Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon (/ˈtɛsɪfɒn/ TESS-if-on; Attic Greek: [ktɛːsipʰɔ̂ːn]; Middle Persian: 𐭲𐭩𐭮𐭯𐭥𐭭 tyspwn or tysfwn,[1] Persian: تیسفون, Greek: Κτησιφῶν, Syriac: ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ[2]) was an ancient city, located on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and about 35 kilometres (22 mi) southeast of present-day Baghdad. Ctesiphon served as a royal capital of the Persian Empire (Iran) in the Parthian and Sasanian eras for over eight hundred years.[3] Ctesiphon remained the capital of the Sasanian Empire until the Muslim conquest of Persia in 651 AD.

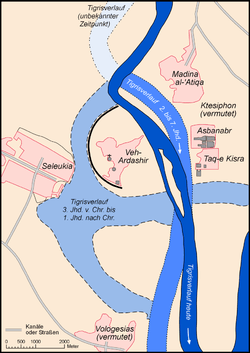

Map of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in the Sassanid era | |

Shown within Iraq | |

| Location | Salman Pak, Baghdad Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 33°5′37″N 44°34′50″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Iranian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1928–1929, 1931–1932, 1960s–1970s |

| Archaeologists | Oscar Reuther, Antonio Invernizzi, Giorgio Gullini |

| Condition | Ruined |

Ctesiphon developed into a rich commercial metropolis, merging with the surrounding cities along both shores of the river, including the Hellenistic city of Seleucia. Ctesiphon and its environs were therefore sometimes referred to as "The Cities" (Aramaic: Mahuza, Arabic: المدائن, al-Mada'in). In the late sixth and early seventh century, it was listed as the largest city in the world by some accounts.[4]

During the Roman–Parthian Wars, Ctesiphon fell three times to the Romans, and later fell twice during Sasanian rule. It was also the site of the Battle of Ctesiphon in 363 AD. After the Muslim invasion the city fell into decay and was depopulated by the end of the eighth century, its place as a political and economic center taken by the Abbasid capital at Baghdad. The most conspicuous structure remaining today is the Taq Kasra, sometimes called the Archway of Ctesiphon.[5]

Names

The Latin name Ctesiphon derives from Ancient Greek Ktēsiphôn (Κτησιφῶν). This is ostensibly a Greek toponym based on a personal name, although it may be a Hellenized form of a local name, reconstructed as Tisfōn or Tisbōn.[6] In Iranian-language texts of the Sasanian era, it is spelled as tyspwn, which can be read as Tīsfōn, Tēsifōn, etc. in Manichaean Parthian 𐫤𐫏𐫘𐫛𐫇𐫗, in Middle Persian 𐭲𐭩𐭮𐭯𐭥𐭭 and in Christian Sogdian (in Syriac alphabet) languages. The New Persian form is Tisfun (تیسفون).

Texts from the Church of the East's synods referred to the city as Qṭēspōn (Syriac: ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ)[2] or some times Māḥôzē (Syriac: ܡܚܘܙ̈ܐ) when referring to the metropolis of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

In modern Arabic, the name is usually Ṭaysafūn (طيسفون) or Qaṭaysfūn (قطيسفون) or as al-Mada'in (المدائن "The Cities", referring to Greater Ctesiphon). "According to Yāqūt [...], quoting Ḥamza, the original form was Ṭūsfūn or Tūsfūn, which was arabicized as Ṭaysafūn."[7] The Armenian name of the city was Tizbon (Տիզբոն). Ctesiphon is first mentioned in the Book of Ezra[8] of the Old Testament as Kasfia/Casphia (a derivative of the ethnic name, Cas, and a cognate of Caspian and Qazvin). It is also mentioned in the Talmud as Aktisfon.[9]

Location

Ctesiphon is located approximately at Al-Mada'in, 32 km (20 mi) southeast of the modern city of Baghdad, Iraq, along the river Tigris. Ctesiphon measured 30 square kilometers, more than twice the surface of 13.7-square-kilometer fourth-century imperial Rome.

The archway of Chosroes (Taq Kasra) was once a part of the royal palace in Ctesiphon and is estimated to date between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD.[10] It is located in what is now the Iraqi town of Salman Pak.

