Ishkashimi language

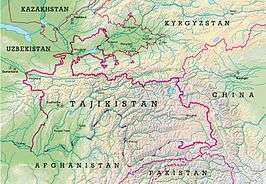

Ishkashimi (Ishkashimi: škošmī zəvuk/rənīzəvuk) [3] is an Iranian language spoken predominantly in the Badakhshan Province in Afghanistan and in Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region in Tajikistan.[4]

| Ishkashimi | |

|---|---|

| škošmi zəvůk | |

| Native to | Afghanistan, Tajikistan |

Native speakers | 3,000 (2009)[1] |

| None | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | isk |

| Glottolog | ishk1244[2] |

| Linguasphere | 58-ABD-db |

The total number of speakers is c. 2,500, most of whom are now dispersed throughout Tajikistan and Afghanistan and small villages within the vicinity. Based on this number, Ishkashimi is threatened to becoming critically endangered or extinct in the next 100 years whereas other significant languages are being spoken in schools, homes, etc. These languages are the Tajik language in Tajikistan and the Dari language in Afghanistan, and they are contributing to the decline in the use of Ishkashimi, which at the moment has a status of endangered language. Besides, information about Ishkashimi language is limited due to the lack of extensive and systematic research and the lack of a written system.[5]

Ishkashimi is closely related to Zebaki and Sanglechi dialects (in Afghanistan). It was grouped until recently with the Sanglechi dialect under the parent family Sanglechi-Ishkashimi (sgl), but a more comprehensive linguistic analysis showed significant differences between these speech varieties.[6] Phonology and grammar of Ishkashimi language is similar to phonology and grammar of the closely related Zebaki dialect.[7]

Geographic distribution

Ishkashimi language has approximately 2500 speakers, of which 1500 speakers are in the Ishkashim and Wakhan districts and a variety of villages in the Badakhshan Province in Afghanistan, and 1000 speakers are in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region in Tajikistan, particularly in Ishkoshim town and neighboring Ryn and Sumjin villages.[4][8]

Classification

Ishkashimi is an Iranian language of the Indo-European family.[6] Originally Ishkashimi was considered to belong to the Sanglechi-Ishkashimi family of Eastern Iranian languages. But recent research showed that such a combination was inappropriate for these dialects due to the significant linguistic differences between them. And on January 18, 2010 the parent language had retired and been split into what are now Sanglechi and Ishkashimi dialects.[6] This subfamily has furthermore been considered a part of the Pamir languages group, together with the Wakhi language, and of the subgroup comprising Shughni, Rushani, Sarikoli, Yazgulyam, etc. However, this is an areal rather than genetic grouping.[9]

Official status

Ishkashimi is a threatened language that does not have a status of official language in the regions of its use.[4]

Language domain

The Ishkashimi language vitality, despite the positive attitudes towards the language, is declining due to increasing use by native speakers of other languages like Dari in Afghanistan and Tajik in Tajikistan in a variety of domains, such as education, religious, private domain and others.[10] For example, due to Dari being the language of the education system, almost all Ishkashimi speakers, and especially the younger ones, have high Dari proficiency.[10] Education can get complicated with the use of two languages, therefore schools prefer to use Dari. Instructions are solely in Dari, but rarely will teachers speak Ishkashimi to students for explanations. Similar to schools, religion is widely practiced with Dari especially for preaching and prayers, and when it comes to mass media and the government, Dari is exclusively used.[10] Meanwhile, in the private and community domains both Dari and Ishkashimi languages are used equally.[10] In Tajikistan areas Ishkashimi is a first choice for communication between family members and in private conversations between friends and coworkers, however the use of Tajik and Wakhi languages in other domains leads to decline in Ishkashimi use.[5] There is an understanding in the Ishkashimi speaking community that the language can face a possible extinction because of its limited use .[10]

