Kinzua Bridge

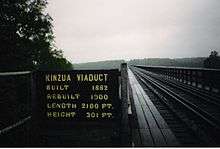

The Kinzua Bridge or the Kinzua Viaduct (/ˈkɪnzuː/,[2] /-zuːə/) was a railroad trestle that spanned Kinzua Creek in McKean County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The bridge was 301 feet (92 m) tall and 2,052 feet (625 m) long. Most of its structure collapsed during a tornado in July 2003.

Kinzua Bridge | |

|---|---|

The bridge before its collapse | |

| Coordinates | 41°45′40″N 78°35′19″W |

| Crosses | Kinzua Creek |

| Locale | McKean, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Other name(s) | Kinzua Viaduct |

| Named for | Kinzua, Seneca for "fish on a spear" |

| Maintained by | Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Railroad bridge |

| Total length | 2,052 ft (625 m)[1] |

| Width | 10 ft (3.0 m) |

| Height | 301 ft (92 m)[1] |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Elmira Bridge Company |

| Built | 1882 |

| Collapsed | July 21, 2003 |

| NRHP reference No. | 77001511 |

| Added to NRHP | August 29, 1977 |

Kinzua Bridge Location of the Kinzua Bridge in Pennsylvania  Kinzua Bridge Location in United States | |

The bridge was originally built from wrought iron in 1882 and was billed as the "Eighth Wonder of the World", holding the record as the tallest railroad bridge in the world for two years. In 1900, the bridge was dismantled and simultaneously rebuilt out of steel to allow it to accommodate heavier trains. It stayed in commercial service until 1959 and was sold to the Government of Pennsylvania in 1963, becoming the centerpiece of a state park.

Restoration of the bridge began in 2002, but before it was finished, a tornado struck the bridge in 2003, causing a large portion of the bridge to collapse. Corroded anchor bolts holding the bridge to its foundations failed, contributing to the collapse.

Before its collapse, the Kinzua Bridge was ranked as the fourth-tallest railway bridge in the United States.[3] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1982. The ruins of the Kinzua Bridge are in Kinzua Bridge State Park off U.S. Route 6 near the borough of Mount Jewett, Pennsylvania.

First construction and service

In 1882, Thomas L. Kane, president of the New York, Lake Erie and Western Railway (NYLE&W), was faced with the challenge of building a branch line off the main line in Pennsylvania, from Bradford south to the coal fields in Elk County.[4][5] The fastest way to do so was to build a bridge to cross the Kinzua Valley. The only other alternative to building a bridge would have been to lay an additional 8 miles (13 km) of track over rough terrain.[6] When built, the bridge was larger than any that had been attempted, and over twice as large as the largest similar structure at the time: the Portage Bridge over the Genesee River in western New York.[7]

The first Kinzua Bridge was built by a crew of 40 from 1,552 short tons (1,408 t) of wrought iron in just 94 working days, between May 10 and August 29, 1882.[1][8][9] The reason for the short construction time was that scaffolding was not used in the bridge's construction; instead a gin pole was used to build the first tower, then a traveling crane was built atop it and used in building the second tower.[8][10] The process was then repeated across all 20 towers.[4]

The bridge was designed by the engineer Octave Chanute and was built by the Phoenix Iron Works, which specialized in producing patented, hollow iron tubes called "Phoenix columns".[4] Because of the design of these columns, it was often mistakenly believed that the bridge had been built out of wooden poles.[10] The bridge's 110 sandstone masonry piers were quarried from the hillside used for the foundation of the bridge.[1][4] The tallest tower had a base that was 193 feet (59 m) wide.[1] The bridge was designed to support a load of 266 short tons (241 t),[5] and was estimated to cost between $167,000 and $275,000.[8][11][12]

On completion, the bridge was the tallest and longest railroad bridge in the world and was advertised as the "Eighth Wonder of the World".[3][10] Six of the bridge's 20 towers were taller than the Brooklyn Bridge.[1] Excursion trains from as far away as Buffalo, New York, and Pittsburgh would come just to cross the Kinzua Bridge,[10] which held the height record until the Garabit viaduct, 401 feet (122 m) tall, was completed in France in 1884.[13] Trains crossing the bridge were restricted to a speed of 5 miles per hour (8.0 km/h) because the locomotive, and sometimes the wind, caused the bridge to vibrate.[10] People sometimes visited the bridge in hopes of finding the loot of a bank robber, who supposedly hid $40,000 in gold and currency under or near it.[4][10]

