Juggling

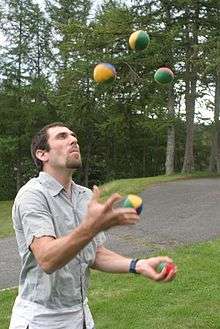

Juggling is a physical skill, performed by a juggler, involving the manipulation of objects for recreation, entertainment, art or sport. The most recognizable form of juggling is toss juggling. Juggling can be the manipulation of one object or many objects at the same time, most often using one or two hands but also possible with feet. Jugglers often refer to the objects they juggle as props. The most common props are balls, clubs, or rings. Some jugglers use more dramatic objects such as knives, fire torches or chainsaws. The term juggling can also commonly refer to other prop-based manipulation skills, such as diabolo, plate spinning, devil sticks, poi, cigar boxes, contact juggling, hooping, yo-yo, and hat manipulation.

Etymology

The words juggling and juggler derive from the Middle English jogelen ("to entertain by performing tricks"), which in turn is from the Old French jangler. There is also the Late Latin form joculare of Latin joculari, meaning "to jest".[1] Although the etymology of the terms juggler and juggling in the sense of manipulating objects for entertainment originates as far back as the 11th century, the current sense of to juggle, meaning "to continually toss objects in the air and catch them", originates from the late 19th century.[2][3]

From the 12th to the 17th century, juggling and juggler were the terms most consistently used to describe acts of magic, though some have called the term juggling a lexicographical nightmare, stating that it is one of the least understood relating to magic. In the 21st century, the term juggling usually refers to toss juggling, where objects are continuously thrown into the air and caught again, repeating in a rhythmical pattern.[2][4][5]

According to James Ernest in his book Contact Juggling, most people will describe juggling as "throwing and catching things"; however, a juggler might describe the act as "a visually complex or physically challenging feat using one or more objects".[6] David Levinson and Karen Christensen describe juggling as "the sport of tossing and catching or manipulating objects [...] keeping them in constant motion".[7] "Juggling, like music, combines abstract patterns and mind-body coordination in a pleasing way."[8]

Origins and history

Ancient to 20th century

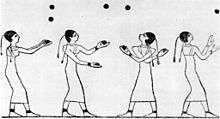

The earliest record of juggling is suggested in a panel from the 15th (1994 to 1781 B.C.) Beni Hasan tomb of an unknown Egyptian prince, showing female dancers and acrobats throwing balls.[10] Juggling has been recorded in many early cultures including Egyptian, Nabataean, Chinese, Indian, Greek, Roman, Norse, Aztec (Mexico) and Polynesian civilizations.[11][12][13]

Juggling in ancient China was an art performed by some warriors. One such warrior was Xiong Yiliao, whose juggling of nine balls in front of troops on a battlefield reportedly caused the opposing troops to flee without fighting, resulting in a complete victory.[14]

In Europe, juggling was an acceptable diversion until the decline of the Roman Empire, after which the activity fell into disgrace. Throughout the Middle Ages, most histories were written by religious clerics who frowned upon the type of performers who juggled, called gleemen, accusing them of base morals or even practicing witchcraft. Jugglers in this era would only perform in marketplaces, streets, fairs, or drinking houses. They would perform short, humorous and bawdy acts and pass a hat or bag among the audience for tips. Some kings' and noblemen’s bards, fools, or jesters would have been able to juggle or perform acrobatics, though their main skills would have been oral (poetry, music, comedy and storytelling).

In 1768, Philip Astley opened the first modern circus. A few years later, he employed jugglers to perform acts along with the horse and clown acts. Since then, jugglers have been associated with circuses.

In the early 19th century,[15] troupes from Asia, such as the famous "Indian Jugglers"[16] referred to by William Hazlitt,[17] arrived to tour Britain, Europe and parts of America.[18]

In the 19th century, variety and music hall theatres became more popular, and jugglers were in demand to fill time between music acts, performing in front of the curtain while sets were changed. Performers started specializing in juggling, separating it from other kinds of performance such as sword swallowing and magic. The Gentleman Juggler style was established by German jugglers such as Salerno and Kara. Rubber processing developed, and jugglers started using rubber balls. Previously, juggling balls were made from balls of twine, stuffed leather bags, wooden spheres, or various metals. Solid or inflatable rubber balls meant that bounce juggling was possible. Inflated rubber balls made ball spinning easier and more readily accessible. Soon in North America, vaudeville theatres employed jugglers, often hiring European performers.

