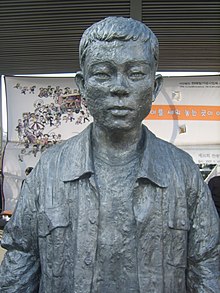

Jeon Tae-il

Jeon Tae-il (August 26, 1948 – November 13, 1970) was a South Korean sewing worker and workers' rights activist who committed suicide by burning himself to death at the age of 22 in protest at the poor working conditions of South Korean factories.[1] His death brought attention to the substandard labor conditions and helped the formation of labor union movement in South Korea.[2]

Jeon Tae-il | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 28, 1948 Daegu, Gyeongsang Province, South Korea |

| Died | November 13, 1970 (aged 22) Dongdaemun District, Seoul, South Korea |

| Korean name | |

| Hunminjeongeum | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Jeon Tae-il |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chŏn T'ae-il |

Early life

Jeon Tae-il was born on September 28, 1948 to the son of Jeon Sang-soo, a poor worker in Namsan-dong, Daegu, and his wife, Lee So-sun. At one time, his father, Jeon Sang-soo, also did domestic water industry, but failed repeatedly. His mother, Lee So-sun's father, was killed by a Japanese police officer on charges of joining the anti-Japanese independence movement. In 1954, all family members came to Seoul. The family was homeless under the Yeomcheon Bridge near Seoul Station. His mother begged in Manni-dong. Jeon Tae-il father, who was doing sewing work, got a job, so family could live at monthly rent room.[3]

However, the family went back to Daegu in 1960. He could not finished elementary school. After that, he had an underprivileged childhood with little formal education and a variety of peddling on the street to live. In March 1963, he entered Cheong-ok High School in Daegu, but due to family circumstances, he dropped out of school during the first grade in December of that year. In the winter of 1963, his father, Jeon Sang-soo, forced his son to drop out of school. His father forced him to leave school and do only sewing work at home. He was frustrated that he couldn't go to school, and he ran away from home and returned home in three days. His father said that he had to earn money to study, and kicked him and beat him, forcing him to leave school.[3]

Youth

He learned to sew from his father, but he ran away from home again with his younger brother in 1964 and went to Seoul. He was peddling at Dongdaemun Market, and delivered newspaper, did shoe polishing, etc. He was employed as an assistant at the Seoul Peace Market's clothing store by the sewing skills that he learned from his father. He worked for 14 hours and was paid 50 won per day for a cup of tea. When he turned 17, he became a Sida (which means chore) at Sam-il sa in the peace market, and soon became a tailor .[3]

Worker's human rights movement

A tailor himself, Jeon witnessed the horrendous working conditions in the Seoul Peace Market (서울평화시장; Seoul Pyeonghwa Sijang). Such conditions included rampant tuberculosis due to poor ventilation (or the lack thereof) in the sweatshops, and the enforced injections of amphetamines to keep sleep-deprived workers awake and to work them overtime without proper compensation.

In 1968 he noticed that there was a work standard law that is law to protect workers' human rights.[4] After that he bought manual of work standard law and studied by that. While studying the contents of the law, he was angry at the reality that even the minimum working conditions prescribed by law were not observed. In June 1969, he founded the Fool's Association(바보회), the first labor movement organization in the peace market. Fool's Association(바보회) is the name of Jeon Tae-il's reflection as a worker. Rather than struggling to argue that workers also have human rights, it means that they were fool who conforms to an exploitative working environment. He informed the workers of the peace market the contents of the Labor Standards Act and unfairness of their current working conditions. Also he surveyed the current status of work through a questionnaire.[4]

Also, protesting against such was, by association, protesting against the oppressive rule of Park Chung-hee, South Korea's then-dictator president. Although Jeon succeeded in briefly creating awareness, he soon met with resistance from the government, which almost entirely ignored labor regulations and frequently sided with the employers who were accused of exploitation. Scornful Labor Department officials told Jeon and his colleagues they were unpatriotic for complaining, and employers simply cracked down harder.

Death

Ultimately, in order to force attention onto the issue he set himself on fire and ran through the streets of downtown Seoul shouting slogans such as, "We workers are human beings, too!" "Guarantee the Three Basic Labor Rights," and "Do not let my death be in vain".[2] He was transported to a nearby hospital but did not survive the wounds suffered from burning himself.

Jeon Tae-il received emergency treatment but his body was not able to stretch out because it was too hard. Jeon Tae-il left a testament to his mother, Lee So-sun, "Mother, please do something I could not do." [5] Jeon Tae-il's mother took off her apron to cover her shivering son and went to the doctor. Doctors said to her that injection that price is 15,000 won can relieve burns first. But she couldn't pay that. At around 4 pm, he was taken by ambulance and sent back to the emergency room at St. Mary's Hospital in Seoul, but died in the emergency room at St. Mary's Hospital at 10 pm on November 13. At St. Mary's Hospital, Jeon Tae-il was left in the emergency room for some time before moving to the hospital. The doctor diagnosed that there is no hope for recovery.[4]

After death

His death mobilized and motivated workers to take up the struggle, and this eventually led to the creation of labor unions that were gradually able to secure workers' rights. Also, his death became a catalyst for uniting many university students, some religious officials, and the newspaper media, which continuously silenced their support for the cause of the workers. [6]

The biographic film A Single Spark details Jeon's struggle. A bestselling biography of him was published in 2001.[4]

The 2012 Documentary film Mother tells the story of Jeon's mother, Lee So-Sun. In April 2012, his younger sister, Jeon Soon-ok, was elected a member of National Assembly of South Korea, as a member of Democratic United Party(constituency: proportional representation)

Since the beginning of the first anniversary ceremony of Jeon Tae-il, a Christian youth in 1972, the title has changed to the commemoration ceremony of the labor activist Jeon Tae-il in the 1980s. His mother, Lee So-sun, was called the mother of workers by devoting herself to supporting the Cheonggyecheon union and supporting the labor movement until her death.[7] In 1984, the Jeon Tae-il Commemorative Project was organized in Seoul, centered around labor activists[8] and in 1985, the Jeon Tae-il Memorial Hall was opened.[9] Afterwards, the Jeon Tae-il Foundation was organized to start awarding the Jeon Tae-il Literary Award and the Jeon Tae-il Labor Award. After the June Struggle in 1987, labor groups gathered and held workers' meetings from July to August of that year. On July 15, the '87 Declaration of the Liberation of the Working Class' was held in reference to his commentary. In November 1988, a national workers' meeting was held in Seoul to commemorate Jeon Tae-il's self-immolation and is held every November. In 2001, Jeon Tae-il was approved as a member of the democratization movement.[10] On September 19, 1996, Jeon Tae-il Street was created in Euljiro 6-ga, Jung-gu, Seoul. In commemoration of this, a memorial performance was held in front of a painting containing the image of Jeon Tae-il's self-immolation. In this Jeon Tae-il Street','Jeon Tae-il Street Cultural Festival' is held to commemorate Jeon Tae-il.[11]

The labor world

After his suicide, the Cloth Workers' Union was formed in the peace market, and other factories also could get the opportunity to form a union. The case that Jeon Tae-il died while shouting that workers are people, not machines, greatly influenced the working world and became the starting point of a full-fledged labor movement. Workers who had suffered from the exploitation and termination of the company but did not intend to struggle, awakened after Jeon Tae-il's death.[6]

Different reactions of the peace market

The boss of a company in the peace market said he was worried about being investigated because of Jeon Tae-il's death. The boss said later, "If Jeon Tae-il worked at our factory, it would be a really big problem.". Some workers were cynical about his death. Some workers even said that "Jeon's death can't make any change of worker's right.". At that time, some workers who did not receive proper education did not care about the Jeon's death.[3]

Social reaction

His death, which accused the lives of workers who were not respected for basic human rights, had a great social impact. On November 16, more than 100 law students at Seoul National University claimed to receive his body and to perform a funeral and more than 400 students engaged indefinite fasting protests. On November 20, students from Seoul National University, Sungkyunkwan University, and Ewha Womans University and other student activists from Seoul gathered to hold a memorial ceremony for Jeon Tae-il at Seoul National University Law School and held a demonstration. Korea University and Yonsei University students also participated in the rally. After the protests, Seoul National University issued an indefinite suspension of business, but Seoul National University students continued to engage in vigils.[12]

On the 22nd, about 40 college students at Sae moon-an Church held a fasting prayer for the Atonement saying that society is responsible for the death of Jeon Tae-il and that they are also conspirators. On the 23rd, Christianity held a memorial service in collaboration with Protestantism and Catholicism.[4]

At that time, Kim Dae-jung, a candidate for the president of the New Democratic Party, also announced at the press conference on January 23, 1971, "Implementation of the spirit of Jeon Tae-il" as a pledge.[4] Since then, the New Democratic Party has developed a policy of favor for the labor movement and protesters often took refuge in the New People's Party, avoiding oppression by the police and government.[4]

References

- 류재택 [Ryu Jae-taek] (2005), 전태일, Doosan Encyclopedia, retrieved 2010-10-04

- Lee, Namhee (2009). The Making of Minjung. Ithaca, United States: Cornell University Press. pp. 218. ISBN 0-8014-4566-3.

- Ahn, Soo Chan. "한겨레 전태일의 시간·공간·생각 (The Hankyoreh article Jeon Tae-il's Time,Space and his Will)". h21.hani.co.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- 조영래 [Cho Yŏng-nae] (2001), 《전태일평전(A Single Spark)》, 돌베개 [Tol Pegae], ISBN 978-89-7199-134-3, OCLC 49858116

- Ahn, Hyo Jin (2014-10-31). "Story of Mothers' Child Rearing Community, "Love of Children"". Journal of Korean Child Care and Education. 10 (5): 299–319. doi:10.14698/jkcce.2014.10.5.299. ISSN 1738-9496.

- 지 Chi, 명관 Myeong Gwan (1996). 한국 을 움직인 현대사 61장면 (61 scenes of modern history of Korea). 다섯 수레 Tasŏt Sure. p. 61. ISBN 89-7478-062-3. OCLC 36995099.

- "이소선 어머니와 노동운동 (Mother Lee So-sun and Labor movement)". 한국노동사회연구소(Korean Labor Institute) klsi.org (in Korean). 2013-06-06. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "Beautiful Youth Jeon Tae-il Foundation From Foundation Introduction". www.chuntaeil.org. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "[전태일기념관] 기념관 안내 Jeon Tae-il Memorial Hall Guide of Memorial Hall". www.taeil.org (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- 지면보기, 입력 2001 01 22 00:00 | 종합 23면 (2001-01-22). "분신 전태일 민주화 운동 공식 인정 (Former recognition of the contributor to the Jeon Tae Il democratization movement)". 중앙일보 (JoongAng Ilbo) (in Korean). Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "한겨레 '전태일 거리'선포 (The Hankyoreh Declaration of Jeon Tae-il Street)". NAVER Newslibrary. 1996-09-20. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- Lee, Gwang-Il (1998). "《당대비평》(Contemporary criticism)". 당대. 4: 279 – via Google books.

External links

- (in Korean) 전태일재단

- (in Korean) 전태일 "어느 청년 재단사의 꿈"