Khoisan

Khoisan /ˈkɔɪsɑːn/, or according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography Khoe-Sān (pronounced: [kxʰoesaːn]), is a catch-all term for the "non-Bantu" indigenous peoples of Southern Africa, combining the Khoekhoen (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the Sān or Sākhoen (also, in Afrikaans: Boesmans, or in English: Bushmen,[3] after Dutch Boschjesmens; and Saake in the Nǁng language).

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~ 400,000[1] (c. 2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern Africa | |

| Languages | |

| Afrikaans,[2] Khoisan languages | |

| Religion | |

| Mainly Christian and African Traditional Religion (San religion) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pygmies |

Khoekhoen, specifically, were formerly known as "Hottentots",[4] which was an onomatopoeic term (from Dutch hot-en-tot) referring to the click consonants prevalent in the Khoekhoe languages, as they are in all the languages grouped under "Khoesān". Dutchmen in the early Cape settlement would ply Khoekhoen with liquor as an inducement for them to perform a ritual dance. The lyric accompanying the dance sounded, in Dutch ears, like "hot-en-tot".

Sān are popularly thought of as foragers in the Kalahari Desert and regions of Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho and South Africa. The word sān is from the Khoekhoe language and simply refers to foragers ("those who pick things up from the ground") who do not own livestock. As such it was used in reference to all hunter-gatherer populations of the Southern African region who Khoekhoe-speaking communities came into contact with, and was largely a term referring to a lifestyle, distinct from a pastoralist or agriculturalist one, not any particular ethnicity. While there are attendant cosmologies and languages associated with such a radical lifestyle, the term is an economic designator, rather than a cultural or ethnic one. However, Khoekhoen is considered to have ethnic meaning, as it refers to a number of historical populations of speakers of closely related languages that are considered to be the historical pastoralist communities in the South African Cape region, through to Namibia, where Khoekhoe populations of Nama and Damara people are prevalent ethnicities.

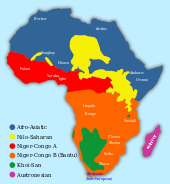

These Khoekhoe nations and Sān are grouped under the single term Khoesān as representing the indigenous substrate population of Southern Africa prior to the hypothesised Bantu expansion reaching the area, roughly between 1,500–2,000 years ago.

Many Khoesān peoples are the direct descendants of a very early dispersal of anatomically modern humans to Southern Africa, before 150,000 years ago. Their languages show a vague typological similarity, largely confined to the prevalence of click consonants, and they are not verifiably derived from a common proto-language, but are today split into at least three separate and unrelated language families (Khoe-Kwadi, ǃUi-Taa and Kxʼa). It has been suggested that the Khoekhoeǁaen (Khoekhoe peoples) may represent Late Stone Age arrivals to Southern Africa, possibly displaced by Bantu immigration.[5]

The compound term Khoisan / Khoesān is a modern anthropological convention, in use since the early-to-mid 20th century. Khoisan is a coinage by Leonhard Schulze in the 1920s and popularised by Isaac Schapera.[6] It enters wider usage from the 1960s, based on the proposal of a "Khoisan" language family by Joseph Greenberg.

Khoesān peoples were historically also grouped as Cape Blacks (Afrikaans: Kaap Swartes) or Western Cape Blacks (Afrikaans: Wes-Kaap Swartes) to distinguish them from the Niger-Congo-speaking "Bantoid" or "Congoid" blacks of the other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Derived from this is the term Capoid used in 20th century anthropological literature. An equivalent term derived from the compound Khoisan is Khoisanid, in use primarily in genetic genealogy.[7][8]

The term Khoisan (also spelled KhoiSan, Khoi-San, Khoe-San[9]) has also been introduced in South African usage as a self-designation after the end of apartheid, in the late 1990s. Since the 2010s, there has been a "Khoisan activist" movement demanding recognition and land rights from the Bantu majority.[10]

.jpg)

History

Origins

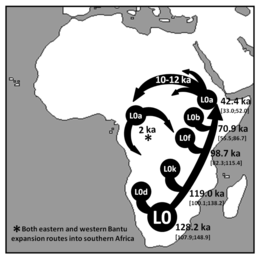

It is suggested that the ancestors of the modern Khoisan expanded to Southern Africa before 150,000 years ago, possibly as early as before 260,000 years ago,[12][13] so that by the beginning of the MIS 5 "megadrought", 130,000 years ago, there were two ancestral population clusters in Africa, bearers of mt-DNA haplogroup L0 in southern Africa, ancestral to the Khoi-San, and bearers of haplogroup L1-6 in central/eastern Africa, ancestral to everyone else.