20th century

In the early to mid-20th century, variety and vaudeville shows decreased in popularity due to competition from motion picture theatres, radio and television, and juggling suffered as a result. Music and comedy transferred very easily to radio, but juggling could not. In the early years of TV, when variety-style programming was popular, jugglers were often featured; but developing a new act for each new show, week after week, was more difficult for jugglers than other types of entertainers; comedians and musicians can pay others to write their material, but jugglers cannot get other people to learn new skills on their behalf.

The International Jugglers' Association, founded in 1947, began as an association for professional vaudeville jugglers, but restrictions for membership were eventually changed, and non-performers were permitted to join and attend the annual conventions. The IJA continues to hold an annual convention each summer and runs a number of other programs dedicated to advance the art of juggling worldwide.

World Juggling Day was created as an annual day of recognition for the hobby, with the intent to teach people how to juggle, to promote juggling and to get jugglers together and celebrate. It is held on the Saturday in June closest to the 17th, the founding date of the International Jugglers' Association.[19]

Most cities and large towns now have juggling clubs. These are often based within, or connected to, universities and colleges. There are also community circus groups that teach young people and put on shows. The Juggling Edge[20] maintains a searchable database of most juggling clubs.

Since the 1980s, a juggling culture has developed. The scene revolves around local clubs and organizations, special events, shows, magazines, web sites, internet forums and, possibly most importantly, juggling conventions. In recent years, there has also been a growing focus on juggling competitions. Juggling today has evolved and branched out to the point where it is synonymous with all prop manipulation. The wide variety of the juggling scene can be seen at any juggling convention.

Juggling conventions or festivals form the backbone of the juggling scene. The focus of most of these conventions is the main space used for open juggling. There will also be more formal workshops in which expert jugglers will work with small groups on specific skills and techniques. Most juggling conventions also include a main show (open to the general public), competitions, and juggling games.

Popular forms

Juggling can be categorised by various criteria:

- Professional or amateur

- Juggling up until the latter half of the 20th century has been principally practised as a profession. Since the 1960s, and even more so from the 1980s, juggling has also been practiced as a hobby. The popularity of juggling acts performing outside the circus has meant an increase in the number of professional jugglers in the last thirty years. Festivals, fairs, retail promotions and corporate events have all booked juggling acts. The increase in hobby juggling has resulted in juggling stores opening and numerous juggling conventions being run to fulfill the needs of an increasingly popular pastime.

- Objects juggled

- Balls, clubs, rings, diabolos, devil sticks and cigar boxes are several types of objects that are commonly juggled. Other objects, such as scarves, knives, fruits and vegetables, flaming torches and chainsaws, have also been used.

- Method of juggling

- The best known type of juggling is toss juggling, which is throwing and catching objects in the air without the objects touching the ground. Bounce juggling is bouncing objects (usually balls) off the ground. Contact juggling is manipulating the object in constant contact with the body. One division of juggling by method is into toss, balancing (equilibristics), gyroscopic (spin), and contact juggling.[21]

- Trick juggling

- This type of juggling involves performing tricks of varying levels of difficulty. The tricks can use the basic patterns of toss juggling but add more difficult levels of object manipulation. Other tricks can be independent of these basic patterns and involve other variations of object manipulation.

- Number of objects juggled

- Numbers juggling is the goal of juggling as many objects as possible. This is often the initial goal of beginner jugglers, as it is commonly seen in the circus and stage juggling acts. Numbers juggling records are noted by a number of organisations.

- Number of jugglers

- Juggling is most commonly performed by an individual. However, multiple-person juggling is also popular and is performed by two or more people. Various methods of passing the objects between the jugglers is used — this can be through the air (as in toss juggling), bounced off the ground, simply handed over, or a number of other ways depending on the objects and the style of juggling. For example, one variation is where two club jugglers stand facing each other, each juggling a three-club pattern themselves, but then simultaneously passing between each other. Another variation is where the jugglers are back-to-back, and (usually) any passes to the other person travel over their heads.

- Sport (competitive) juggling

- Juggling has more recently developed as a competitive sport by organizations such as the World Juggling Federation. Sport juggling competitions reward pure technical ability and give no extra credit for showmanship or for juggling with props such as knives or torches. Albert Lucas created the first sport juggling organization in the early nineties − the International Sport Juggling Federation,[22] which promotes joggling and other athletic forms of juggling.

