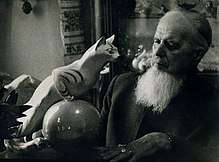

Ivan Efimov

Ivan Efimov (Russian: Иван Семёнович Ефимов 11 February 1878 – 7 January 1959) was a Russian sculptor. Along with his wife, Nina Simonovich-Efimova, the couple founded the tradition of Soviet puppet theater. In addition to puppet design, Efimov was noted for his book illustration and sculpture. He created pieces for the Central Museum of Ethnology, the North River Terminal, several metro and railway stations and the Grand Kremlin Palace. Internationally his sculptures were awarded gold medals in 1937 at the Paris World Exhibition and in Russia he was honored as both an Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and the People’s Artist of the RSFSR.

Ivan Efimov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Иван Семёнович Ефимов 11 February 1878 Moscow, Russia |

| Died | 7 January 1959 (aged 80) Moscow, USSR |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation | sculptor, puppeteer |

| Years active | 1918-1958 |

| Known for | animal sculptures |

Early life

Ivan Semyonovich Efimov was born on 11 February 1878 in Moscow.[1] His father, Semyon Grigorievich Efimov, was a government official and the illegitimate son of a Ukrainian peasant woman.[1][2][3] His mother descended from the Demidov family of whom the forebear, Nikita Demidov, a blacksmith from Tula, pioneered the production of iron ore in the Ural Mountains.[3] Efimov grew up in an aristocratic milieu in the Tambov province on an estate known as "Otradnoe", to which later he would take his young bride.[2][3] At a young age, he was sent to a military school, which had a profound effect on him. He felt imprisoned and cut off from nature, which led to his creating handcrafted toy animals.[4]

In 1896, Efimov completed his studies at the Polivanov Gymnasium, which had been founded by Lev I. Polivanov,[5] and then took private art lessons with Nikolai A. Martynov for two years.[1] Between 1898 and 1901, he studied natural science at Moscow University, simultaneously taking painting courses under Valentin Serov and sculpture classes with Anna Golubkina at the art school founded by Elizaveta Nikolaevna Zvantseva.[1][5] Between 1905 and 1908 he worked in Abramtsevo Colony in the ceramic workshop of Savva Mamontov creating toys, while continuing his studies at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (Russian: Московское училище живописи, ваяния и зодчества (МУЖВЗ)) with Serov, and studying sculpture with Sergei Volnukhin.[1] In April 1906, he married fellow student and Serov's cousin, Nina Yakovlevna Simonovicha[6] and in 1909 the couple took a break from their studies at the Moscow School and went to Paris.[7]

Between 1909 and 1911, Efimov worked in the studio of Antoine Bourdelle[5] and beginning in 1910 studied sculpture with Filippo Colarossi and mastered the art of etching under the direction of Elizaveta Kruglikova. He joined the circle of Russian artists working in Montparnasse and took inspiration from nature at the Paris Menagerie.[1] In 1911, the couple briefly returned to Moscow, where Simonovich-Efimova completed her studies at the Moscow School before they moved to Lipetsk in 1912, spending several months on the Efimov family estate.[7][8] By the end of the year, they were back in Moscow and Efimov had returned to his studies at the Moscow School. He graduated with the title of sculptor in 1913 with his presentation pieces, Bison and Passion[1] and almost immediately went into service in World War I.[1][5]

Career

After the October Revolution, Efimov was hired to teach at the Second State Free Art Studio in 1918, continuing his affiliation with the school when it was replaced by the Higher Art and Technical Studios until 1930. In 1918, he joined his wife in organizing a puppet theater in Moscow and together with her created puppets, costumes and scenery for their mobile theater, which operated until 1943. Some of his most known works were for their productions of Hans Christian Andersen's The Princess and the Pea (1918) and Shakespeare's Macbeth (1921).[1][9] They created the first professional puppet theater in Russia and utilized innovative techniques with rods. The pair also worked in shadow theaters using the art of silhouettes.[10]

For his own sculptures, Efimov preferred to depict the essence of animals. He was not interested in their portraiture, but rather in capturing the typical characteristics of his subject. He also rejected traditional media like marble and stone, preferring to work with cement, clay, glass, metal or wood, which placed his works in the folk art tradition.[10] He tried to capture the natural movement as well as characteristics. His sculptures "Ostrich" (1935) forged from copper with spiraling copper plumes and "Ram" (1938) made with loose curls of copper wire crowned by tightly spiraled wire horns, exemplify his works.[9] Placing them in habitat was also important for Efimov, employing various techniques, as in his copper sculpture "Fish". The fish is attached via a wire to a copper sheet in the shape of a water lily, which in turn is perched on a three-dimensional piece of glass, representing water.[10]