Due to their early expansion and separation, the populations ancestral to the Khoisan have been estimated as having represented the "largest human population" during the majority of the anatomically modern human timeline, from their early separation before 150 ka until the recent peopling of Eurasia some 70 kya.[14] They were much more widespread than today, their modern distribution being due to their decimation in the course of the Bantu expansion. They were dispersed throughout much of Southern and South-Eastern Africa. There was also a significant back-migration of bearers of L0 towards eastern Africa between 120 and 75 kya. Rito et al. (2013) speculate that pressure from such back-migration may even have contributed to the dispersal of East African populations out of Africa at about 70 kya.[15] "By ~130 ka two distinct groups of anatomically modern humans co-existed in Africa: broadly, the ancestors of many modern-day Khoe and San populations in the south and a second central/eastern African group that includes the ancestors of most extant worldwide populations. Early modern human dispersals correlate with climate changes, particularly the tropical African "megadroughts" of MIS 5 (marine isotope stage 5, 135–75 ka) which paradoxically may have facilitated expansions in central and eastern Africa, ultimately triggering the dispersal out of Africa of people carrying haplogroup L3 ~60 ka. Two south to east migrations are discernible within haplogroup L0. One, between 120 and 75 ka, represents the first unambiguous long-range modern human dispersal detected by mtDNA and might have allowed the dispersal of several markers of modernity. A second one, within the last 20 ka signalled by L0d, may have been responsible for the spread of southern click-consonant languages to eastern Africa, contrary to the view that these eastern examples constitute relics of an ancient, much wider distribution."

Late Stone Age

The Khoisanid populations ancestral to the Khoisan were spread throughout much of Southern and Eastern Africa throughout the Late Stone Age, after about 75 ka. A further expansion, dated to about 20 ka, has been proposed based on the distribution of the L0d haplogroup. Rosti et al. suggest a connection of this recent expansion with the spread of click consonants to eastern African languages (Hadza language).[15]

The Late Stone Age Sangoan industry occupied southern Africa in areas where annual rainfall is less than a metre (1000 mm; 39.4 in).[16] The contemporary San and Khoi peoples resemble those represented by the ancient Sangoan skeletal remains.

Against the traditional interpretation that finds a common origin for the Khoi and San, other evidence has suggested that the ancestors of the Khoi peoples are relatively recent pre-Bantu agricultural immigrants to Southern Africa, who abandoned agriculture as the climate dried and either joined the San as hunter-gatherers or retained pastoralism.[17]

Bantuid expansion

Since the arrival of the Bantu expansion starting with the Sandawe people in Southern Africa over 1,500 years ago, linguistic influence is seen in the adoption of click consonants and loan words from Khoisan into the Xhosa and Zulu languages.[18] Bantu-speaking communities would have reached southern Africa from the Congo basin by about the 6th century AD.[19] The advancing Bantu encroached on the Khoikhoi territory, forcing survivors of the indigenous populations to move to more arid areas of the Kalahari.

Their husbandry of sheep, goats and cattle grazing in fertile valleys across the region provided a stable, balanced diet, and allowed the Khoikhoi to live in larger groups in a region previously occupied by the San, who were subsistence hunter-gatherers. Advancing Bantu in the 3rd-6th century AD encroached on the Khoikhoi territory, pushing them into more arid areas.The Bantu people, with advanced agriculture and metalworking technology, outcompeted and intermarried with the Khoisan, becoming the dominant population of South-Eastern Africa before the arrival of the Dutch colonists in 1652.[20]

After the arrival of the Bantu, the Khoisan and their pastoral or hunter-gatherer ways of life remained predominant west of the Fish River in South Africa and in deserts throughout their region, where the drier climate precluded the growth of Bantu crops suited for warmer and wetter climates.[21]

Historical period

The Khoikhoi enter the historical record with their first contact with Portuguese explorers, about 1,000 years after their displacement by the Bantu. Local population dropped after the Khoi were exposed to smallpox from Europeans. The Khoi waged more frequent attacks against Europeans when the Dutch East India Company enclosed traditional grazing land for farms. Khoikhoi social organisation was profoundly damaged and, in the end, destroyed by colonial expansion and land seizure from the late 17th century onwards. As social structures broke down, some Khoikhoi people settled on farms and became bondsmen (bondservants) or farm workers; others were incorporated into existing clan and family groups of the Xhosa people. Georg Schmidt, a Moravian Brother from Herrnhut, Saxony, now Germany, founded Genadendal in 1738, which was the first mission station in southern Africa,[22] among the Khoi people in Baviaanskloof in the Riviersonderend Mountains. Early European settlers sometimes intermarried with Khoikhoi women, resulting in a sizeable mixed-race population now known as the Griqua.

