San Giorgio-class cruiser

The San Giorgio class consisted of two armored cruisers built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) in the first decade of the 20th century. The second ship, San Marco, was used to evaluate recently invented steam turbines in a large ship and incorporated a number of other technological advances. The ships participated in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912, although San Giorgio was under repair for most of the war. San Marco supported ground forces in Libya with naval gunfire and helped them to occupy towns in Libya and islands in the Dodecanese. During World War I, the ships' activities were limited by the threat of Austro-Hungarian submarines, although they did bombard Durazzo, Albania in 1918.

San Marco underway, 18 August 1910 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | San Giorgio |

| Builders: | Regio Cantieri di Castellammare di Stabia, Castellammare di Stabia |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Pisa class |

| Succeeded by: | None |

| Built: | 1905–1911 |

| In service: | 1910–1943 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Lost: | 1 |

| Scrapped: | 1 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement: | 10,167–10,969 t (10,006–10,796 long tons) |

| Length: | 140.89 m (462 ft 3 in) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 21.03 m (69 ft 0 in) |

| Draft: | 7.35–7.76 m (24 ft 1 in–25 ft 6 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Range: | 4,800–6,270 nmi (8,890–11,610 km; 5,520–7,220 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 32 officers, 666–73 enlisted men |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

San Giorgio spent several years in the Far East and Italian Somaliland after the war and became a training ship in 1931. After a brief deployment to Spain in 1936, she was reconstructed to better serve her role as a training ship. The ship's anti-aircraft armament was augmented when she was deployed to Tobruk, Libya to reinforce the port's defenses after Italy declared war on Britain in May 1940. San Giorgio was scuttled in early 1941 when Allied forces were poised to capture the port. Her wreck was salvaged in 1952, but sank while under tow. San Marco was converted into a target ship in the early 1930s and was found sunk at the end of the war. She was scrapped in 1949.

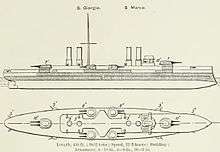

Design and description

The San Giorgio class was ordered almost immediately after the preceding Pisa-class ships, and was an improved version of that design. The forecastle was extended to improve seaworthiness, turret armor was increased, habitability was improved and the propulsion machinery was redistributed. San Marco was given the first steam turbines fitted in a large Italian ship for comparative purposes with San Giorgio, which retained the traditional vertical triple-expansion steam engines (VTE). San Marco was a very innovative ship as she was the first turbine-powered ship in any navy to have four propeller shafts, the first with a gyroscopic compass, the first with antiroll tanks, and the first not to use wood in any way.[1]

The San Giorgio-class ships had a length between perpendiculars of 131.04 meters (429 ft 11 in) and an overall length of 140.89 meters (462 ft 3 in). They had a beam of 21.03 meters (69 ft 0 in) and a draft of 7.35–7.76 meters (24 ft 1 in–25 ft 6 in). The ships displaced 10,167–10,969 metric tons (10,006–10,796 long tons) at normal load, and 11,300–11,900 metric tons (11,100–11,700 long tons) at deep load. The ships had a complement of 32 officers and 666 to 673 enlisted men.[2]

Propulsion

The machinery installation of this class was changed in comparison to that of the Pisa class, with the engines amidships with the 14 mixed-firing water-tube boilers fore and aft of the engines. Their exhausts were trunked together into two widely spaced pairs of funnels. Designed for a maximum speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph),[3] the two ships were given different types of propulsion machinery for evaluation. San Giorgio's two shafts, pair of 19,500-indicated-horsepower (14,500 kW) VTE steam engines and Blechynden boilers differed only slightly from those used by the Pisas. In contrast, San Marco's four shafts, each driven by a license-built Parsons steam turbine, was a first for the Regia Marina. The turbines used steam provided by Babcock & Wilcox boilers at a working pressure of 210 psi (1,448 kPa; 15 kgf/cm2)[4] to reach their designed output of 23,000 shp (17,000 kW). Both ships exceeded their designed speeds, with San Giorgio reaching 23.2 knots (43.0 km/h; 26.7 mph) and San Marco 23.75 knots (43.99 km/h; 27.33 mph) during their sea trials. The biggest difference between the sisters was that the turbines of San Marco proved to be significantly less economical in service (a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) and 2,480 nautical miles (4,590 km; 2,850 mi) at 21.25 knots (39.36 km/h; 24.45 mph)) compared to San Giorgio's VTE steam engines (6,270 nautical miles (11,610 km; 7,220 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) and 2,640 nautical miles (4,890 km; 3,040 mi) at 21.25 knots (39.36 km/h; 24.45 mph).[5]