Second construction and service

By 1893, the NYLE&W had gone bankrupt and was merged with the Erie Railroad, which became the owner of the bridge.[13] By the start of the 20th century, locomotives were almost 85 percent heavier, and the iron bridge could no longer safely carry trains.[1] The last traffic crossed the old bridge on May 14, 1900, and removal of the old iron began on May 24.

The new bridge was designed by C.R. Grimm and was built by the Elmira Bridge Company out of 3,358 short tons (3,046 t) of steel, at a cost of $275,000.[14] Construction began on May 26, starting from both ends of the old bridge. A crew of between 100 and 150 worked 10-hour days for almost four months to complete the new steel frame. Two Howe truss "timber travelers", each 180 feet (50 m) long and 16 feet (5 m) deep, were used to build the towers.[15] Each "traveler" was supported by a pair of the original wrought-iron towers, separated by the one that was to be replaced. After the middle tower was demolished and a new steel one built in its place, the traveler was moved down the line by one tower and the process was repeated. Construction of each new tower and the spans adjoining it took one week to complete.[15] The bolts used to hold the towers to the anchor blocks were reused from the first bridge, which would eventually play a major role in the bridge's demise.[16] Grimm, the designer of the bridge, later admitted that the bolts should have been replaced.[17]

The Kinzua Viaduct reopened to traffic on September 25, 1900. The new bridge was able to safely accommodate one of the largest steam locomotives in the world, the 511-short-ton (464 t) Big Boy.[18][1][13][14] The Erie Railroad maintained a station at the Kinzua Viaduct. Constructed between 1911 and 1916,[19] the station was not manned by an agent.[20] The station was closed sometime between 1923 and 1927.[21][22]

Train crews would sometimes play a trick on a brakeman on his first journey on the line. When the train was a short distance from the bridge, the crew would send the brakeman over the rooftops of the cars to check on a small supposed problem. As the train crossed the bridge, the rookie "suddenly found himself terrified, staring down three hundred feet (90 m) from the roof of a rocking boxcar".[13] Even after being reconstructed the bridge still had a speed limit of 5 miles per hour (8 km/h). As the bridge aged, heavy trains pulled by two steam locomotives had to stop so the engines could cross the bridge one at a time. Diesel locomotives were lighter and did not face that limit; the bridge was last crossed by a steam locomotive on October 5, 1950.[13]

The Erie Railroad obtained trackage rights on the nearby Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) line in the late 1950s, which allowed it to bypass the aging Kinzua Bridge. Regular commercial service ended on June 21, 1959, and the Erie sold the bridge to the Kovalchick Salvage Company of Indiana, Pennsylvania, for $76,000.[14] The bridge was reopened for one day in October 1959 when a wreck on the B&O line forced trains to be rerouted across the bridge.[13] According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, the Kinzua Bridge "was a critical structure in facilitating the transport of coal from Northwestern Pennsylvania to the Eastern Great Lakes region, and is credited with causing an increase in coal mining that led to significant economic growth."[1]

State park

Nick Kovalchick, head of the Kovalchick Salvage Company, which then owned the bridge, was reluctant to dismantle it. On seeing it for the first time he is supposed to have said "There will never be another bridge like this."[23] Kovalchick worked with local groups who wanted to save the structure, and Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton signed a bill into law on August 12, 1963, to purchase the bridge and nearby land for $50,000 and create Kinzua Bridge State Park.[14][24] The deed for the park's 316 acres (128 ha) was recorded on January 20, 1965, and the park was opened to the public in 1970.[24]

An access road to the park was built in 1974, and new facilities there included a parking lot, drinking water and toilets, and installation of a fence on the bridge deck.[24] There was an official ribbon cutting ceremony on July 5, 1975, for the park, which "was and is unique in the park system" since "its centerpiece is a man-made structure".[23] The bridge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 29, 1977,[25] and was named to the National Register of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks by the American Society of Civil Engineers on June 26, 1982.[24]

