Kinzig (Rhine)

The Kinzig is a river in southwestern Germany, a right tributary of the Rhine.

| Kinzig | |

|---|---|

The Kinzig in Wolfach | |

.png) Course of the Kinzig | |

| Location | |

| Location | Baden-Württemberg |

| Reference no. | DE: 234 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Loßburg |

| • elevation | 682 m |

| Mouth | |

• location | In Kehl-Auenheim |

• elevation | 134 m |

| Length | 93.3 km (58.0 mi) [1] |

| Basin size | 1,403 km2 (542 sq mi) [1] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | at Schwaibach gauge [2] |

| • average | 22.8 m³/s |

| • minimum | Record low: 1.08 m³/s (in 14.09.1919) Average low: 3.62 m³/s |

| • maximum | Average high: 296 m³/s Record high: 914 m³/s (in 24.12.1919) |

| Basin features | |

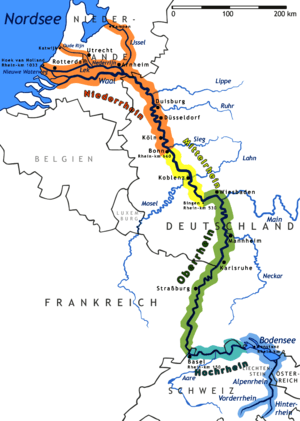

| Progression | Rhine→ North Sea |

| Landmarks |

|

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Aischbach, Rötenbach, Schiltach, Schiltersbach, Kirnbach, Gutach, Schutter |

| • right | Lohmühle, Kleine Kinzig, Heubach, Sulzbächle, Ippichen, Langenbach, Wolf, Harmersbach |

It runs for 93 km from the Black Forest through the Upper Rhine River Plains. The Kinzig valley and secondary valleys constitute the largest system of valleys in the Black Forest. Depending on the definition, the Kinzig is either the border between the Northern and Middle Black Forest or part of the Middle Black Forest. It is located entirely inside the State of Baden-Württemberg and its name is supposed to be of Celtic origin. During the last glacial period the Kinzig and the Murg created a common Kinzig-Murg river system.

Course of the river

The origin of the Kinzig is located on the land of the town of Loßburg in the district of Freudenstadt. It runs south, then makes a gradual turn to the west. It leaves the district of Freudenstadt just after it emerges from Alpirsbach, touches the district of Rottweil and continues to spend the largest part of its course in the district of Ortenau. The Kinzig leaves the Black Forest near Offenburg and flows into the Rhine near Kehl. The upper part the Kinzig is a true mountain river that over time has caused quite a few serious floods. Its middle and lower parts have been squeezed into a straight bed lined with tall levees. Renaturation is in progress in the area where the Schutter flows into the Kinzig.

Name

In 1099 the river was first mentioned in Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart as ad Chinzechun, ad aliam Chinzichun, in 1128 the Staatsarchive Sindelfingen referred to the river as Kinzicha. In 1539, 1543, 1560, 1620, 1652 and 1654 it was listed as Künzlin, Küntzgen, Kintzg, Kintzgen, Oberkentzgenwüß and Köntzig, respectively. In 1837 it was referred to for the first time as Kinzig.

According to Adolf Bach and Bruno Boesch there is some doubt about whether the name Kinzig can really be traced back to the ad Chinczechun, ad aliam Chinzichun of 1099. Bach points to the usage in the northern Breisgau where Kinzigs are described as "paths at the bottom of a canyon through the loess". In Upper Alsace and Graubünden rivers with the word Kinzig in their name usually describe a canyon. Some argue that the name developed from the Celtic kent meaning various kinds of quick movement or from the Lepontic word Centica (Cinti) which means "water".

With all these possibilities in mind, we can return to Adolf Bach and Bruno Boesch, who think these derivations doubtful. In addition, the question remains of how far the Celts or Pre-Celts had settled the Kinzig area, and which settlers had originally given the river its name. While these questions are difficult to answer for pre-historic times, the fact is that the Kinzig only created a small canyon in its upper part. A completely different river with many twists and turns presents itself as it moves towards the Upper Rhine River Plains. At the end of the last Ice Age it wound its way through the Plains for a long time, on the way absorbing the Murg and only joining the Rhine after it reached the general area of Hockenheim.

Tributaries

In the Black Forest many tributaries empty into the Kinzig, including several longer streams of 20-30 kilometres in length, most coming from the north or south. The following is a list of those over 10 kilometres in length:

- Little Kinzig, from the right near the Schenkenzell railway bridge, 20.2 km and 62.9 km².

