John Basset (1462–1528)

Sir John Basset (1462–31 January 1528), KB, of Tehidy in Cornwall and of Umberleigh in Devon was Sheriff of Cornwall in 1497, 1517 and 1522 and Sheriff of Devon in 1524. Although himself an important figure in the Westcountry gentry, he is chiefly remembered for his connection with the life of his second wife and widow Honor Grenville (d. 1566), who moved into the highest society when she remarried to Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle KG (d. 1542), an illegitimate son of King Edward IV, and an important figure at the court of King Henry VIII, his nephew. The survival of the Lisle Letters, a large collection of letters to Lisle and his wife Honor, makes their lives two of the best-documented of the period. Honor retained for life as her widow's dower several Basset estates including Umberleigh and Tehidy, and the Lisle Letters include a great deal of correspondence to Honor from her stewards concerning their detailed management. They also include much correspondence to her from her children by Sir John Basset.

Origins

He was the eldest son and heir of Sir John Basset (1441–1485) of Tehidy in Cornwall and Whitechapel in the parish of Bishops Nympton, by his wife Elizabeth Budockshyde.[1] His father was the son and heir of John Basset (1374–1463) by Joan Beaumont, daughter of Sir Thomas Beaumont of Umberleigh and Heanton Punchardon and sister and heiress of Philip Beaumont of Shirwell. The Beaumonts had inherited Umberleigh from the Poulton family who had inherited it from the Willingtons.[2] The Basset family were amongst the early Norman settlers in England.

Career

As Sheriff of Cornwall in 1497 Sir John was a target for the Cornish rebels under Richard Pendyn of Pendeen who attacked and 'dismantled' Tehidy, the family home. He was created Knight of the Bath by King Henry VII in November 1501 at the time of the marriage of his son and heir Prince Arthur to Katherine of Aragon. He was Sheriff of Cornwall again in 1517 and 1522 and Sheriff of Devon in 1524. In 1520 he was part of the Devonshire contingent of the large entourage which accompanied King Henry VIII to the Field of Cloth of Gold.

Beaumont inheritance

Sir John Basset as well as being heir to his extensive paternal lands was also heir to his maternal grandmother Joan (or Johanna) Beaumont[3] (wife of John Basset (1374–1463)), the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas Beaumont (1401–1450) of Shirwell by his wife Philippa Dinham, daughter of Sir John Dynham (1406-1458)[4] of Nutwell, Kingskerswell and Hartland. Joan Beaumont was heiress to her brother Sir Philip Beaumont (1432–1473), MP in 1467 and Sheriff of Devon in 1469, and also to her mother Phillipa Dynham.[4]

These former Beaumont lands included the manors of Umberleigh and Heanton Punchardon in North Devon. However, as deduced by Byrne (1981), Basset lacked the financial resources to recover his inheritance,[5] which involved paying fines and recoveries to the King. At the time he had been married for 30 years[5] to his first wife Elizabeth Denys and had given up any hope of producing a surviving son and heir. In order to make the best of his situation, he obtained financing for the recoveries from Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney (1451–1508), KG, under a special agreement entered into in 1504, referred to by the family as the "Great Indenture".[6] This specified that Daubeney would pay about £2,000 for the recoveries on condition that one of the Basset daughters and co-heiresses would marry Daubeney's son Henry Daubeney (1493–1548) (later created Earl of Bridgewater), then aged 10, before his 16th birthday. The purpose was to entail the Beaumont lands upon the male issue of a Daubeney-Basset marriage, thus increasing the future wealth of the Daubeney family. However the indenture allowed for Sir John Basset and any future wives of his to retain possession during their lives of Umberleigh and lands in Bickington. If the scheme should fail due to the marriage not taking place and in default of other provisions, the lands would revert to the right heirs of Basset. To this effect Basset sent two of his four daughters by Elizabeth Denys, namely Anne and Thomasine, to live in the Daubeney household. The marriage never did take place and Lord Daubeny died four years later in 1508. Whether for those reasons or another the gamble paid off for Basset as his 2nd wife Honor Grenville produced for him a son and heir in 1518 and the Beaumont lands came back to the Basset family. During the time when the agreement was operative the deeds to the properties concerned were kept in safe custody by Richard Coffin (1456–1523)[7] of Portledge, Sheriff of Devon in 1510,[8] the Beaumont's tenant at Heanton Punchardon and at East Hagginton[9] (in the parish of Berrynarbor), who was clearly trusted by both parties,[10] and whose Easter Sepulchre tomb survives in the chancel of Heanton Punchardon church.[11] Basset's son George later married Richard Coffin's great-granddaughter Jacquet Coffin.[12] The custody of these deeds forms an important topic in the Lisle Letters.[13]