World records

There is no organisation that tracks all juggling world records.

Toss juggling and club passing world records used to be tracked by the Juggling Information Service Committee on Numbers Juggling (JISCON) (now defunct).[23] Some records are tracked by Guinness World Records.

The most footballs (soccer balls) juggled simultaneously is five and was achieved by Victor Rubilar (Argentina) at the Gallerian Shopping Centre in Stockholm, Sweden, on 4 November 2006. This was equaled by Marko Vermeer (Netherlands) in Amstelveen, Netherlands, on 11 August 2014 and Isidro Silveira (Spain), in Adeje, Tenerife, Spain, on 4 November 2015.[24]

Performance

Style

Professional jugglers perform in a number of different styles, which are not mutually exclusive. These juggling styles have developed or been introduced over time with some becoming more popular at some times than others.

Circus juggling

Traditional circus-style juggling emphasises high levels of skill and sometimes large-scale props to enable the act to "fill" the circus ring. The juggling act may involve some comedy or other circus skills such as acrobatics, but the principal focus is the technical skill of the jugglers. Costumes are usually colourful with sequins. Variations within this style include the traditions from Chinese and Russian circus.

Comedy juggling

Comedy juggling acts vary greatly in their skill level, prop use and costuming. However, they all share the fact that the focus of the performance is comedic rather than a demonstration of technical juggling skill. Comedy juggling acts are most commonly seen in street performance, festivals and fairs.

Gentleman juggling

Gentleman juggling was popular in variety theatres and usually involves juggling some of the elements of a gentleman's attire, namely hats, canes, gloves, cigars, and other everyday items[25] such as plates and wine bottles.[26] The style is often sophisticated and visual rather than comedic, though it has been interpreted in many different styles. French juggler Gaston Palmer, for example, gained a kind of notoriety for his comedic execution of gentleman juggling tricks.[27]

Themed juggling

Jugglers perform themed acts, sometimes with specifically themed props and usually in themed costumes. Examples include jesters, pirates, sports, Victorians and chefs.

Venues

Circus

Jugglers commonly feature in circuses, with many performers having enjoyed a star billing. Circus jugglers come from many countries and include those from Russia and other Eastern European countries, China, Latin America and other European countries. Some of the greatest jugglers from the past 50 years are from Eastern Europe, including Sergej Ignatov, Andrii Kolesnikov, Evgenij Biljauer, and Gregory Popovich.

Variety theatres

Variety theatres have a long history of including juggling acts on their billing. Vaudeville in the USA and Music halls in the UK regularly featured jugglers during the heyday of variety theatre in the first half of 20th century. Variety theatre has declined in popularity but is still present in many European countries, particularly Germany. Television talent shows have introduced juggling acts to a wider audience with the newest examples being Britain's Got Talent and America's Got Talent.

Casinos

In North America jugglers have often performed in casinos, in places like Las Vegas. Germany and the United States have produced some of the greatest jugglers from the past 50 years, most notably Francis Brunn from Germany and Anthony Gatto from the United States.

Festivals and fairs

There is a wide variety of festivals and fairs where juggling acts are sometimes booked to perform. Music, food and arts festivals have all booked professional performers. The festivals can range from very large scale events such as Glastonbury Festival to small town or village fairs. The acts may differ from year to year or a one-act may become a regular feature at these yearly events.

Historically themed events

Renaissance fairs in North America and medieval fairs in Europe often book professional jugglers. Other historically themed events such as Victorian, maritime, and large-scale festivals of history such as the one organised by English Heritage regularly employ juggling acts as part of the event.

Street performance

In many countries such as the UK, USA, Australia, Spain, France jugglers perform on the street (busking). Street juggling acts usually perform what is known as a circle show and collect money at the end of the performance in a hat or bottle. Most street jugglers perform comedy juggling acts. Well known locations for this kind of street performance include Covent Garden in London, Faneuil Hall in Boston, Outside the Pump Rooms in Bath, Prince's Street in Edinburgh, outside the Pompidou Centre in Paris, Circular Quay in Sydney, and Pearl Street in Boulder.

Space

Juggling has been performed in space despite the fact that the micro-gravity environment of orbit deprives the juggled objects of the essential ability to fall. This was accomplished initially by Don Williams, as part of a Houston scientist's "Toys In Space" project, with apples and oranges.[28]

Two person juggling passing multiple objects between them was first accomplished in space by Greg Chamitoff and Richard Garriott[29] while Garriott was visiting the International Space Station as a Spaceflight Participant in October 2008. Their juggling of objects while in orbit was featured in Apogee of Fear, the first science fiction movie made in space by Garriott and 'Zero-G Magic', a magic show also recorded in space by Chamitoff and Garriott at that time.