Armament

The main armament of the San Giorgio-class ships consisted of four Cannone da 254/45 A Modello 1907[Note 1] guns in electrically powered, twin-gun turrets fore and aft of the superstructure.[5] The turrets had an arc of fire of 260°.[4] The 254 mm (10.0 in) gun fired 204.1–226.8-kilogram (450–500 lb) armor-piercing (AP) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 870 meters per second (2,850 ft/s). At maximum elevation of +25°, the guns had a range of about 25,000 meters (27,000 yd).[6] The ships mounted eight Cannone da 190/45 A Modello 1908 in four electrically powered twin-gun turrets, two in each side amidships, as their secondary armament. Their arc of fire was 160°.[4] These Armstrong Whitworth 190 mm (7.5 in) guns fired 90.9-kilogram (200 lb) AP shells at 864–892 m/s (2,835–2,927 ft/s). At maximum elevation of +25°, the guns had a range of about 22,000 meters (24,000 yd).[7]

For defense against torpedo boats, the San Giorgios mounted 18 quick-firing (QF) 40-caliber 76 mm (3.0 in) guns. Eight of these were mounted in embrasures in the sides of the hull and the rest in the superstructure.[5] The ships were also fitted with a pair of QF 40-caliber 47 mm (1.9 in) guns. The San Giorgio-class ships were equipped with three submerged 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. During World War I, eight of the 76 mm guns were replaced by six 76 mm anti-aircraft (AA) guns[5] and one torpedo tube was removed.[3]

Protection

The ships were protected by an armored belt that was 200 mm (7.9 in) thick amidships and reduced to 80 mm (3.1 in) at the bow and stern.[3] The belt was 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) high, of which 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) was below the waterline.[4] The armored deck was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick and the conning tower armor was 254 mm thick. The 254 mm gun turrets were protected by 200 mm of armour while the 190 mm turrets had 160 mm (6.3 in).[5]

Ships

| Name | Builder[2] | Laid down[5] | Launched[5] | Completed[5] | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Giorgio | Regio Cantieri di Castellammare di Stabia, Castellammare di Stabia | 4 July 1905 | 27 July 1908 | 1 July 1910 | Scuttled, 22 January 1941; Sank under tow, 1952[8] |

| San Marco | 2 January 1907 | 20 December 1908 | 7 February 1911 | Sunk, 1945; Scrapped, 1949[9] |

Service

_stranded_1913.jpg)

San Giorgio ran aground in August 1911 off Naples-Posillipo;[10] heavily damaged, she was under repair until June 1912, missing most of the Italo-Turkish War. San Marco supported the occupations of Benghazi and Derna, Libya during the war and bombarded the fortifications defending the entrance to the Dardanelles.[11] She also supported the forces occupying the island of Rhodes in May 1912. In February 1913, San Giorgio cruised the Aegean Sea and made a port visit to Salonica, Greece, the next month.[12] She ran aground again on 21 November in the Strait of Messina, but was only slightly damaged.[8]

During World War I, the activities of the ships were restricted by the threat of submarine attack after the armored cruisers Giuseppe Garibaldi and Amalfi were sunk by submarines shortly after Italy joined the war in May 1915, although the ships did participate in the bombardment of Durazzo, Albania in late 1918.[13]

After the war, San Giorgio was deployed to the Far East[14] while San Marcos played a minor role in the Corfu incident in 1923.[15][16] San Giorgio, escorted by San Marco, ferried Crown Prince Umberto to South America in July–September 1924,[17][18] and then supported operations in Italian Somaliland in 1925–1926.[14] The ship was disarmed and converted into a radio-controlled target ship in 1931–1935; her old boilers were replaced by four oil-burning ones which reduced her maximum speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). She was captured by the Germans when they occupied La Spezia on 9 September 1943; San Marcos was found at the end of the war half-sunk in the harbor there and was broken up in 1949.[9]

