Jewish Autonomism

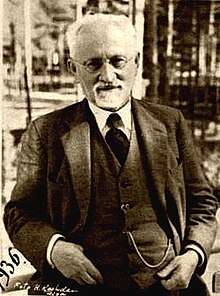

Jewish Autonomism, not connected to the contemporary political movement autonomism, was a non-Zionist political movement and ideology that emerged in Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century. One of its first and major proponents was the historian and activist Simon Dubnow. Jewish Autonomism is often referred to as "Dubnovism" or "folkism".

The Autonomists believed that the future survival of the Jews as a nation depends on their spiritual and cultural strength, in developing "spiritual nationhood" and in viability of Jewish diaspora as long as Jewish communities maintain self-rule and rejected assimilation. Autonomists often stressed the vitality of modern Yiddish culture. Various concepts of the Autonomism were adopted in the platforms of the Folkspartei, the Sejmists and socialist Jewish parties such as the Bund.

The movement's beliefs were similar to those of the Austro-Marxists who advocated national personal autonomy within the multinational Austro-Hungarian empire and cultural pluralists in America such as Randolph Bourne and Horace Kallen.

History

Though Simon Dubnow was key in proliferating Autonomism's popularity, his ideas were not completely novel. In 1894, Jakob Kohn, a board member of the National Jewish Party of Austria published Assimilation, Antisemitismus und Nationaljudentum, a philosophical work detailing his party's perspective. Kohn argued that Jews shared not only a religion, but were connected by a long, deep-rooted ethnic history of centuries of discrimination, attempts at assimilation and exile. To Kohn, the Jews were a nation. Similar to Dubnow, Kohn called for the establishment of a Jewish organization to represent Jewish interests within the state's policies. Again, Similar to Dubnow, Kohn denounced assimilation, claiming that it worked against the establishment of a Jewish nation.[1]

The origins of Autonomism and Dubnow's ideas remain unclear. Notable philosophical thinkers from Eastern and Western Europe including Ernest Renan, John Stuart Mill, Herbert Spencer and Auguste Compte are cited to have influenced Dubnow's ideas. Ideas from Vladimir Solovyov, Dmitry Pisarev, Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Konstantin Aksakov concerning the Russian people's distinct spiritual heritage may have brought rise to Dubnow's own ideas on the Jews shared heritage. In his memoirs, Dubnow himself refers to some of these thinkers as major influences. In addition, Dubnov had been immersed in histiographical study of Russian Jewry, its institutions and spiritual movements. This research led Dubnov to question the legitimacy of the Russians' monopoly of political power and fueled his own demands for Jewish political representation.[1]

With the Holocaust and the murder of Simon Dubnow in the 1941 Rumbula massacre, the foundation for Jewish Autonomism came to end and has no practical impact in today's politics.[2]

Autonomism vs. Zionism

Ideological differences

Whereas Zionism advocates for the establishment of an entirely separate Jewish state, Autonomism advocates for the sovereignty of the Jews without a division from the governing state. This allows Jews to simultaneously identify with Jewish nationalism and loyalty to their own state. In contrast to many other ideologies, Dubnow believed that as a nation the Jews had transformed for the better. To Dubnow, the Jews had transformed from a nation connected by a territory to a nation connected by a spirituality and heritage.

Some groups blended Autonomism with Zionism as they favored Jewish self-rule in the diaspora until diaspora Jews make Aliyah to their national homeland in Zion.[3]

Historical conflicts

In the early 1900s, the Folkspartei, a political party advocating for Jewish Autonomism strove for good relations with other Jewish parties, including the Zionists. An attempt was made to establish a Jewish National Club, an inter-party organization to coordinate collaboration between the two parties. However, this failed when the Folkists objected to accepting an unequal number of committee representatives.[3]

References

- Homelands and diasporas : Greeks, Jews and their migrations. Rozen, Minna. London: I.B. Tauris. 2008. ISBN 9781441615978. OCLC 503446276.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli conflict : a political, social, and military history. Tucker, Spencer, 1937, Roberts, Priscilla Mary, 1955. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. 2008. ISBN 9781851098415. OCLC 212627327.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Weiser, Keith Ian (2012). Jewish people, Yiddish nation : Noah Prylucki and the Folkists in Poland. Canadian Electronic Library. Toronto [Ont.]: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442662094. OCLC 772396207.

External links

- Autonomism at Jewish Virtual Library