Andries Stockenström facilitated the creation of the "Kat River" Khoi settlement near the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony. The settlements thrived and expanded, and Kat River quickly became a large and successful region of the Cape that subsisted more or less autonomously. The people were predominantly Afrikaans-speaking Gonaqua Khoi, but the settlement also began to attract other Khoi, Xhosa and mixed-race groups of the Cape.

The so-called "Bushman wars"were to a large extent the response of the San after their dispossession.

At the start of the 18th century, the Khoikhoi in the Western Cape lived in a co-operative state with the Dutch. By the end of the century the majority of the Khoisan operated as 'wage labourers', not that dissimilar to slaves. Geographically, the further away the labourer was from Cape Town, the more difficult it became to transport agricultural produce to the markets. The issuing of grazing licences north of the Berg River in what was then the Tulbagh Basin propelled colonial expansion in the area. This system of land relocation led to the Khoijhou losing their land and livestock as well as dramatic change in the social, economic and political development.[23]

After the defeat of the Xhosa rebellion in 1853, the new Cape Government endeavoured to grant the Khoi political rights to avert future racial discontent. The government enacted the Cape franchise in 1853, which decreed that all male citizens meeting a low property test, regardless of colour, had the right to vote and to seek election in Parliament. This non-racial principle was later abolished by the apartheid Government.[24]

In the Herero and Namaqua genocide in German South-West Africa, over 10,000 Nama are estimated to have been killed during 1904–1907.[25][26]

The San of the Kalahari were described in Specimens of Bushman Folklore by Wilhelm H. I. Bleek and Lucy C. Lloyd (1911). They were brought to the globalised world's attention in the 1950s by South African author Laurens van der Post in a six-part television documentary. The Ancestral land conflict in Botswana concerns the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), established in 1961 for wildlife, while the San were permitted to continue their hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In the 1990s, the government of Botswana began a policy of "relocating" CKGR residents outside the reserve. In 2002, the government cut off all services to CKGR residents. A legal battle began, and in 2006 the High Court of Botswana ruled that the residents had been forcibly and unconstitutionally removed. The policy of relocation continued, however, and in 2012 the San people (Basarwa) appealed to the United Nations to force the government to recognise their land and resource rights.

Following the end of Apartheid in 1994, the term "Khoisan" has gradually come to be used as a self-designation by South African Khoikhoi as representing the "first nations" of South Africa vis-a-vis the ruling Bantu majority. A conference on "Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage" was organised by the University of the Western Cape in 1997.[27] and "Khoisan activism" has been reported in the South African media beginning in 2015.[10]

The South African government allowed Khoisan families (up until 1998) to pursue land claims which existed prior to 1913. The South African Deputy Chief Land Claims Commissioner, Thami Mdontswa, has said that constitutional reform would be required to enable Khoisan people to pursue further claims to land from which their direct ancestors were removed prior to 9 June 1913.[28]

"Bosjemans frying locusts", aquatint by Samuel Daniell (1805).

"Bosjemans frying locusts", aquatint by Samuel Daniell (1805). San woman in Namibia (1984 photograph)

San woman in Namibia (1984 photograph)

Languages

The "Khoisan languages" were proposed as a linguistic phylum by Joseph Greenberg in 1955.[29] Their genetic relationship was questioned later in the 20th century, and the term now serves mostly as a convenience term without implying genetic unity, much like "Papuan" and "Australian" are.[30] Their most notable uniting feature is their click consonants.

They are categorized in two families, and a number of possible language isolates.