From 1930 to 1935, San Giorgio was based in Pola as a training ship, and was sent to Spain after the Spanish Civil War began in 1936 to protect Italian interests.[14] In 1937–1938 she was reconstructed to serve as a dedicated training ship for naval cadets at the Arsenale di La Spezia: six boilers were removed and the remaining eight were converted to burn fuel oil which reduced her speed to 16–17 knots (30–31 km/h; 18–20 mph). Each pair of funnels was trunked together and her 76/40 guns were replaced by 100 mm (4 in) / 47 caliber guns in four twin turrets abreast the funnels. Her torpedo tubes were also removed while she received a light AA suite for the first time, with the addition of six Breda 37 mm (1.5 in) 54-cal. guns, a dozen 20 mm (0.79 in) Breda Model 35 autocannon and four 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Breda Model 31 machine guns in two twin mounts.[9][19]

Prior to her being sent to reinforce the defenses of Tobruk in early May 1940, a fifth 100/47 gun turret was added on the forecastle and five more twin 13.2 mm (0.52 in) machine gun mounts were added to better suit her new role as a floating battery.[19] Two days after Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June, the British light cruisers Gloucester and Southampton bombarded Tobruk and attacked San Giorgio, which was not hit during the engagement.[20] A British submarine fired two torpedoes at San Giorgio on 19 June, but these detonated before reaching the ship.[21] The ship's guns engaged Allied aircraft attacking Tobruk many times, destroying several. She was scuttled in shallow water on 22 January 1941 to prevent her capture during the Battle of Tobruk.[19] San Giorgio was awarded the Gold Medal of Military Valour (Medaglia d'Oro al Valore Militare) for her performance at Tobruk.[22] Her wreck was refloated in 1952, but sank under tow en route to Italy.[19]

Footnotes

- The /45 denotes the length of the gun barrels; in this case, the gun is 45 caliber, meaning that the gun is 45 times long as it is in diameter.

References

Notes

- Gardiner & Gray, pp. 252, 261

- Fraccaroli, p. 33

- Silverstone, p. 290

- Attilio, p. 477

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 261

- Campbell, p. 324; Friedman, pp. 68, 238

- Campbell, p. 329; Friedman, pp. 79, 239

- Silverstone, p. 305

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 262

- "Stranded Italian Cruiser". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 9 September 1911. p. 6. Retrieved 28 February 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Beehler, pp. 30, 49, 84; Stephenson, pp. 217, 262–265

- Marchese

- Halpern, pp. 148, 151, 176; Sondhaus, p. 289

- Sicurezza, p. 46

- "Greek Reparations: Evacuation of Corfu Begun". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 22 September 1923. p. 9. Retrieved 1 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Italy and Greece: Indemnity Paid Over". Gloucestershire Echo. 1 October 1923. p. 2. Retrieved 1 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Prince Humbert Sails". The New York Times. 2 July 1924. p. 31.

- "Humbert Sails Home from Brazil". The New York Times. 20 September 1924. p. 22.

- Brescia, p. 104

- Rohwer, p. 28

- "HMS Parthian (N 75)". uboat.net. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- San Giorgio

Bibliography

- Attilio, Dagnino (December 1911). "Italy's First Turbine-Driven Cruiser, the San Marco". International Marine Engineering. 16: 477–480.

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0105-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Halpern, Paul S. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Marchese, Giuseppe (February 1996). "La Posta Militare della Marina Italiana 8^ puntata". La Posta Militare (in Italian) (72).

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- "San Giorgio: Incrociatore corazzato". Storia e Cultura: La nostra Storia: Almanacco storico navale (in Italian). Marina Militare. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Sicurezza, Renato. "Il Regio Incrociatore Corazzato San Giorgio". Yacht World (in Italian). Milan: Scode: 44–47. ISSN 0394-3143.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9. OCLC 59919233.

- Stephenson, Charles (2014). A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War 1911–1912: The First Land, Sea and Air War. Ticehurst, UK: Tattered Flag Press. ISBN 978-0-9576892-7-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Giorgio class cruiser. |