Italian cruiser Pisa

The Italian cruiser Pisa was the name ship of her class of two armored cruisers built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) in the first decade of the 20th century. The ship participated in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912, during which she supported the occupations of Tobruk, Libya and several islands in the Dodecanese and bombarded the fortifications defending the entrance to the Dardanelles. During World War I, Pisa's activities were limited by the threat of Austro-Hungarian submarines, although the ship did participate in the bombardment of Durazzo, Albania in late 1918. After the war she became a training ship and was stricken from the Navy List in 1937 before being scrapped.

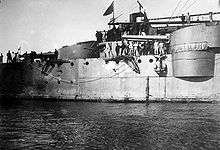

Pisa, February 1932 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Pisa |

| Namesake: | Pisa |

| Builder: | Cantiere navale fratelli Orlando, Livorno |

| Laid down: | 20 February 1905 |

| Launched: | 15 September 1907 |

| Completed: | 1 September 1909 |

| Decommissioned: | 28 April 1937 |

| Reclassified: | Coastal battleship, 1 July 1921 |

| Fate: | Scrapped |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Pisa-class armored cruiser |

| Displacement: | 9,832 t (9,677 long tons) |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 21 m (68 ft 11 in) |

| Draft: | 7.1 m (23 ft 4 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Endurance: | 2,500 nmi (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Design and description

Pisa had a length between perpendiculars of 130 meters (426 ft 6 in) and an overall length of 140.5 meters (460 ft 11 in). She had a beam of 21 meters (68 ft 11 in) and a draft of 7.1 meters (23 ft 4 in). The ship displaced 9,832 metric tons (9,677 long tons) at normal load, and 10,600 metric tons (10,400 long tons) at deep load.[1] The Pisa-class ships had a complement of 32 officers and 652 to 655 enlisted men.[2]

The ship was powered by two vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one propeller shaft using steam supplied by 22 Belleville boilers. Designed for a maximum output of 20,000 indicated horsepower (15,000 kW) and a speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph),[3] Pisa handily exceeded this, reaching a speed of 23.47 knots (43.47 km/h; 27.01 mph) during her sea trials from 20,808 ihp (15,517 kW). She had a cruising range of about 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[1]

The main armament of the Pisa-class ships consisted of four Cannone da 254/45 V Modello 1906 guns in twin-gun turrets fore and aft of the superstructure. The ships mounted eight Cannone da 190/45 V Modello 1906 in four twin-gun turrets, two in each side amidships, as their secondary armament. For defense against torpedo boats, the ships carried 16 quick-firing (QF) Cannone da 76/50 V Modello 1908 guns and eight QF Cannone da 47/40 V Modello 1908 guns. They were also equipped with three submerged 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. During World War I, her 76 and 47 mm guns were replaced by twenty 76/40 guns; six of these were anti-aircraft guns.[1]

Pisa was protected by an armored belt that was 200 mm (7.9 in) thick amidships and reduced to 90 mm (3.5 in) at the bow and stern.[3] The armored deck was 51 mm (2.0 in) thick. The conning tower armor was 180 mm (7.1 in) thick. The 254 mm gun turrets were protected by 160 mm (6.3 in) of armour while the 190 mm turrets had 140 mm (5.5 in).[2]

Construction and career

Pisa, named after the eponymous city,[4] was laid down on 20 February 1905 at the Orlando shipyard in Livorno.[2] The ship was launched on 15 September 1907 and completed on 1 September 1909.[1][4]

When the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912 began on 29 September 1911, Pisa was the flagship of Rear-Admiral Ernesto Presbitero, commander of the 2nd Division of the 1st Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet. Pisa and her sister ship, Amalfi, were among the ships selected for the initial blockade of Tripoli. On 2 October, the Training Division relieved the 1st Squadron in blockade duty, allowing them to join the main Italian fleet.[5]

