Kenneth Whiting

Kenneth Whiting (22 July 1881 – 24 April 1943) was a United States Navy officer who was a pioneer in submarines and is best known for his lengthy career as a pioneering naval aviator. During World War I, he commanded the first American military force to arrive in Europe for combat. After the war, he was instrumental in development of the aircraft carrier in the United States, where he sometimes is known as the U.S. Navy's "father of the aircraft carrier." He was involved in some way in the design or construction of five of the first six U.S. Navy aircraft carriers, and served as acting commanding officer of the first carrier to enter U.S. Navy service and as executive officer of the first two American carriers. In the earliest days of the U.S. Navy's development of an aircraft carrier force, he led many shipboard innovations still in use aboard carriers today.

Kenneth Whiting | |

|---|---|

Commander Kenneth Whiting aboard the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) during his 1927–1929 tour as her executive officer. | |

| Born | 22 July 1881 Stockbridge, Massachusetts |

| Died | 24 April 1943 (aged 61) Bethesda, Maryland |

| Buried | sea off Execution Rocks in Long Island Sound |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1905–1943 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

Birth and early career

Whiting was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, on 22 July 1881, but moved to Larchmont, New York, at an early age. Larchmont remained his residence for the rest of his life.[4] He was appointed as a naval cadet on 7 September 1900 and became a midshipman from New York at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1901. After graduating from the Naval Academy on 30 January 1905,[5] he reported aboard the armored cruiser USS West Virginia. After serving the requisite sea duty, he was commissioned as an ensign on either 31 January 1907[6] or 25 February 1908, according to different sources.[7]

In June 1907, Whiting detached from West Virginia and transferred to the gunboat USS Concord in the United States Asiatic Fleet. He transferred again, to the steamer USS Supply, in May 1908.[8]

Submarine service

After a brief stint aboard Concord again from August to October 1908,[9] Whiting volunteered for submarine duty[10] and was reassigned to command of the submarine USS Shark at Naval Station Cavite in the Philippine Islands to oversee her fitting-out. He then assumed command of the submarine USS Porpoise at Cavite on 20 November 1908.[11]

On 15 April 1909, Whiting took Porpoise out for what his crew of six thought would be a routine run. After Porpoise leveled off in Manila Bay at a depth of 20 feet (6.1 meters), Whiting informed his crew that he was convinced that a man could escape from a submarine through a torpedo tube and that he intended to test the idea on himself. He squeezed into Porpoise's 18-inch (460-mm) tube and clung to the crossbar which stiffened the outer torpedo tube door as the crew closed the inner door. When the crew opened the outer door and seawater rushed in, Whiting hung onto the crossbar, which drew his elbows out of the tube's mouth, and then muscled his way out using his hands and arms. After 77 seconds, he was free of the submarine and swam to the surface; Porpoise soon surfaced and recovered him. Reluctant to speak about the incident in public – in Porpoise's log that day, Whiting simply commented, "Whiting went through the torpedo tube, boat lying in water in normal condition, as an experiment..." – he nevertheless informed his flotilla commander, Lieutenant Guy W. S. Castle, who submitted a report on how the feat had been accomplished.[12]

In September 1910, Whiting detached from Porpoise. He next took command of the Atlantic Fleet submarine USS Tarpon. In January 1911, he reported to the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Newport News, Virginia, to fit out the new submarine USS Seal, which was renamed G-1 later that year. He became the first commanding officer of G-1 when she was commissioned on 28 October 1912.[13]

Naval aviation

In 1910, Whiting applied for flight training by Glenn Curtiss and talked his friend from the submarine service Theodore G. Ellyson into applying as well. Ellyson was accepted and went on to become Naval Aviator No. 1 in 1911, but Whiting was not and continued his submarine duties.[14] On 29 June 1914, however, Whiting finally began his career in naval aviation, the field in which he was to make his name as a true pioneer, when he reported to the Wright Company at Dayton, Ohio, to learn to fly.[15] The last naval officer to take flight training from Orville Wright personally,[16] Whiting was designated Naval Aviator No. 16 on 6 September 1914.[17]

Whiting then became officer-in-charge of the Naval Aeronautic Station at Pensacola, Florida. He and fellow naval aviator Henry C. Mustin worked together on seaplane designs and filed a patent application for the design of a "hydroaeroplane" on 27 October 1916.[18] In November 1916, he transferred to the armored cruiser USS Washington – renamed USS Seattle on 1 December 1916 – and took command of a unit of seaplanes attached to the ship.[19]

Whiting would later become a member of the Early Birds of Aviation, an organization founded in 1928 and dedicated to the history of pilots who learned to fly before 17 December 1916.