Dialects/Varieties

There is an Afghan and Tajik Ishkashimi varieties of Ishkashimi language, and they are considered to be mutually comprehensible, as some sociolinguistic questionnaires demonstrated.[10]

Phonology

Vowels

There are seven vowel phonemes: a, e, i, o, u, u, and ə [3]

| 3 Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long and stable | e | i, | o | u | u ⟨о, u⟩ |

| Varying | a ⟨a, å⟩ | ||||

| Short | ə | ||||

Consonants

There are thirty one consonant phonemes:[3]

| Labial | Dental/ | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | t | t | y | k | q |

| p | d | d | g | x | |

| b | c [ts] | ṧ | y | ||

| w | j [dz] | žá | |||

| f | č | čˊ | |||

| f | ǰ | l | |||

| s | |||||

| z | |||||

| š | |||||

| ž | |||||

| n | |||||

| l | |||||

| r |

Special features

Ishkashimi, as one of the Pamir languages, does not contain velar fricative phonemes, which is possibly the result of being influenced by Persian and Indo-Aryan languages throughout the history of its development. Also the use of the consonant [h] in the language is optional.[3]

Stress

There are many exceptions, but as a rule stress falls on the last syllable in a word with multiple syllables. Sometimes, as a result of the rhythm in the phrase, the stress will freely move to syllables other than the last syllable.[3]

Grammar

Morphology

- Grammatical gender is not used.

- There is no variation between adjectives and no distinction in number.

- The expression of comparatives and superlatives is done through syntax and adverbial modifiers, while pre- and postpositions and suffixes are used for case relations.[3]

Suffixes

| Function | Suffixes | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Plural | -ó | olax-ó (mountains) |

| Indefinite article | -(y)i | |

| Derivation | -don, -dor, -bon |

Pronouns

| Personal pronouns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||

| I | we | you | they | |

| az (i) | məx(o) | təməx | tə | |

| Demonstrative pronouns (used for third person pronouns*) | ||

|---|---|---|

| this (near me) | that (near you) | that (near him/them)(near him/them) |

Numerals

| Orthography | Value | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| uk (ug) | 1 | |

| də(w) | 2 | |

| ru(y) | 3 | |

| cəfur | 4 | |

| punz | 5 | |

| xul/lá | 6 | |

| uvd | 7 | |

| uvd | 8 | |

| uvd | 9 | |

| da | 10 | Loan from Persian |

Tenses

| STEM | FORMATION | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| Present Stem | personal endings | |

| Past Stem | endings are movable | γažd-əm (“I said”) |

| Perfect Stem | endings are movable | γaž-əm ("I say") |

Vocabulary

Borrowed words

A significant part of Ishkashimi vocabulary contains words and syntactic structures that were borrowed from other languages, the reason behind it is a regular and close contact of Ishkashimi speakers with other languages.[11] For example, the history of the focus particle "Faqat" (Eng: only) shows that it was borrowed from Persian language, which was earlier borrowed by Persian from Arabic.[11]

Taboo words

Taboo words were formed and added into Ishkashimi language as a result of use of ancient epithets and of derivation of the words from other languages, often followed by the change of their meaning and pronunciation. Some of the taboo Ishkashimi words, which are also similarly seen as taboo in other Pamir languages, are:[12]

- Xirs - for bear

- Sabilik - for wolf

- Urvesok - for fox

- Si - for hare

- Purk - for mouse/rat

Writing system

Ishkashimi is a non-written language that does not have a writing system or literature, and in the previous centuries the Persian language, which dominated the region, was used to write down some of the traditional folklore.[10] There were, however, some efforts made at the end of the twentieth century to implement a writing system based on Cyrillic alphabet.[10]

Written sources

The first attempts by linguists to collect and organize data about the Ishkashimi language were made around the beginning of the 19th century, and were later continued by Russian and Ishkashimi linguists, like T. Pakhalina.[13] Before any systematic description and documentation of Ishkashimi language, the researchers collected some random vocabulary examples and mentioned the language in the works about Iranian languages.[10] Only in the end of the twentieth century linguists created a more comprehensive description of Ishkashimi language.[10]

References

- Ishkashimi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Nuclear Ishkashimi". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Steblin-Kamensky, I.M. (1998). "EŠKĀŠ(E)MĪ". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- "Ishkashimi". Ethnologue.