- Schiltach, from the left in Schiltach, 29.5 km and 115.8 km².

- Wolf, formerly the Wolfach, from the right in Wolfach, 30.8 km and 129.6 km².

- Gutach, from the left near Gutach (Schwarzwaldbahn), 29.3 km and 161.5 km².

- Mühlbach or Welschensteinachbach, from the left near Steinach, 10.5 km and 24.9 km².

- Erlenbach, from the right near Biberach, 18.9 km (together with the rather larger Harmersbach, the much longer of its two headstreams, the Harmersbach and the Nordrach) and 102.9 km².

The largest tributary overall reaches the Kinzig a little before its mouth in the Upper Rhine Plain:

Importance as a transport and trade route

Timber rafting

In the past, the Kinzig was very important for timber rafting. The earliest mention of this trade on the Kinzig dates to the year 1339. The rafting towns of Wolfach and Schiltach had their own rafting corporations, which organized timber rafting to the Rhine and on to Holland; these corporations were the so-called Schifferschaften ("boatmen's associations"). They were given the sole rights of timber export by their respective overlords and ran a lucrative business that helped the towns' prosperity. Sebastian Münster writes in his Cosmographia universalis: "The people living by the River Kyntzig, especially around Wolfach, earn a living from the great quantity of construction timber, which the float down the waters of the Kyntzig to Strasburg and into the Rhine, and earn a great deal of money every year." Rafting on the Kinzig reached its peak in the 15th and 16th centuries and then again in the 18th century, when the demand for wood began to rise rapidly, as the Netherlands and England began to build their mighty naval and merchant fleets. The rafters could not match the capabilities of the newly introduced railways, however, and the last commercial timber raft ran down the Kinzig in 1896. Today, timber rafting festivals, museums in Gengenbach, Wolfach and Schiltach, as well as numerous technical facilities, such as weirs recall the timber rafting era.

Historical Roman road

The width, length and the favourable east-west direction of the middle and lower valley of the Kinzig make it important for as a communication route. For example, the Romans built a road that passed through the valley: the Kinzig Valley Way (Kinzigtalstrasse) is a Roman road which was built under the Emperor, Vespasian, in 73/74 A.D. from Offenburg through the valley to the simultaneously founded Roman town of Rottweil (Arae Flaviae) and on to Tuttlingen. It was mainly intended to create a shorter strategic link from Mainz to Augsburg, which had for a long time had to take a long detour via the Rhine Knee (Rheinknie) at Basle. During the revolt of the Batavi in 69/70 this detour had proved a problem.

Fauna and flora

Fauna

A regeneration program has been in progress since 2002 to re-introduce salmon into the Kinzig by putting young salmon into the water and removing obstacles. These efforts seem to be successful as in early 2005, for the first time in 50 years, salmon spawn were found in a river in Baden-Württemberg.

Flora

The Kinzig valley is the deepest in the inner Black Forest. In the lower Kinzig valley the villages are below 200 metres above sea level. The climate in the valley is therefore milder than in most other areas of the Black Forest. In the lower valley fruit and wine are produced; Gengenbach, Ortenberg and Ohlsbach are well-known names of wine-growing villages, some of which are on the Baden Wine Road. The countryside around the Kinzig valley in spring blooms far earlier than the surrounding regions of the Black Forest.

Infrastructure

The width, length and favourable east-west direction in the middle and lower valley make the Kinzig Valley important for infrastructure. The Romans maintained a road that traversed the valley. The Kinzigtalstraße was a military road built under Emperor Vespasian in 73/74 AD from Offenburg through the Kinzig Valley into the Roman Rottweil (Arae Flaviae) and on to Tuttlingen. The main purpose of the road was to shorten the strategically important connection between Mainz and Augsburg. Until this road was built, the connection took troops via the Rhine bend at Basel and during the revolt of the Batavers in 69/70 AD, this had proved to be a problem. During construction of the road, several Castelles were built. In addition to Rottweil, the rest areas in Offenburg-Rammersweier, Offenburg-Zunsweier, Waldmössingen, Sulz and Geislingen-Häsenbühl, were augmented by part of the Alb Limes fortifications in Frittlingen, Lautlingen and Burladingen-Hausen. All of them were located in Upper Germanic country except for Burladingen which was in Rhaetian territory. The surprising discovery of the fortification in Frittlingen in 1992 only a few kilometers southeast of Rottweil shows that the Kinzigtalstraße was secured and covered with a tight net of military fortifications. The suggestion that the Kinzig Valley itself was home to another fortification has thus gained credibility. Until then, it was supposed that there must have been one or two more yet to be discovered fortifications merely on the basis that the distance between the known ones in Offenburg and Waldmössingen was very big. Another fortification is assumed in Rottenburg by the end of the 1st century however, it is not clear whether it existed as early as 73/74 AD or not until later in 98 AD.

