Introduction to gauge theory

A gauge theory is a type of theory in physics. The word gauge means a measurement, a thickness, an in-between distance (as in railroad tracks), or a resulting number of units per certain parameter (a number of loops in an inch of fabric or a number of lead balls in a pound of ammunition).[1] Modern theories describe physical forces in terms of fields, e.g., the electromagnetic field, the gravitational field, and fields that describe forces between the elementary particles. A general feature of these field theories is that the fundamental fields cannot be directly measured; however, some associated quantities can be measured, such as charges, energies, and velocities. For example, say you cannot measure the diameter of a lead ball, but you can determine how many lead balls, which are equal in every way, are required to make a pound. Using the number of balls, the elemental mass of lead, and the formula for calculating the volume of a sphere from its diameter, one could indirectly determine the diameter of a single lead ball. In field theories, different configurations of the unobservable fields can result in identical observable quantities. A transformation from one such field configuration to another is called a gauge transformation;[2][3] the lack of change in the measurable quantities, despite the field being transformed, is a property called gauge invariance. For example, if you could measure the color of lead balls and discover that when you change the color, you still fit the same number of balls in a pound, the property of "color" would show gauge invariance. Since any kind of invariance under a field transformation is considered a symmetry, gauge invariance is sometimes called gauge symmetry. Generally, any theory that has the property of gauge invariance is considered a gauge theory.

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

|

Background

|

|

|

Scientists

|

For example, in electromagnetism the electric and magnetic fields, E and B are observable, while the potentials V ("voltage") and A (the vector potential) are not.[4] Under a gauge transformation in which a constant is added to V, no observable change occurs in E or B.

With the advent of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, and with successive advances in quantum field theory, the importance of gauge transformations has steadily grown. Gauge theories constrain the laws of physics, because all the changes induced by a gauge transformation have to cancel each other out when written in terms of observable quantities. Over the course of the 20th century, physicists gradually realized that all forces (fundamental interactions) arise from the constraints imposed by local gauge symmetries, in which case the transformations vary from point to point in space and time. Perturbative quantum field theory (usually employed for scattering theory) describes forces in terms of force-mediating particles called gauge bosons. The nature of these particles is determined by the nature of the gauge transformations. The culmination of these efforts is the Standard Model, a quantum field theory that accurately predicts all of the fundamental interactions except gravity.

History and importance

The earliest field theory having a gauge symmetry was Maxwell's formulation, in 1864–65, of electrodynamics ("A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field"). The importance of this symmetry remained unnoticed in the earliest formulations. Similarly unnoticed, Hilbert had derived Einstein's equations of general relativity by postulating a symmetry under any change of coordinates. Later Hermann Weyl, inspired by success in Einstein's general relativity, conjectured (incorrectly, as it turned out) in 1919 that invariance under the change of scale or "gauge" (a term inspired by the various track gauges of railroads) might also be a local symmetry of electromagnetism.[5][6]:5, 12 Although Weyl's choice of the gauge was incorrect, the name "gauge" stuck to the approach. After the development of quantum mechanics, Weyl, Fock and London modified their gauge choice by replacing the scale factor with a change of wave phase, and applying it successfully to electromagnetism.[7] Gauge symmetry was generalized mathematically in 1954 by Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills in an attempt to describe the strong nuclear forces. This idea, dubbed Yang–Mills theory, later found application in the quantum field theory of the weak force, and its unification with electromagnetism in the electroweak theory.

The importance of gauge theories for physics stems from their tremendous success in providing a unified framework to describe the quantum-mechanical behavior of electromagnetism, the weak force and the strong force. This gauge theory, known as the Standard Model, accurately describes experimental predictions regarding three of the four fundamental forces of nature.

In classical physics

Electromagnetism

Historically, the first example of gauge symmetry to be discovered was classical electromagnetism. A static electric field can be described in terms of an electric potential (voltage) that is defined at every point in space, and in practical work it is conventional to take the Earth as a physical reference that defines the zero level of the potential, or ground. But only differences in potential are physically measurable, which is the reason that a voltmeter must have two probes, and can only report the voltage difference between them. Thus one could choose to define all voltage differences relative to some other standard, rather than the Earth, resulting in the addition of a constant offset.[8] If the potential is a solution to Maxwell's equations then, after this gauge transformation, the new potential is also a solution to Maxwell's equations and no experiment can distinguish between these two solutions. In other words, the laws of physics governing electricity and magnetism (that is, Maxwell equations) are invariant under gauge transformation.[9] Maxwell's equations have a gauge symmetry.