The Knox and Kane Railroad (KKRR) operated sightseeing trips from Kane through the Allegheny National Forest and over the Kinzua Bridge from 1987 until the bridge was closed in 2002.[26] In 1988 it operated the longest steam train excursion in the United States, a 97-mile (156 km) round trip to the bridge from the village of Marienville in Forest County, with a stop in Kane. The New York Times described being on the bridge as "more akin to ballooning than railroading" and noted "You stare straight out with nothing between you and an immense sea of verdure a hundred yards [91 m] below."[27] The railroad still operated excursions through the forest and stopped at the bridge's western approach until October 2004.[26]

As of 2009, Kinzua Bridge State Park is a 329-acre (133 ha) Pennsylvania state park surrounding the bridge and the Kinzua Valley. The park is located off of U.S. Route 6 north of Mount Jewett in Hamlin and Keating Townships. A scenic overlook within the park allows views of the fallen bridge and of the valley, and is also a prime location to view the fall foliage in mid-October.[28] The park has a shaded picnic area with a centrally located modern restroom.[6] Before the bridge's collapse, visitors were allowed on or under the bridge and hiking was allowed in the valley around the bridge.[6] In September 2002 the bridge was closed even to pedestrian traffic.[9] About 100 acres (40 ha) of Kinzua Bridge State Park are open to hunting. Common game species are turkey, bear and deer.[6]

Destruction

Since 2002, the Kinzua Bridge had been closed to all "recreational pedestrian and railroad usage" after it was determined that the structure was at risk to high winds.[6] Engineers had determined that during high winds, the bridge's center of gravity could shift, putting weight onto only one side of the bridge and causing it to fail.[6] An Ohio-based bridge construction and repair company had started work on restoring the Kinzua Bridge in February 2003.[6]

On July 21, 2003, construction workers had packed up and were starting to leave for the day when a storm arrived.[29] A tornado within the storm struck the Kinzua Bridge, snapping and uprooting nearby trees, as well as causing 11 of the 20 bridge towers to collapse. There were no human deaths or injuries. The tornado was produced by a mesoscale convective system (MCS), a complex of strong thunderstorms, that had formed over an area that included eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, western New York, and southern Ontario.[30] The MCS traveled east at around 40 miles per hour (60 km/h). As the MCS crossed northwestern Pennsylvania, it formed into a distinctive comma shape. The northern portion of the MCS contained a long-lived mesocyclone, a thunderstorm with a rotating updraft that is often conducive to tornados.[31]

At approximately 15:20 EDT (19:20 UTC), the tornado touched down in Kinzua Bridge State Park, 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Kinzua Bridge. The tornado, classified as F1 on the Fujita scale, passed by the bridge and continued another 2.5 miles (4 km) before it lifted. It touched down again 2 miles (3 km) from Smethport and traveled another 3 miles (4.8 km) before finally dissipating. It was estimated to have been 1⁄3-mile (540 m) wide and it left a path 3.5 miles (5.6 km) long.[32] The same storm also spawned an F3 tornado in nearby Potter County.[33]

When the tornado touched down, the winds had increased to at least 94 miles per hour (151 km/h) and were coming from the east, perpendicular to the bridge, which ran north–south. An investigation determined that Towers 10 and 11 had collapsed first, in a westerly direction.[34] Meanwhile, Towers 12 through 14 had actually been picked up off their foundations, moved slightly to the northwest and set back down intact and upright, held together by only the railroad tracks on the bridge. Next towers four through nine collapsed to the west, twisting clockwise, as the tornado started to move northward.[34] As it moved north, inflow winds came in from the south and caused Towers 12, 13, and 14 to finally collapse towards the north, twisting counterclockwise.[34]

The failures were caused by the badly rusted base bolts holding the bases of the towers to concrete anchor blocks embedded into the ground.[6] An investigation determined that the tornado had a wind speed of at least 94 miles per hour (151 km/h), which applied an estimated 90 short tons-force (800 kN) of lateral force against the bridge.[35] The investigation also hypothesized that the whole structure oscillated laterally four to five times before fatigue started to cause the base bolts to fail. The towers fell intact in sections and suffered damage upon impact with the ground.[36] The century-old bridge was destroyed in less than 30 seconds.[37]

