Black Dragon Society

The Black Dragon Society (Kyūjitai; 黑龍會; Shinjitai: 黒竜会, kokuryūkai), or Amur River Society, was a prominent paramilitary, ultranationalist group in Japan.

| Formation | 1901 |

|---|---|

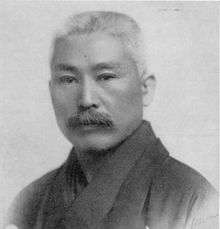

| Founder | Uchida Ryohei |

| Founded at | Japan |

| Type | Political |

| Location |

|

| Fields | Politics |

History

The Kokuryūkai was founded in 1901 by martial artist Uchida Ryohei as a successor to his mentor Mitsuru Tōyama's Gen'yōsha.[1] Its name is derived from the translation of the Amur River, which is called Heilongjiang or "Black Dragon River" in Chinese (黑龍江?), read as Kokuryū-kō in Japanese. Its public goal was to support efforts to keep the Russian Empire north of the Amur River and out of East Asia.

The Kokuryūkai initially made strenuous efforts to distance itself from the criminal elements of its predecessor, the Gen'yōsha. As a result, its membership included Cabinet Ministers and high-ranking military officers as well as professional secret agents. However, as time passed, it found the use of criminal activities to be a convenient means to an end for many of its operations.

The Society published a journal, and operated an espionage training school, from which it dispatched agents to gather intelligence on Russian activities in Russia, Manchuria, Korea and China. Ikki Kita was sent to China as a special member of the organization. It also pressured Japanese politicians to adopt a strong foreign policy. The Kokuryūkai also supported Pan-Asianism, and lent financial support to revolutionaries such as Sun Yat-sen and Emilio Aguinaldo.

During the Russo-Japanese War, annexation of Korea and Siberian Intervention, the Imperial Japanese Army made use of the Kokuryūkai network for espionage, sabotage and assassination. They organized Manchurian guerrillas against the Russians from the Chinese warlords and bandit chieftains in the region, the most important being Marshal Chang Tso-lin. The Black Dragons waged a very successful psychological warfare campaign in conjunction with the Japanese military, spreading disinformation and propaganda throughout the region. They also acted as interpreters for the Japanese army.

The Kokuryūkai assisted the Japanese spy, Colonel Motojiro Akashi. Akashi, who was not directly a member of the Black Dragons, ran successful operations in China, Manchuria, Siberia and established contacts throughout the Muslim world. These contacts in Central Asia were maintained through World War II. The Black Dragons also formed close contact and even alliances with Buddhist sects throughout Asia.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Kokuryūkai evolved into more of a mainstream political organization, and publicly attacked liberal and leftist thought. Although it never had more than several dozen members at any one time during this period, the close ties of its membership to leading members of the government, military and powerful business leaders gave it a power and influence far greater than most other ultranationalist groups. In 1924, retired naval captain Yutaro Yano and his associates within the Black Dragon Society invited Oomoto leader Onisaburo Deguchi on a journey to Mongolia. Onisaburo led a group of Oomoto disciples, including Aikido founder Morihei Ueshiba.

Initially directed only against Russia, in the 1930s, the Kokuryūkai expanded its activities around the world, and stationed agents in such diverse places as Ethiopia, Turkey, Morocco, throughout Southeast Asia and South America, as well as Europe and the United States.

The Kokuryūkai was officially disbanded by order of the American Occupation authorities in 1946. According to Brian Daizen Victoria's book, Zen War Stories, the Black Dragon Society was reconstituted in 1961 as the Black Dragon Club (Kokuryū-Kurabu.) The Club never had more than 150 members to succeed in the goals of the former Black Dragon Society.[2]

Activities in the United States

The organization was an influence on seditious black nationalists, aiming to foment racial unrest.[3] African-Americans liked the symbolism of the black dragon fighting against the American eagle and British lion.[4]

As part of that effort, the Black Dragon Society sent their agent, Satokata Takahashi, to promote Pan-Asianism and claim that Japan would treat them as equals.[5] He would become a patron of Elijah Muhammed and the Nation of Islam, as well as the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World.[5] Sankichi Takahashi may have also been a member.

Mittie Maude Lena Gordon's Peace Movement of Ethiopia claimed to be affiliated with the Kokuryūkai.[4]

On March 27, 1942, FBI agents arrested members of the Black Dragon Society in the San Joaquin Valley, California.[6]

In the Manzanar Internment Camp, a small group of pro-Imperial Japanese flew Black Dragon flags and intimidated other Japanese inmates.[7][8]

See also

Notes

- Kaplan, David (2012). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-520-27490-7.

- Victoria, Brian Daizen, Zen War Stories, Routledge Curson 2003, p. 61

- "U.S. At War: Takcihashi's Blacks". Time. October 5, 1942. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Reginald Kearney, African American Views of the Japanese: Solidarity or Sedition?, SUNY Press 1998, p. 77.

- Jones, David (May 17, 2014). "Chinese Triads, Japanese Black Dragons & Hidden Paths of Power". New Dawn. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- 1942 World War II Chronology Archived 2007-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Burton, Jeffery F., Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites, University of Washington Press 2002, p. 172

- Inada, Lawson Fusao & the California Historical Society, Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience, Heyday 2000, pp. 161-162

References

- The Encyclopedia of Espionage by Norman Polmar and Thomas B. Allen (ISBN 0-517-20269-7)

- Deacon, Richard: A History of the Japanese Secret Service, Berkley Publishing Company, New York, 1983, ISBN 0-425-07458-7

- Jacob, Frank: Die Thule-Gesellschaft und die Kokuryûkai: Geheimgesellschaften im global-historischen Vergleich, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg, 2012, ISBN 978-3826049095

- Jacob, Frank (ed.): Geheimgesellschaften: Kulturhistorische Sozialstudien: Secret Societies: Comparative Studies in Culture, Society and History, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3826049088

- Jacob, Frank: Japanism, Pan-Asianism and Terrorism: A Short History of the Amur Society (The Black Dragons) 1901-1945, Academica Press, Palo Alto 2014, ISBN 978-1936320752

- Kaplan, David; Dubro, Alec (2004), Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld, pp. 18–21, ISBN 0520274903

- Saaler, Sven: "The Kokuryûkai, 1901-1920," in Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman (eds.), Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History Vol. I. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2011, pp. 121-132.

- Saaler, Sven: “The Kokuryûkai (Black Dragon Society) and the Rise of Nationalism, Pan-Asianism, and Militarism in Japan, 1901-1925,” International Journal of Asian Studies 11/2 (2014), pp. 125-160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147959141400014X