- Dodykhudoeva, Leila. "Data Elicitation in Endangered Pamiri communities: Interdependence of Language and History". academia.edu.

- "Ishkashimi". Glottolog.

- Grierson, George Abraham (1921). "Specimens of Languages of the Eranian Family: Compiled and Edited by George Abraham Grierson". Superintendent Government Printing. 10: 505–508 – via Archive.org.

- Ahn, E. S.; Smagulova, J. (15 Jan 2016). Language Change in Central Asia. Walter de Gruyter.

- Windfuhr, Gernot (2013-05-13). The Iranian Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781135797034.

- Beck, Simone. The Effect of Accessibility on Language Vitality: The Ishkashimi and the Sanglechi Speech Varieties in Afghanistan. (2007)

- Karvovskaya, Elena (2015). "'Also' in Ishkashimi: additive particle and sentence connector". Interdisciplinary Studies on Information Structure. 17: 77.

- Bauer, Brigitte L. M.; Pinault, Georges-Jean (2003-01-01). Language in Time and Space: A Festschrift for Werner Winter on the Occasion of his 80th Birthday. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110897722.

- Tiessen, C., Abbess, E., Müller, K., Paul, D., Tiessen, G. (2010). "Ishkashimi: a father's language" (Survey report). Sil.org. Tajikistan. p. 3. Retrieved 10 February 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

Bibliography

- Bauer, B. L., & Pinault, G. J. (Eds.). (2003). Language in time and space: a festschrift for Werner Winter on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Mouton De Gruyter.

- Beck, S. (2012). The effect of accessibility on language vitality: the Ishkashimi and the Sanglechi speech varieties in Afghanistan. Linguistic Discovery, 10(2), pp. 196–234.

- Dodykhudoeva L., R., & Ivanov V., B. Data Elicitation in Endangered Pamiri communities: Interdependence of Language and History. p. 3.

- Grierson, G. A. (1921). Specimens of Languages of the Eranian Family: Compiled and Edited by George Abraham Grierson. Superintendent Government Printing, India. pp. 505–508.

- Ishkashimi. Glottolog.

- Ishkashimi. Ethnologue.

- Karvovskaya, L. (2013). ‘Also’ in Ishkashimi: additive particle and sentence connector. Interdisciplinary Studies on Information Structure Vol. 17, p. 75.

- Steblin-Kamensky, I. M. (1998). "EŠKĀŠ(E)MĪ (Ishkashmi)." In Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition.

- Tiessen, C., Abbess, E., Müller, K., Paul, D., Tiessen, G., (2010). "Ishkashimi: a father's language" (Survey report). Sil.org. Tajikistan. p. 3.

- Windfuhr, G. (2013). "The Iranian Languages". Routledge. ISBN 9781135797034, pp. 773–777.

External links

- Encyclopaedia Iranica - Eskasemi (Ishkashimi)

- The Languages of Tajikistan in Perspective by Iraj Bashiri

- The Formation and Consolidation of Pamiri Ethnic Identity in Tajikistan (Doctoral Dissertation) by Suhrobsho Davlatshoev

- Ishkashimi story with English translation recorded by George Abraham Grierson (1920)

- Ishkashimi-English Vocabulary List

- English-Ishkashimi- Zebaki-Wakhi-Yazghulami Vocabulary

- Grierson G. A. Ishkashmi, Zebaki, and Yazghulami, an account of three Eranian dialects. (1920)

- Grierson G. A. Specimens of Languages of the Eranian Family. Vol X. Linguistic Survey of India. (1968)