Generalizing from static electricity to electromagnetism, we have a second potential, the magnetic vector potential A, which can also undergo gauge transformations. These transformations may be local. That is, rather than adding a constant onto V, one can add a function that takes on different values at different points in space and time. If A is also changed in certain corresponding ways, then the same E and B fields result. The detailed mathematical relationship between the fields E and B and the potentials V and A is given in the article Gauge fixing, along with the precise statement of the nature of the gauge transformation. The relevant point here is that the fields remain the same under the gauge transformation, and therefore Maxwell's equations are still satisfied.

Gauge symmetry is closely related to charge conservation. Suppose that there existed some process by which one could briefly violate conservation of charge by creating a charge q at a certain point in space, 1, moving it to some other point 2, and then destroying it. We might imagine that this process was consistent with conservation of energy. We could posit a rule stating that creating the charge required an input of energy E1=qV1 and destroying it released E2=qV2, which would seem natural since qV measures the extra energy stored in the electric field because of the existence of a charge at a certain point. Outside of the interval during which the particle exists, conservation of energy would be satisfied, because the net energy released by creation and destruction of the particle, qV2-qV1, would be equal to the work done in moving the particle from 1 to 2, qV2-qV1. But although this scenario salvages conservation of energy, it violates gauge symmetry. Gauge symmetry requires that the laws of physics be invariant under the transformation , which implies that no experiment should be able to measure the absolute potential, without reference to some external standard such as an electrical ground. But the proposed rules E1=qV1 and E2=qV2 for the energies of creation and destruction would allow an experimenter to determine the absolute potential, simply by comparing the energy input required to create the charge q at a particular point in space in the case where the potential is and respectively. The conclusion is that if gauge symmetry holds, and energy is conserved, then charge must be conserved.[10]

General relativity

As discussed above, the gauge transformations for classical (i.e., non-quantum mechanical) general relativity are arbitrary coordinate transformations.[11] Technically, the transformations must be invertible, and both the transformation and its inverse must be smooth, in the sense of being differentiable an arbitrary number of times.

An example of a symmetry in a physical theory: translation invariance

Some global symmetries under changes of coordinate predate both general relativity and the concept of a gauge. For example, Galileo and Newton introduced the notion of translation invariance, an advancement from the Aristotelian concept that different places in space, such as the earth versus the heavens, obeyed different physical rules.

Suppose, for example, that one observer examines the properties of a hydrogen atom on Earth, the other—on the Moon (or any other place in the universe), the observer will find that their hydrogen atoms exhibit completely identical properties. Again, if one observer had examined a hydrogen atom today and the other—100 years ago (or any other time in the past or in the future), the two experiments would again produce completely identical results. The invariance of the properties of a hydrogen atom with respect to the time and place where these properties were investigated is called translation invariance.

Recalling our two observers from different ages: the time in their experiments is shifted by 100 years. If the time when the older observer did the experiment was t, the time of the modern experiment is t+100 years. Both observers discover the same laws of physics. Because light from hydrogen atoms in distant galaxies may reach the earth after having traveled across space for billions of years, in effect one can do such observations covering periods of time almost all the way back to the Big Bang, and they show that the laws of physics have always been the same.

In other words, if in the theory we change the time t to t+100 years (or indeed any other time shift) the theoretical predictions do not change.[12]

Another example of a symmetry: the invariance of Einstein's field equation under arbitrary coordinate transformations

In Einstein's general relativity, coordinates like x, y, z, and t are not only "relative" in the global sense of translations like , rotations, etc., but become completely arbitrary, so that, for example, one can define an entirely new time-like coordinate according to some arbitrary rule such as , where has units of time, and yet Einstein's equations will have the same form.[11][13]

Invariance of the form of an equation under an arbitrary coordinate transformation is customarily referred to as general covariance, and equations with this property are referred to as written in the covariant form. General covariance is a special case of gauge invariance.

Maxwell's equations can also be expressed in a generally covariant form, which is as invariant under general coordinate transformation as Einstein's field equation.

