Jocelin of Glasgow

Jocelin (or Jocelyn) (died 1199) was a twelfth-century Cistercian monk and cleric who became the fourth Abbot of Melrose before becoming Bishop of Glasgow, Scotland. He was probably born in the 1130s, and in his teenage years became a monk of Melrose Abbey. He rose in the service of Abbot Waltheof, and by the time of the short abbacy of Waltheof's successor Abbot William, Jocelin had become prior. Then in 1170 Jocelin himself became abbot, a position he held for four years. Jocelin was responsible for promoting the cult of the emerging Saint Waltheof, and in this had the support of Enguerrand, Bishop of Glasgow.

Jocelin | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Glasgow | |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| See | Diocese of Glasgow |

| In office | 1174/5 – 1199 |

| Predecessor | Enguerrand |

| Successor | Hugh de Roxburgh |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 1175 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1130s Scottish Borders or Northumberland |

| Died | 17 March 1199 Melrose |

| Previous post | Abbot of Melrose |

His Glasgow connections and political profile were already well-established enough that in 1174 Jocelin succeeded Enguerrand as Glasgow's bishop. As Bishop of Glasgow, he was a royal official. In this capacity he travelled abroad on several occasions, and performed the marriage ceremony between King William the Lion and Ermengarde de Beaumont, later baptising their son, the future King Alexander II. Among other things, he has been credited by modern historians as "the founder of the burgh of Glasgow and initiator of the Glasgow fair",[1] as well as being one of the greatest literary patrons in medieval Scotland, commissioning the Life of St Waltheof, the Life of St Kentigern and the Chronicle of Melrose.

Early life

Jocelin and his family probably came from the south-east of Scotland. The names of neither his father nor his mother are known, but he had two known brothers, with the names Helia and Henry, and a cousin, also called Helia. The names suggest that his family were of French, or at least Anglo-Norman origin, rather than being a Scot or native Anglo-Saxon.[2] There are some indications that his family held land in South Lanarkshire, namely because they seem to have possessed rights in the church of Dunsyre.[3] It is unlikely that he would have thought of himself as "Scottish". For Jocelin's contemporary and fellow native of the Borders, Adam of Dryburgh, this part of Britain was still firmly regarded as terra Anglorum (the "Land of English"), although it was located inside the regnum Scottorum (the "Kingdom of the Scots").[4] This would be no obstacle to Jocelin, however. His Anglo-French cultural background was in fact probably necessary for the patronage of the King of Scots. As Walter of Coventry wrote of King William's era, "the modern kings of Scotland count themselves as Frenchmen, in race, manners, language and culture; they keep only Frenchmen in their household and following, and have reduced the Scots to utter servitude".[5]

Like that of almost every character from this period, Jocelin's year of birth is unknown to modern historians. It is known that he entered as a novice monk in Melrose Abbey during the abbacy of Waltheof (ab. 1148–1159), and from documentary evidence it seems likely that Jocelin entered Melrose about 50 years before his death in 1199. As the rules of the Cistercian order prevented entry as a novice before the age of 15, it is likely that he was born around the year 1134.[6] Little is known about Jocelin's early life or his early career as a Melrose monk. He obviously successfully completed his one-year noviciate, the year in which a prospective monk was introduced to monasticism and judged fit or unfit for admittance. We know that Abbot Waltheof (Waldef) thought highly of him and granted him many responsibilities.[2] After the death of Abbot Waltheof, his successor, Abbot William, refused to encourage the rumours which had quickly been spreading about Waltheof's saintliness. Abbot William attempted to silence such rumours, and shelter his monks from the intrusiveness of would-be pilgrims. However, William was unable to get the better of Waltheof's emerging cult, and his actions had alienated him from the brethren. As a result, William resigned the abbacy in April 1170.[7] Jocelin was by this stage the Prior of Melrose, that is, the second in command at the monastery, and thus William's most likely replacement.

