Katherine Oppenheimer

Katherine "Kitty" Vissering Oppenheimer (née Puening; August 8, 1910 – October 27, 1972) was a German-American biologist, botanist, and a member of the Communist Party of America. She is best known as the wife of activist Joe Dallet, and then of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II.

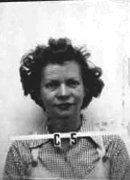

Katherine Oppenheimer | |

|---|---|

Wartime Los Alamos identification badge | |

| Born | August 8, 1910 |

| Died | October 27, 1972 (aged 62) Panama City, Panama |

| Resting place | ashes scattered at sea off Carval Rock, near Saint John, U.S. Virgin Islands |

| Other names | Katherine Puening, Katherine Ramseyer, Katherine Dallet, Katherine Harrison |

| Alma mater | |

| Political party | Communist Party of America |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2 |

Early life

Katherine "Kitty" Vissering was born in Recklinghausen, Germany, on August 8, 1910, the only child of Franz Puening and his wife Käthe Vissering. Although she claimed that her father was a prince and that her mother was related to Queen Victoria, this was untrue. Her mother was a cousin of Wilhelm Keitel, who later became a field marshal in the German Army during World War II, and was hanged in 1946.[1][2]

Kitty arrived in the United States on May 14, 1913 aboard the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. Her father, a metallurgical engineer, had invented a new kind of blast furnace, and had landed a position with a steel company in Pittsburgh, and the family settled in the suburb of Aspinwall, Pennsylvania. Although her first language was German, she soon became fluent in English, speaking both languages without accent. Her parents regularly took her with them on summer visits to Germany.[1][2]

After graduating from Aspinwall High School in June 1928, Kitty enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh.[3] She lived at home and attended freshman classes in mathematics, biology and chemistry. Her father now worked for Koppers, and held patents for the design of blast furnaces.[4][5][6] Kitty convinced her parents that it would be a good idea for her to study in Germany for a time, and she sailed for Europe in March 1930. It is doubtful that she took any classes, but she did meet Frank Ramseyer, an American studying music in Paris under Nadia Boulanger, before sailing for home on 19 May.[6]

Kitty completed the first year of her degree, but married Ramseyer before a Justice of the Peace in Pittsburgh on 24 December 1932. The couple moved to an apartment near Harvard University, where Ramseyer hoped to pursue a master's degree in music. However, she re-enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh in January 1933, and returned to her parents' house in Aspinwall. In June 1933 she sailed to Europe again, with her husband. When she returned, she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, although there is no record of her ever completing any classes. She obtained an annulment of her marriage from the Superior Court of Wisconsin on 20 December 1933. She later told friends that she had discovered evidence that Ramseyer was a homosexual and a drug addict. She also had an abortion.[7]

Communism

At a New Year's Eve party later that year, Kitty met Joseph Dallet, Jr., the son of a wealthy Long Island businessman who had attended Dartmouth College. He had been radicalized by the 1927 executions of Sacco and Vanzetti, and had joined the Communist Party of America in 1929. He had been involved in the International Unemployment Day protest in Chicago on 6 March 1930 that had been brutally repressed by the authorities, and was currently working as a union organizer with the steel workers in Youngstown, Ohio. At one point he ran for mayor of Youngstown on the Communist Party ticket, but was not elected.[8][9]

Kitty's parents had moved to Claygate, southwest of London, where her father represented a Chicago-based firm. On returning to the United States on 3 August 1934 after visiting family in Europe, she moved in with Dallet, becoming his common-law wife. They shared a room in a dilapidated boarding house that cost $5 per month. Gus Hall and John Gates had a room down the hall. They lived on the dole, $12.50 per month each, while Dallet protested against it. As the wife of a party member, Kitty was allowed to join the Communist Party, but only after proving her loyalty by hawking copies of the Daily Worker on the streets. Her party dues were 10c a week.[10][8]

They separated in June 1936, and Kitty went to live with her parents in Claygate, where she found some work as a German-to-English translator.[10] Months went by without any word from Dallet, until Kitty discovered that her mother had been hiding his letters to her. "Her mother," her friend Anne Wilson recalled, "was a real dragon, a very repressive woman. She disappeared one day over the side of a transatlantic ship, and nobody missed her. That says it all."[11]

The last letter from Dallet said that he was heading to Spain on the RMS Queen Mary to join the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War.[10][8] Kitty met up with Dallet and his best friend Steve Nelson in Cherbourg, and they travelled to Paris together. After a few days there, she returned to London, and they headed south, to cross into Spain[12] where he joined the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, a unit made up of American and Canadian volunteers.[13]

