Website | latex-project |

LaTeX is widely used in academia[3][4] for the communication and publication of scientific documents in many fields, including mathematics, statistics, computer science, engineering, physics, economics, linguistics, quantitative psychology, philosophy, and political science. It also has a prominent role in the preparation and publication of books and articles that contain complex multilingual materials, such as Sanskrit and Greek.[5] LaTeX uses the TeX typesetting program for formatting its output, and is itself written in the TeX macro language.

LaTeX can be used as a standalone document preparation system, or as an intermediate format. In the latter role, for example, it is sometimes used as part of a pipeline for translating DocBook and other XML-based formats to PDF. The typesetting system offers programmable desktop publishing features and extensive facilities for automating most aspects of typesetting and desktop publishing, including numbering and cross-referencing of tables and figures, chapter and section headings, the inclusion of graphics, page layout, indexing and bibliographies.[6]

Like TeX, LaTeX started as a writing tool for mathematicians and computer scientists, but even from early in its development, it has also been taken up by scholars who needed to write documents that include complex math expressions or non-Latin scripts, such as Arabic, Devanagari and Chinese.[7]

LaTeX is intended to provide a high-level, descriptive markup language that accesses the power of TeX in an easier way for writers. In essence, TeX handles the layout side, while LaTeX handles the content side for document processing. LaTeX comprises a collection of TeX macros and a program to process LaTeX documents, and because the plain TeX formatting commands are elementary, it provides authors with ready-made commands for formatting and layout requirements such as chapter headings, footnotes, cross-references and bibliographies.

LaTeX was originally written in the early 1980s by Leslie Lamport at SRI International.[8] The current version is LaTeX2e (stylised as LaTeX2ε). LaTeX is free software and is distributed under the LaTeX Project Public License (LPPL).[9]

Typesetting system

LaTeX attempts to follow the design philosophy of separating presentation from content, so that authors can focus on the content of what they are writing without attending simultaneously to its visual appearance. In preparing a LaTeX document, the author specifies the logical structure using simple, familiar concepts such as chapter, section, table, figure, etc., and lets the LaTeX system handle the formatting and layout of these structures. As a result, it encourages the separation of the layout from the content — while still allowing manual typesetting adjustments whenever needed. This concept is similar to the mechanism by which many word processors allow styles to be defined globally for an entire document, or the use of Cascading Style Sheets in styling HTML documents.

The LaTeX system is a markup language that handles typesetting and rendering[10], and can be arbitrarily extended by using the underlying macro language to develop custom macros such as new environments and commands. Such macros are often collected into packages, which could then be made available to address some specific typesetting needs such as the formatting of complex mathematical expressions or graphics[6] (e.g., the use of the align environment provided by the amsmath package to produce aligned equations).

In order to create a document in LaTeX, you first write a file, say document.tex, using your preferred text editor. Then you give your document.tex file as input to the TeX program (with the LaTeX macros loaded), which prompts TeX to write out a file suitable for onscreen viewing or printing.[11] This write-format-preview cycle is one of the chief ways in which working with LaTeX differs from the What-You-See-Is-What-You-Get (WYSIWYG) style of document editing. It is similar to the code-compile-execute cycle known to the computer programmers. Today, many LaTeX-aware editing programs make this cycle a simple matter through the pressing a single key, while showing the output preview on the screen beside the input window. Some online LaTeX editors even automatically refresh the preview,[12][13][14] while other online tools provide incremental editing in-place, mixed in with the preview in a streamlined single window.[15]