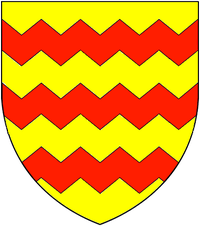

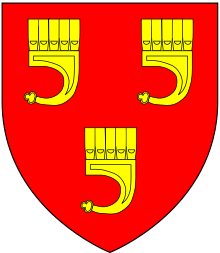

Armorials

_Arms.png)

The chest tomb of Sir John Basset in Atherington Church displays heraldry sculpted on two stone shields on the north side, showing Basset with quarterings of Beaumont and Willington impaling on separate shields the arms of his two wives. On the slab top of the tomb were originally four brass shields, three of which survive, two with identical arms as the stone shields on the north side, the third showing the arms of Basset alone quartered with Beaumont and Willington.

Marriages and progeny

Sir John Basset married twice, producing in total 12 children. His first wife failed to provide him with a surviving son and heir and he appears to have lost all hope of having a son, hence his conveyance of his Beaumont inheritance to Lord Daubeney, retaining only Umberleigh for his life. However, after a long marriage his first wife died unexpectedly and Basset found himself at the age of 53 remarried to a new 22-year-old bride, who would provide him with the desired son and heir. The problem then was how to recover for him the Beaumont inheritance conveyed to Lord Daubeney. This legal struggle, which Lady Lisle pursued vigorously over many years and which was ultimately successful, occupies much of the Lisle Papers.

First marriage

- Firstly before 1474[18] to Elizabeth[19] (or Ann[20]) Denys, daughter of John Denys of Orleigh, near Bideford, by his wife Eleanor Giffard (daughter and co-heiress of Stephen Giffard of Thuborough[21]) by whom he had the following progeny, one son, who died young,[22] and four daughters:

- Unknown son Basset, died young

- Anne Basset, who as a child had been sent by her father, together with her sister Thomasine, to live in the household of Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney (1451–1508), under a special agreement entered into in 1504, referred to by the family as the "Great Indenture".[6] This specified that Daubeney would pay about £2,000 for the recoveries of Basset's Beaumont inheritance on condition that one of the Basset daughters and co-heiresses would marry Daubeney's son Henry Daubeney (1493–1548), on whom the lands were entailed. The marriage never took place and in 1511 she married James Courtenay (born 1459) of Upcott in the parish of Cheriton Fitzpaine,[23] Devon, a younger son of the first Sir William Courtenay (d.1485) of Powderham by his wife Margaret Bonville[24] a daughter of William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville (d. 1461). James's eldest brother was Sir William Courtenay (1477–1535) "The Great",[25] who was responsible for giving the order for the pulling down of Umberleigh weir in November 1535, much to the opposition of Lady Lisle.[26]

- Margery[27] or Mary[28] Basset who married William Marrys of Marrys in Cornwall (i.e. Marhayes Manor, Week St Mary, Cornwall).[28] The manor of Marrys was adjacent to the Basset manor of Femarshall, part of which Margery had as her dower.[29] William died leaving a young daughter Margaret Marrys (d.1621) as his sole heiress. Her wardship and marriage was purchased by the North Devon lawyer George Rolle (c.1486-1552) of Stevenstone, who later was an important adviser to John Basset's widow Honor Grenville, later Lady Lisle. In his will Rolle left Margaret's wardship to his son George Rolle (d.1573), who therefore chose to marry her himself.[30] George Rolle (d.1573) named one of his daughters Honor, apparently after Lady Lisle, as his elder brother John Rolle had done for one of his daughters also.[31]

