Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos

Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos (Spanish pronunciation: [ikstlawaˈkan ðe los memˈbɾiʎos]) is a town and municipality, in Jalisco in central-western Mexico. The municipality covers an area of 184.25 km². It is located north of the Chapala municipality.

Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos | |

|---|---|

Municipality and city | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

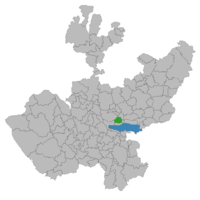

Location of the municipality in Jalisco | |

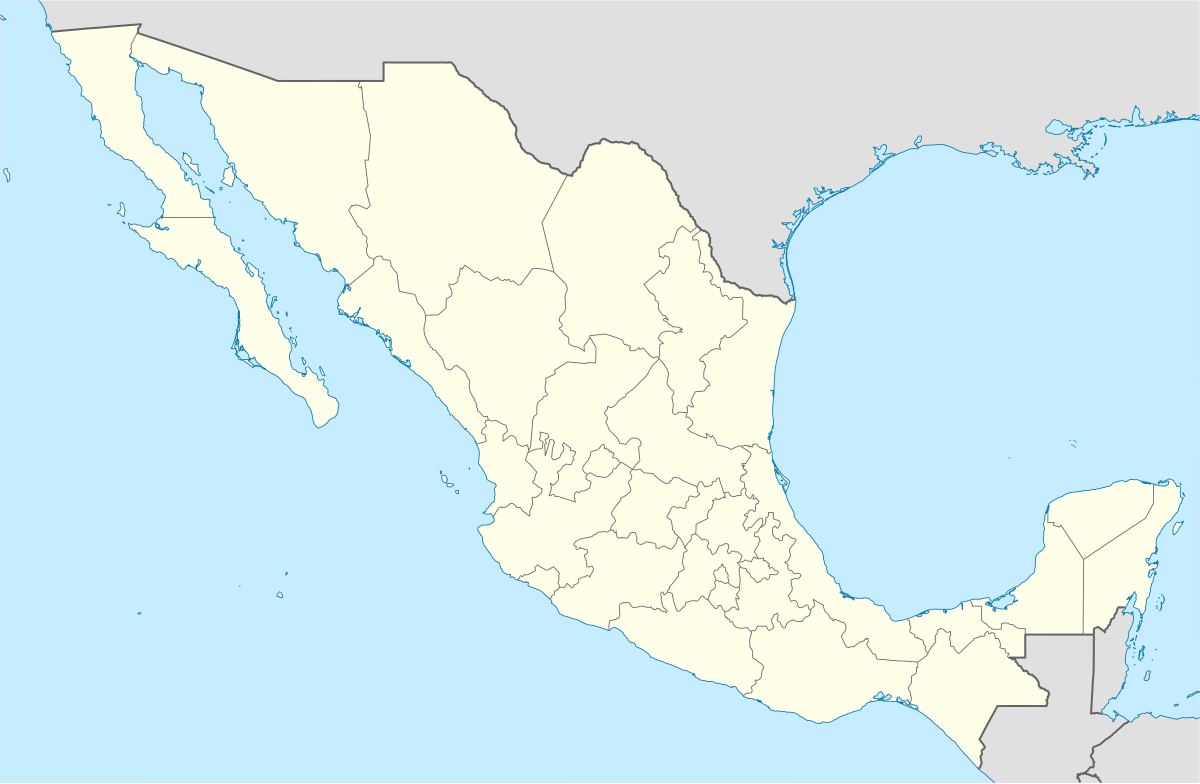

Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos Location in Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 20°21′N 103°11′W | |

| Country | |

| State | Jalisco |

| Area | |

| • Total | 184.25 km2 (71.14 sq mi) |

| Population (2005) | |

| • Total | 23,420 |

| Website | http://www.ixtlahuacandelosmembrillos.gob.mx/ |

In 2005, the municipality had a total population of 23,420.[1]

Geography

Ixtlahuacan de los Membrillos is located in the center of the State, at the coordinates 20-21'00 to 20-27'30 north latitude and 103-07'20 at 103-17'00 west longitude, at a height of 1,570 msnm'meters above sea level.

It is bordered to the north by the municipalities of Tlajomulco de Zuñiga and Juanacatlán, to the south by Chapala, to the east by Juanacatlán and Chapala, and to the west by Tlajomulco de Zúñiga and Jocotepec.