Health benefits

According to an Oxford University study, juggling improves cerebral connectivity performance.[30][31]

Notable jugglers

- Anthony Gatto

- Albert Lucas

- Sergej Ignatov

- Air Jazz[32]

- Francis Brunn & Lotti Brunn

- Bobby May

- Enrico Rastelli

- Paul Cinquevalli

- Michael Moschen

- Jason Garfield

- Luke Burrage

- Vova Galchenko

- Thomas Dietz

- Rudy Cardenas[33]

Mathematics

Mathematics has been used to understand juggling as juggling has been used to test mathematics. The number of possible patterns n digits long using b or fewer balls is bn and the average of the numbers in a siteswap pattern equal the number of balls required for the pattern.[10] For example, the number of three digit three ball patterns is 33 = 27, and the box, (4,2x)(2x,4), requires (4+2+4+2)/4 = 3 balls.

"The time that a ball spends in flight is proportional to the square root of the height of the throw," meaning that the number of balls used greatly increases the amount of speed or height required, which increases the need for accuracy between the direction and synchronization of throws.[10]

Coupled oscillation and synchronization ("the tendency of two limbs to move at the same frequency"[10]) appear to be easier in all patterns and also required by certain patterns. For example, "the fountain pattern...can be stably performed in two ways...one can perform the fountain with different frequencies for the two hands, but that coordination is difficult because of the tendency of the limbs to synchronize," while "in the cascade...the crossing of the balls between the hands demands that one hand catches at the same rate that the other hand throws."[10]

_ladder_diagram.svg.png)

_ladder_diagram_Shannon.svg.png)

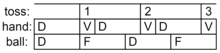

Claude Shannon, builder of the first juggling robot, developed a juggling theorem, relating the time balls spend in the air and in the hands: (F+D)H=(V+D)N, where F = time a ball spends in the air, D = time a ball spends in a hand/time a hand is full, V = time a hand is vacant, N = number of balls, and H = number of hands.[10] For example, a hand's and a ball's perspectives in the two-hand (H) three-ball (N) cascade pattern:

toss: 1st 2nd 3rd

hand: D--VD—VD—V

ball: D--F--D--F--

R L R

L R L

- (F+D)H=(V+D)N

- (3+3)2=(1+3)3

- 6×2=4×3

- 12=12

Juggling notation

Juggling tricks and patterns can become very complex, and hence can be difficult to communicate to others. Therefore, notation systems have been developed for specifying patterns, as well as for discovering new patterns.[34]

Diagram-based notations are the clearest way to show juggling patterns on paper, but as they are based on images, their use is limited in text-based communication. Ladder diagrams track the path of all the props through time, where the less complicated causal diagrams only track the props that are in the air, and assumes that a juggler has a prop in each hand. Numeric notation systems are more popular and standardized than diagram-based notations. They are used extensively in both a written form and in normal conversations among jugglers.

Siteswap is by far the most common juggling notation. Various heights of throw, considered to take specific "beats" of time to complete, are assigned a relative number. From those, a pattern is conveyed as a sequence of numbers, such as "3", "744", or "97531". Those examples are for two hands making alternating or "asynchronous" throws, and often called vanilla siteswap. For showing patterns in which both hands throw at the same time, there are other notating conventions for synchronous siteswap. There is also multiplex siteswap for patterns where one hand holds or throws two or more balls on the same beat. Other extensions to siteswap have been developed, including passing siteswap, Multi-Hand Notation (MHN), and General Siteswap (GS).

See also

- Jugglers (category)

- Flair bartending

References

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition, 1989: juggling entry.

- "Juggle", OxfordDictionaries.com.

- Rid, Samuel (1612). The Art of Iugling or Legerdemaine. Project Gutenberg.

- "Juggle", Merriam-Webster.com.

- (1983). American Heritage Dictionary. Cited in Ernest (2011), p.1.

- Ernest, James (2011). Contact Juggling, p.1. ISBN 9781591000273.

- Crego, Robert (2003). Sports and Games of the 18th and 19th Centuries, p.16. ISBN 9780313316104.

- Borwein, Jonathan M.; ed. (1997). Organic Mathematics, p.134. American Mathematical Soc. ISBN 9780821806685.