Example

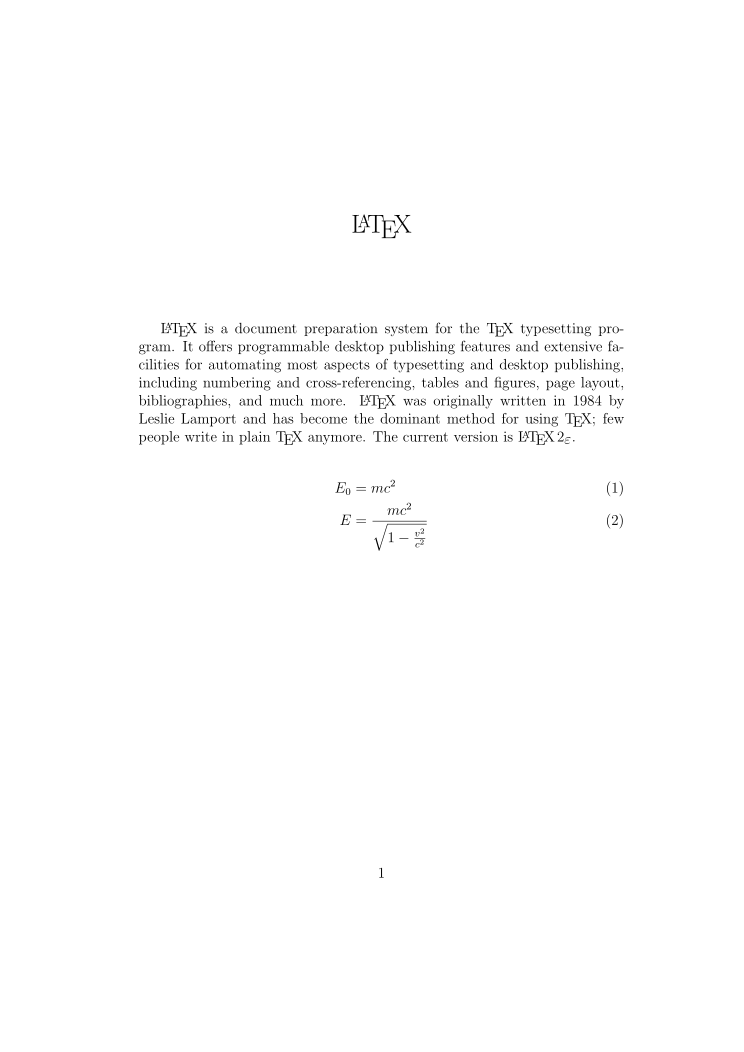

The example below shows the LaTeX input and corresponding output:

| Input | Output |

|---|---|

\documentclass{article} % Starts a article

\usepackage{amsmath} % Imports amsmath

\title{\LaTeX} % Title

\begin{document} % Begins a document

\maketitle

\LaTeX{} is a document preparation system for

the \TeX{} typesetting program. It offers

programmable desktop publishing features and

extensive facilities for automating most

aspects of typesetting and desktop publishing,

including numbering and cross-referencing,

tables and figures, page layout,

bibliographies, and much more. \LaTeX{} was

originally written in 1984 by Leslie Lamport

and has become the dominant method for using

\TeX; few people write in plain \TeX{} anymore.

The current version is \LaTeXe.

% This is a comment, not shown in final output.

% The following shows typesetting power of LaTeX:

\begin{align}

E_0 &= mc^2 \\

E &= \frac{mc^2}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}

\end{align}

\end{document}

|

|

Note how the equation for (highlighted in the example code) was typeset by the markup:

E &= \frac{mc^2}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}

where the square root is denoted by "\sqrt{argument}", and the fractions by "\frac{numerator}{denominator}".

Pronouncing and writing "LaTeX"

The characters T, E, X in the name come from the Greek capital letters tau, epsilon, and chi, as the name of TeX derives from the Ancient Greek: τέχνη (skill, art, technique); for this reason, TeX's creator Donald Knuth promotes a pronunciation of /tɛx/ (tekh)[16] (that is, with a voiceless velar fricative as in Modern Greek, similar to the ch in loch). Lamport remarks that "TeX is usually pronounced tech, making lah-teck, lah-teck, and lay-teck the logical choices; but language is not always logical, so lay-tecks is also possible."[17]

\LaTeX macroThe name is traditionally printed in running text with a special typographical logo: LaTeX.

In media where the logo cannot be precisely reproduced in running text, the word is typically given the unique capitalization LaTeX. Alternatively, the TeX, LaTeX[18] and XeTeX[19] logos can also be rendered via pure CSS and XHTML for use in graphical web browsers — by following the specifications of the internal \LaTeX macro.[20]

Licensing

LaTeX is typically distributed along with plain TeX under a free software license: the LaTeX Project Public License (LPPL).[21] The LPPL is not compatible with the GNU General Public License, as it requires that modified files must be clearly differentiable from their originals (usually by changing the filename); this was done to ensure that files that depend on other files will produce the expected behavior and avoid dependency hell. The LPPL is DFSG compliant as of version 1.3. As free software, LaTeX is available on most operating systems, which include UNIX (Solaris, HP-UX, AIX), BSD (FreeBSD, macOS, NetBSD, OpenBSD), Linux (Red Hat, Debian, Arch, Gentoo), Windows, DOS, RISC OS, AmigaOS and Plan9.

Related software

As a macro package, LaTeX provides a set of macros for TeX to interpret. There are many other macro packages for TeX, including Plain TeX, GNU Texinfo, AMSTeX, and ConTeXt.

When TeX "compiles" a document, it follows (from the user's point of view) the following processing sequence: Macros → TeX → Driver → Output. Different implementations of each of these steps are typically available in TeX distributions. Traditional TeX will output a DVI file, which is usually converted to a PostScript file. More recently, Hàn Thế Thành and others have written a new implementation of TeX called pdfTeX, which also outputs to PDF and takes advantage of features available in that format.[22] The XeTeX engine developed by Jonathan Kew, on the other hand, merges modern font technologies and Unicode with TeX.[23]

The default font for LaTeX is Knuth's Computer Modern, which gives default documents created with LaTeX the same distinctive look as those created with plain TeX. XeTeX allows the use of OpenType and TrueType (that is, outlined) fonts for output files.

