John F. Collins

John Frederick Collins (July 20, 1919 – November 23, 1995) was the Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts from January 4, 1960 to January 1, 1968 whose property tax assessor's office redlined the city and under whose tenure the Boston Housing Authority actively segregated its public housing developments. Collins also opposed the University of Massachusetts Boston locating its campus permanently in Park Square or elsewhere in Downtown Boston, having the Boston Redevelopment Authority propose locating the campus permanently at the former Columbia Point landfill closed in 1963 instead (and where the school would ultimately move to in 1974). His Associated Press obituary noted that the urban renewal policies Collins implemented in Boston were emulated across the United States. In 2004, nine years after his death, the city government commissioned a mural of Collins on the exterior of Boston City Hall adjacent to Government Center station and dedicated City Hall Plaza to him as well.

John F. Collins | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| 50th Mayor of Boston | |

| In office January 4, 1960[1] – January 1, 1968[2] | |

| Preceded by | John B. Hynes |

| Succeeded by | Kevin H. White |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate from the 5th Suffolk District | |

| In office 1951–1955 | |

| Preceded by | Chester A. Dolan Jr. |

| Succeeded by | James W. Hennigan Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Frederick Collins July 20, 1919 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 23, 1995 (aged 76) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. Joseph's Cemetery in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Patricia Cunniff ( m. 1946) |

| Alma mater | Suffolk University Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1941-1946 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Counterintelligence Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

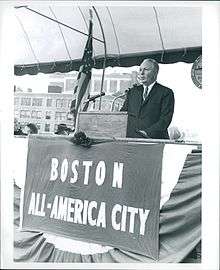

_(10695844926).jpg)

Early life

John Collins was born in Roxbury on July 20, 1919 to an Irish Catholic family.[3] His father, Frederick "Skeets" Collins, worked as a mechanic for the Boston Elevated Railway.[4] Collins graduated from Roxbury Memorial High School, and in 1941, from Suffolk University Law School.[3] He served a tour in the Army Counterintelligence Corps during World War II, rising in rank from private to captain.[3][5] He was a Knight of Columbus.[6]

In 1946, Collins married Mary Patricia Cunniff, a legal secretary, who Collins had met through his work as an attorney. She would later campaign for Collins when he was incapacitated by polio.[7] The couple had four children.

Early political career

In 1947, Collins was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, representing Jamaica Plain, and, in 1950, to the Massachusetts State Senate.[3][5] Collins spent two terms as senator and then ran unsuccessfully for state attorney general in 1954, losing to George Fingold.[3] While campaigning for a seat on the City Council in 1955, Collins and his children contracted polio. Collins' children recovered and he continued with his campaign despite warnings from his doctors.[3] As a result of the disease, Collins was forced to use a wheelchair or crutches for the rest of his life.[8] He was elected to the Council and the following year was appointed Register of Probate for Suffolk County.[3]

Mayor of Boston

In 1959, he ran against Massachusetts Senate President John E. Powers for Mayor of Boston. Collins was widely viewed as the underdog in the race.[3] Collins ran on the slogan "stop power politics", and was widely seen as independent of any political machine.[3][5] Collins' victory in the 1959 mayoral election was considered the biggest upset in city politics in decades.[9] Boston University political scientist Murray Levin wrote a book on the race, titled The Alienated Voter: Politics in Boston, which attributed Collins' victory to the voters' cynicism and resentment of the city's political elite.[10]

Collins inherited a city in fiscal distress. Property taxes in Boston were twice as high as in New York or Chicago, even as the city's tax base was declining. Collins established a close relationship with a group of local business leaders known as the Vault, cut taxes in five of his eight years in office and imposed budget cuts on city government. Collins' administration focused on downtown redevelopment: Collins brought the urban planner Edward J. Logue to Boston to lead the Boston Redevelopment Authority and Collins' administration supervised the construction of the Prudential Center complex and of Government Center.[9][11]

However, in March 1965, an investigative study of property tax assessment practices published by the National Tax Association of 13,769 properties sold within the City of Boston from January 1, 1960 to March 31, 1964 found that the assessed values in the neighborhood of Roxbury in 1962 were at 68 percent of market values while the assessed values in West Roxbury were at 41 percent of market values, and the researchers could not find a nonracial explanation for the difference.[12][13] Also under Collins' tenure as Mayor, the Boston Housing Authority segregated the public housing developments in the city as well, moving black families into the development at Columbia Point while reserving developments in South Boston for white families who started refusing assignment to the Columbia Point project by the early 1960s.[14] In 1962, upon receipt of a lawsuit filed by a civil rights group, the West Broadway Housing Development was desegregated after having been designated by the city for white-only occupancy since 1941. In the same year, the Mission Hill project had 1,024 families (all white), while the Mission Hill Extension project across the street had 580 families (of which 500 were black), and in 1967, when the city government agreed to desegregate the developments, the projects were still 97 percent white and 98 percent black respectively.[15]