Aftermath

The state decided not to rebuild the Kinzua Bridge, which would have cost an estimated $45 million. Instead, it was proposed that the ruins be used as a visitor attraction to show the forces of nature at work.[37] Kinzua Bridge State Park had attracted 215,000 visitors annually before the bridge collapsed,[38] and was chosen by the Pennsylvania Bureau of Parks for its list of "Twenty Must-See Pennsylvania State Parks".[39] The viaduct and its collapse were featured in the History Channel's Life After People as an example of how corrosion and high winds would eventually lead to the collapse of any steel structure.[40] The bridge was removed from the National Register of Historic Places on July 21, 2004.[41]

The Knox and Kane Railroad was forced to suspend operations in October 2004 after a 75 percent decline in the number of passengers, possibly brought about by the collapse of the Kinzua Bridge.[42] The Kovalchick Corporation bought the Knox and Kane's tracks and all other property owned by the railroad, including the locomotives and rolling stock. The Kovalchick Corporation also owns the East Broad Top Railroad and was the company that owned the Kinzua Bridge before selling it to the state in 1963.[42] The company disclosed plans in 2008 to remove the tracks and sell them for scrap. The right-of-way would then be used to establish a rail trail.[42]

Pennsylvania released $700,000 to design repairs on the remaining towers and plan development of the new park facilities in June 2005.[43] In late 2005, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) put forward an $8 million proposal for a new observation deck and visitors' center, with plans to allow access to the bridge and a hiking trail giving views of the fallen towers.[37] The Kinzua Sky Walk was opened on September 15, 2011 in a ribbon-cutting ceremony.[44] The Sky Walk consists of a pedestrian walkway to an observation deck with a glass floor at the end of the bridge that allows views of the bridge and the valley directly below. The walkway cost $4.3 million to construct, but is estimated to bring in $11.5 million in tourism revenue for the region.[45]

See also

- List of bridge failures

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania

- List of Erie Railroad structures documented by the Historic American Engineering Record

- National Register of Historic Places listings in McKean County, Pennsylvania

- Tay Bridge disaster

- Tornadoes of 2003

References

Notes

- "Kinzua Railway Viaduct". Historic Landmarks. American Society of Civil Engineers. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 223.

- "Tornado Tears Down Historic Kinzua Viaduct". Trains. 63 (10): 25. October 2003.

- Linda Devlin (Producer) (2004). Tracks across the sky (DVD). Bradford, Pennsylvania: Allegheny National Forest Vacation Bureau. OCLC 57046003.

- "Removal of Kinzua Viaduct" (PDF). The New York Times. August 21, 1890. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- "Kinzua Bridge State Park". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- Packard 1977, sec. 8.

- Packard 1977, sec. 7.

- Associated Press (July 22, 2003). "High Winds Topple Historic Railroad Bridge". Pittsburgh Post–Gazette. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- Thornton, W. George (August 1949). "Tracks across the Sky". Erie Railroad Magazine: 4–7.

- "Notable new bridges". Railway World. 32: 77. January 28, 1888.

- "The Kinzua Viaduct". Engineering. 34: 613. December 29, 1882.

- "Kinzua Viaduct". Historical Markers. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. 2003. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- Associated Press (December 22, 2002). "Officials fear popular Pa. tourist attraction is near collapse". USA Today. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Packard 1977, sec. 7, p. 1.

- Gannett Fleming (December 2003). "Appendix E: Structural Analysis". Report on the July 21st collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct (PDF) (Report). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- "Discussion on the Kinzua Viaduct". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. American Society of Civil Engineers: 63. December 1901. ISSN 0066-0604.

- Packard 1977, sec. 8, p. 1.

- "Erie Time Tables" (PDF). Jersey City, New Jersey: Erie Railroad. August 1911. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- "List of Station Names and Numbers", Baggage Department, Jersey City, New Jersey: Erie Railroad, May 1, 1916

- Erie Railroad With Branches and Connections (Map). Cartography by M.B. Brown. New York City: P & B Company. 1923. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- "Erie Railroad Time Tables" (PDF). Jersey City, New Jersey: Erie Railroad. August 21, 1927. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- Cupper, Dan (1993). Our Priceless Heritage: Pennsylvania's State Parks 1893–1993. Harrisburg: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of State Parks. pp. 48, 49, 55. ISBN 0-89271-056-X.