History

Parthian period

Ctesiphon was founded in the late 120s BC. It was built on the site of a military camp established across from Seleucia by Mithridates I of Parthia. The reign of Gotarzes I saw Ctesiphon reach a peak as a political and commercial center. The city became the Empire's capital circa 58 BC during the reign of Orodes II. Gradually, the city merged with the old Hellenistic capital of Seleucia and other nearby settlements to form a cosmopolitan metropolis.[11]

The reason for this westward relocation of the capital could have been in part due to the proximity of the previous capitals (Mithradatkirt, and Hecatompylos at Hyrcania) to the Scythian incursions.[11]

Strabo abundantly describes the foundation of Ctesiphon:

In ancient times Babylon was the metropolis of Assyria; but now Seleucia is the metropolis, I mean the Seleucia on the Tigris, as it is called. Nearby is situated a village called Ctesiphon, a large village. This village the kings of the Parthians were wont to make their winter residence, thus sparing the Seleucians, in order that the Seleucians might not be oppressed by having the Scythian folk or soldiery quartered amongst them. Because of the Parthian power, therefore, Ctesiphon is a city rather than a village; its size is such that it lodges a great number of people, and it has been equipped with buildings by the Parthians themselves; and it has been provided by the Parthians with wares for sale and with the arts that are pleasing to the Parthians; for the Parthian kings are accustomed to spend the winter there because of the salubrity of the air, but they summer at Ecbatana and in Hyrcania because of the prevalence of their ancient renown.[12]

Because of its importance, Ctesiphon was a major military objective for the leaders of the Roman Empire in their eastern wars. The city was captured by Rome five times in its history – three times in the 2nd century alone. The emperor Trajan captured Ctesiphon in 116, but his successor, Hadrian, decided to willingly return Ctesiphon in 117 as part of a peace settlement. The Roman general Avidius Cassius captured Ctesiphon in 164 during another Parthian war, but abandoned it when peace was concluded. In 197, the emperor Septimius Severus sacked Ctesiphon and carried off thousands of its inhabitants, whom he sold into slavery.

Sasanian period

By 226, Ctesiphon was in the hands of the Sasanian Empire, who also made it their capital and had laid an end to the Parthian dynasty of Iran. Ctesiphon was greatly enlarged and flourished during their rule, thus turning into a metropolis, which was known by in Arabic as al-Mada'in, and in Aramaic as Mahoze.[13] The oldest inhabited places of Ctesiphon were on its eastern side, which in Islamic Arabic sources is called "the Old City" (مدينة العتيقة Madīnah al-'Atīqah), where the residence of the Sasanians, known as the White Palace (قصر الأبيض), was located. The southern side of Ctesiphon was known as Asbānbar or Aspānbar, which was known by its prominent halls, riches, games, stables, and baths. Taq Kasra was located in the latter.[13][14]

The western side was known as Veh-Ardashir (meaning "the good city of Ardashir" in Middle Persian), known as Mahoza by the Jews, Kokhe by the Christians, and Behrasir by the Arabs. Veh-Ardashir was populated by many wealthy Jews, and was the seat of the church of the Nestorian patriarch. To the south of Veh-Ardashir was Valashabad.[13] Ctesiphon had several other districts which were named Hanbu Shapur, Darzanidan, Veh Jondiu-Khosrow, Nawinabad and Kardakadh.[13]

Severus Alexander advanced towards Ctesiphon in 233, but as corroborated by Herodian, his armies suffered a humiliating defeat against Ardashir I.[15] In 283, emperor Carus sacked the city uncontested during a period of civil upheaval. In 295, emperor Galerius was defeated outside the city. However, he returned a year later with a vengeance and won a victory which ended in the fifth and final capture of the city by the Romans in 299. He returned it to the Persian king Narses in exchange for Armenia and western Mesopotamia. In c. 325 and again in 410, the city, or the Greek colony directly across the river, was the site of church councils for the Church of the East.

.png)

After the conquest of Antioch in 541, Khosrau I built a new city near Ctesiphon for the inhabitants he captured. He called this new city Weh Antiok Khusrau, or literally, "better than Antioch Khosrau built this."[16] Local inhabitants of the area called the new city Rumagan, meaning "town of the Romans" and Arabs called the city al-Rumiyya. Along with Weh Antiok, Khosrau built a number of fortified cities.[17] Khosrau I deported 292,000 citizens, slaves, and conquered people to this new city in 542.[18]

In 590, a member of the House of Mihran, Bahram Chobin repelled the newly ascended Sasanian ruler Khosrau II from Iraq, and conquered the region. One year later, Khosrau II, with aid from the Byzantine Empire, reconquered his domains. During his reign, some of the great fame of al-Mada'in decreased, due to the popularity of Khosrau's new winter residence, Dastagerd.[19] In 627, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius surrounded the city, the capital of the Sassanid Empire, leaving it after the Persians accepted his peace terms. In 628, a deadly plague hit Ctesiphon, al-Mada'in and the rest of the western part of the Sasanian Empire, which even killed Khosrau's son and successor, Kavadh II.[19]

In 629, Ctesiphon was briefly under the control of Mihranid usurper Shahrbaraz, but the latter was shortly assassinated by the supporters of Khosrau II's daughter Borandukht. Ctesiphon then continued to be involved in constant fighting between two factions of the Sasanian Empire, the Pahlav (Parthian) faction under the House of Ispahbudhan and the Parsig (Persian) faction under Piruz Khosrow.

