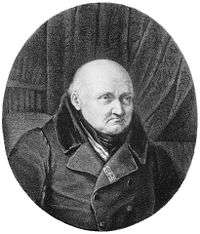

Józef Kalasanty Szaniawski

Józef Kalasanty Szaniawski (1764 in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska – 16 May 1843 in Lwów) was a Polish philosopher and politician.

Life

During the Kościuszko Uprising (1794) Szaniawski was a Polish Jacobin. After the suppression of the uprising, he emigrated to Paris, where he was a member of the "Polish Deputation" (Deputacja Polska),[1] an independence organization that arose in Paris in 1795 (remaining active till 1796) and grouped representatives of the Polish émigré radical wing. The Polish Deputation hoped to bring about an armed uprising and social revolution in occupied Poland with the support of revolutionary France.[2] The Polish Deputation thereby came into conflict with the moderate Kościuszko-Uprising émigré activists of the "Agency" (Agencja), founded in Paris in 1794, which opposed armed action in Poland, counting instead on France's diplomatic and military aid, and supporting Henryk Dąbrowski's Polish Legions.[3]

On returning to Warsaw during the Prussian occupation, Szaniawski co-edited Gazeta Warszawska (The Warsaw Gazette) and initiated "Korespondencja w materiach obraz kraju i narodu polskiego rozjaśniających" ("Correspondence on Matters Elucidating the Picture of Poland and the Polish People"). He became secretary of the Society of Friends of Learning and president of the Society for Elementary Textbooks, and headed the censorship.[4] A former student of Kant's in Königsberg, he waged a campaign in favor of Kantism.[5]

From 1802 to 1808 Szaniawski published his philosophical works in rapid succession. He expounded Kant's philosophy, but with a special purpose—to turn people's minds toward learning; and, in learning, to break with Enlightenment philosophy, which he condemned for dogmatic unbelief and morally damaging hedonism. He was the first to lead the campaign against the Enlightenment in Poland. He became an apostle of German philosophy and was the first to introduce it into Poland.[6]

Szaniawski especially urged the study of Kant; but, having accepted the fundamental points of the critical theory of knowledge, he still hesitated between Kant's metaphysical agnosticism and the new metaphysics of Idealism. He owed a particular debt to Schelling. Thus this one man introduced to Poland both the anti-metaphysical Kant and the post-Kantian metaphysics.[7]

He introduced them, but later disavowed them. He had entered the civil service and rose quickly to high station, becoming attorney general of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807–15), then secretary of the Provisional Government, then referendary of state under the Congress Poland. A curious change came over him: not only did he lose interest in philosophy, but now he sought to restrain its development. When toward the end of his life, in 1842, he spoke about philosophy, it was only to represent all its theories as a pack of errors.[8]

Works

- O naturze i przeznaczeniu urzędowań w społeczności (On the Nature and Purpose of Offices in Society, 1808)

- Uwagi względem wychowania i nauk (Remarks on Education and Learning, 1821).[9]

See also

- History of philosophy in Poland

- List of Poles

Notes

- "Szaniawski, Józef Kalasanty," Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), vol. 4, p. 341.

- "Deputacja Polska," Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), vol. 1, p. 581.

- "Agencja," Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), vol. 1, p. 29.

- "Szaniawski, Józef Kalasanty," Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), vol. 4, p. 341.

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "Outline of the History of Philosophy in Poland," p. 83.

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "Outline of the History of Philosophy in Poland," p. 83.

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "Outline of the History of Philosophy in Poland," pp. 83–84.

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "Outline of the History of Philosophy in Poland," p. 84.

- "Szaniawski, Józef Kalasanty," Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), vol. 4, p. 341.

References

- "Szaniawski, Józef Kalasanty," Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), Warsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, vol. 4, 1976, p. 341.

- Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN (PWN Universal Encyclopedia), Warsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, vol. 1, 1973.

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "Outline of the History of Philosophy in Poland," translated from the Polish by Christopher Kasparek, The Polish Review, vol. XVIII, no. 3, 1973, pp. 73–85.

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Zarys dziejów filozofii w Polsce (A Brief History of Philosophy in Poland), [in the series:] Historia nauki polskiej w monografiach (History of Polish Learning in Monographs), [volume] XXXII, Kraków, Polska Akademia Umiejętności (Polish Academy of Learning), 1948. This monograph draws from pertinent sections in earlier editions of the author's Historia filozofii (History of Philosophy).