- Jane Basset.[32] Six of Jane's letters, written when aged in her 40s, to her step-mother Lady Lisle survive in the Lisle Papers.[33] Lady Lisle had legal possession for life of Umberleigh as her dower, but allowed Jane and her blood-sister Thomasine to live there. Jane was a talkative and assertive character.[34] Jane's presence at Umberleigh from 1533 was resented by Lady Lisle's servants there, whom Jane believed were not looking after the property adequately and were defrauding their mistress, for example by selling salmon and accounting for only part of the proceeds.[35] She wrote to Lady Lisle that while she was away at Calais (1533-1542) with Lord Lisle, that her servants, including Rev John Bonde her bedesman and Vicar of Yarnscombe, kept a prostitute in the house and maintained a "bawdy and unthrifty rule" at the manor. She clearly was fond of Umberleigh, and perhaps resentful of her young step-brother John Basset who would himself inherit it.[36] She occupied the "corner chamber" and the buttery[37] and was reported to have had a greyhound which slept on the bed most of the day. She was allowed by Lady Lisle pasture in the park for 2 cows, but defiantly pastured 3 cows and a horse, which was reported by Rev Bonde to Lady Lisle. She asked Lady Lisle to lease her the fishing rights on the River Taw to supplement her small income.

- Thomasine Basset[38] (d.1536). As a child she had been sent by her father, together with her sister Anne, to live in the household of Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney (1451–1508), under a special agreement entered into in 1504, referred to by the family as the "Great Indenture".[6] This specified that Daubeney would pay about £2,000 for the recoveries of Basset's Beaumont inheritance on condition that one of the Basset daughters and co-heiresses would marry Daubeney's son Henry Daubeney (1493–1548), on whom the lands were entailed. The marriage never took place. It is not known if she ever married. Aged in her 40s, she lived with her blood-sister Jane Basset at Umberleigh whilst Lady Lisle was away at Calais, but as was reported in one of Jane's letters, ran away early one morning to her sister Margaret's house at Marrys. Wood (1846) suggested an elopement had occurred, discounted by Byrne who suggested she was perhaps fleeing from her domineering sister Jane.[39] Jane saw it as a conspiracy by Thomasine and the servants to persuade her to leave too. Thomasine became ill at Marrys and was apparently on her way back to Umberleigh when she died 18 months later at Dowland on the Friday before Palm Sunday 1536.[34]

Second marriage

- Secondly when he was 53, in 1515,[40] to Honor Grenville (1493–1566), a daughter of Sir Thomas Grenville (died 1513), Sheriff of Cornwall in 1481 and in 1485/6,[41] (whose monument and effigy exists in Bideford Church) of Stowe in Kilkhampton, Cornwall and lord of the Manor of Bideford, Devon, by his wife Isabella Gilbert, by whom he had the following eight children (7 surviving):

- John Basset (1518–1541), eldest son and heir, who married Frances Plantagenet, the daughter and co-heiress of his step-father Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle, bastard son of King Edward IV (she married secondly Thomas Monke (died 1583), of Potheridge in Merton, Devon (as his first wife), with whom she had three sons and three daughters. By her eldest son she was great-grandmother of George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (1608–1670), KG.[42] By Frances Plantagenet John Basset had a son and heir Sir Arthur Basset (1541–1586), MP, of Umberleigh and a daughter married to William Whiddon.[43] Due to his Plantagenet ancestry, Arthur's son Sir Robert Basset (1573–1641) made what turned out to be a foolish and costly decision to offer himself as one of the many claimants to the throne of England after the death of Queen Elizabeth, perhaps encouraged by his father-in-law Sir William Peryam, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer.[44] He suffered a heavy fine for his action which according to the biographer John Prince (died 1723), involved the sale of thirty of the family's manors.[45]

- George Basset (c. 1524 – c. 1580), 2nd son, MP for Newport-juxta-Launceston in 1563 & 1572 and for Bossiney in 1571.[46]

- James Basset (1526–1558), 3rd son and youngest child,[18] MP,[47] a courtier first to Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor and later a courtier to Queen Mary I. He built up his own substantial estate in lands and was granted by Queen Mary the manor of Great Torrington.[48]

- Honor Basset, christened in 1515,[49] assumed to have died young

- Philippa Basset (d.1582), wife of James Pitts of Overcombe, possibly a son of Richard or William Pitts who appear on the lay subsidy roll of February 1526 for Atherington.[50]

- Katharine Basset (b.circa 1522), (sometimes erroneously referred to as "Elizabeth") a servant to Queen Anne of Cleves, wife of Sir Henry Ashley (1519–1588), MP, of Hever in Kent, later of St Giles, Upper Wimborne in Dorset[51]