There are also many editors for LaTeX, some of which are offline, source-code-based while others are online, partial-WYSIWYG-based. For more, see Comparison of TeX editors.

Versions

| Filename extension |

.tex |

|---|---|

| Internet media type |

application/x-latex [Note 1] |

| Latest release | LaTeX2e (1994) |

| Type of format | Document file format |

LaTeX2e is the current version of LaTeX, since it replaced LaTeX 2.09 in 1994[24]. As of 2019, LaTeX3, which started in the early 1990s, is under a long-term development project.[25] Planned features include improved syntax, hyperlink support, a new user interface, access to arbitrary fonts and a new documentation.[26]

There are numerous commercial implementations of the entire TeX system. System vendors may add extra features like additional typefaces and telephone support. LyX is a free, WYSIWYM visual document processor that uses LaTeX for a back-end.[27] TeXmacs is a free, WYSIWYG editor with similar functionalities as LaTeX, but with a different typesetting engine.[28] Other WYSIWYG editors that produce LaTeX include Scientific Word on MS Windows., and BaKoMa TeX on Windows, Mac and Linux.

A number of community-supported TeX distributions are available, including TeX Live (multi-platform), teTeX (deprecated in favor of TeX Live, UNIX), fpTeX (deprecated), MiKTeX (Windows), proTeXt (Windows), MacTeX (TeX Live with the addition of Mac specific programs), gwTeX (Mac OS X) (deprecated), OzTeX (Mac OS Classic), AmigaTeX (no longer available), PasTeX (AmigaOS, available on the Aminet repository), and Auto-Latex Equations (Google Docs add-on that supports MathJax LaTeX commands).

Compatibility and converters

LaTeX documents (*.tex) can be opened with any text editor. They consist of plain text and do not contain hidden formatting codes or binary instructions. Additionally, TeX documents can be shared by rendering the LaTeX file to Rich Text Format (*.rtf) or XML. This can be done using the free software programs LaTeX2RTF or TeX4ht. LaTeX can also be rendered to PDF files using the LaTeX extension pdfLaTeX. LaTeX files containing Unicode text can be processed into PDFs with the inputenc package, or by the TeX extensions XeLaTeX and LuaLaTeX.

- HeVeA is a converter written in Ocaml that converts LaTeX documents to HTML5. It is licensed under the Q Public License.[29]

- LaTeX2HTML is a converter written in Perl that converts LaTeX documents to HTML. This way, e.g., scientific papers—primarily typeset for printing—can be placed on the Web for online viewing. It is licensed under GNU GPL v2.[30] The latest updates are available from CTAN.[31]

- LaTeXML is a free, public domain software, written in Perl, which converts LaTeX documents to a variety of structured formats, including HTML5, epub, jats, tei.[32]

- Pandoc is a 'universal document converter' able to transform LaTeX into many different file formats, including HTML5, epub, rtf and docx. It is licensed under GNU GPL v2.[33]

LaTeX has become the de facto standard to typeset mathematical expression in scientific documents.[4][34] Hence, there are several conversion tools focusing on mathematical LaTeX expressions, such as converters to MathML[35] or Computer Algebra System.[36]

- Mathoid is a web-service converter using Node.js that converts math inputs, such as LaTeX, to MathML and picture formats, including SVG and PNG. It is used in Wikipedia to render math.[37]

- TeXZilla[38] is a JavaScript LaTeX to MathML converter. It is one of the fastest LaTeX to MathML converters.[35]

- LaCASt is a converter written in Java that converts a semantic dialect of LaTeX to Maple and Mathematica.[36]

History

LaTeX was created in the early 1980s by Leslie Lamport, when he was working at SRI. He needed to write TeX macros for his own use, and thought that with a little extra effort he could make a general package usable by others. Peter Gordon, an editor at Addison-Wesley, convinced him to write a LaTeX user's manual for publication (Lamport was initially skeptical that anyone would pay money for it);[39] it came out in 1986[2] and sold hundreds of thousands of copies.[39] Meanwhile, Lamport released versions of his LaTeX macros in 1984 and 1985. On 21 August 1989, at a TeX Users Group (TUG) meeting at Stanford, Lamport agreed to turn over maintenance and development of LaTeX to Frank Mittelbach. Mittelbach, along with Chris Rowley and Rainer Schöpf, formed the LaTeX3 team; in 1994, they released LaTeX 2e, the current standard version, and continue working on LaTeX3.[24]

See also

- BibTeX – reference management software typically used with LaTeX

- Formula editor

- Help:Displaying a formula

- List of document markup languages

- List of TeX extensions

- xdvi – software for viewing DVI files while using Unix

Notes

References

- "An introduction to LaTeX". LaTeX project. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Lamport, Leslie (1986). LATEX : a document preparation system. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. ISBN 020115790X. OCLC 12550262.