Kitty wanted to join Dallet in Spain, and finally secured permission to do so; but her trip to Spain was delayed by her hospitalization for an operation on 26 August 1937 for what was initially thought to be appendicitis, but which was determined to be ovarian cysts, which were removed by the German doctors. Kitty returned to England to recuperate. Before she could set out for Spain, the news arrived that Dallet had been killed in action on 17 October 1937. His letters to her were published as Letters from Spain by Joe Dallet, American Volunteer, to his Wife (1938).[13][14]

Kitty went to see Nelson, who was in Paris, having been wounded in August, and they returned to New York, where she stayed with Nelson and his wife Margaret at their home in Brooklyn for two months. She then headed for Philadelphia to see her friend Zelma Baker, who worked at the Cancer Research Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. Kitty enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania. It was there that she met Richard Stewart Harrison, a medical doctor with degrees from Oxford University, who was completing his internship in the United States. They were married on 23 November 1938.[15][16]

Romance with Oppenheimer

Soon after, Harrison left for Pasadena, California, for his residency at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), while Kitty completed her bachelor's degree in botany at the University of Pennsylvania, and was offered a postgraduate research fellowship at the University of California, Los Angeles.[15][16] At Caltech, Harrison worked with the physicist Charles Lauritsen; the X-Ray laboratory at Caltech used for physics research was also used for experimental cancer therapy research. It was at a garden party thrown by Lauritsen and his wife Sigrid in August 1939 that Kitty met Robert Oppenheimer, a physicist who taught at Caltech for part of each year.[17] Soon after, Kitty began an affair with Robert. They were frequently seen about town in his Chrysler coupe.[18] Robert had dated several women since his break up with long-time girlfriend Jean Tatlock, some of them married, like Kitty. At Christmas time she went up to Berkeley without her husband, to spend time with Robert. His friend Haakon Chevalier met Kitty at a holiday dinner party thrown by the pianist Estelle Caen, one of Robert's ex-girlfriends.[19]

Robert invited Harrison and Kitty to spend the summer at his New Mexico ranch, Perro Caliente. Harrison declined, as he was engaged in his research, but Kitty accepted. Robert Serber and his wife Charlotte collected Kitty in Pasadena, and drove her to Perro Caliente, where they met up with Robert, his brother Frank Oppenheimer, and his wife Jackie.[20] The Serbers had met Kitty before, at Charlotte Serber's parents' house in Philadelphia in 1938.[21] The Oppenheimers loved to ride through the pine and birch forests and floral meadows of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, camping with minimal food and equipment. Kitty impressed them with her riding ability; horsemanship was a normal accomplishment for women of her social class, and she had learned to ride as a girl on the riding trails around Aspinwall. Kitty and Robert rode out to stay the night with his friend Katy Page in Los Pinos, New Mexico. The following day Page rode to Perro Caliente on her bay horse to return Kitty's night gown, which had been left under Robert's pillow.[22][20]

Kitty later told Anne Wilson that she got Robert to marry her the "old-fashioned way"—by getting pregnant.[23] In September 1940, Robert phoned Harrison with the happy news, and they agreed that the best way forward was for Kitty to get a divorce so she could marry Robert. Soon after, Robert shared a podium with Nelson to raise money for refugees from the Spanish Civil War, and he informed him that he was engaged to Kitty. Nelson's wife was also pregnant, and he named his daughter, who was born in November 1940, Josie in memory of Dallet. To obtain a divorce, Kitty moved to Reno, Nevada, where she stayed for six weeks to meet the state's residency requirements. The divorce was finalised on November 1, 1940, and Kitty married Robert the following day in a civil ceremony in Virginia City, Nevada, with the court janitor and clerk as witnesses.[24]

Manhattan Project

Their child, a son they called Peter, was born in Pasadena, on May 12, 1941, during Robert's regular session at Caltech. When they returned to Berkeley, he bought a new house at One Eagle Hill with a view over the Golden Gate. Kitty worked at the University of California as a laboratory assistant. They left Peter with the Chevaliers and a German nurse and headed out to Perro Caliente for the summer. The holiday was marred when Robert was trampled by a horse, and Kitty was injured when she had an accident in their Cadillac convertible.[25][26] The United States entered World War II in December 1941, and Robert began recruiting staff for the Manhattan Project. Among the first were the Serbers, who moved into the apartment over the garage at One Eagle Hill.[27]

On March 16, 1943, the couple boarded a train for Santa Fe, New Mexico. By the end of the month, they had moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where they occupied one of the buildings formerly belonging to the Los Alamos Ranch School. Los Alamos was known to the occupants as "the Hill" and to the Manhattan Project as Site Y. Robert became the director of Project Y.[28] Kitty abdicated the role of post commander's wife to Martha Parsons, the wife of Robert's deputy, Navy Captain William S. Parsons.[29] She put her biologist training to use working for the director of the Health Group at Los Alamos, Louis H. Hempelmann, conducting blood tests to assess the danger of radiation.[30]