World War I

The United States entered World War I on 6 April 1917, and Whiting was selected to command the 1st Naval Air Unit (or First Aeronautic Detachment) and assigned to the collier USS Neptune in May 1917. The unit's seven officers and 122 enlisted men crossed the Atlantic Ocean to France aboard Neptune and the collier USS Jupiter to become the first American military unit to debark in Europe for combat, with Jupiter arriving at Pauillac on 5 June 1917 and Neptune at St. Nazaire on 8 June 1917.[20][21][22]

With only vague guidance and, at first, no aircraft, Whiting set about establishing a European presence for U.S. Navy aviation.[23] In June 1917, he selected Dunkirk as the site for a U.S. Navy air base,[24] laying the groundwork for the establishment in 1918 of the U.S. Navy's Northern Bombing Group.[25] He also instructed French pilots.

On 1 June or 20 July 1918, according to different sources, Whiting, by now promoted to lieutenant commander, took command of Naval Air Stations 14 and 15 at RNAS Killingholme, England.[26][27]

For his World War I service, Whiting was awarded the Navy Cross "for exceptionally meritorious service in a duty of great responsibility,"[28] and France awarded him the Legion of Honor (Chevalier).[29]

Interwar aircraft carrier advocacy

Whiting sometimes is referred to as the U.S. Navy's "father of the aircraft carrier." He had begun agitating for U.S. Navy development of what were then called "plane carriers" in the spring of 1916,[30] and as early as March 1917 he had proposed to United States Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels that the Navy acquire a ship with an aircraft catapult and a flight deck, prompting the first serious U.S. Navy consideration of the acquisition of any kind of aviation ship since the American Civil War of 1861–1865.[31] The United States Department of the Navy rejected his proposal on 20 June 1917.[32] In the years between World War I and World War II, however, Whiting would be instrumental in the construction of five of the U.S. Navy's first six aircraft carriers and serve as executive officer of its first two.[33] He also served as acting commanding officer of its first carrier at a time when the United States was experimenting with many aspects of the operation of aircraft carriers and their aircraft.

Returning to the United States after World War I, Whiting was assigned to the Chief of Naval Operations' Office of Naval Aviation in Washington, D.C., in 1919.[34] Testifying along with other leading naval aviators, including Henry C. Mustin and John Henry Towers, before the General Board of the United States Navy about the need for U.S. Navy aircraft carriers, Whiting was partially responsible for the General Board's April 1919 recommendation that the collier USS Jupiter be converted into the U.S. Navy's first aircraft carrier. On 11 July 1919, the United States Congress authorized Jupiter's conversion into the carrier, which later would be named USS Langley (CV-1).[35][36][37]

Later in 1919, after the battleship USS Texas (BB-35) experimented successfully with the use of aircraft to spot her gunfire and found that the aircraft spotters allowed her greater accuracy, Whiting testified before the General Board, attesting that aircraft spotting could increase the accuracy of ship gunnery by up to 200 percent.[38] The success of the experiments led the Navy to embark floatplanes aboard all of its battleships and cruisers.[39]

On 1 September 1921 Whiting transferred to the Navy's newly established Bureau of Aeronautics.[40] There he continued his advocacy for an American aircraft carrier force. In January 1922, he said, "The Langley when commissioned will provide our Navy with an experimental ' carrier' which, while not ideal, will be sufficiently serviceable to conduct any experiment required for the design of future 'carriers' and for the development of naval aerial tactics, and for the development of the various types of aircraft...for these last are also lacking in our Navy, due to concentrating on anti-submarine work during the War [i.e., World War I]. That 'carriers' will be successful, and an absolute necessity to any well-equipped navy in the future, there is not the slightest doubt in my mind. We are asking this Congress for the first properly designed 'carrier.' It will take from three to four years to build it. Will they give it to us?"[41] The "properly designed" carriers Whiting wanted first began to appear in 1927, with the commissioning of USS Saratoga (CV-3) and USS Lexington (CV-2).

USS Langley (CV-1)

Whiting reported aboard Langley on 20 March 1922, the day of her commissioning, as her first executive officer, also serving on an acting basis as her first commanding officer and thus becoming the first person to command a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier.[42] Langley was far too slow to keep up with the battle fleet,[43] and her main purpose was to serve as a laboratory for the exploration of the new naval warfare discipline of aircraft carrier operations, with her personnel and those of her embarked air squadrons experimenting to discover what practices worked best.[44] Flying a Vought VE-7, Lieutenant Virgil C. Griffin made the first takeoff from an American carrier from Langley on 17 October 1922, and Lieutenant Commander Godfrey Chevalier made the first landing on 26 October 1922 in an Aeromarine 39B.[45] On 18 November 1922, Whiting himself made the world's first catapult launch of an aircraft from an aircraft carrier while aboard Langley, piloting a Naval Aircraft Factory PT[46][47] while Langley was at anchor in Virginia's York River.[48]