Its territorial extension 184.25 km2, with 94 localities, being the most important: Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos (municipal head), Atequiza, La Capilla, Los Cedros, El Rodeo and Santa Pink.

Flat areas represent 62% of the municipal territory, with heights of 1,500 to 1,600 meters; semi-flat zones account for 20% of the territory, with heights of 1,600 to 1,700 meters; and rugged areas account for 18% of the territory, with heights of 1,700 to 2,300 meters above sea level.

Climate

The climate is classified as semi-dry with dry winter and spring, and semi-warm without defined winter season. The average annual temperature is 19.8oC, and has an average annual rainfall of 797.9 millimeters with a rainfall regime in June, July and August. The prevailing winds are east and west. The average number of frost days per year is 8.2.

Natural Resources

The resources of the municipality are part of them: the Rio Grande de Santiago-Río Santiago and the streams flowing during the los Sabinos rainy season, Los Lobos, Agua Escondida (Jalisco)' Escondida Water, Los Pinos, La Cañada and Grande.

It has storage dams: El Llano, El Carnero, Las Campanillas, La Capilla, El Carrizo and El Aniego.

The dominant soils belong to the type pelicver vertisol and planeeric sun; and as associated soil is the Haptic Feozem type.

The flora is represented by species such as Pinus-pine, oak, oyamel, eucalyptus, Laurel of India, Galeana, Pinabete, willow, sabino, ozote, mezquite, guamúchil, guaje, ash, walnut, guayabo, tepehuaje, Mangifera indica-mango, lemon tree, orange, copal, white zapote, tabachín, jacaranda, camichín, zalate, ahuilote, plum, pirul, nopal and other species.

In the fauna there are species such as coyote, oryctolagus cuniculus-rabbit, Dasypodidae-armadillo, tlacuache, squirrel and rattlesnake.

History

About four kilometers west of Ixtlahuacán, at the foot of the highest hill known as "El Picacho," there is a place called "El Varal" because it is a place where "Las Varas" abound, which are long and thin sticks that were previously used to make tapeixtes, huacals, brambles, fences and huts.

In "El Varal" there is an uncovered and flat plateau where from 1513 to 1534 a tribal group from Tlajomulco de Zúñiga' lived Tlajomulco. This group was precisely that of Don Francisco Tepotzin who had just left Tlajomulco de Zúñiga" Tlajomulco. Adjacent to "El Varal" there is another extensive paddock known all as "La Quebrada".

According to legend, in 1533, by the revelation of their god, the inhabitants of "El Varal" were aware that they should find another place to settle because the place where they were would sink and, therefore, they would die if they did not abandon it. By this same revelation they were made to know that they should go up, at night, to a high part on the hillside and that, facing east, they will seek a very bright light. That would indicate precisely where they should be established.

To the south of what is now Ixtlahuacán there was a spring known as "The Eye of Water". The water from that spring ran down to the north, so extensive puddles formed on the plain. At night, in the water of these puddles, from afar you could see the bright reflected light of the morning lucero that has become the planet Venus.

That bright light is what our ancestors of "El Varal" saw from somewhere on the mountainside "El Picacho". The hitherto inhabitants of "El Varal" according to the indicated signal moved to what is now Ixtlahuacan, but did not settle in the plain, but chose to do so in the vicinity where the spring "The Eye of Water" was still, more than four times centenary, a tree known as "Sabino". Years later, indeed if there was a considerable sinking, not exactly in what is "El Varal" but in the vicinity, in a place called "Mexiquito" but now better known as "La Quebrada". Today we still notice the depression of the terrain, although already very disguised by the thick vegetation.

The May 4, 2020, arrest of Giovanni López Ramírez, a 30-year-old construction worker, and his murder while in police custody the next day, set off violent protests against police brutality in Guadalajara in June 2020 which were met by increased arrests and police represion. López's arrest was supposedly because he was not wearing a facemask outside his home during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico, and the demonstrations can be indirectly tied to the George Floyd protests in the United States.[2][3]

References

- "Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos". Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México. Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. Archived from the original on November 29, 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- "Así fue la detención de Giovanni López justo antes de su muerte". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 5 June 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- "Queman patrullas en Jalisco por muerte de Giovanni López". El Universal (in Spanish). 4 June 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.