Abbot of Melrose

So it was that Prior Jocelin became abbot on 22 April 1170.[8] Jocelin embraced the cult without hesitation. Under the year of his accession, it was reported in the Chronicle of Melrose that:

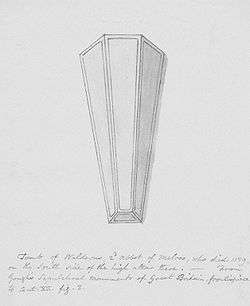

The tomb of our pious father, sir Waltheof, the second abbot of Melrose, was opened by Enguerrand, of good memory, the bishop of Glasgow, and by four abbots called in for this purpose; and his body was found entire, and his vestments intact, in the twelfth year from his death, on the eleventh day before the Kalends of June [22 May]. And after the holy celebration of mass, the same bishop, and the abbots whose number we have mentioned above, placed over the remains of his most holy body a new stone of polished marble. And there was great gladness; those who were present exclaiming together, and saying that truly this was a man of God ...[9]

Promoting saints was something Jocelin would repeat at Glasgow, where he "transferred his enthusiasm to St Kentigern"[10] and commissioned a hagiography of that saint, the saint most venerated by the Celts of the diocese of Glasgow. It is no coincidence that Jocelin of Furness, the man who wrote the Life of St. Waltheof, was the same man later commissioned to write the Life of St. Kentigern.

This kind of literary patronage started while Jocelin was abbot of Melrose. Archie Duncan has shown that it was probably Jocelin who first commissioned the writing of the Chronicle of Melrose. Duncan argued that Jocelin commissioned the entries dealing with the period between 731 and 1170, putting the writing in the hands of a monk named Reinald (who later became Bishop of Ross).[11] This chronicle is one of the few extant chronicles from "Scotland" in this period. G. W. S. Barrow, writing before Duncan advanced these arguments, noted that down to the end of King William's reign "the chronicle of Melrose Abbey ... represents a strongly 'Anglo-Norman' as opposed to a native Scottish point of view".[12] It is thus possible that this anti-Scottish world-view reflected that of Jocelin's, at least before he left the abbey.

After his election to the prestigious bishopric of Glasgow in 1174, Jocelin would continue exerting influence on his home monastery. Jocelin brought one of his monks from the abbey, a man called Michael, who acted as Jocelin's chaplain while Bishop of Glasgow.[13] He did not resign his position as abbot until after his consecration in 1175. Jocelin consecrated his successors as abbot, and continued to spend a great deal of time there. Moreover, he used his position as bishop to offer the monastery patronage and protection.[14]

Bishop of Glasgow

After the death of his friend Bishop Enguerrand, Jocelin was elevated to the bishopric of Glasgow. He was elected on 23 May 1174. The election, like many other Scottish episcopal elections of the period, was done in the presence of the king, William the Lion, at Perth, near Scone, the chief residence of Scotland's kings.[15] The election was probably done by compromissarii, meaning that the general chapter of the bishopric of Glasgow had selected a small group to which they delegated the power of election.[16] Pope Alexander III was later told that Jocelin was elected by the dean and chapter of the see.[17] The Chronicle of Melrose states that he was elected "by demand of the clergy, and of the people; and with the consent of the king himself",[18] perhaps indicating that the decision had already been made by the Glasgow clergy before the formal election at Perth. The election was certainly an achievement. Cistercian bishops were rare in Great Britain, and Jocelin was only the second Cistercian to ascend a Scottish bishopric.[17] Jocelin was required to go to France to obtain permission from the General Chapter of the Cistercian order at Cîteaux to resign the abbacy. Pope Alexander III had already sanctioned his consecration, and gave permission for the consecration to occur without forcing Jocelin to travel to Rome. Conveniently, it was at Cistercian house of Clairvaux that, sometime before 15 March 1175, Jocelin was consecrated by the Papal legate Eskil, Archbishop of Lund and Primate of Denmark.[19] Jocelin had returned to the Kingdom of Scotland by 10 April, and it is known that on 23 May he had consecrated a monk named Laurence as his successor at Melrose.[20]

