Italian submarine Berillo

Italian submarine Berillo was a Perla-class submarine built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) during the 1930s. It was named after a gemstone Beryl.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Berillo |

| Namesake: | Beryl |

| Builder: | CRDA, Monfalcone |

| Laid down: | 14 September 1935 |

| Launched: | 14 June 1936 |

| Commissioned: | 5 August 1936 |

| Fate: | Scuttled, 2 October 1940 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Perla-class submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 60.18 m (197 ft 5 in) |

| Beam: | 6.454 m (21 ft 2.1 in) |

| Draft: | 4.709 m (15 ft 5.4 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Range: |

|

| Test depth: | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Complement: | 44 (4 officers and 40 NCOs and sailors) |

| Armament: |

|

Design and description

The Perla-class submarines were essentially repeats of the preceding Sirena class. They displaced 680 metric tons (670 long tons) surfaced and 844 metric tons (831 long tons) submerged. The submarines were 60.18 meters (197 ft 5 in) long, had a beam of 6.45 meters (21 ft 2 in) and a draft of 4.7 meters (15 ft 5 in).[1]

For surface running, the boats were powered by two 600-brake-horsepower (447 kW) diesel engines, each driving one propeller shaft. When submerged each propeller was driven by a 400-horsepower (298 kW) electric motor. They could reach 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) on the surface and 7.5 knots (13.9 km/h; 8.6 mph) underwater. On the surface, the Perla class had a range of 5,200 nautical miles (9,600 km; 6,000 mi) at 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), submerged, they had a range of 74 nmi (137 km; 85 mi) at 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph).[2]

The boats were armed with six internal 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes, four in the bow and two in the stern. One reload torpedo was carried for each tube, for a total of twelve. They were also armed with one 100 mm (3.9 in) deck gun for combat on the surface. The light anti-aircraft armament consisted of one or two pairs of 13.2-millimeter (0.52 in) machine guns.[1]

Construction and career

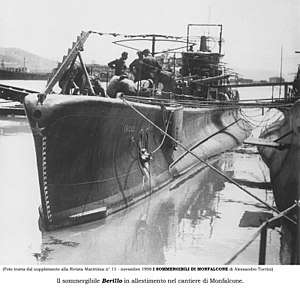

Berillo was built by CRDA at their shipyard in Monfalcone, laid down on 14 September 1935, launched on 14 June 1936 and completed on 5 August 1936.[3]

After entering service, the submarine was assigned to the 35th Squadron based at Messina but relocated to Augusta.[4] During 1936 Berillo underwent an intensive endurance training cruise in the central Mediterranean, sailing between Tobruk, Benghazi, Marsa el Hilal, Bardia, Leros and Naples.

During January through September 1937 she participated in the Spanish Civil War, carrying out three missions. On 1 January Berillo left Naples under command of Captain Vittorio Prato for the first mission to be carried out off Cartagena. She returned to the base on 17 or 18 January without any sightings. On 5 August Berillo left from Augusta, under command of captain Andrea Gasparini, for the second mission to patrol an area northwest of Pantelleria, between Cape Lilibeo and Cape Bon. She remained on station for eleven days during which there were 45 sightings and attack attempts. On 14 August[4] she fired two torpedo at a steamer, but missed.[5] Two days later she returned to the base.[4] On 28 August Berillo set off on her third mission this time again off Cartagena. On 6 September she returned to the base without sighting any suspicious ships.

In 1938 Berillo was transferred together with Iride and Onice to the Red Sea base at Massawa in Eritrea.[4]

In spring of 1939 she returned to the Mediterranean base at Taranto but subsequently transferred to Augusta.[4]

In January of 1940 Captain Camillo Milesi Ferretti assumed command of Berillo.

At the time of Italy's entrance into World War II, Berillo, together with Gemma and Onice, was assigned the 13th Squadron (I Submarine group) based at La Spezia, operating from Augusta. Early in the war, she performed missions in the central Mediterranean without encountering enemy ships.[4]

On 13 July 1940 she was deployed along with the largest submarines Morosini, Nani and Comandante Faà di Bruno to an area east of Gibraltar. She did not encounter any enemy ships. In a subsequent mission she was sent to patrol an area off Malta, but again she did not encounter any enemy traffic.

On 18 September 1940 Berillo was ordered to patrol off Sidi Barrani and Marsa Matruh in support of the Italian offensive in Egypt. During her trip to the area of operation, Berillo was plagued by a number of breakdowns. First her stern pump went off, but was fixed quickly. Then her aft hydroplanes went out of order, which were fixed but her steering was left rather impaired. On 25 September Berillo reached her patrol area, north of Ras Ultima.