The Kxʼa family was proposed in 2010, combining the ǂʼAmkoe (ǂHoan) language with the ǃKung (Juu) dialect cluster. ǃKung includes about a dozen dialects, with no clear-cut delineation between them. Sands et al. (2010) propose a division into four clusters:

- Northern ǃKung (Sekele), spoken in Angola around the Cunene, Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando rivers (but with many refugees now in Namibia),

- North-Central ǃKung (Ekoka), spoken in Namibia between the Ovambo River and the Angolan border,

- Central ǃKung, spoken around Grootfontein, Namibia, west of the central Omatako River and south of the Ovambo River

- Southeastern ǃKung (Juǀ'hoan), spoken in Botswana east of the Okavango Delta, and northeast Namibia from near Windhoek to Rundu, Gobabis, and the Caprivi Strip.[31]

The Khoi (Khoe) family is divided into a Khoikhoi (Khoekhoe and Khoemana dialects) and a Kalahari (Tshu–Khwe) branch. The Kalahari branch of Khoe includes Shua and Tsoa (with dialects), and Kxoe, Naro, Gǁana and ǂHaba (with dialects). Khoe also has been tentatively aligned with Kwadi ("Kwadi–Khoe"), and more speculatively with the Sandawe language of Tanzania ("Khoe–Sandawe"). The Hadza language of Tanzania has been associated with the Khoisan group due to the presence of click consonants.

Physical characteristics and genetics

Charles Darwin wrote about the Khoisan and sexual selection in The Descent of Man in 1882, commenting that their steatopygia evolved through sexual selection in human evolution, and that "the posterior part of the body projects in a most wonderful manner".[32]

In the 1990s, genomic studies of the world's peoples found that the Y chromosome of San men share certain patterns of polymorphisms that are distinct from those of all other populations.[33] Because the Y chromosome is highly conserved between generations, this type of DNA test is used to determine when different subgroups separated from one another, and hence their last common ancestry. The authors of these studies suggested that the San may have been one of the first populations to differentiate from the most recent common paternal ancestor of all extant humans.[34][35]

Various Y-chromosome studies[36][37][38] since confirmed that the Khoisan carry some of the most divergent (oldest) Y-chromosome haplogroups. These haplogroups are specific sub-groups of haplogroups A and B, the two earliest branches on the human Y-chromosome tree.

Similar to findings from Y-Chromosome studies, mitochondrial DNA studies also showed evidence that the Khoisan people carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. The most divergent (oldest) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African Khoi and San groups.[36][39][40][41] The distinctiveness of the Khoisan in both matrilineal and patrilineal groupings is a further indicator that they represent a population historically distinct from other Africans.[42]

See also

- Peopling of Africa

- San religion

References

- Their total numbers are estimated at roughly 300,000 Khoikhoi and 90,000 San: 200k Nama people (2010): Brenzinger, Matthias (2011) "The twelve modern Khoisan languages." In Witzlack-Makarevich & Ernszt (eds.), Khoisan languages and linguistics: proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium, Riezlern / Kleinwalsertal (Research in Khoisan Studies 29). 100k Damara people (1996): James Stuart Olson, « Damara » in The Peoples of Africa: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, p. 137. 50-60k San people in Botswana (2010): Anaya, James (2 June 2010). Addendum – The situation of indigenous peoples in Botswana (PDF) (Report). United Nations Human Rights Council. A/HRC/15/37/Add.2..

- Parkinson, Christian (2016-06-14). "The first South Africans fight for their rights". BBC News.

Most [Khoisan people] now speak Afrikaans as their first language.

- University of Utah anthropologist Henry Harpending, who has lived with the famous tongue-clicking hunter-gatherers said, "In the 1970s the name San spread in Europe and America because it seemed to be politically correct, while Bushmen sounded derogatory and sexist. Unfortunately, the hunter-gatherers never actually had a collective name for themselves in any of their own languages. San was actually the insulting word that the herding Khoi people called the Bushmen. [...] one did not call someone a San to his face. I continued to use Bushman, and I was publicly corrected several times by the righteous. [...] Sailer, Steve (20 June 2002). "Name game – 'Inuit' or 'Eskimo'?". Feature. UPI. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Hottentot, n. and adj. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Barnard, Alan (1992). Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A comparative ethnography of the Khoisan peoples. New York, NY; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Schapera, Isaac (1930). The Khoisan peoples of South Africa: Bushmen and Hottentots. Routledge.

- The word "Khoisanid" enters occasional usage already in the 1930s based on Schapera's "Khoisan" (1930), e.g. United States Armed Forces Institute Education Manual. 1938. p. 114..

- The use of "Khoisanid" in genetics and genealogy was introduced by Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; et al. (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes..

- The hyphenated spelling Khoe-San or Khoi-San is recent (post-1990). Note that this usage is distinct from the occasional usage of Khoi-San for the Khoe-speaking subset of the San, e.g. "the Ai-San, the Kun-San, the Au-ai-san, the An-San, the Matsana-Khoi-San, and the Bushmen of Otave" in John Noble, Illustrated Official Handbook of the Cape and South Africa (1893), p. 395. Spellings Khoi-San and Khoe-San in Mohamed Adhikar, Burdened by Race: Coloured Identities in Southern Africa (2009), p. 148.

- Khoisan march to Parliament to demand land rights, ENCA, 3 December 2015. Pelane Phakgadi, Ramaphosa meets aggrieved Khoisan activists at Union Buildings, Eyewitness News, 24 December 2017. Illegitimate Khoisan leaders are trying to exploit new bill, IOL, 17 April 2018.

- Behar, Doron M.; Villems, Richard; Soodyall, Himla; Blue-Smith, Jason; Pereira, Luisa; Metspalu, Ene; Scozzari, Rosaria; Makkan, Heeran; Tzur, Shay; Comas, David; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Wells, R. Spencer; Rosset, Saharon (May 2008). "The Dawn of Human Matrilineal Diversity". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (5): 1130–1140. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.002. PMC 2427203. PMID 18439549.

Both the tree phylogeny and coalescence calculations suggest that Khoisan matrilineal ancestry diverged from the rest of the human mtDNA pool 90,000–150,000 years before present (ybp)

- Schlebusch, Carina M.; Malmström, Helena; Günther, Torsten; Sjödin, Per; Coutinho, Alexandra; Edlund, Hanna; Munters, Arielle R.; Vicente, Mário; Steyn, Maryna; Soodyall, Himla; Lombard, Marlize; Jakobsson, Mattias (3 November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

- Estimated split times given in the source cited (in kya): Human-Neanderthal: 530-690, Deep Human [H. sapiens]: 250-360, NKSP-SKSP: 150-190, Out of Africa (OOA): 70-120.

- Kim, Hie Lim; Ratan, Aakrosh; Perry, George H.; Montenegro, Alvaro; Miller, Webb; Schuster, Stephan C. (4 December 2014). "Khoisan hunter-gatherers have been the largest population throughout most of modern-human demographic history". Nature Communications. Nature Publishing Group. 5: 5692. doi:10.1038/ncomms6692. PMC 4268704. PMID 25471224.. Science, December 4, 2014

- Rito, Teresa; Richards, Martin B.; Fernandes, Verónica; Alshamali, Farida; Cerny, Viktor; Pereira, Luísa; Soares, Pedro; Gilbert, Tom (13 November 2013). "The First Modern Human Dispersals across Africa". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80031. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080031. PMC 3827445. PMID 24236171.

- Lee, Richard B. (1976), Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers: Studies of the ǃKung San and Their Neighbors, Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore, eds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- Güldemann, Tom (2020-02-27), "Changing Profile When Encroaching on Forager Territory", The Language of Hunter-Gatherers, Cambridge University Press, pp. 114–146, ISBN 978-1-139-02620-8, retrieved 2020-05-27

- Brigitte Pakendorf, Koen Bostoen, Bonny Sands and Hilde Gunnink (2017)Prehistoric Bantu-Khoisan language contact, Language Dynamics and Change ,7(1), DOI: 10.1163/22105832-00701002

- Phillipson, D. W. (April 1977). "The Spread of the Bantu Language". Scientific American. 236 (4): 106–114. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0477-106. ISSN 0036-8733.

- Diamond, 394–7.

- Pikirayi, Innocent (2014), "Southern Africa: Historical Archaeology", Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, Springer New York, pp. 6883–6887, ISBN 978-1-4419-0426-3, retrieved 2020-05-27

- The Pear Tree Blossoms, Bernhard Krueger, Hamburg, Germany

- Wilmot Godfrey James, Mary Simons. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey.Class, Caste, and Color: A Social and Economic History of the South African Western Cape. pp. 1–10.

- Fraser, Ashleigh (3 June 2013). "A Long Walk To Universal Franchise in South Africa". HSF.org.za. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes (2008) Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904–1908, p. 142, Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-313-36256-9

- Moses, A. Dirk (2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation and Subaltern Resistance in World History. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781845454524.

- Hitchcock, Robert K.; Biesele, Megan. "San, Khwe, Basarwa, or Bushmen? Terminology, Identity, and Empowerment in Southern Africa". Kalahari Peoples Fund. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Mercedes Besent. "SABC News - Possible constitution changes for Khoisan land claims: Wednesday 16 October 2013". sabc.co.za. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1955. "Studies in African Linguistic Classification" New Haven: Compass Publishing Company. (Reprints, with minor corrections, a series of eight articles published in the "Southwestern Journal of Anthropology" from 1949 to 1954.)

- Bonny Sands (1998). Eastern and Southern African Khoisan: Evaluating Claims of Distant Linguistic Relationships. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, Cologne.

- Sands, Bonny (2010). Brenzinger, Matthias; König, Christa, eds. "Juu Subgroups Based on Phonological Patterns". Khoisian Language and Linguistics: the Riezlern Symposium 2003. Cologne, Germany: Rüdiger Köppe: 85–114.

- Charles Darwin (1882). The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: John Murray. p. 578.

- "Dwindling African tribe may have been most populous group on planet". sciencemag.org.

- Schuster, SC; et al. (2010). "Complete Khoisan and Bantu genomes from Southern Africa". Nature. 463 (7283): 943–947. doi:10.1038/nature08795. PMC 3890430. PMID 20164927.

- Mayell, Hillary (December 2002). "Documentary Redraws Humans' Family Tree". National Geographic.

- Knight, Alec; Underhill, Peter A.; Mortensen, Holly M.; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Lin, Alice A.; Henn, Brenna M.; Louis, Dorothy; Ruhlen, Merritt; Mountain, Joanna L. (2003). "African Y chromosome and mtDNA divergence provides insight into the history of click languages". Current Biology. 13 (6): 464–73. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00130-1. PMID 12646128.

- Hammer MF, Karafet TM, Redd AJ, Jarjanazi H, Santachiara-Benerecetti S, Soodyall H, Zegura SL (2001). "Hierarchical patterns of global human Y-chromosome diversity" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (7): 1189–203. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003906. PMID 11420360.

- Naidoo T, Schlebusch CM, Makkan H, Patel P, Mahabeer R, Erasmus JC, Soodyall H (2010). "Development of a single base extension method to resolve Y chromosome haplogroups in sub-Saharan African populations". Investigative Genetics. 1 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-1-6. PMC 2988483. PMID 21092339.

- Chen YS, Olckers A, Schurr TG, Kogelnik AM, Huoponen K, Wallace DC (2000). "mtDNA variation in the South African Kung and Khwe, and their genetic relationships to other African populations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (4): 1362–83. doi:10.1086/302848. PMC 1288201. PMID 10739760.

- Tishkoff, SA; Gonder, MK; Henn, BM; Mortensen, H; Knight, A; Gignoux, C; Fernandopulle, N; Lema, G; et al. (2007). "History of click-speaking populations of Africa inferred from mtDNA and Y chromosome genetic variation" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (10): 2180–95. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm155. PMID 17656633.

- Schlebusch CM, Naidoo T, Soodyall H (2009). "SNaPshot minisequencing to resolve mitochondrial macro-haplogroups found in Africa". Electrophoresis. 30 (21): 3657–64. doi:10.1002/elps.200900197. PMID 19810027.

- Pickrell, Joseph K.; Patterson, Nick; Loh, Po-Ru; Lipson, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Stoneking, Mark; Pakendorf, Brigitte; Reich, David (2014-02-18). "Ancient west Eurasian ancestry in southern and eastern Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (7): 2632–2637. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313787111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3932865. PMID 24550290.

Bibliography

- Barnard, Alan (2004) Mutual Aid and the Foraging Mode of Thought: Re-reading Kropotkin on the Khoisan. Social Evolution & History 3/1: 3–21.

- Coon, Carleton: The Living Races of Man (1965)

- Diamond, Jared (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31755-8..

- Hogan, C. Michael (2008) "Makgadikgadi" at Burnham, A. (editor) The Megalithic Portal

- Lee, Richard B. (1979), The ǃKung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, Andrew; Malherbe, Candy; Guenther, Mat and Berens, Penny (2000), Bushmen of Southern Africa: Foraging Society in Transition. Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1341-4

- Thomas, Elizabeth Marshall (1958, 1989) The Harmless People.

- Thomas, Elizabeth Marshall (2006). The Old Way: A Story of the First People.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khoisan. |

- The Khoisan-speaking Peoples

- The Khoisan

- Home of the Southern African San

- "Khoesan languages" from Web Resources for African Languages

- Africa's Khoe-San were first to split from other humans

- Khoisan people represent 'earliest' branch off human family tree, By Ian Steadman, 24 September 2012.