- Anne Basset, maid of honour successively to Queens Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard and Katharine Parr;[52] and said to have been a mistress of King Henry VIII.[53] As a child she went with her mother and step-father Lord Lisle to Calais, and in November 1533 entered the household of Thybault Rouaud, Sire de Riou (d.1556), at Pont de Remy near Abbeville.[54] He was a friend of Lord Lisle's and his sister Anne Rouaud was the wife of Nicholas de Montmorency, into whose household entered Anne's sister Mary Basset. She married Francis Hungerford[51]

- Mary Basset[55] (d.1598), youngest daughter. She went with her mother and step-father Lord Lisle to Calais, and in August 1534, aged about 11 or 12, she entered the household at Abbeville of Nicholas de Montmorency, Sire de Bours (d.1537), a branch of the premier family of France the House of Montmorency.[56] She remained there for almost 4 years,[57] following which she returned to Calais. In Lent 1540 she was secretly engaged to her former guardian's son Gabriel de Montmorency, Seigneur de Bours, who had proposed marriage to her.[58] This closeness to a subject of the French king was incriminating evidence in Lord Lisle's arrest for treason, followed by the arrest of Mary herself, with her mother and sister Philippa Basset.[59] Following her release from house arrest at Calais in 1542 she became in 1557 the wife of John Wollacombe of Combe, Roborough, Devon.[60] She died and was buried on 21 May 1598 at Roborough, Devon, having produced several children.[61]

Remarriage of his widow

His wife Honor remarried, to Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle, who was the illegitimate son of King Edward IV. Whilst Lord Lisle was the Governor of Calais, John Basset's children were moved there and were educated in France. Lord and Lady Lisle were apparently very happily married. Honor was a forceful woman, who wrote many letters to friends at court, ensuring that they were kept well-informed. These letters are preserved today as the Lisle Letters and give a valuable account of developments during the reign of Henry VIII.

Career of daughters at court

Honor finally succeeded in getting one of her young daughters appointed as a maid-of-honour to Queen Jane Seymour in 1537, who had asked her to send two to court for her selection. She chose Anne over Catherine. Anne Basset subsequently became known at court for her beauty and respectability. Her first appearance as maid-of-honour was at Jane Seymour's funeral. During the interval of two years whilst the king remained without a new wife Anne spent much time at court and received expensive presents from the King. She went on to serve three more Queens, Anne of Cleves, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parr. Despite Lord Lisle's arrest for treason in 1540, her sister Katherine Basset, and her mother eventually joined her at court.

Daughter possible bride for King Henry VIII

In 1542 Chapuys, the Imperial ambassador, reported that on the eve of Catherine Howard's execution, the king appeared besotted with Anne Basset, and that she was a possible sixth wife. This eventuality may have been ruined by Anne's own family as her sister Elizabeth Basset favoured the King marrying her own mistress, Anne of Cleves, and made comments implying that this seemed to be what God wanted. She also said, "What a man is our king? How many wives will he have?", which was reported to the King and resulted in her being judicially questioned, a serious matter as under the treason laws her remarks might have warranted the death penalty. The Basset family continued to serve at the courts of Henry VIII's children.

Death and burial

Sir John died on 31 January 1528 aged 66. Some of his children were still infants and the wardship and marriage of his son and heir John Basset aged 9 was purchased for 200 marks jointly by his mother Honor and John Worth of Compton Pole.[62] The wardship was later acquired by his step-father and future father-in-law Viscount Lisle before 1532[63] Sir John Basset was buried in his family's private Holy Trinity Chapel (now largely demolished), next to his manor house of Umberleigh.