Efimov also worked on book illustrations, in such works as The Cat, the Goat and the Ram (Russian: Кот, козел да баран, 1924), Aesop's Fables (Russian: Басни Эзоп, 1925), How the Animal Cart Awoke (Russian: Как машина зверей всполошила, 1927), Mena (Russian: Мена, 1929) and Mordovian epic (Russian: Мордовский эпос, 1930). In the early 1930s, he participated in anthropological studies of Bashkiria and Udmurtia for the Central Museum of Ethnology (Russian: Центральный музей народоведения),[1] which in the early 1930s was located at the Mamonov dacha adjacent to the Vorobiev Palace.[11] Thereafter, Efimov worked from 1932 to 1933 to create an installation, "History of Russia in Mannequins" for the same museum.[5] Between 1935 and 1937, he sculpted a fountain, "Dolphins" for the North River Terminal[1] and between 1936 and 1937 created the sculpture "Old and New Moscow" for Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure.[5] In 1937 two of his sculptures, "Fisherman with Fish" and "Bull" received the gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris.[1]

Efimov designed reliefs for two of the Moscow metro stations, Paveletskaya and Avtozavodskaya (1942-1943); two of the Moscow railway stations, Yaroslavl (1946-1947) and Leningrad (1948); and for the winter garden at the Grand Kremlin Palace (1952). In 1955 he was designated as an Honored Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and three years later, in 1958, Efimov was honored as the People’s Artist of the RSFSR.[1]

Death and legacy

Efimov died on 7 January 1959 in Moscow. He has works in the permanent collections of the Pushkin Museum, the State Museum of Ceramics at the "XVIII Century Manor of Kuskovo", the State Russian Museum, and the State Tretyakov Gallery. Posthumous exhibitions of his work were held in Moscow and Leningrad between 1959 and 1960, in Moscow in 1970, and in Kaluga, Obninsk, and Moscow in 1975.[1]

References

Citations

- Maslovka 2007.

- State Archive of the Lipetsk Region 2008.

- Ковычева 2014, p. 112.

- Ковычева 2014, pp. 111-112.

- Шмидт 2013.

- Posner 2012, p. 131.

- Posner 2012, p. 121.

- Lipetsk Regional Universal Scientific Library 2013.

- Грачев 2005.

- The Art Calendar of 100 Memorable Dates 1978.

- Лебедева 2015.

Bibliography

- Грачев (Grachev), Сергей (Sergey) (2005). "Ефимов, Иван Семенович". Artonline Encyclopedia (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Ковычева (Kovycheva), Елена Ивановна (Elena Ivanovna) (2014). "Условия Формирования Творческой Личности Художника-Реалиста Серебряного Века (На Примере Н. Я. Симонович-Ефимовой И И. С. Ефимова)" [Conditions for the Formation of the Creative Personality of the Artist-Realist of the Silver Age (On the Example of N. Ya. Simonovich-Efimova and I. S. Efimov)] (PDF). Исторические, философские, политические и юридические науки, культурология и искусствоведение. Вопросы теории и практики (Historical, philosophical, political and legal sciences, cultural studies and art history. Issues of theory and practice) (in Russian). Tambov, Russia: Издательства Грамота. 41 (3). ISSN 1997-292X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Лебедева (Lebedeva), Ольга (Olga) (2015). "Центральный музей народоведения" [Central Museum of Ethnology]. Топография террора (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: International Society "Memorial". Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- Posner, Dassia N. (2012). "Sculpture in Motion: Nina Simonovich-Efimova and the Petrushka Theatre". In Fryer, Paul (ed.). Women in the Arts in the Belle Epoque: Essays on Influential Artists, Writers and Performers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 118–135. ISBN 978-0-7864-6075-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Шмидт (Schmidt), С. О. (S. O.), ed. (2013). "Ефимовы, супруги, художники. Одни из создателей отеч. профес. т-ра кукол" [Efimov, spouses, artists. Some of the creators of the fatherland. Prof. T-ra of dolls]. Лица Москвы Энциклопедия (Faces of Moscow Encyclopedia) (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: The government of Moscow by Moscow Textbooks and Carto-lithography. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "И. С. Ефимов (1873—1959)". Художественный календарь 100 памятных дат [The Art Calendar of 100 Memorable Dates] (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: Советский художник. 1978. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016 – via Детский сад.Ру (Kindergarten.ru).

- "Ефимов Иван Семенович 1878-1959" [Efimov, Ivan Semyonovich 1878-1959]. Maslovka (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: Tretyakovskaya Gallery. 21 April 2007. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "Ефимов Иван Семенович К 130-летию со дня рождения" [Efimov, Ivan Semyonovich on the occasion of the 130th anniversary of his birth]. Galo.admlr.lipetsk.ru (in Russian). Lipetsk, Russia: State Archive of the Lipetsk Region. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "Симонович-Ефимова, Нина Яковлевна (1877-1948)" [Simonovich-Efimova, Nina Yakovlevna (1877-1948)]. Лоунб.ru (in Russian). Lipetsk, Russia: Липецкая областная универсальная научная библиотека (Lipetsk Regional Universal Scientific Library). 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.