In August 1965, Collins publicly requested that University of Massachusetts Boston Chancellor John W. Ryan not consider a permanent campus at its current site in Park Square or elsewhere in Downtown Boston but a suburban campus or one located in an underdeveloped section of Roxbury, while University of Massachusetts President John W. Lederle insisted on a campus inside the city limits of Boston.[16] In May 1966, following organized opposition from residents, Collins spoke with Chancellor Ryan and a proposal to locate the UMass Boston campus near Highland Park was cancelled.[17] In 1967, the Boston Redevelopment Authority proposed locating the campus permanently at the former Columbia Point landfill closed in 1963.[18][19][20] In response, in November 1967, 1,500 faculty and students organized a rally on Boston Common demanding a location in Copley Square, and before his resignation as UMass Boston Chancellor in February 1968, Ryan proposed a 15-acre campus over the Massachusetts Turnpike and south of where the proposed John Hancock Tower was to be built which the Boston Redevelopment Authority rejected.[21]

On February 28, 1963, Collins met with President John F. Kennedy at the White House.[22] Kennedy had supported John Powers during the 1959 mayoral election.[23] Collins won re-election in 1963, easily defeating City Councilor Gabriel Piemonte. However, Collins' budget priorities led to a decrease in city services, particularly in residential neighborhoods outside of downtown. As a result, Collins became unpopular among city residents. In 1966, Collins ran for the United States Senate seat being vacated by the retiring former Senate Republican Conference Whip Leverett Saltonstall, but lost in the primary to former Massachusetts Governor Endicott Peabody (who in turn would lose to Massachusetts Attorney General Edward Brooke). Despite receiving 42 percent of the vote statewide, Collins lost 21 out of Boston's 22 wards. Weakened politically, Collins declined to seek reelection in 1967 and was succeeded by Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth Kevin White.[11]

Retirement and legacy

After leaving office in 1968, Collins held visiting and consulting professorships at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for 13 years.[24] In the early 1970s, Collins drifted away from the Democratic Party. He chaired the group Massachusetts Democrats and Independents for Nixon and, in 1972, attacked Democrats for "their crazy policies of social engineering and abortion."[8] Collins was considered for the position of Secretary of Commerce in the Nixon administration.[5]

In December 1968, the UMass Boston board of trustees voted 12 to 4 to accept the Columbia Point campus proposal from the Boston Redevelopment Authority.[25] In April 1969, the Students for a Democratic Society rallied more than a hundred students protesting the decision to move the university campus to Columbia Point, denouncing the institution as "a 'pawn' masking the Boston Redevelopment Authority's plan to remove poor people from Columbia Point" and that "the university is planning a prestigious dormitory school with high tuition which students from low- and moderate-income families–whom the university was designed to serve–will not be able to attend."[26] In January 1974, the university moved to the current Columbia Point campus.[27] In 1977, the Massachusetts General Court formed a special legislative committee led by Amherst College President John William Ward that found (in addition to extortion payments made to Massachusetts State Senators Joseph DiCarlo and Ronald MacKenzie by McKee-Berger-Mansueto, the company contracted to supervise the construction of the campus) that the Columbia Point campus buildings were negligently constructed.[28][29][30]

In July 2006, UMass Boston Chancellor Michael F. Collins ordered the immediate and permanent closure of the parking garage underneath the main campus, causing a loss of 1,500 parking spaces and requiring the university to begin developing a 25-year plan to renew the campus the following October,[31][32] which was ultimately proposed by Chancellor J. Keith Motley and approved by the UMass Boston board of trustees in December 2007.[33] In April 2017, Chancellor Motley resigned amidst a $30 million structural operating budget deficit caused by the construction costs of the renewal plan, which required the university to begin cutting courses required for graduation during the upcoming summer and fall semesters as well as other academic spending.[34][35][36]

In 1963, when UMass System President John W. Lederle endorsed expanding the system to Boston before the state legislature, there were 12,000 freshman applications to the University of Massachusetts in Amherst with only 2,600 slots, yet the majority of the applicants lived in the Greater Boston area.[37] In the late 1960s, UMass Boston reportedly had the largest population of Vietnam War veterans than any university in the United States (many of whom had been recently discharged), and the largest population of African American students of all universities in Massachusetts.[38] As of April 2018, the UMass Boston campus remained the sole majority-minority campus in the UMass system,[39] and during the 2018–2019 academic year, UMass Boston served 650 military veterans, managed $4 million in federal G.I. benefits, and was ranked by multiple publications as being among the best universities in the United States for veteran students.[40]

Death and burial

Collins died of pneumonia in Boston, on November 23, 1995. Five days later, he was buried at St. Joseph Cemetery in West Roxbury following a funeral Mass at Boston's Holy Cross Cathedral celebrated by Cardinal Bernard Francis Law, Archbishop of Boston (1984–2002).[41] Obituaries of him published in MIT Tech Talk and by the Associated Press in The New York Times did not mention that the Boston Housing Authority actively segregated the public housing developments in the city during his tenure, nor the redlining practices of his property tax assessor's office, but the latter noted that the urban renewal policies Collins implemented in Boston were emulated across the United States.[24][42] In 2004, the same year Illinois State Senator Barack Obama gave the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in Boston, the city government commissioned a mural of Collins on the exterior of Boston City Hall adjacent to Government Center station and dedicated City Hall Plaza to him as well.[43] The caption engraved in the mural's marker does not mention the segregationist and redlining policies of the Collins mayoral administration either.