Whiting was credited with establishing many basic tenets of carrier aviation, largely worked out during his first Langley tour. He established the first pilot ready rooms aboard Langley.[49] He had a hand-cranked movie camera film every landing on the carrier to aid in the evaluation of landing techniques,[50] and had a darkroom and photography laboratory installed on board to allow the landing films to be developed at sea.[51] Langley's pilots had no signaling system with which shipboard personnel could assist them in landing,[52] so when not flying himself, Whiting observed all landings from the aft port corner of Langley's flight deck.[53] where he was visible to pilots in critical touchdown attitudes when the nose of the aircraft might obscure their view straight ahead as they approached the ship to land. Pilots found Whiting's body language helpful and suggested an experienced pilot be assigned to occupy that position as a "landing signal officer" or "landing safety officer" (LSO), using signals to guide them to safe landings. In an advanced form, the LSO concept survives aboard aircraft carriers to this day.[54] Whiting also was influential in the U.S. Navy's decision to make pilot qualification a requirement for command of an aircraft carrier.[55]

Later duties

In July 1924, Whiting returned to duty at the Bureau of Aeronautics to serve as its assistant chief. Later he became head of the Aircraft Carriers Division.[56] In September 1926, he reported to the Brown-Boveri Electric Company in Camden, New Jersey, to oversee the construction of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3), which was commissioned in 1927 as the second American aircraft carrier and the first one capable of operating with the battle fleet. He became her first executive officer on 16 November 1927, remaining in that position until May 1929.[57]

Whiting was promoted to captain on 1 July 1929. He became aide and chief of staff to Commander, Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, in September 1929.[58]

In August 1930, Whiting took command of Naval Air Station Norfolk at Norfolk, Virginia. In June 1932, he departed Norfolk for Newport, Rhode Island, where he attended the Naval War College and received instruction at the Naval Torpedo Station.[59] He returned to USS Langley as her commanding officer on 15 June 1933, leaving her in December 1933 to fit out the new aircraft carrier USS Ranger (CV-4) at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. He left Ranger in 1934 to assist in developing plans for the new aircraft carriers USS Yorktown (CV-5) and USS Enterprise (CV-6). In June 1934 he returned to USS Saratoga to serve as her commanding officer.[60]

Whiting left Saratoga in July 1935 and next became Commander, Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, serving simultaneously as commander of Fleet Air Base Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii. In September 1937, he became commanding officer of Patrol Wing 2, remaining in that position until 3 June 1938.[61]

On 14 July 1939, Whiting reported for duty as General Inspector of Naval Aircraft, Eastern Division, in the Third Naval District at New York, New York. He was still in this position when he was placed on the retirement list on 30 June 1940. However, instead of retiring, he was retained on active duty.[62]

World War II

After the United States entered World War II on 7 December 1941, Whiting continued his general inspector duties until 19 February 1943, when he took command of Naval Air Station New York in Brooklyn, New York, serving also as District Aviation Officer, Third Naval District. He held these posts until his death. [63]

Death

Whiting was suffering from pneumonia and hospitalized at the National Naval Medical Center [64] in Bethesda, Maryland, when he died of a heart attack on 24 April 1943.[65] Among the honorary pallbearers at his funeral in Larchmont, New York, on 27 April 1943 were Undersecretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics Rear Admiral John S. McCain, Sr., Rear Admiral George D. Murray, and Harry Frank Guggenheim.[66]

In accordance with Whiting's wishes, his ashes were buried at sea off the Execution Rocks[67] in the deepest part of Long Island Sound.[68][69]

Commemoration

Naval Air Station Whiting Field near Milton in Santa Rosa County, Florida, is named for Whiting. His widow, Edna Andresen Whiting,[70] was among 1,500 people who attended its commissioning on 16 July 1943.[71] A plaque there reads: ""Whiting Field, named in honor of Capt. Kenneth Whiting, U.S. Navy, Pioneer in Submarines and Aviation, Naval Aviator No. 16, Father of the Aircraft Carrier in our Navy, Died on Active Duty on April 24, 1943."[72]

One U.S. Navy ship, the seaplane tender USS Kenneth Whiting (AV-14), has been named for Whiting. Edna Andresen Whiting served as sponsor during the ship's launching ceremonies on 15 December 1943. The ship served in the latter stages of World War II in 1944-1945, in the Korean War in 1952-1953, and then in the Cold War until 1958.[73]

Whiting was inducted into the Naval Aviation Hall of Honor at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, in 1984.

Awards & Decorations

Photo gallery

Kenneth Whiting undergoing flight training at the Wright Company in Dayton, Ohio, in 1914.

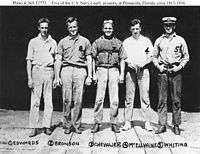

Kenneth Whiting is at far right in this photograph of five early American naval aviators at the Naval Aeronautic Station in Pensacola, Florida.

