Ipomoea

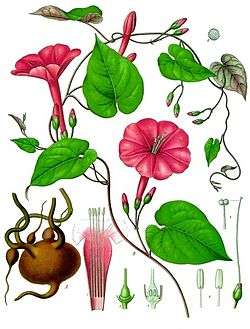

Ipomoea (/ˌɪpəˈmiːə, -poʊ-/[3][4]) is the largest genus in the flowering plant family Convolvulaceae, with over 600 species. It is a large and diverse group with common names including morning glory, water convolvulus or kangkung, sweet potato, bindweed, moonflower, etc.[5]

- "Ipomoea" is also a novel by John Rackham, published by Ace Books in 1969.

| Ipomoea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ipomoea carnea in Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Convolvulaceae |

| Tribe: | Ipomoeeae |

| Genus: | Ipomoea L. 1753[1] |

| Species | |

|

More than 600, see list | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

The most widespread common name is morning glories, but there are also species in related genera bearing the same common name. Those formerly separated in Calonyction[6] (Greek καλός kalós "good" and νύξ, νυκτός núx, nuktós, "night") are called moonflowers.[5] The generic name is derived from the Greek ἴψ, ἰπός (íps, ipós), meaning "woodworm", and ὅμοιος (hómoios), meaning "resembling." It refers to their twining habit.[7] The genus occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, and comprises annual and perennial herbaceous plants, lianas, shrubs and small trees; most of the species are twining climbing plants.

Uses and ecology

Human use of Ipomoea include:

- Most species have spectacular, colorful flowers and are often grown as ornamentals, and a number of cultivars have been developed. Their deep flowers attract large Lepidoptera - especially Sphingidae such as the pink-spotted hawk moth (Agrius cingulata) - or even hummingbirds.

- The genus includes food crops; the tubers of sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) and the leaves of water spinach (I. aquatica) are commercially important food items and have been for millennia. The sweet potato is one of the Polynesian "canoe plants", transplanted by settlers on islands throughout the Pacific. Water spinach is used all over eastern Asia and the warmer regions of the Americas as a key component of well-known dishes, such as canh chua rau muống (Mekong sour soup) or callaloo; its numerous local names attest to its popularity. Other species are used on a smaller scale, e.g. the whitestar potato (I. lacunosa) traditionally eaten by some Native Americans, such as the Chiricahua Apaches, or the Australian bush potato (I. costata).

- Peonidin, an anthocyanidin potentially useful as a food additive, is present in significant quantities in the flowers of the 'Heavenly Blue' cultivars.

- Moon vine (I. alba) sap was used for vulcanization of the latex of Castilla elastica (Panama rubber tree, Nahuatl: olicuáhuitl) to rubber; as it happens, the rubber tree seems well-suited for the vine to twine upon, and the two species are often found together. As early as 1600 BCE, the Olmecs produced the balls used in the Mesoamerican ballgame.[8]

- The root called John the Conqueror in hoodoo and used in lucky and/or sexual charms (though apparently not as a component of love potions, because it is a strong laxative if ingested) usually seems to be from I. jalapa. The testicle-like dried tubers are carried as amulets and rubbed by the users to gain good luck in gambling or flirting. As Willie Dixon wrote, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, in his song "Rub My Root" (a Muddy Waters version is titled "My John the Conquer Root"):

- My pistol may snap, my mojo is frail

- But I rub my root, my luck will never fail

- When I rub my root, my John the Conquer root

- Aww, you know there ain't nothin' she can do, Lord,

- I rub my John the Conquer root

As medicine and entheogen

Humans use Ipomoea for their content of medical and psychoactive compounds, mainly alkaloids. Some species are renowned for their properties in folk medicine and herbalism; for example Vera Cruz jalap (I. jalapa) and Tampico jalap (I. simulans) are used to produce jalap, a cathartic preparation accelerating the passage of stool. Kiribadu Ala (giant potato, I. mauritiana) is one of the many ingredients of chyawanprash, the ancient Ayurvedic tonic called "the elixir of life" for its wide-ranging properties.