Downfall of the Sasanians and the Islamic conquests

In the mid-630s, the Muslim Arabs, who had invaded the territories of the Sasanian Empire, defeated them during a great battle known as the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah.[13] The Arabs then attacked Ctesiphon, and occupied it in early 637.

The Muslim military officer Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas quickly seized Valashabad and made a peace treaty with the inhabitants of Weh Antiok Khusrau and Veh-Ardashir. The terms of the treaty were that the inhabitants of Weh Antiok Khusrau were allowed to leave if they wanted to, but if they did not, they were forced to acknowledge Muslim authority, and also pay tribute (jizya). Later on, when the Muslims arrived at Ctesiphon, it was completely desolated, due to flight of the Sasanian royal family, nobles, and troops. However, the Muslims had managed to take some of troops captive, and many riches were seized from the Sasanian treasury and were given to the Muslim troops.[13] Furthermore, the throne hall in Taq Kasra was briefly used as a mosque.[20]

Still, as political and economic fortune had passed elsewhere, the city went into a rapid decline, especially after the founding of the Abbasid capital at Baghdad in the 8th century, and soon became a ghost town. Caliph Al-Mansur took much of the required material for the construction of Baghdad from the ruins of Ctesiphon. He also attempted to demolish the palace and reuse its bricks for his own palace, but he desisted only when the undertaking proved too vast.[21] Al-Mansur also used the al-Rumiya town as the Abbasid capital city for a few months.[22]

It is believed to be the basis for the city of Isbanir in One Thousand and One Nights.

Modern era

The ruins of Ctesiphon were the site of a major battle of World War I in November 1915. The Ottoman Empire defeated troops of Britain attempting to capture Baghdad, and drove them back some 40 miles (64 km) before trapping the British force and compelling it to surrender.

Population and religion

Under Sasanian rule, the population of Ctesiphon was heavily mixed: it included Arameans, Persians, Greeks and Assyrians. Several religions were also practiced in the metropolis, which included Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism. In 497, the first Nestorian patriarch Mar Babai I, fixed his see at Seleucia-Ctesiphon, supervising their mission east, with the Merv metropolis as pivot. The population also included Manicheans, a Dualist church, who continued to be mentioned in Ctesiphon during Umayyad rule fixing their 'patriarchate of Babylon' there.[13] Much of the population fled from Ctesiphon after the Arab capture of the metropolis. However, a portion of Persians remained there, and some important figures of these people are known to have provided Ali with presents, which he, however, refused to take. [13] In the ninth century, the surviving Manicheans fled and displaced their patriarchate up the Silk road, in Samarkand.[23]

Archaeology

A German Oriental Society led by Oscar Reuther excavated at Ctesiphon in 1928–29 mainly at Qasr bint al-Qadi on the western part of the site.[24][25][26][27] In winter of 1931–1932 a joint expedition of the German State Museums (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) and The Metropolitan Museum of Art continued excavations at the site, focusing on the areas of Ma'aridh, Tell Dheheb, the Taq-i Kisra, Selman Pak and Umm ez-Za'tir under the direction of Ernst Kühnel.[28]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an Italian team from the University of Turin directed by Antonio Invernizzi and Giorgio Gullini worked at the site, which they identified not as Ctesiphon but as Veh Ardashir. Work mainly concentrated on restoration at the palace of Khosrau II.[29][30][31][32][33][34] In 2013, the Iraqi government contracted to restore the Taq Kasra, as a tourist attraction.[35]

Gallery

- Ctesiphon Gallery

1824 drawing by Captain Hart

1824 drawing by Captain Hart Remains of Taq Kasra in 2008.

Remains of Taq Kasra in 2008. 1923 Iraqi postage stamp, featuring the arch

1923 Iraqi postage stamp, featuring the arch

See also

- Opis

- Persian Empire

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Rachae

References

- Kröger, Jens. "Ctesiphon". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Ctesiphon — ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified July 28, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/58.

- "Ctesiphon: An Ancient Royal Capital in Context". Smithsonian. September 15, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- "Largest Cities Through History". geography.about.com. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Eventually no less than four Sasanian rulers were quoted as its builders: Shapur I (241–273), Shapur II (310–379), Chosroes I Anushirvan (531–579) and Chosroes II Parvez (590–628). Kurz, Otto (1941). "The Date of the Ṭāq i Kisrā". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (New Series). 73 (1): 37–41. JSTOR 25221709.

- E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936, Vol. 2 (Brill, 1987: ISBN 90-04-08265-4), p. 75.

- Kröger, Jens (1993), "Ctesiphon", Encyclopedia Iranica, 6, Costa Mesa: Mazda, archived from the original on 2009-01-16

- Ezra 8:17

- Talmud Bavli Tractate Gittin. pp. 6A.