- Gillen, Billy (1986). "Remember the Force Hassan!", Juggling.org. Juggler's World: Vol. 38, No. 2.

- Beek, Peter J. and Lewbel, Arthur (1995). "The Science of Juggling Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine", Scientific American.

- "Prof. Arthur Lewbel's Research in Juggling History". .bc.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- "The JIS Museum of Juggling's Ethnography section". Juggling.org. 1995-03-13. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- Jane, Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. London, United Kingdom: I.B.Tauris. p. 41. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Chinese Acrobatics Through the Ages, by Fu Qifeng

- The Times (London, England), 27 July 1813, p.2:'The exhibition of the Indian Jugglers, at No. 87, Pall-mall, has been attended by nearly all the Families of distinction in town; and is becoming extremely popular.'

- "J. Green: The Indian Jugglers Archived 2016-08-14 at the Wayback Machine", Orientalism-in-Art.org.

- In his Table Talk (1821) Hazlitt recalled the opening routine: '... the chief of the Indian Jugglers begins with tossing up two brass balls, which is what any of us could do, and concludes with keeping up four at the same time, which is what none of us could do to save our lives... to make them revolve round him at certain intervals, like the planets in their spheres, to make them chase one another like sparkles of fire, or shoot up like flowers or meteors, to throw them behind his back and twine them round his neck like ribbons or like serpents...with all the ease, the grace, the carelessness imaginable... is skill surmounting difficulty, and beauty triumphing over skill.'

- An appearance by the leader of the Indian Jugglers troupe, Ramo Samee, is described in the Salem Gazette, 5 October 1819

- "World Juggling Day Archived 2015-06-30 at the Wayback Machine", IJA.

- "Juggling Edge - Global Juggling Clubs". JugglingEdge.com. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- Ernest (2011), p.2.

- "International Sport Juggling Federation". isjf.org. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- "JIS Numbers Juggling Records". Juggling.org. 2011-06-20. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- "Most footballs juggled". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- "Meaning and expression in juggling". Object Episodes. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- Lisenby, Ashley. "St. Louisan juggles his way into spot with Cirque du Soleil show". stltoday.com. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- "Gaston Palmer - IJA". www.juggle.org. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- Giduz, Bill (1985). "The Joy of Zero-G Juggling". Juggler's World. 37–2: 4–6.

- Chamitoff, Greg. "Greg Chamitoff's Journal". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- http://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2009-10-12-juggling-enhances-connections-brain

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8297764.stm

- Ziethen, Karl-Heinz (2003). Virtuosos of Juggling. Santa Cruz: Renegade Juggling. pp. 137–138. ISBN 0974184802.

- https://www.juggle.org/rudy-cardenas-a-living-legend/

- "Siteswap Fundamentals ⋆ Thom Wall". Thom Wall. 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

Further reading

- Dancey, Charlie 1995 Compendium of Club Juggling Butterfingers, Bath ISBN 1 898591 14 8.

- Dancey, Charlie 2001 Encyclopedia of Ball Juggling, Butterfingers, Devon ISBN 1 898591 13 X.

- Finnigan, Dave 1987 The Complete Juggler, Vintage Books, New York ISBN 0 394 74678 3.

- Summers, Kit 1987 Juggling with Finesse, Finesse Press, San Diego ISBN 0 938981 00 5.

- Ziethen, Karl-Heinz & Serena, Alessandro 2003 Virtuosos of Juggling, Renegade Juggling, Santa Cruz ISBN 0 9741848 0 2.

- Ziethen, Karl-Heinz & Allen, Andrew 1985 Juggling: The Art and its Artists, Werner Rausch & Werner Luft Inc, Berlin ISBN 3 9801140 1 5.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Learning to juggle |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Juggling. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Juggler. |

Organizations

- The International Jugglers' Association (IJA) — worldwide community of jugglers

- The European Jugglers' Association (EJA) — European community of jugglers

- The World Juggling Federation (WJF) — private company aimed at promoting competition-style juggling

- Extreme juggling — hosts yearly competitions and releases DVDs of the competitors

Resources

- Juggling Information Service - dated but has a huge amount of information (website)

- The Juggling Edge - up to date events and club listings

- r/juggling - juggling subreddit; active community

- Library of Juggling - detailed collection of toss juggling patterns

Other

- A glossary of juggling terms

- JIS Numbers Juggling Records - list of world juggling records