After a fruitless search for the main Ottoman fleet and the peaceful occupation of Tobruk,[6] Pisa, Amalfi, and the battleship Napoli were joined by the recently commissioned armored cruiser San Marco, three destroyers, and two torpedo boats. The group escorted several Italian transports that arrived off Derna on 15 October. After negotiations for a surrender of the town fell apart, Pisa shelled the barracks and a fort. There was no return fire from Derna, so a boat with offers of a truce was sent in. When it was greeted by a volley of rifle fire, Pisa and the other armored cruisers opened fire on the town with their 190 mm guns and, according to a contemporary account, "completely destroyed" the town in 30 minutes time.[7] A landing party was unable to reach the shore because of rough seas and gunfire from the shore. Pisa and her consorts then shelled the beach for two hours. Weather conditions prevented a landing until the 18th, when 1,500 men took possession of Derna.[7]

Pisa remained in North African waters until mid-December when most of the 1st Squadron returned to Italy. Pisa later escorted several troop transports from Augusta, Sicily in an attempt to seize the port of Zuara shortly before Christmas that was foiled by bad weather.[8] In mid-April 1912 the Italian fleet sortied into the eastern Aegean Sea with Pisa and Amalfi leading in an attempt to lure out the Ottoman fleet. When that failed, the Italians bombarded the fortifications defending the Dardanelles to little effect before the main body departed for Italy on the 19th. Pisa, Amalfi, and an assortment of smaller craft were left behind, however, to continue destroying telegraph and radio stations and cutting underwater cables. Sailors from the two cruisers captured the island of Astropalia on 28 April to allow Italian forces to use it as supply base.[9] A week later, the ship supported the occupation of Rhodes on 4 May. Pisa returned to Italy in September, but after the war ended she spent the first half of 1913 in Constantinople and the Aegean before returning to Taranto on 24 June.[10]

The ship was based at Brindisi when Italy declared war on the Central Powers on 23 May 1915. That night, the Austro-Hungarian Navy bombarded the Italian coast in an attempt to disrupt the Italian mobilization. Of the many targets, Ancona was hardest hit, with disruptions to the town's gas, electric, and telephone service; the city's stockpiles of coal and oil were left in flames. All of the Austrian ships safely returned to port, putting pressure on the Regia Marina to stop the attacks. When the Austrians resumed bombardments on the Italian coast in mid-June, Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel responded by sending Pisa and the other armored cruisers at Brindisi—the navy's newest—to Venice to supplement the older ships already there.[11] Shortly after their arrival at Venice, Amalfi was sunk by a submarine on 7 July and her loss severely restricted the activities of the other ships based at Venice.[12] Pisa was transferred to Vlore, Albania in April 1916[10] and participated in the bombardment of Durazzo on 2 October 1918 which sank one merchantman and damaged two others.[13]

On 1 July 1921, Pisa was reclassified from a second-class battleship to a coastal battleship and became a training ship. In 1925 she was modified to operate a Macchi M.7 flying boat. From 1925 to 1930, the ship was used to train naval cadets and lieutenants. Pisa was stricken on 28 April 1937 and subsequently broken up.[1]

Notes

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 261

- Fraccaroli, p. 32

- Silverstone, p. 290

- Silverstone, p. 302

- Beehler, pp. 9, 19

- Stephenson, pp. 115–116

- Beehler, p. 30

- Beehler, pp. 47, 50, 53

- Beehler, pp. 67–68, 71; Stephenson, pp. 262–265

- Marchese

- Sondhaus, pp. 274–276, 279

- Halpern, pp. 148, 151; Sondhaus, p. 289

- Halpern, p. 176

Bibliography

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War, Sept. 29, 1911 to Oct. 18, 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Advertiser-Republican. OCLC 63576798.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0105-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Halpern, Paul S. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Marchese, Giuseppe (February 1996). "La Posta Militare della Marina Italiana 8^ puntata". La Posta Militare (in Italian) (72). Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9. OCLC 59919233.

- Stephenson, Charles (2014). A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War 1911–1912: The First Land, Sea and Air War. Ticehurst, UK: Tattered Flag Press. ISBN 978-0-9576892-7-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pisa (ship, 1909). |