Will

Sir John Basset left a will dated 6 November 1527, now lost but of which parts were transcribed by the 18th-century herald Anstis.[64] He listed his feoffees, amongst whom were Roger Graynfild (i.e. Grenville), who were directed to "keep every year a solemn dirige and the morrow upon three masses for the good estate of the said Sir John Basset and Honour his wife" and of various members of the Grenville family.[64] He left his wife Honor, until she remarried, all the rents and profits of his manors of Trevalga, Femarshall, Whitechapel, Holcombe, Upcott Snellard and Calston, from which she was to pay his debts and also provide dowries of 100 marks each on the marriages on each of his daughters Jane, Thomasine, Philippa, Katharine and Mary.[64] His marriage settlement of 1515 had already provided that Honor should have as her jointure the manor and advowson of Tehidy, the manor of Umberleigh, and lands in Bickington and Atherington.[65]

Monument

His chest tomb with monumental brasses on top, of himself between his two wives with his children below in two small groups exists in St Mary's Church, Atherington, to where it was moved in 1818 from Umberleigh Chapel.[66] The Lisle Letters record some details concerning the making of the tomb. His widow Lady Lisle ordered "images & scripture...for Mt Basset's tomb" before she departed for Calais[67] to join her new husband, and a letter from Richard Kyrton to Lady Lisle dated 21 November 1533 states: "And as for your plates for the tomb, they are sent home by the carrier, and for the gilding they must descry all the arms by the reason of colours. And they asketh £ v for the doing of it and for the making Master George Rolles hath laid out xxxiii s iiii d unto Candlemas, the which Burye then must pay him".[68] In a letter dated April 1534[69] Sir John Bonde wrote to Lady Lisle "the pictures of Mr Basset's tomb" have been "laid on by the hands of Oliver Tomlyng". Thus the brasses were made in 1533 and set onto the tomb in 1534.[70] A letter to Lady Lisle from George Rolle[71] referred to an inscription on the tomb, which is now missing.

See also

- Baron Basset

- Great Cornish Families

- Tehidy Country Park

- Francis Basset

- Francis Basset, 1st Baron de Dunstanville and Basset

- Frances Basset, 2nd Baroness Basset

Sources

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1, pp. 299–350, "Grenvilles and Bassets" & vol.4, Chapter 7 re "The Great Indenture"

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, esp. pp. 45–48, pedigree of Basset

References

- The Lisle Letters: An Abridgement, By Muriel St. Clare Byrne

- Risdon, Tristram, Survey of Devon, 1810 edition, p. 317

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 312

- Vivian, p. 46

- Byrne, p. 313

- Transcribed in Byrne, vol.4, chapter 7, appendix 2

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605; Vivian, p. 208, pedigree of Coffin; Byrne, vol.1, p. 606: "died in Dec 1523 at age of 77"

- Risdon, Tristram (d. 1640), Survey of Devon, 1811 edition, London, 1811, with 1810 Additions; Pevsner, p. 477

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605; East Hagginton had descended to the Beaumonts from the Punchardon (Pont de Chardin") family of Heanton and in Risdon's time (d. 1640) was still held by the Coffin family. In 1810 it had reverted to the Bassets (Risdon, pp. 347, 431)

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605–6

- Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p. 477

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605; Vivian, pp. 47,209

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605

- These arms of Willington a saltire vair are shown on the tomb in Barcheston Church, Warks., of William Willington (died 1555), of Willington manor and his wife Anne, whose alabaster effigies lie on top of the tobm (Victoria County History, Vol.5, Warwickshire, Kington Hundred). Also same arms listed in Heralds' Visitation of Warwickshire, 1619 (Wellington de Hurley): Gules, a saltire vair. The Dering Roll of Arms lists the arms of "Rauf de Wiltone" as Gules, a saltire vair. Tristram Risdon in his Survey of Devon (1630) gives the arms of Willington of Umberleigh apparently incorrectly as: Party per pale dente argent and gules, a chief or (1810 edition, p. 317) and these arms are shown in 19th-century stained glass in Atherington Church impaling the arms of Champernowne: Gules, a saltire vair between 12 billets or

- Vivian, Heraldic Visitationms of Devon, 1895, p.281, pedigree of Denys of Orleigh; as seen on ledger stone of Elizabeth Denys (1625–1664) on floor of Orleigh Chapel, Buckland Brewer Church, Devon