He was soon faced with a political challenge to the independence of his church. The challenge came from the English church, and was not new, but had lain dormant for some decades. The reason it was awakened was that in the summer of 1174 King William had invaded northern England, and on 13 July, having been caught underprotected during a siege at Alnwick, was captured and taken into English custody.[21] The capture was disastrous for the king, leading to a revolt by Gilla Brigte, Lord of Galloway, and to many of William's discontented subjects "ruthlessly" slaying "their English and French neighbours" and perpetrating a "most wretched and widespread persecution of the English both in Scotland and Galloway", that is, of the English and French-speaking settlers William and his predecessors had planted around the castles and towns of his Gaelic-speaking territories in order to increase royal authority.[22] Worse still, and more significantly for Jocelin, in the following year King Henry II of England forced William to sign the Treaty of Falaise, a treaty which made William Henry's vassal specifically for Scotland and sanctioned the subordination of the kingdom's bishoprics to the English church.[23]

Jocelin did not, in the end, submit either to the Archbishop of York or even the Archbishop of Canterbury and managed to obtain a Papal Bull which declared the see of Glasgow to be a "special daughter" of the Roman Patriarchate.[24] Jocelin, moreover, does not seem to have been interested in the independence of the other "Scottish" sees, but merely to maintain his own episcopal independence, i.e. that of the bishopric of Glasgow. On 10 August 1175, along with many other Scottish-based magnates and prelates, Jocelin was at Henry's court giving his obedience to the king as stipulated in the treaty. Jocelin again appeared at King Henry's court in January 1176. This time church matters were on the agenda. When the Archbishop of York confronted Jocelin over the subordination of the bishopric of Glasgow to the archbishopric of York, Jocelin refused to acknowledge this part of the treaty, and presented him with the Papal Bull declaring Glasgow to be a "special daughter".[25]

This Bull was confirmed by Pope Alexander's successor Pope Lucius III.[26] Jocelin had obtained this confirmation while at Rome in late 1181 and early 1182. He had been sent there by King William, along with abbots of Melrose, Dunfermline and Kelso and the prior of Inchcolm, in order to appeal to the Pope regarding his stance in a struggle over the Bishopric of St Andrews and the sentence of excommunication and interdict the Pope had placed over the king and kingdom. The dispute concerned the election to the bishopric of John the Scot, which had been opposed by the king, who organised the election of his own candidate, Hugh. The mission was successful. The Pope lifted the interdict, absolved the king and appointed two legates to investigate the issue of the St Andrews succession. The Pope even sent the king a Golden Rose, an item usually given to the Prefect of Rome.[27] The issue of the succession, however, did not go away. In 1186, Jocelin, along with the abbots of Melrose, Dunfermline and Newbattle, excommunicated Hugh on the instructions of Pope Lucius.[28] Hugh travelled to Rome in 1188, and obtained absolution, but he died of the pestilence in that city a few days later, thus allowing the issue to be resolved.[29]

It is certainly obvious that Jocelin was one of the most respected figures in the kingdom. In this era, the Pope appointed Jocelin Judge-delegate (of the Papacy) more times than any other cleric in the kingdom.[30] As a bishop and an ex-abbot, various bishoprics and monasteries called him in to mediate disputes, as evidenced by his frequent appearance as a witness in dispute settlements, such as the dispute between Arbroath Abbey and the Bishopric of St Andrews, and a dispute between Jedburgh Abbey and Dryburgh Abbey.[31] Jocelin had the respect of the secular elite too. He witnessed 24 royal charters[28] and 40 non-royal charters, including charters issued by David, Earl of Huntingdon (the brother of King William), Donnchadh, Earl of Carrick, and Alan Fitzwalter, High Steward of Scotland.[30] Jocelin had been with King William when he visited the English court in 1186, and again accompanied the king to England when the king travelled to Woodstock near Oxford to marry Ermengarde de Beaumont on 5 September 1186. The marriage was blessed by Bishop Jocelin in their chamber, and it was to Jocelin's escort that King William entrusted her for the journey to Scotland. When a son was born to William and Ermengarde, the future King Alexander II, it was Jocelin who performed the baptism.[32] In April 1194, Jocelin again travelled to England in King William's company when William was visiting King Richard I.[33] Jocelin's intimacy with the king would be the key to earning his patronage, thus making possible the legacy that Jocelin would leave to Glasgow.