Two days went by without any sightings. In the evening of 27 September, after surfacing, Berillo suffered another breakdown – her diesel engines suddenly died while she was sailing on the surface. Despite the crew's effort, they could only partially restart port side engine. For the next two days Berillo continued moving using electric engines and trying to repair her diesel ones but unsuccessfully. At 21:30 on 29 September, Berillo received a radio message informing her about a scattered enemy battle group that was detected nearby consisting of a battleship, an aircraft carrier, five cruisers and nineteen destroyers. Obviously the submarine could not possibly pass on such a juicy target, and even though moving at the exasperatingly low speed of 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph), Berillo managed to reach her new assigned sector off Sidi Barrani, about 60 miles (97 km) further north than the previous sector, at 07:00 on 30 September. In the evening of 30 September when the submarine surfaced, the starboard engine finally came back to life. At dawn on 1 October, the submarine submerged again, and remained at the periscope depth for the rest of the day. Once again, no enemy ships were sighted. That evening, Berillo surfaced again to charge the batteries and to replenish air supply. When she tried to start her diesels again, one of the oil pumps failed. The crew spent the night fixing it, as well as working on the port-side engine, which was malfunctioning again.

At about 03:00, enemy ships were finally spotted. The destroyers HMS Havock and HMS Hasty were approximately 6,000 meters (6,600 yd) away, returning to Piraeus after escorting Convoy AN-4. While remaining on the surface, Captain Milesi Ferretti continued his approach towards enemy ships. The speed of the closest ship was estimated at about 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph).[6]

Berillo continued closing in until she was about 800 meters (870 yd) away. The captain ordered a torpedo attack, but torpedo electric launches failed this time, so the crew had to do a manual launch.[4] Time went by, but there were no explosion as the target was apparently missed, but the enemy destroyer detected the attack. As the distance shortened to 600 meters (660 yd), Ferretti ordered two more torpedoes fired but they missed their intended target again, with one of them going just under one of the destroyers without exploding.[7]. He then ordered hard to starboard to launch from the stern tubes, but at this point, the British ships simultaneously illuminated Berillo with four searchlights, and at the same time fired from their guns. While their shots missed the submarine, they forced her to abandon the attack. Ferretti ordered a crash dive as one of the destroyers accelerated towards the submarine with a clear intent to ram her.[6] Berillo went to about 90 meters (300 ft) in 32 seconds, and the depth charge attacks commenced, knocking out her electricals, intercom system, pressure gauges and diving planes.[6] The submarine started experiencing problems with buoyancy, falling down to 135 meters (443 ft), and then rising to 40 meters (130 ft) after some compressed air was blown.[4][6] The next set of attacks damaged and knocked out the engines, propellers, started a fire in the aft compartment and opened water leaks in the hull. The submarine continued her up-and-down swings between 50 and 100 meters (160 and 330 ft), sometimes sinking to 120–130 meters (390–430 ft).[6] Another attack sent Berillo sinking even deeper, 170 meters (560 ft) or perhaps even more.[8] The captain ordered to blow all air to try to save the submarine and her crew, and Berillo started slowly rising and eventually at 05:30 on 2 October, she flew out of the water with a list of 45°.[7][6] Two crewmen were sent to open the hatches, but they were all jammed due to the damage suffered by the hull. British destroyers meanwhile wasted no time in opening fire on the surfaced submarine. One of the shots knocked out the deck gun, and the other one penetrated the conning tower, killing two crewmen who were trying to open the hatch. In the process, the shell dislodged the hatch and the rest of the crew was able to abandon ship. As everyone left the submarine, she sank in the approximate position 33°09′N 26°24′E about 120 nautical miles (220 km) north of Sidi Barrani.[9]

Notes

- Chesneau, p. 309

- Bagnasco, p. 154

- Pollina, pp. 152–53

- Berillo at Monfalcone Naval Museum

- Frank, p. 96

- "Memoirs of Captain Milesi". Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- Giorgerini, p. 245

- "Final Mission of Berillo". Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- Rohwer, p. 43

References

- Bagnasco, Erminio (1977). Submarines of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-962-6.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Frank, Willard C., Jr. (1989). "Question 12/88". Warship International. XXVI (1): 95–97. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Giorgerini, Giorgio (2002). Uomini sul fondo. Storia del sommergibilismo italiano dalle origini ad oggi (Second ed.). Mondadori. ISBN 8804505370.

- Pollina, Paolo (1963). I Sommergibili Italiani 1895–1962. Rome, Italy: SMM.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.