- Byrne, vol.2, letter 239, p.224

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1, Appendix 6, "The Atherington Brass", p.700; The Lisle Letters record some details concerning the making of the tomb. Lady Lisle ordered "images & scripture...for Mt Basset's tomb" before she departed for Calais to join her new husband Lord Lisle, and a letter from Richard Kyrton to Lady Lisle dated 21 November 1533 states: "And as for your plates for the tomb, they are sent home by the carrier, and for the gilding they must descry all the arms by the reason of colours. And they asketh £v for the doing of it and for the making Master George Rolles hath laid out xxxiii s iiii d unto Candlemas, the which Burye then must pay him".(Byrne, 1981, vol.1, letter 79, p.620) In a letter dated April 1534 (Byrne, 1981, vol.3, letter 516) Sir John Bonde wrote to Lady Lisle "the pictures of Mr Basset's tomb" have been "laid on by the hands of Oliver Tomlyng". Thus the brasses were made in 1533 and set onto the tomb in 1534.(Byrne, 1981, vol.1, Appendix 6, "The Atherington Brass", p.700)

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 312

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1, p.312. Byrne argues in detail that John Basset's first wife was Elizabeth Denys not her sister Anne Denys

- Per Vivian, Heraldic Visitations of Devon, pp. 46 & 281

- Vivian, p. 281, pedigree of Denys of Orleigh; Thuborough (Pevsner, p.771) in parish of Sutcombe, 5 miles north of Holsworthy (Risdon, pp. 248–9)

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 312. Depicted on the Atherington Brass

- Risdon,pp.93-4

- Collins Peerage & http://www.tudorplace.com.ar/HUNGERFORD.htm#Elizabeth HUNGERFORD1

- Visitation of Devon, 1895 ed., p.246

- Byrne, vol.2, pp675-6

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 312; Vivian, p.656

- Vivian, p.46

- Byrne, vol.2, p.401

- "ROLLE, George (by 1486-1552), of Stevenstone, Devon and London. - History of Parliament Online".

- Byrne,vol2,p.212; Vivian, p.653, 656

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 312; given incorrectly in Vivian, p.47 as daughter of Honor Grenville

- Byrne, vol.3, p.56

- Byrne, vol.3, p.63

- Byrne, vol.3, pp.38-67

- The accusation was made that she "do covet to have my brother's evidence" (i.e. title deeds), Byrne, vol.3, p.57;63

- Byrne, vol.3, p.47

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 312; given incorrectly in Vivian, p. 47 as daughter of Honor Grenville

- Wood, Mrs M.A.E., Letters of Royal and Illustrious Ladies, 1846, vol.2, p.143; Byrne, vol.3, p.63

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 308, Inq post mortem of John Basset refers to marriage settlement deed dated 15 December 1515

- Richard Polwhele, The Civil and Military History of Cornwall, volume 1, London, 1806, pp 106–9; Byrne, vol.1, p. 302 states "1485", quoting Public Record Office, Lists & Indexes, vol.IX, List of Sheriffs

- Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Proceedings, Volume 44, p.12

- Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Proceedings, Volume 44, p. 12

- Biography of Sir Robert Basset in History of Parliament

- Prince's "Worthies of Devon", biography of Col. Arthur Basset (1597–1672)

- http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/bassett-george-1524-c80; Vivian, p. 47; Byrne, vol 1, p. 313

- Biography in History of Parliament

- Alexander, J.J. & Hooper, W.R., History of Great Torrington, Sutton, 1948, p. 64

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 308

- Byrne, vol 6, p. 276, quoting Atherington parish register; Byrne, vol 1, p. 308–10

- Vivian, p. 47

- Byrne, vol.6, p. 277

- Hart, Kelly (1 June 2009). The Mistresses of Henry VIII (First ed.). The History Press. pp. 175–178. ISBN 0-7524-4835-8.

- Byrne, vol.3, p.133

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 313

- Byrne, vol.3, pp.134-7

- Byrne, vol.6, p.142

- Byrne, vol.6, pp.140-1

- Byrne, vol.6, p.148

- Vivian, pp. 47, 795; Byrne, vol.6, p.280; Risdon, Survey of Devon, 1811 ed. p.270

- Byrne, vol.6, p.280

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 315

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 316

- Byrne, vol 1, p. 314

- Byrne, vol 1, pp. 314–5

- Byrne, 1981, vol.1, Appendix 6, "The Atherington Brass", p. 699

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1, Appendix 6, "The Atherington Brass", p.700

- Byrne, 1981, vol.1, letter 79, p. 620

- Byrne, 1981, vol.3, letter 516

- Byrne, 1981, vol.1, Appendix 6, "The Atherington Brass", p. 700

- Byrne, 1981, vol.1, Appendix 6, "The Atherington Brass", p. 699, referring to Vol 2, letter 239