Legacy and death

His years at Glasgow left a mark on history that can be compared favourably with any previous or future bishop. Jocelin commissioned his namesake Jocelin of Furness, the same man who had written the Life of St. Waltheof, to write a Life of St. Kentigern, a task all the more necessary because, after 1159, the Papacy claimed the right to canonise saints.[34] Kentigern, or Mungo as he is popularly known,[35] was the saint traditionally associated with the see of Glasgow, and his status therefore reflected on Glasgow as a church and cult-centre. There had already been a cathedral at Glasgow before Jocelin's episcopate. The idea that the ecclesiastical establishment before Jocelin was simply a small church with a larger Gaelic or British monastic establishment has been discredited by scholars.[36] Jocelin did, though, expand the cathedral significantly. As the Chronicle of Melrose reports for 1181, Jocelin "gloriously enlarged the church of St Kentigern".[37] However, more work was created for the builders when, sometime between the years 1189 and 1195, there was a fire at the cathedral. Jocelin thus had to commission another rebuilding effort.[38] The new cathedral was dedicated, according to the Chronicle of Melrose, on 6 July 1197.[39] It was built in the Romanesque manner, and although little survives of it today, it is thought to have been influenced by the cathedral of Lund, the archbishop of which had consecrated Jocelin as bishop.[40]

However, he left a still greater legacy to the city of Glasgow. At some point between the years 1175 and 1178, Jocelin obtained from King William a grant of burghal status for the settlement of Glasgow, with a market every Thursday. The grant of a market was the first ever official grant of a weekly market to a burgh. Moreover, between 1189 and 1195, King William granted the burgh an annual fair, a fair still in existence today, increasing Glasgow's status as an important settlement. As well as new revenues for the bishop, the rights entailed by Glasgow's new burghal status and market privileges brought new people to the settlement, one of the first of whom was one Ranulf de Haddington, a former burghess of Haddington. The new settlement was laid out (probably under the influence of the burgh of Haddington) around Glasgow Cross, down the hill from the cathedral and old fort of Glasgow, but above the flood level of the River Clyde.[41]

When Jocelin died, he was back at Melrose Abbey, where his career had begun. He may have retired to Melrose knowing his death was near.[42] Jocelin certainly did die at Melrose, passing away on St Patrick's Day (17 March) 1199. He was buried in the monks' choir of Melrose Abbey Church.[43] Hugh de Roxburgh, Chancellor of Scotland, was elected as Jocelin's replacement. The Chronicle of Melrose has only a short obituary.[44]

Notes

- For this view and quote, see Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin, abbot of Melrose), and bishop of Glasgow)", in The Innes Review, vol. 54, no. 1 (Spring, 2003), p. 1.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 2.

- A. A. M. Duncan, "Jocelin (d. 1199)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 29 Nov 2006.

- The full Latin description is "in terra Anglorum et in regno Scottorum", Adam of Dryburgh, De tripartito tabernaculo, II. 210, tr. Keith J. Stringer, "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", in Edward J. Cowan & R. Andrew McDonald (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, (East Lothian, 2000), p. 133.

- W. Stubbs (ed.), Memoriale Fratris Walteri de Coventria, (Rolls Series, no. 58), ii. 206; trans. G. W. S. Barrow, "The Reign of William the Lion", in G.W.S. Barrow (ed.), Scotland and its Neighbours in the Middle Ages, (Edinburgh, 1972), p. 72.

- For this argument, and the references to the relevant primary material, see Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", pp. 1–2.

- For the account of Abbot William and the cult of Waltheof, see Richard Fawcett, & Richard Oram, Melrose Abbey, (Stroud, 2004), pp. 23–24.

