SS-Junker Schools

SS-Junker Schools (German SS-Junkerschulen) were leadership training facilities for SS-Junkers, officer candidates of the Schutzstaffel (SS). The term Junkerschulen was introduced by Nazi Germany in 1937, although the first facilities were established at Bad Tölz and Braunschweig in 1934 and 1935. Additional schools were founded at Klagenfurt and Posen-Treskau in 1943, and Prague in 1944. Unlike the Wehrmacht's "war schools", admission to the SS-Junker Schools did not require a secondary diploma. Training at these schools provided the groundwork for employment with the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo; security police), the Sicherheitsdienst (SD; security service), and later for the Waffen-SS. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler intended for these schools to mold cadets for future service in the officer ranks of the SS.[1][2]

History

As part of an effort to professionalize their officers, the SS founded a Leadership School in 1934; the first one was at the Bavarian town of Bad Tölz, established under the leadership of SS-Colonel Paul Lettow. Thereafter, a second school at Braunschweig under the direction of then SS-Oberführer Paul Hausser was founded.[3] Hausser's military experience and detailed knowledge as a retired army lieutenant general was leveraged by Himmler in developing the curriculum at both the Bad Tölz and Braunschweig training centers.[4] To his staff, Hausser added other experienced military veterans and gifted officers to build a training regimen that became the foundation for the Waffen-SS.[5]

In 1937, Himmler rechristened the Leadership Schools to "Junker Schools" in honor of the land-owning Junker aristocracy that once dominated the Prussian military. Akin to the Junker officers of their namesake, most cadets eventually led Waffen-SS regiments into combat.[6] By the time World War II in Europe was underway, additional SS Leadership Schools at Klagenfurt, Posen-Treskau and Prague had been founded.[7]

Himmler intended to use the SS-Junker Schools to help instill the SS ethic into Nazi Germany's police forces.[8] To accomplish this, a percentage of SS-Junker School graduates entered the ranks of the Uniformed Police; in 1937, some 40 percent of Junker School-graduates joined the police, and another 32 percent were integrated into the police in 1938.[8] Suitable members of the Hitler Youth were identified, as were students who had successfully completed their Abitur (university entrance exam) for application into the SS-Junker Schools or they could elect to attend Nazi Germany's police officer candidate schools.[9] Graduates and affiliates of the SS-Junker Schools were among those persons given the Hitler Sondergerichtsbarkeit (special jurisdiction), which freed them from prosecution for criminal acts.[10] Also included in this extrajudicial group were the likes of the Gestapo, the SiPO, and the SD.[11]

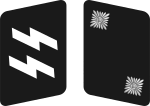

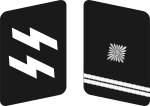

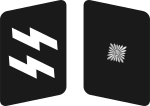

- Rank insignia

| Collar pach | Soulder strap | Camouflage clothing | Rank designation | Equivalent (NCO-rank Waffen-SS) | Shoulder starp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SS-Standartenoberjunker | SS-Hauptscharführer | |||

|

SS-Standartenjunker | SS-Oberscharführer | |||

|

SS-Oberjunker | SS-Scharführer | |||

|

SS-Junker | SS-Unterscharführer |

Training

Created to educate and mold the next generation of leadership within the SS, cadets were taught to be adaptable officers who could perform any task assigned to them, whether in a police role, at a Nazi concentration camp, as part of a fighting unit, or within the greater SS organization.[12] Additional administrative and economic training was included at the behest of SS-Gruppenführer Oswald Pohl and the SS Main Economic and Administrative Department. Pohl intended to shape future SS officers into effective and efficient managers of the SS economics industry and insisted that supplemental training in corporate operations was integrated into the curriculum.[6]

General military instruction over logistics and planning was provided but much of the training concentrated on small-unit tactics associated with raids, patrols, and ambushes.[13] Training an SS officer took as much as nineteen months overall and encompassed additional things like map reading, tactics, military maneuvers, political education, weapons training, physical education, combat engineering and even automobile mechanics, all of which were provided in varying degrees at additional training facilities based on the cadet’s specialization.[14]

Political and ideological indoctrination was part of the syllabus for all SS cadets but there was no merger of academic learning and military instruction like that found at West Point in the United States.[15] Instead, personality training was stressed, which meant future SS leaders/officers were shaped above all things by a National Socialist worldview and attitude. Instruction at the Junker Schools was designed to communicate a sense of racial superiority, a connection to other dependable like-minded men, ruthlessness, and a toughness that accorded the value system of the SS. Throughout their stay during the training, cadets were constantly monitored for their "ideological reliability."[16] It is postulated that the merger of the police with the SS was at least partly the result of their shared attendance at the SS Junker Schools.[17] By 1945, more than 15,000 cadets from these training institutions were commissioned as officers in the Waffen-SS.[18]

References

Citations

- Snyder 1976, p. 187.

- Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 480.

- Weale 2012, p. 206.

- Gilbert 2019, p. 21.

- Gilbert 2019, p. 22.

- Allen 2002, p. 112.

- Pine 2010, p. 89.

- Westermann 2005, p. 99.

- Westermann 2005, p. 100.

- Ziegler 1989, pp. 40–41.

- Ziegler 1989, p. 41.

- Weale 2012, pp. 206–207.

- Weale 2012, p. 207.

- Weale 2012, pp. 207–208.

- Weale 2012, p. 209.

- Mineau 2011, p. 29.

- Laqueur & Baumel 2001, p. 606.

- Gilbert 2019, p. 25.

Bibliography

- Allen, Michael Thad (2002). The Business of Genocide: The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps. London and Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80782-677-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilbert, Adrian (2019). Waffen-SS: Hitler’s Army at War. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-30682-465-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laqueur, Walter; Baumel, Judith Tydor (2001). The Holocaust Encyclopedia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30008-432-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mineau, André (2011). SS Thinking and the Holocaust. New York: Editions Rodopi. ISBN 978- 9401207829.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pine, Lisa (2010). Education in Nazi Germany. New York: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-265-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snyder, Louis L (1976). Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-1-56924-917-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York: Caliber Printing. ISBN 978-0451237910.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Westermann, Edward B. (2005). Hitler's Police Battalions: Enforcing Racial War in the East. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1724-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1991). The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-897500-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ziegler, Herbert F. (1989). Nazi Germany's New Aristocracy: The SS Leadership, 1925–1939. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05577-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)