See also

- Timeline of Boston, 1960s

References

- "Collins Will Take Oath Today". The Boston Globe. January 4, 1960. p. 1. Retrieved March 17, 2018 – via pqarchiver.com.

- "'New Inaugural' in Traditional Boston Setting Today". The Boston Globe. January 1, 1968. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2018 – via pqarchiver.com.

- O'Connor, T.H. (1997). Boston Irish: A Political History. New York: Back Bay Books.

- O'Connor, Thomas H. (1995). Building a New Boston: Politics and Urban Renewal, 1950-1970. Boston: Northeastern Univ Press. p. 152. ISBN 1555532462.

- Nolan, Martin (24 November 1995). "Ex-Mayor Collins dead at 76 Fought to restore city's pride, image". The Boston Globe. p. 1.

- Lapomarda, S.J., Vincent A. (1992). The Knights of Columbus in Massachusetts (second ed.). Norwood, Massachusetts: Knights of Columbus Massachusetts State Council. p. 88.

- Girard, Christopher (7 November 2010). "Mary P. Cunniff Collins, 90, provided support to husband as Boston mayor". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- Milne, John (29 November 1995). "Collins recalled as a builder". Boston Globe. p. 29.

- Lupo, Alan (3 December 1995). "The Collins legacy: A changed Boston". The Boston Globe. p. 12.

- Tinder, Glenn (January 1961). "Reviews". The Review of Politics. 23 (1): 100. doi:10.1017/s0034670500007774.

- Lukas, J. Anthony (1986). Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 200–201. ISBN 0394746163.

- Oldman, Oliver; Aaron, Henry (1965). "Assessment-Sales Ratios Under the Boston Property Tax". National Tax Journal. 18 (1). National Tax Association. pp. 36–49. JSTOR 41791421.

- Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Campus by the Sea :: UMass Boston Historic Documents, University of Massachusetts Boston, retrieved August 5, 2017

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- "Visit of John F. Collins, Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts, 4:00PM – JFK Library". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- Lapomarda, S.J., Vincent A. (1999). "Boston, Twelve Irish-American Mayors of". In Glazier, Michael (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0268027551.

- "John F. Collins, former mayor and MIT professor, dies at 76". MIT Tech Talk. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 29 November 1995. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 121–123. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Hogarty, Richard A. (2002). Massachusetts Politics and Public Policy: Studies in Power and Leadership. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 242–246. ISBN 9781558493629.

- Silva, Cristina (July 21, 2006). "UMass closes big garage in Boston". Boston.com. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Larkin, Max; O'Keefe, Caitlin; Chakrabarti, Meghna (April 6, 2017). "J. Keith Motley, UMass Boston Chancellor, To Step Down". WBUR. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- "UMass-Boston Cuts Summer Courses As It Grapples With Deficit". WBZ-TV. April 10, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Lannan, Katie (April 24, 2017). "UMass Boston: Gov. Baker's Capital Budget Will Fund Needed Garage Repairs". WGBH. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- Rios, Simón (April 19, 2018). "UMass Boston Students, Faculty Want UMass Amherst To Drop Mount Ida Acquisition". WBUR. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- Valencia, Crystal (January 31, 2019). "UMass Boston Returns to Military Friendly List for Sixth Time". UMass Boston News. University of Massachusetts Boston. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- http://www.nndb.com/people/751/000163262/

- "John Collins, 76, Boston Mayor During City's Renewal in the 60's". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. November 24, 1995. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- "CultureNOW - Mayor John Frederick Collins: John McCormack, Boston Art Commission, City of Boston and Eduard I Browne Trust Fund". CultureNOW.org. 2004. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John F. Collins. |

- Obituary

- John F. Collins at Find a Grave

- http://www.ewtn.com/library/ISSUES/ENDIRISH.TXT

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070808222457/http://www.irishheritagetrail.com/jfcollins.htm

- NY Times Obituary

- http://www.thecrimson.com/printerfriendly.aspx?ref=492233

- http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,811423,00.html?iid=chix-del

- Boston Public Library. Collins, John F. (1919-1995) Collection

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Hynes |

Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts 1960–1968 |

Succeeded by Kevin White |