- Farrokh, K. (2007). The rise of Ctesiphon and the Silk Route. In Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War (p. 240).

- Farrokh, K. (2007). The rise of Ctesiphon and the Silk Route. In Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War (p. 125).

- "LacusCurtius • Strabo's Geography — Book XVI Chapter 1, 16". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Morony 2009.

- Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. BRILL. p. 76a. ISBN 9789004097919.

- Farrokh, K. (2007). The rise of Ctesiphon and the Silk Route. In Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War (p. 185).

- Dingas, Winter 2007, 109

- Frye 1993, 259

- Christensen (1993). The Decline of Iranshahr: Irrigation and Environments in the History of the Middle East, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1500. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-259-5.

- Shapur Shahbazi 2005.

- Reade, Dr Julian (1999). Scarre, Chris, ed. The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient world The Great Monuments and How they were Built. Thames & Hudson. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-500-05096-1.

- Bier, L. (1993). The Sassanian Palaces and their Influence in Early Islam. In Ars Orientalis, 23, 62-62.

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1895). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society. p. 40.

- John van Schaik, Ketters. Een geschiedenis van de Kerk, Leuven, 2016

- Schippmann, K. (1980). "Ktesiphon-Expedition im Winter 1928/29". Grundzüge der parthischen Geschichte (in German). Darmstadt. ISBN 3-534-07064-X.

- Meyer, E. (1929). "Seleukia und Ktesiphon". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft zu Berlin. 67: 1–26.

- Reuther, O. (1929). "The German Excavations at Ctesiphon". Antiquity. 3 (12): 434–451. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00003781.

- Upton, J. (1932). "The Expedition to Ctesiphon 1931–1932". Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 27: 188–197.

- Fowlkes-Childs, Blair. “Ctesiphon.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ctes/hd_ctes.htm (July 2016)

- G. Gullini and A. Invernizzi, First Preliminary Report of Excavations at Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Season 1964, Mesopotamia, vol. I, pp. 1–88, 1966

- G. Gullini and A. Invernizzi, Second Preliminary Report of Excavations at Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Season 1965, Mesopotamia, vol. 2, 1967

- G. Gullini and A. Invernizzi, Third Preliminary Report of Excavations at Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Season 1966, Mesopotamia, vol. 3–4, 1968–69

- G. Gullini and A. Invernizzi, Fifth Preliminary Report of Excavations at Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Season 1969, Mesopotamia, vol. 5–6, 1960–71

- G. Gullini and A. Invernizzi, Sixth Preliminary Report of Excavations at Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Seasons 1972/74, Mesopotamia, vol. 5–6, 1973–74

- G. Gullini and A. Invernizzi, Seventh Preliminary Report of Excavations at Seleucia and Ctesiphon. Seasons 1975/76, Mesopotamia, vol. 7, 1977

- "Iraq to restore ancient Arch of Ctesiphon to woo back tourists". rawstory.com. May 30, 2013.

Bibliography

- M. Streck, Die alte Landschaft Babylonien nach den arabischen Geographen, 2 vols. (Leiden, 1900–1901).

- M. Streck, "Seleucia und Ktesiphon," Der Alte Orient, 16 (1917), 1–64.

- A. Invernizzi, "Ten Years Research in the al-Madain Area, Seleucia and Ctesiphon," Sumer, 32, (1976), 167–175.

- Luise Abramowski, "Der Bischof von Seleukia-Ktesiphon als Katholikos und Patriarch der Kirche des Ostens," in Dmitrij Bumazhnov u. Hans R. Seeliger (hg), Syrien im 1.-7. Jahrhundert nach Christus. Akten der 1. Tübinger Tagung zum Christlichen Orient (15.-16. Juni 2007). (Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 2011) (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum / Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity, 62),

- Morony, Michael (2009). "MADĀʾEN". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Amedroz, Henry F.; Margoliouth, David S., eds. (1921). The Eclipse of the ‘Abbasid Caliphate. Original Chronicles of the Fourth Islamic Century, Vol. V: The concluding portion of The Experiences of Nations by Miskawaihi, Vol. II: Reigns of Muttaqi, Mustakfi, Muti and Ta'i. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rekaya, M. (1991). "al-Maʾmūn". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 331–339. ISBN 90-04-08112-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zarrinkub, Abd al-Husain (1975). "The Arab conquest of Iran and its aftermath". The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–57. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bosworth, C. E. (1975). "Iran under the Buyids". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–305. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kröger, Jens (1993). "CTESIPHON". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. pp. 446–448.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2005). "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 30 March 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ctesiphon. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Ctesiphon. |

- Ctesiphon and Taq Kasra photo gallery

- Ctesiphon Exhibition at German State Museum (Video)

- Livius.org: Ctesiphon

- Ctesiphon (profile at the Metropolitan Museum of Art)