In 1944, Kitty became pregnant again. Her second child, a girl Katherine who she named after her mother but called Toni, was born on December 7, 1944. Like other babies born in wartime Los Alamos, Toni's birth certificate gave the place of birth as P.O. Box 1663.[31] In April 1945, Kitty was depressed by the isolation of Los Alamos, and she left Toni with Pat Sherr, the wife of physicist Rubby Sherr; Pat had recently lost her son, Michael, to SIDS. Kitty returned with Peter to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania to live with her parents. They returned to Los Alamos in July 1945.[32][33]

Later life

With the end of the war in August 1945, Robert had become a celebrity, and Kitty had become an alcoholic. She suffered a series of bone breaks from drunken falls and car crashes.[34][35] In November 1945, Robert left Los Alamos to return to Caltech,[36] but he soon found that his heart was no longer in teaching.[37] In 1947, he accepted an offer from Lewis Strauss to take up the directorship of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.[38] The job came with rent-free accommodation in the director's house, a ten-bedroom 17th-century manor with a cook and groundskeeper, surrounded by 265 acres (107 ha) of woodlands. Robert had a greenhouse built for Kitty, where she raised orchids; for her birthdays Robert had rare species flown in from Hawaii.[39][40] Olden Manor was sometimes known as "Bourbon Manor";[41] Kitty and Robert liked to keep the liquor cabinet well stocked, and like many of their generation, liked to celebrate cocktail hour with martinis, Manhattans, Old Fashioneds and highballs. Both were also fond of smoking,[42] and Kitty's habit of combining too much alcohol with smoking in bed led to a plethora of holes in her bedding and at least one house fire.[35] She sometimes took too many pills, and suffered from abdominal pains caused by pancreatitis. Pain often prompted outbursts of anger.[43]

In 1952, Toni came down with polio, and doctors suggested that a warmer climate might help. The family flew down to the Caribbean, where they rented a 72-foot (22 m) ketch. Robert and Kitty discovered a mutual love of sailing, while Toni soon recovered. Henceforth, the family would spend part of each summer on Saint John in the Virgin Islands, eventually building a beach house there.[44] On January 6, 1967, Robert was diagnosed with inoperable cancer, and he died on February 18, 1967.[45] Kitty had his remains cremated and his ashes were placed in an urn, which she took to St. John and dropped them into the sea off the coast, within sight of the beach house.[46] She took up with Robert Serber, whose wife Charlotte had committed suicide in May 1967. She talked him into buying a 52-foot (16 m) yawl, which they sailed from New York to Grenada. In 1972, they purchased a 52-foot (16 m) ketch, with the intention of sailing through the Panama Canal and to Japan via the Galapagos Islands and Tahiti. They set out, but Kitty became ill, and was taken to Gorgas Hospital, where she died of an embolism on October 27, 1972. Serber and Toni had her remains cremated, and they scattered her ashes near Robert's.[47][48][49]

References

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 154–155.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 9–10, 26–27.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 42–43.

- US 1542955 Heating method and apparatus

- US 1799702 Heating apparatus

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 78–79.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 80–82.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 156–157.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 89–90.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 93–94, 97–98.

- Conant 2005, p. 184.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 104–105.

- "Joseph Dallet, Jr". Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 111–117.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 119.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 158–161.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 120–121.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 161.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 125–126.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 162.

- Serber & Crease 1998, p. 51.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 128–129.

- Conant 2005, p. 186.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 162–163.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 164–165.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 138–139.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 141–142.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 213–214.

- Conant 2005, p. 179.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 51.

- Conant 2005, pp. 262–263.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 204–211.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 263–264.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 207.

- Wolverton 2008, p. 176.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 333–335.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 351.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, pp. 360–365.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 369.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 234–235.

- Wolverton 2008, p. 270.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 243.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 276.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 251.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, p. 295.

- Bird & Sherwin 2005, p. 588.

- Streshinsky & Klaus 2013, pp. 301–302.

- Serber & Crease 1998, pp. 220–221.

- "Mrs. J. Robert Oppenheimer, 62, Nuclear Physicist's Widow, Dies". New York Times. October 29, 1972. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

Sources

- Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41202-6. OCLC 56753298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conant, Jennet (2005). 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5007-9. OCLC 57475908.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Serber, Robert; Crease, Robert P. (1998). Peace & War: Reminiscences of a Life on the Frontiers of Science. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10546-0. OCLC 1014748640.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Streshinsky, Shirley; Klaus, Patricia (2013). An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer's Life. New York: Turner Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61858-019-1. OCLC 849822662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolverton, Mark (2008). A Life in Twilight: The Final Years of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-37440-2. OCLC 223882887.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)