- Forrey, William C. (1984). History of Pennsylvania's State Parks. Harrisburg: Bureau of State Parks, Office of Resources Management, Department of Environmental Resources, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. OCLC 17824084.

- United States Department of the Interior; National Park Service (February 6, 1979). "National Register of Historic Places: Annual Listing of Historic Properties" (PDF). Federal Register. National Archives of the United States. 44 (26): 7577. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Milliron, Kyle (September 24, 2008). "Knox & Kane Railroad to sell entire inventory during auction". The Bradford Era. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- Behrman, Dan (May 8, 1988). "Steaming Through Pennsylvania: From Amish country westward, old rail lines offer excursions to mines and picnic grounds". The New York Times. p. XX14. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- McKay, Gretchen (September 15, 2013). "Kinzua colors: Reborn bridge offers spectacular views of fall foliage". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Gannett Fleming (December 2003). "Appendix D: Eyewitness Accounts Construction Crew of the W.M. Brode Company". Report on the July 21st Collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct (PDF) (Report). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 22, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Leech, McHaugh & Dicarlantonio 2005, p. 5.

- Markowski, Paul (December 2003). "Meteorological Aspects of the 21 July 2003 Kinzua Viaduct Storm". Report on the July 21st collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct (PDF) (Report). Department of Meteorology, Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 22, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- "Event Record Details". National Climatic Data Center. July 21, 2003. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- "Event Record Details". National Climatic Data Center. July 21, 2003. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- Gannett Fleming (December 2003). "Initiation of Failure". Report on the July 21st collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct (Report). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- Gannett Fleming (December 2003). "Mechanics of Collapse". Report on the July 21st collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct (Report). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Gannett Fleming (December 2003). "Executive Summary". Report on the July 21st collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct (Report). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Genshiemer, Lisa (Fall 2005). "Hope for the Kinzua Viaduct" (PDF). Society for Industrial Archeology Newsletter. 34 (4): 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- "Emergency Repair Work Begins on Kinzua Bridge in McKean County" (Press release). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. February 27, 2003. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- "Twenty Must-See Pennsylvania State Parks". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved August 8, 2007. Note: Despite the title, there are twenty-one parks in the list, with Colton Point and Leonard Harrison State Parks treated as one.

- David de Vries (Director) (January 21, 2008). Life After People (Documentary). History Channel. ISBN 1-4229-0939-5.

- "Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 7/19/04 through 7/23/04". National Park Service. July 30, 2004. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- Lutz, Ted (October 10, 2008). "'Slim' chance is seen for tourist train". The Kane Republican.

- "Governor Rendell announces release of $700,000 for Kinzua Bridge State Park". Resource (newsletter). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. June 21, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- Lutz, Ted (September 16, 2011). "Ribbon cut to mark opening of Kinzua Sky Walk". The Kane Republican. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- "Visitors Invited to Walk Out and Observe Valley Below on Restored Portion of Viaduct at Kinzua Bridge State Park in McKean Count" (Press release). Pennsylvania Department of Conversation and Natural Resources. September 15, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

Sources

- Leech, Thomas G; McHaugh, Jonathan D; Dicarlantonio, George (November 2005). "Lessons from the Kinzua". Civil Engineering. American Society of Civil Engineers. 75 (11): 56–61. ISSN 0885-7024.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Packard, Vance (January 25, 1977). "Kinzua Viaduct" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved December 13, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kinzua Bridge. |

- Kinzua Railway Viaduct Historic Civil landmark at the American Society of Civil Engineers site

- "Collapse at Kinzua" (Open University)

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-7, "Erie Railway, Bradford Division, Bridge 27.66 (Kinzua Viaduct)"

- "Report on the July 21st Collapse of the Kinzua Viaduct". Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

| Preceding station | Erie Railroad | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riderville toward Carrollton |

Bradford Division | Mount Jewett toward Johnsonburg | ||