- For date of accession, see John Dowden, The Bishops of Scotland, ed. J. Maitland Thomson, (Glasgow, 1912), p. 298.

- Chronicle of Melrose, s.a. 1171, trans. A.O. Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500–1286, 2 Vols, (Edinburgh, 1922), vol. ii, pp. 274–275; translation slightly modernised in Fawcett & Oram, Melrose Abbey, p. 23; this entry was written after the year for which it was written, sometime after the death on 22 February 1174 of Enguerrand, Bishop of Glasgow.

- A. A. M. Duncan, "Sources and Uses of the Chronicle of Melrose,", in Simon Taylor (ed.), Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297, (Dublin, 2000), p. 150.

- Ibid., pp. 149–150.

- G. W. S. Barrow, The Acts of William I, Regesta Regum Scottorum, vol. ii, (Edinburgh, 1971), p. 7.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 16.

- Fawcett & Oram, Melrose Abbey, pp. 23–24.

- John Dowden, Bishops of Scotland, p. 298.

- A.A.M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, (Edinburgh, 1975), p. 277, n. 38.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 4.

- Chronicle of Melrose, s.a. 1174, trans. Alan Orr Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, vol. ii, p. 289.

- Chronicle of Melrose, s.a. 1175, for which see A.O.Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, vol. ii, p. 296; see also John Dowden, Bishops of Scotland, p. 298, & Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", pp. 5–6.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 6.

- W. W. Scott, "William I [William the Lion] (c.1142–1214)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 , accessed 1 Dec 2006.

- This is reported in a 13th-century Scottish chronicle called the Gesta Annalia I; for text, see William F. Skene, Johnnis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum, (Edinburgh, 1871), pp. 263–4; for translation, see Felix J. H. Skene, John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, (Edinburgh, 1872), p. 259; for 13th-century date of text, see Dauvit Broun, "A New Look at Gesta Annalia attributed to John of Fordun", in Barbara Crawford (ed.), Church, Chronicle and Learning in Medieval and Early Renaissance Scotland, (Edinburgh, 1999), pp. 9–30. These events are also reported in some detail by William of Newburgh, Historia Rerum Anglicarum, in R. Howlett (ed.) Chronicles of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I, (Rolls Series, no. 82), vol. i, pp 186–187; for this account, and other English accounts, see also Alan Orr, Anderson, Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers: AD 500–1286, (London, 1908), republished, Marjorie Anderson (ed.) (Stamford, 1991), pp. 255–258; the Galwegian revolt is subjected to some analysis by Richard Oram, The Lordship of Galloway, (Edinburgh, 2000), pp. 95–96.

- All of the details in this paragraph so far can G. W. S. Barrow, The Acts of William I, Regesta Regum Scottorum, vol. ii, (Edinburgh, 1971), pp. 7–8.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", pp. 6–7.

- A. A. M. Duncan, Jocelin (d. 1199)".

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", pp. 8–9.

- loc. cit.; A.A.M. Duncan, Making of the Kingdom, pp. 272–273.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 9.

- John Dowden, Bishops of Scotland, p. 10.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 19.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 20.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 10; D.D.R. Owen, The Reign of William the Lion: Kingship and Culture,, (East Linton, 1997), pp. 71–72.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 10.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", pp. 12–13.

- This is a modern anglicisation of his Gaelic nickname.

- See, for instance, G.W.S. Barrow, "David I and Glasgow", in G.W.S. Barrow (ed.), The Kingdom of the Scots, 2nd Edition, (Edinburgh, 2003), p. 210.

- Chronicle of Melrose, s.a. 1181, for which see Alan Orr Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, vol. ii, p. 304.

- This fire is mentioned in a royal charter, which can only be dated to the period between 1189 and 1195, hence the dating of the fire; Regesta Regum Scottorum, ii, no. 316; see also Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 13.

- Chronicle of Melrose, s.a. 1197, for which see Alan Orr Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, vol. ii, p.

- Norman F. Shead, "Jocelin", p. 14.

- For the information in this paragraph, see Ibid., pp. 11–12.

- Richard Fawcett & Richard Oram, Melrose Abbey, p. 25.

- John Dowden, Bishops of Scotland, p. 299.

- See A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, vol. ii, p. 351.

References

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500–1286, 2 Vols, (Edinburgh, 1922), vol. ii

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers: AD 500–1286, (London, 1908), republished, Marjorie Anderson (ed.) (Stamford, 1991)

- Barrow, G. W. S. (ed.), The Acts of William I, Regesta Regum Scottorum, vol. ii, (Edinburgh, 1971)

- Barrow, G. W. S., "David I and Glasgow", in G.W.S. Barrow (ed.), The Kingdom of the Scots, 2nd Edition, (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 203–213

- Barrow, G.W.S., "The Reign of William the Lion", in G.W.S. Barrow (ed.), Scotland and its Neighbours in the Middle Ages, (Edinburgh, 1972), pp. 67–89

- Broun, Dauvit, "A New Look at Gesta Annalia attributed to John of Fordun", in Barbara Crawford (ed.), Church, Chronicle and Learning in Medieval and Early Renaissance Scotland, (Edinburgh, 1999), pp. 9–30

- Dowden, John, The Bishops of Scotland, ed. J. Maitland Thomson, (Glasgow, 1912)

- Duncan, A. A. M., "Jocelin (d. 1199)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 29 Nov 2006

- Duncan, A. A. M., Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, (Edinburgh, 1975)

- Duncan, A. A. M., "Sources and Uses of the Chronicle of Melrose,", in Simon Taylor (ed.), Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297, (Dublin, 2000)

- Fawcett, Richard, & Oram, Richard, Melrose Abbey, (Stroud, 2004)

- Howlett R. (ed.), Chronicles of Stephen, Henry II and Richard I, (Rolls Series, no. 82)

- Oram, Richard, The Lordship of Galloway, (Edinburgh, 2000)

- Owen, D. D. R., The Reign of William the Lion: Kingship and Culture,, (East Linton, 1997)

- Scott, W. W., "William I [William the Lion] (c.1142–1214)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 , accessed 1 Dec 2006

- Shead, Norman F., "Glasgow: An Ecclesiastical Burgh", in M. Lynch, M. Spearman & G. Stell (eds.), The Scottish Medieval Town, (Edinburgh, 1988), pp. 116–132

- Shead, Norman F., "Jocelin, abbot of Melrose), and bishop of Glasgow)", in The Innes Review, vol. 54, no. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 1–22

- Skene, Felix J. H., John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, (Edinburgh, 1872)

- Skene, William F., Johnnis de Fordun: Chronica Gentis Scotorum, (Edinburgh, 1871)

- Stringer, Keith J., "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", in Edward J. Cowan & R. Andrew McDonald (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, (East Lothian, 2000), pp. 127–165

Further reading

- Driscoll, Stephen T., Excavations at Glasgow Cathedral, Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 18, (Leeds, 2002)

- Driscoll, Stephen T., "Excavations in Glasgow Cathedral: A preliminary report on the archaeological discoveries made in 1992–3", in Glasgow Archaeological Journal, 17, (1992), pp. 63–76

- Duncan, A.A.M., "St Kentigern in Glasgow Cathedral in the twelfth century", in Richard Fawcett (ed.), Medieval Art and Architecture in the Diocese of Glasgow, (Leeds, 1998)

- Forbes, A.P. (ed.), Lives of St Ninian and St Kentigern, (Edinburgh, 1874)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jocelin (Bishop of Glasgow). |

See also

- Christianity in Medieval Scotland

- Roman Catholicism in Great Britain

- Scotland in the High Middle Ages

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William |

Abbot of Melrose 1170–1174 |

Succeeded by Laurence |

| Preceded by Enguerrand |

Bishop of Glasgow 1174/5 – 1199 |

Succeeded by Hugh de Roxburgh |