Roughly at the same time that the Kinzigtalstraße was built, Roman forts were constructed further north on the right side of the Rhine in places like Frankfurt, Heddernheim, Karben, Groß-Gerau, Gernsheim, Ladenburg (Lopodunum), Heidelberg and Baden-Baden (Aquae). Whether these were advanced posts or the Roman border between 73 and 98 AD, (following a generally defined line east of the Rhine), has yet to be determined.

In 98 AD, in the area of present-day southwest Germany, the route between Odenwald and Neckar came under Roman control, making the connection from Mainz to Augsburg shorter yet. As a result, the Kinzigtalstraße lost superregional significance.

In present-day Germany, the federal highway B 33 runs parallel to the Kinzig from Offenburg until it leaves the Kinzig in the upper valley to follow the Gutach towards Villingen-Schwenningen. From Hausach on towards Freudenstadt, the federal highway B 294, follows the upper Kinzig.

For the Black Forest Railway (Schwarzwaldbahn) train service, the valley is also very important. It runs from Offenburg to Hausach where it turns into the Gutach Valley to continue on to Konstanz at Lake Constance. In the upper Kinzig Valley, the Kinzig Valley Railway (Kinzigtalbahn) provides a connection between Hausach and Freudenstadt.

Towns and villages

(starting at the origin)

|

Castles, abbeys and stately homes

- Gallery

The Schenkenburg near Schenkenzell

The Schenkenburg near Schenkenzell Schloss Wolfach

Schloss Wolfach Abbey church and Loretto Chapel of the Capuchin abbey in Haslach, Feb 2006

Abbey church and Loretto Chapel of the Capuchin abbey in Haslach, Feb 2006 The ruins of Hohengeroldseck

The ruins of Hohengeroldseck- Gengenbach Abbey

Schloss Ortenberg, May 2008

Schloss Ortenberg, May 2008

- Alpirsbach Abbey, Alpirsbach

- Schenkenburg Castle, Schenkenzell

- Schiltach Castle, Schiltach

- Willenburg Castle, Schiltach

- Schloss Wolfach, Wolfach

- Husen Castle, Hausach

- Haslach Abbey, Haslach

- Hohengeroldseck Castle, between Seelbach and Biberach (Baden)

- Gengenbach Abbey, Gengenbach

- Schloss Ortenberg, Ortenberg (Baden)

References

Sources

- Emil Imm (ed.) - Land um Kinzig und Rench, Rombach-Verlag (1974)

- Kurt Klein - Leben am Fluss, Schwarzwald-Verlag (2002)

- STALF, A. (1932): Korrektion und Unterhaltung der Kinzig. Die Ortenau 19. pp 124–144.

- NEUWERCK, A. (1986): Der Lachsfang in der Kinzig. Die Ortenau 66. pp 499–525.

- Bach, Adolf, Deutsche Namenkunde, Bd. II/2, Heidelberg 1981

- Bahlow, Hans, Deutschlands geographische Namenwelt, Frankfurt 1985, p. 263

- Boesch, Bruno, Kleine Schriften zur Namenforschung, Heidelberg 1981

- Buck, M. R., Oberdeutsches Flurnamenbuch, Stuttgart 1880, p. 130

- Keinath, Walther, Orts- und Flurnamen in Württemberg, Stuttgart 1951

- Krahe, Hans, Unsere ältesten Flussnamen, Wiesbaden 1964

- Obermüller, Wilhelm, Deutsch – Keltisches Wörterbuch, 1872, Reprint-Druck, Vaduz 1993, Bd. II, pp 178f

- Springer, Otto, Die Flussnamen Württembergs und Badens, Stuttgart 1930, pp 53, 60

- Traub, Ludwig, Württembergische Flußnamen aus vorgeschichtlicher Zeit in ihrer Bedeutung für die einheimische Frühgeschichte, in: Württembergische Vierteljahrshefte für Landesgeschichte, XXXIV. Jahrgang, 1928, Stuttgart 1929, p. 16