The leaves of I. batatas are eaten as a vegetable, and have been shown to slow oxygenation of LDLs, with some similar potential health benefits to green tea and grape polyphenols.[9]

Other species were and still are used as potent entheogens. Seeds of Mexican morning glory (tlitliltzin, I. tricolor) were thus used by Aztecs and Zapotecs in shamanistic and priestly divination rituals, and at least by the former also as a poison, to give the victim a "horror trip" (see also Aztec entheogenic complex). Beach moonflower (I. violacea) was also used thus, and the cultivars called 'Heavenly Blue Morning Glory', touted today for their psychoactive properties, seem to represent an indeterminable assembly of hybrids of these two species.

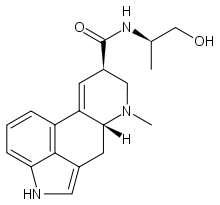

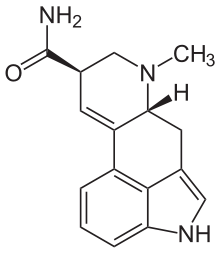

Ergoline derivatives (lysergamides) are probably responsible for the entheogenic activity. Ergine (LSA), isoergine, D-lysergic acid N-(α-hydroxyethyl)amide and lysergol have been isolated from I. tricolor, I. violacea and/or purple morning glory (I. purpurea); although these are often assumed to be the cause of the plants' effects, this is not supported by scientific studies, which show although they are psychoactive, they are not notably hallucinogenic. Alexander Shulgin in TiHKAL suggests ergonovine is responsible, instead. It has verified psychoactive properties, though as yet other undiscovered lysergamides possibly are present in the seeds.

Though most often noted as "recreational" drugs, the lysergamides are also of medical importance. Ergonovine enhances the action of oxytocin, used to still post partum bleeding. Ergine induces drowsiness and a relaxed state and might be useful in treating anxiety disorder. Whether Ipomoea species are a useful source of these compounds remains to be determined. In any case, in some jurisdictions certain Ipomoea are regulated, e.g. by the Louisiana State Act 159 which bans cultivation of I. violacea except for ornamental purposes.

Pests and diseases

Many herbivores avoid morning glories such as Ipomoea, as the high alkaloid content makes these plants unpalatable, if not toxic. Nonetheless, Ipomoea species are used as food plants by the caterpillars of certain Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths); see list of Lepidoptera which feed on Ipomoea. For a selection of diseases of the sweet potato (I. batatas), many of which also infect other members of this genus, see List of sweet potato diseases. List of Ipomoea species

Gallery

Whitestar potato (I. lacunosa)

Whitestar potato (I. lacunosa) Ipomoea barbatisepala

Ipomoea barbatisepala.jpg)

Ipomoea macrantha

Ipomoea macrantha Ipomoea marginata

Ipomoea marginata

Ipomoea pes-caprae in China

Ipomoea pes-caprae in China_-_Sanibel_Island%2C_FL%2C_USA_03.jpg) Ipomoea sagittata in Florida

Ipomoea sagittata in Florida Morning glory. Eastern Siberia

Morning glory. Eastern Siberia

References

- "Genus: Ipomoea L." Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2007-10-05. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- "Ipomoea L." Plants of the World Online. Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Ipomoea". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- Gunn, Charles R. (1972). "moonflower". Brittonia. 24 (2): 150–168. doi:10.2307/2805866. JSTOR 2805866.

- Gunn, Charles R. (1972). "Calonyction". Brittonia. 24 (2): 150–168. doi:10.2307/2805866. JSTOR 2805866.

- Austin, Daniel F. (2004). Florida Ethnobotany. CRC Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-8493-2332-4.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology Summer Institute in Materials Science and Material Culture: Rubber Processing in Ancient Mesoamerica. Retrieved 2007-NOV-22.

- Nagai, Miu; Tani, Mariko; Kishimoto, Yoshimi; Iizuka, Maki; Saita, Emi; Toyozaki, Miku; Kamiya, Tomoyasu; Ikeguchi, Motoya; Kondo, Kazuo (2011). "Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaves suppressed oxidation of low density lipoprotein (LDL) in vitro and in human subjects". J Clin Biochem Nutr. 48 (3): 203–8. doi:10.3164/jcbn.10-84. PMC 3082074. PMID 21562639.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ipomoea. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Ipomoea |

- Dressler, S.; Schmidt, M. & Zizka, G. (2014). "Ipomoea". African plants – a Photo Guide. Frankfurt/Main: Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg.