Harpoot

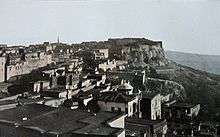

Harput (also called Karput, Kharput, or Kharpert; Armenian: Խարբերդ) is an ancient town in Turkey, in the Ottoman Empire, falling under Mamuret-ul-Aziz Vilayet by the end of the empire; its site is now in the Elazığ Province. Artifacts belonging to around 2,000 BC were found in the area. The town is famous for its Harput Castle, and incorporates a museum, old mosques, a church, and the Buzluk (Ice) Cave.

Harput was a largely Armenian populated region in Western Armenia in medieval times.[1] The ancient Kingdom of Sophene and later the Armenian province of Sophene laid in medieval Kharput.[2] Harput is about 700 miles (1,100 km) from Istanbul.[3]

Background

The name Kharput is of Armenian origin, it comes from the Armenian Kharberd or Karberd which contains the word "berd" meaning castle.[4]

Harput was an ancient Urartu fortress town which Armenians established as their capital city in the 10th century, until taken by the Ottomans in 1515.[5]

Harput was developed as a military base during the second Byzantine occupation of the region, after 938. An imposing fortress was built on a wide rock outcropping overlooking the valley from the south. A town grew around the fortress, with a primarily Syrian and Armenian population that came from nearby villages as well as the city of Arsamosata further east. By the late 11th century, Harput had eclipsed Arsamosata to become the main settlement in the region. Around 1085, a Turkish warlord named Çubuk conquered Harput and was confirmed as its ruler by the Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah I. The Great Mosque of Harput was built opposite the citadel by either Çubuk or his son (attested as the ruler here in 1107).[6]

The first Artukid ruler of Harput was Balak, who was related to the Artukid rulers of Mardin and Hisn Kayfa but not directly part of either ruling family. Balak died young in 1124 and the Artukids of Hisn Kayfa took over. Later, Imad ad-Din Abu Bakr, an Artukid prince who had previously attempted to usurp the throne of Hisn Kayfa, gained control of Harput. Harput remained an independent Artukid principality until 1234, when it was conquered by the Seljuks. It was during the Artukid period that the former population of Arsamosata became fully absorbed by Harput. In the early 1200s, one of the Artukid princes may have entirely rebuilt the citadel. In the subsequent period of Seljuk rule, not much was built in Harput.[6]

From the mid-14th century until 1433, Harput became part of the Beylik of Dulkadir. It was one of the main cities in the beylik, and the citadel was again rebuilt during this period. The Aq Qoyunlu ruled Harput from 1433-1478; the Aq Qoyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan's wife, a Greek Christian from Trebizond, lived here with her Greek entourage. Ottoman rule began in Harput in 1515. Under the Ottomans, Harput remained a prosperous industrial center, with thriving silk-weaving and carpet-making industries and many medreses. In the 19th century, an American missionary school was established near the citadel, providing an education mainly for Armenians. There was also a French missionary school.[6]

In 1834, however, the governors of the Sanjak of Harput moved their residence to the town of Mezre, on the plain to the northeast, and some of Harput's population moved with them. In 1838 a barracks was built in Mezre as a local base against Muhammad Ali of Egypt. In 1879, Mezre was built up into a large city named Mamuret el-Aziz, which became modern Elaziğ.[6]

Rev. Dr. Herman N. Barnum account of Harput in the 1800s,

The city of Harput has a population of perhaps 20,000, and it is located a few miles east of the river Euphrates, near latitude thirty-nine, and east from Greenwich about thirty-nine degrees. It is on a mountain facing south, with a populous plain 1,200 feet below it. The Taurus Mountains lie beyond the plain, twelve miles [19 km] away. The Anti-Taurus range lies some forty miles [64 km] to the north in full view from the ridge just back of the city. The surrounding population are mostly farmers, and they all live in villages. No city in Turkey is the center of so many Armenian villages, and the most of them are large. Nearly thirty can be counted from different parts of the city. This makes Harput a most favorable missionary center. Fifteen out-stations lie within ten miles [16 km] of the city. The Arabkir field, on the west, was joined to Harput in 1865, and the following year…the larger part of the Diarbekir field on the south; so that now the limits of the Harput station embrace a district nearly one third as large as new England.[7]

Harput was affected by the Hamidian massacres in the 1890s.[8]

Circa 1910 the travel time from Constantinople (now Istanbul) to Harput was about three days by train and then 18 days on horseback.[3]

American consulate

The United States consulate started from January 1, 1901 with Dr. Thomas H. Norton as the consul;[9] he had no previous experience in international relations, as the U.S. was just recently establishing its diplomatic network.[10] The consulate was established to assist missionaries. The Ottoman Ministry of Internal Security gave him a tezkere travel permit, but the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs initially refused to recognize the consulate.[9]

The building had three stories, a wall, and a garden with mulberry trees.[3]

Leslie A. Davis became consul of Harput in 1914 and left in 1917 upon the cessation of Ottoman Empire-United States relations; Davis stated that this mission was "one of the most remote and inaccessible in the world".[3]

In fiction

It’s the scene of the romance “Skylark Farm” by Antonia Arslan about Armenian Genocide and it is also her own grandfather's birthplace.[11]

Armenian Genocide

Two eyewitnesses wrote about reports of genocide in Harput. One of them being Dr. Henry H. Riggs, the congregational minister and ABCFM missionary who had been the head of Euphrates College, a local college founded and directed by American missionaries for mostly the Armenian community in the region. His report was documented and sent over to the United States, and then published under Days of Tragedy in Armenia, 1997.[12] The second eyewitness was Davis.[12] Davis hid about 80 Armenians in the consulate grounds.[3]

See also

References

- Selcuk Esenbel; Bilge Nur Criss; Tony Greenwood. American Turkish Encounters: Politics and Culture, 1830-1989. p. 78.

- Lacey, James (109). Great Strategic Rivalries: From the Classical World to the Cold War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9789004350724.}

- White, Edward (2017-02-03). "The Great Crime". The Paris Review. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- M. Th. Houtsma. E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 4. p. 915.

- Day, David. Conquest: How Societies Overwhelm Others.

- Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. pp. 18–34. ISBN 0907132340. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Rev.Herman Norton Barnum. The Missionary Herald vol. 88. pp. 144–147.

- Mayersen, Deborah. "The 1895-1896 Armenian Massacres in Harput: Eyewitness Account". Études Arméniennes Contemporaines. pp. 161–183. doi:10.4000/eac.1641.

- Armenian Perspectives: 10th Anniversary Conference of the Association Internationale Des Études Arméniennes, School of Oriental and African Studies, London. Psychology Press, 1997. ISBN 0700706100, 9780700706105. p. 293.

- Armenian Perspectives: 10th Anniversary Conference of the Association Internationale Des Études Arméniennes, School of Oriental and African Studies, London. Psychology Press, 1997. ISBN 0700706100, 9780700706105. p. 2937.

- "ARSLAN, Yerwant in "Dizionario Biografico"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- Merrill D. Peterson. "Starving Armenians": America and the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1930 and After. p. 35.