Real Admiral Ernest J. King, USN, and Captain Kenneth Whiting, USN, at French Frigate Shoals in the Hawaiian Islands in 1937.

See also

Notes

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, April 1943.

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, April 1943.

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, April 1943.

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, April 1943.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library: Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships at http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/k2/kenneth_whiting.htm

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Navsource.org Kenneth Whiting.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships at http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/a1/a-6.htm.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- NavSource.org Kenneth Whiting

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- NavSource.org Kenneth Whiting

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log, July 2011, p. 21.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Layman, p. 116.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Naval History and Heritage Command Naval Aviation Chronology 1917-1919. Archived 2010-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ResourceLibrary.comn Review by Sherman N. Mullin of Stalking the U-Boat: U.S. Naval Aviation in World War I by Geoffrey L. Rossano.

- American Military and Naval History USN Northern Bombing Group I

- Naval History and Heritage Command Naval Aviation Chronology 1917-1919. Archived 2010-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Naval History and Heritage Command Naval Aviation Chronology 1917-1919. Archived 2010-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships at http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/k2/kenneth_whiting.htm

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, April 1943.

- NavSource.org Kenneth Whiting

- Layman, p. 116.

- Layman, R.D., Before the Aircraft Carrier: The Development of Aviation Vessels 1849-1922, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1989, ISBN 0-87021-210-9, p. 116.

- Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log, July 2011, p. 23.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Wadle, p. 13.

- Naval History and Heritage Command Naval Aviation Chronology 1917-1919. Archived 2010-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Hone and Hone, p. 81.

- Hone and Hone, pp. 94-96.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Quote from "Aircraft Caiiers: Floating Homes For Naval Planes," Literary Digest, February 18, 1922, at 1920-30.com The First Aircraft Carriers.

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294.

- Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906-1921, p. 121.

- Tate, p.66.

- Naval History Blog, U.S. Naval Institute-U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, "Navy's First Carrier Commissioned, 20 March 1922," 20 March 2011, 12:01 a.m.

- Sweeny, p. 150.

- NavSource.org Kenneth Whiting

- DCMilitary.com This Week in History 17 November 2011

- Tate, pp. 62-69

- Tate., p. 68.

- Tate, pp. 62-69.

- Tate, p.68.

- Tate, p. 68.

- Tate, p. 68.

- Tate, pp. 62-69

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, 1943

- findagrave.com Capt Kenneth Whiting

- Larchmont Times obituary for Kenneth Whiting, April 1943

- Larchmont Times obituary for Kenneth Whiting, April 1943

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships at http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/k2/kenneth_whiting.htm

- findagrave.com Capt Kenneth Whiting

- Larchmont Times obituary of Kenneth Whiting, April 1943.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/26519181@N06/4377931374/ Flickr: NAS WHiting Field, Milton, FL.

- Kemper Memorial Park Profiles: Captain Kenneth Whiting, US Navy, 98 Park Avenue, Larchmont

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships at http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/k2/kenneth_whiting.htm

References

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here. (USS A-6)

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here. (USS Kenneth Whiting AV-14)

- Nimitz Library Special Collections and Archives Guide to the Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1914-1943 MS 294

- Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log, July 2011

- Kenneth Whiting at Find a Grave

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906-1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1985, ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Hone, Thomas C., and Trent Hone. Battleline: The United States Navy 1919–1939. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2006. ISBN 1-59114-378-0.

- Layman, R.D., Before the Aircraft Carrier: The Development of Aviation Vessels 1849-1922, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1989, ISBN 0-87021-210-9.

- Sweeney, Jerry K., ed. A Handbook of American Military History From the Revolutionary War to the Present, University of Nebraska Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-8032-9337-3 and ISBN 0-8032-9337-2.

- Tate, Jackson R., RADM, USN. "We Rode the Covered Wagon." United States Naval Institute Proceedings, October 1978.

- Wadle, Ryan David. United States Navy Fleet Problems and the Development of Carrier Aviation. Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University, August 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kenneth Whiting. |

- Video of early carrier landings aboard USS Langley (CV-1) ca. 1922 on YouTube

- Photo of Kenneth Whiting with other officers and Amelia Earhart in Hawaii, 18 March 1937

- dommagazine.com Photograph of Kenneth Whiting and other early aviators at the dedication of the Wright Brothers Memorial at Dayton, Ohio, 19 August 1940

- earlyaviators.com Photographs of Kenneth Whiting and other early aviators at the dedication of the Wright Brothers Memorial at Dayton, Ohio, 19 August 1940

- Larchmont Times 1943 obituary of Kenneth Whiting with photograph

- Photo of Kenneth Whiting

- Kenneth Whiting Papers, 1901-1943 MS 294 held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy