James Basset

James Basset (1526–1558) was a gentleman from an ancient Devonshire family who became a servant of Stephen Gardiner (c. 1483–1555), Bishop of Winchester, by whom he was nominated MP for Taunton in 1553, for Downton in 1554, both episcopal boroughs.[1] He also served thrice as MP for Devon in 1554, 1555, and 1558.[2] He was a strong adherent to the Catholic faith during the Reformation started by King Henry VIII. After the death of King Edward VI in 1553 and the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary I, he became a courtier to that queen as a gentleman of the Privy Chamber and received many favours from both herself and her consort Philip II of Spain.

Origins

James Basset was the third son[3] and youngest child[4] of Sir John Basset (1462–1528), KB, of Tehidy in Cornwall and Umberleigh in Devon (Sheriff of Cornwall in 1497, 1517 and 1522 and Sheriff of Devon in 1524) by his second wife Honor Grenville (died 1566), a daughter of Sir Thomas Grenville (died 1513) of Stowe in the parish of Kilkhampton, Cornwall, and lord of the manor of Bideford in North Devon, Sheriff of Cornwall in 1481 and in 1486.[5] Cousin of Sir Richard Grenville, Honor Grenville's nephew.

His sister Anne Bassett was allegedly considered as a wife of King Henry VIII and may have been one of the Mistresses of Henry VIII.[6]

Childhood

When James was two years old in 1528 his father died and shortly thereafter his mother remarried to Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle, who was an illegitimate son of King Edward IV, a half-brother of Queen Elizabeth of York, an uncle of King Henry VIII, and who was appointed by the latter to serve (1533–40) as Lord Deputy of Calais.[7]

Education

James briefly moved to Calais with his mother and stepfather[8] but in 1534, aged eight, was being educated for a clerical career, as befitted a younger son of the gentry, at Reading Abbey. When his mother determined in December 1534 to send James to school in Paris, she turned for help in supervising his care to "John Bekinsau, Thomas Rainolde, and Walter Bucler ... Oxford scholars ... drawn to Paris by the reputation of its great University".[9] He was soon back on the Continent and in August 1535 was at Calvy College in Paris. Between 1536 and 1538 he received private tuition in Paris and St Omer, with a period spent at the College of Navarre in Paris in 1537-8.[10] Sixteen of his letters[11] to his mother survive in the Lisle Papers, held at the UK National Archives.

Career

Reign of Henry VIII

In 1538 he entered the household of Stephen Gardiner (c. 1483–1555), Bishop of Winchester, whom he served firstly as a gentleman of the household, remaining in his faithful service for thirteen years.[12]

Reign of Edward VI

In 1547 at the start of the reign of King Edward VI (1547–1553) Gardiner was imprisoned first in the Fleet and remained in the Tower of London for six years until released on the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary I (1553–1558). During his imprisonment Basset remained loyal to his master and before his trial appealed to the Lord Protector Somerset[13] and later petitioned parliament[14] for his release. At the bishop's trial in 1551 Basset was shown to have been one of his gentlemen waiters and served as one of his proctors, and gave evidence.[15] He was himself imprisoned briefly and released from the Tower of London on 1 October 1551.[16] John Foxe (died 1587) the Protestant martyrologist, in his 1563 work Actes and Monuments, makes several mentions of James Basset.[17] Having strong Catholic sympathies himself, on his release he fled abroad to Flanders, according to Nicholas Harpsfield (died 1575), "not to be entangled with the schism".[18]

Reign of Queen Mary I

On the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary in 1553, Bishop Gardiner was restored to the See of Winchester and appointed Lord Chancellor and Basset returned from his exile to continue serving him. He received appointments within the royal household and a pension of 1,300 crowns from Mary's consort Philip II of Spain. He was sent on various foreign missions by the queen and her consort, including in January 1558 a mission from London to Brussels to inform King Philip that Queen Mary was pregnant.[19]

Trustee of Earl of Devon

Following the exile in 1555 to the Venetian Republic of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (c. 1527–1556), once a likely husband for Queen Mary, which match had been supported by Bishop Gardiner, Basset became one of the trustees of his extensive English possessions.[20] Basset's step-father Lord Lisle was a relative by marriage to Courtenay.[21] Courtenay made a gift to Basset of his "great horse".[22] An extensive correspondence between Basset and Courtenay survives, amounting to 17 letters in the UK National Archives and 10 in the Venetian Archives[23] The letters in general offer Basset's advice as to the diplomatic and political policy to be followed by Courtney to protect his interests, for example in his first letter from London dated 3 May 1555:[24]

... If your lordship would follow my advice I would wish you to make no tarrying for your better furnishing at Antwerp but with that you have to repair with as convenient speed as may be to the Emperor, and when you have once seen him you may at your pleasure repair again to Antwerp and there furnish yourself at your will. I know with the more expedition you arrive there the better it will be accepted and if you should long delay the time by the way it would be suspicious...

Assassination attempt on Princess Elizabeth

During the reign of Queen Mary, her sister and heir apparent the Protestant Princess Elizabeth is said by John Foxe (died 1587) the Protestant martyrologist,[25] to have been the target of an assassination attempt by Basset, which has been dismissed by Byrne (1981) as "apocryphal":[26]

Another time one of the privy chamber, a great man about the queen and chief darling of Stephen Gardiner named Master James Basset, came to Bladon Bridge, a mile from Woodstock, with 20 or 30 privy coats [soldiers wearing concealed chain-mail[27]] and sent for Sir Henry Benifield to come and speak with him.

The princess's custodian between May 1554 to April 1555 was Sir Henry Bedingfield, who was away, but his brother met Basset at the bridge and "would suffer him in no case to approach in, who otherwise (as is supposed) was appointed violently to murder the innocent lady".

Marriage and progeny

At some time between September 1553[28] and June 1556[29] James Basset married (as her second husband) Mary Roper (died 20 March 1572[30]), daughter of William Roper (1495/6-1578), of St Dunstan's, Canterbury, of Eltham, Kent and of Chelsea, Middlesex, several times an MP for various constituencies, by his wife Margaret More, daughter of Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), Lord Chancellor to King Henry VIII and opponent to the Protestant Reformation.

Widow of Stephen Clarke, [31] Mary was one of the gentlewomen of Queen Mary's privy chamber and at her accession was one of nine ladies attending her, together with Anne Basset, James' sister, on her journey from the Tower of London to the Palace of Westminster on 30 September 1553, the day before her coronation.[32] She was a noted scholar of Greek and Latin and translated the Ecclesiastical History by Eusebius and the works of other of the early Church Fathers, as mentioned by Nicholas Harpsfield (died 1575) in his Life of More.[33] She also translated the Treaty on the Passion by her grandfather Sir Thomas More, which was published in William Rastell's 1557 edition of More's works.[34]

He had by Mary Roper the following progeny:

- Philip Basset (born May 1557[35]), eldest son and heir, who was named after his father's master Phillip II of Spain, who gave presents to Mary Roper on her marriage and was godfather by proxy to Philip Basset at his christening.[36] The Spanish ambassador, count de Feria, gave from King Philip "a great gilt cup", later mentioned in James' will.[37] He trained as a lawyer entering Lincolns Inn on 8 October 1572, from which he was later expelled for recusancy. He was jailed in the Fleet, but probably escaped to Ireland. He married a sister of Richard Verney of Compton Verney in Warwickshire, but had a difficult life due to his adherence to the Catholic religion. By 1595 his fortunes had almost entirely disappeared.[38]

- Charles Basset, 2nd son, born posthumously 1558/9. He too suffered for his recusancy. He was arrested in 1581 as having been associated with the Jesuit priests Edmund Campion (died 1581) and Robert Persons (died 1610) and the Jesuit mission of that year. He was admitted to the English College in Rome in November 1581 with a letter of introduction from Persons to the Rector describing him as " a youth of an illustrious and wealthy family and the great-grandson of Sir Thomas More with talent, manners, virtues worthy of himself and his ancestors". His health broke down in 1583 and he returned to France and died "a most holy death" at Rheims, bequeathing all his possessions to the English College in Rome.[39]

Lands, assets and revenues acquired

- In 1551 he was receiving £4 per annum wages from Bishop Gardiner with a further £14 annuity comprising £4 from the manor of Taunton and £10 from East Mere (sic) (probably East Meon in Hampshire), both episcopal possessions.[40]

- On 10 March 1554 Queen Mary granted him the wardship and marriage of his nephew Arthur Bassett (1541–1586), together with an annuity of £20 payable from his estates.[41]

- On 10 March 1555 "in consideration of his service" and addressed as "Gentleman of the Queen's Privy Chamber" he received from Queen Mary a 30-year lease of lands previously held by Sir Peter Carew (c. 1510–1575), of Mohuns Ottery, Devon, MP, attainted of high treason.[42]

- On 12 May 1555 he was granted by Queen Mary a 30-year lease (in free socage for a rent of £29 3s per annum) of the escheated manor and lordship of Great Torrington, caput of a feudal barony, in North Devon.[43] The grant included Town Mills, all markets and fairs with their profits, various local woodlands and "all other lands and franchises belonging either to the lordship, the borough or the town".[44]

- In 1556, having received the wardship of his nephew Arthur Bassett, he received a lease of many of his lands.[45]

- In February 1556 he acquired an 80-year lease for the rent of 40 shillings per annum from the parson of St Clement Danes of the townhouse in London next to the Savoy Hospital, built and formerly occupied by Sir Thomas Palmer, attainted of high treason for seeking to elevate Lady Jane Grey to the throne.[46]

- On 15 April 1557 he received a grant of the reversion of the office of keeper of Goodmanshide Park at Hunsdon, Hertfordshire and of keeper of the manor and parks of Hunsdon and of steward and bailiff of the honour and lordship of Hunsdon and Eastwick in Hertfordshire.[47]

- On 21 May 1557 Basset received a 40-year lease at the annual rent of £200 of various lands and manors being the eventual inheritance of his nephew Arthur Basset, a minor. The grant was made "at the special suit and petition of Arthur Basset, esquire, now under the age of 21...upon petition of James Basset esquire, one of the gentlemen of the Queen's privy chamber, and in consideration of James Basset's services". The lands included:[48]

- In Devon: Heanton Punchardon, Bulkworthy, Riddlecombe, Heanton Forinseca, Beaford and Mershe and Bickingholt in Devon; the advowsons of Atherington, Bickington, Parkham, Landcross in Devon

- In Gloucestershire: Frampton Cottrell, Westonbirt, Ablington and Sandhurst, and the reversion of other manors.

- In Wiltshire: Asserton

- In Somerset: the reversion of various manors

- On 10 August 1557 James Basset received royal licence to keep a retinue of 20 persons "over and besides all such persons as daily attend upon him in his household"..."and to the same to give him livery, badge or cognizance", and was pardoned for any offences previously committed by him against the Act of Retainers.[49]

- In 1558 in conjunction with Ralph Cholmley (c. 1517–63), of London, MP, he acquired over £2,000 worth of property in Devon.[50]

Death and burial

James Basset died on 21 November 1558, at the start of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, and was buried on 26 November at the "Blackfriars in Smithfield", (sic), London, to whom he bequeathed £20 in his will.[51] A description of his funeral was made in the Diary of Henry Machyn as follows:[52]

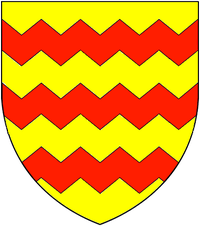

The 26th day of November was buried at the blackfriars in Smithfield Master Basset, squire, one of the Privy Chamber with Queen Mary; and he had two white branches [white candlesticks] and twelve torches and four great tapers and a herald ... a coat armour, a pennon of arms and two dozen of scutcheons.

He was survived by his wife Mary Roper, then pregnant with his second child Charles. It is likely his life under the new Protestant queen would have been one of hardship, possibly of exile or imprisonment.[53]

Succession and bequests

By his will dated 6 September 1558 he bequeathed to his wife her jewels, half his goods, his house in Chelsea and a life interest in his lands. Also he made small bequests to three of his sisters. To his unborn child, Charles Basset, he left the lease of his London townhouse near the Savoy Palace in The Strand. The residue of his un-entailed estate, excepting a few small bequests, he ordered to be sold to pay his debts.

Sources

- Virgoe, Roger, biography of James Bassett published in The History of Parliament: House of Commons 1509–1558, ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981

References

- Virgoe

- Biography in History of Parliament

- Virgoe

- Byrne, vol 1, p.312

- Richard Polwhele, The Civil and Military History of Cornwall, volume 1, London, 1806, pp 106–9; Byrne, vol.1, p.302 states "1485", quoting Public Record Office, Lists & Indexes, vol.IX, List of Sheriffs

- Hart, Kelly (1 June 2009). The Mistresses of Henry VIII (First ed.). The History Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-7524-4835-8.

- Byrne, vol.6, index, p.403

- Sarah Clayton, "Bassett, James (c.1526–1558)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008 accessed 29 October 2009

- Boland, Bridget, ed., The Lisle Letters; An Abridgement, Chicago, 1981, pp.104–110

- Virgoe

- Byrne, vol.1, p.87

- Virgoe

- Byrne, vol.6, p.263

- Virgoe

- Byrne, vol.6, p.262

- Byrne, vol.6, p.264

- Foxe, John, Actes and Monuments, 1563, ed. Cattley S.R. & Townsend, George, 8 vols., 1837–41, ed. Pratt, Josiah, 1870

- Harpsfield, Nicholas, The English Works, introduction to Mary Roper's translation of Sir Thomas More's History of the Passion, quoted by Byrne, vol.6, p.264

- Byrne, vol.6, p.271

- Virgoe

- Byrne, vol.6, p.266

- Byrne, vol.6, p.269

- Byrne, vol.6, p.269; printed in Venetian Calendar, vol.6

- State Papers 11/5, no.9, quoted by Byrne, vol.6, p.269-70

- Foxe, John, Actes and Monuments, 1563, ed. Cattley S.R. & Townsend, George, 8 vols., 1837–41, ed. Pratt, Josiah, 1870, vol.7, p.596

- Byrne, vol.6, p.267

- Byrne, vol.6, p.267

- Byrne, vol.6, p.264

- VirgoeM

- Byrne, vol.6, p.274

- Byrne, vol.6, p.264

- Byrne, vol.6, pp.264–5

- Byrne, vol.6, p.265

- Virgoe

- Per 1559 Inquisition post mortem of James Basset, confirmed by that of 1572 of his mother; given incorrectly (as noted by Byrne) by Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, pp.45–48, pedigree of Basset, p.47

- Virgoe;

- Byrne, vol.6, pp.265–6

- Byrne, vol.6, p.276

- Byrne, vol.6, p.276

- Byrne, vol.6, p.262

- Byrne, vol.6, p.267

- Virgoe; Byrne, vol.6, p.268

- Byrne, vol.6, p.268; Pole, Sir William (died 1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, pp.392–3; Alexander, J.J. & Hooper, W.R., History of Great Torrington, Sutton, 1948, p.64

- Byrne, vol.6, p.268

- Virgoe

- Byrne, vol.6, p.271

- Byrne, vol.6, p.273, note 2

- Byrne, vol.6, p.271-2

- Byrne, vol.6, p.272

- Virgoe

- Identification of institution unclear: St Bartholomew's Priory, of the Augustinian order, was located in Smithfield, whilst the Dominican (Black Friars) Blackfriars, London was located between Ludgate Hill and the River Thames

- Diary of Henry Machyn, ed. J.G. Nichols, 1848, p.179, quoted by Byrne, vol.6, p.274

- Virgoe