- "What are TeX, LaTeX and friends?".

- Alexia Gaudeul (March 27, 2006). "Do Open Source Developers Respond to Competition?: The (La)TeX Case Study". SSRN 908946. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Markin, Pablo (1 November 2017). "LaTeX, Open Source Software, Facilitates the Adoption of Open Access by Authors, Repositories and Journals". OpenScience. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "The Definitive, Non-Technical Introduction to LaTeX, Professional Typesetting and Scientific Publishing". Math Vault. 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "Arabic in LaTeX". Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- Leslie Lamport (April 23, 2007). "The Writings of Leslie Lamport: LaTeX: A Document Preparation System". Leslie Lamport's Home Page. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- "LaTeX - A document preparation system". www.latex-project.org. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- The design of LaTeX owes something to earlier markup systems such as Scribe.

- PDF output is common, but TeX can output other formats such as DVI ("Device independent" format). See below for more detail about outputs.

- "Overleaf".

- "Seeveeze".

- "LaTeX Base".

- "Authorea".

- Donald E. Knuth, The TeXbook, Addison–Wesley, Boston, 1986, p. 1.

- Lamport (1994), p 5

- O'Connor, Edward. "TeX and LaTeX logo POSHlets". Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- Taraborelli, Dario. "CSS-driven TeX logos". Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- Walden, David (2005-07-15). "Travels in TeX Land: A Macro, Three Software Packages, and the Trouble with TeX". The PracTeX Journal (3). Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- "The LaTeX project public license". www.latex-project.org. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "pdfTeX - TeX Users Group". www.tug.org. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "XeTeX - TeX Users Group". www.tug.org. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- Scavo, Tom. "TeX, LaTeX, and AMS-LaTeX". Archived from the original on 3 December 1998. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "The LaTeX3 Project". www.latex-project.org. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- Frank Mittelbach, Chris Rowley (January 12, 1999). "The LaTeX3 Project" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- "LyX | What is LyX?". www.lyx.org. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "Welcome to GNU TeXmacs".

- Website http://hevea.inria.fr/

- According to LICENSE file in the source repository.

- "CTAN: Package latex2html". www.ctan.org.

- "LaTeXML A LaTeX to XML/HTML/MathML Converter". dlmf.nist.gov. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- "Pandoc - About pandoc". pandoc.org.

- Knauff, Markus; Nejasmic, Jelica (December 19, 2019). "An Efficiency Comparison of Document Preparation Systems Used in Academic Research and Development". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e115069. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115069. PMID 25526083.

- Schubotz, Moritz; Greiner-Petter, André; Scharpf, Philipp; Meuschke, Norman; Cohl, Howard; Gipp, Bela (2018). "Improving the Representation and Conversion of Mathematical Formulae by Considering their Textual Context". Proc. ACM/IEEE on Joint Conference on Digital Libraries. JCDL. ACM. pp. 233–242. arXiv:1804.04956. doi:10.1145/3197026.3197058.

- Greiner-Petter, André; Schubotz, Moritz; Cohl, Howard; Gipp, Bela (2019). "Semantic preserving bijective mappings for expressions involving special functions between computer algebra systems and document preparation systems". Aslib Journal of Information Management. 71 (3): 415–439. arXiv:1906.11485. doi:10.1108/AJIM-08-2018-0185.

- Schubotz, Moritz; Wicke, Gabriel (2014). "Mathoid: Robust, Scalable, Fast and Accessible Math Rendering for Wikipedia". Intelligent Computer Mathematics - International Conference. CICM. Springer. pp. 224–235. arXiv:1404.6179. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08434-3_17.

- "TeXZilla".

- Lamport, Leslie (23 August 2018). "My Writings" (PDF). pp. 48–49. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

Further reading

- Flynn, Peter (2017) [2002]. Formatting Information: A Beginner's Guide to LaTeX (7th online ed.). Cork: Silmaril. p. 193.

- Griffiths, David F.; Highman, David S. (1997). Learning LaTeX. Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. ISBN 0-89871-383-8.

- Kopka, Helmut; Daly, Patrick W. (2003). Guide to LaTeX (4th ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 0-321-17385-6.

- Lamport, Leslie (1994). LaTeX: A document preparation system: User's guide and reference. illustrations by Duane Bibby (2nd ed.). Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 0-201-52983-1.

- Mittelbach, Frank; Goossens, Michel (2004). The LaTeX Companion (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-36299-6.