In quantum mechanics

Quantum electrodynamics

Until the advent of quantum mechanics, the only well known example of gauge symmetry was in electromagnetism, and the general significance of the concept was not fully understood. For example, it was not clear whether it was the fields E and B or the potentials V and A that were the fundamental quantities; if the former, then the gauge transformations could be considered as nothing more than a mathematical trick.

Aharonov–Bohm experiment

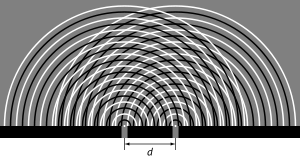

In quantum mechanics, a particle such as an electron is also described as a wave. For example, if the double-slit experiment is performed with electrons, then a wave-like interference pattern is observed. The electron has the highest probability of being detected at locations where the parts of the wave passing through the two slits are in phase with one another, resulting in constructive interference. The frequency of the electron wave is related to the kinetic energy of an individual electron particle via the quantum-mechanical relation E = hf. If there are no electric or magnetic fields present in this experiment, then the electron's energy is constant, and, for example, there will be a high probability of detecting the electron along the central axis of the experiment, where by symmetry the two parts of the wave are in phase.

But now suppose that the electrons in the experiment are subject to electric or magnetic fields. For example, if an electric field were imposed on one side of the axis but not on the other, the results of the experiment would be affected. The part of the electron wave passing through that side oscillates at a different rate, since its energy has had −eV added to it, where −e is the charge of the electron and V the electrical potential. The results of the experiment will be different, because phase relationships between the two parts of the electron wave have changed, and therefore the locations of constructive and destructive interference will be shifted to one side or the other. It is the electric potential that occurs here, not the electric field, and this is a manifestation of the fact that it is the potentials and not the fields that are of fundamental significance in quantum mechanics.

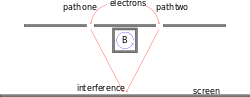

Explanation with potentials

It is even possible to have cases in which an experiment's results differ when the potentials are changed, even if no charged particle is ever exposed to a different field. One such example is the Aharonov–Bohm effect, shown in the figure.[14] In this example, turning on the solenoid only causes a magnetic field B to exist within the solenoid. But the solenoid has been positioned so that the electron cannot possibly pass through its interior. If one believed that the fields were the fundamental quantities, then one would expect that the results of the experiment would be unchanged. In reality, the results are different, because turning on the solenoid changed the vector potential A in the region that the electrons do pass through. Now that it has been established that it is the potentials V and A that are fundamental, and not the fields E and B, we can see that the gauge transformations, which change V and A, have real physical significance, rather than being merely mathematical artifacts.

Gauge invariance: the results of the experiments are independent of the choice of the gauge for the potentials

Note that in these experiments, the only quantity that affects the result is the difference in phase between the two parts of the electron wave. Suppose we imagine the two parts of the electron wave as tiny clocks, each with a single hand that sweeps around in a circle, keeping track of its own phase. Although this cartoon ignores some technical details, it retains the physical phenomena that are important here.[15] If both clocks are sped up by the same amount, the phase relationship between them is unchanged, and the results of experiments are the same. Not only that, but it is not even necessary to change the speed of each clock by a fixed amount. We could change the angle of the hand on each clock by a varying amount θ, where θ could depend on both the position in space and on time. This would have no effect on the result of the experiment, since the final observation of the location of the electron occurs at a single place and time, so that the phase shift in each electron's "clock" would be the same, and the two effects would cancel out. This is another example of a gauge transformation: it is local, and it does not change the results of experiments.

Summary

In summary, gauge symmetry attains its full importance in the context of quantum mechanics. In the application of quantum mechanics to electromagnetism, i.e., quantum electrodynamics, gauge symmetry applies to both electromagnetic waves and electron waves. These two gauge symmetries are in fact intimately related. If a gauge transformation θ is applied to the electron waves, for example, then one must also apply a corresponding transformation to the potentials that describe the electromagnetic waves.[16] Gauge symmetry is required in order to make quantum electrodynamics a renormalizable theory, i.e., one in which the calculated predictions of all physically measurable quantities are finite.

Types of gauge symmetries

The description of the electrons in the subsection above as little clocks is in effect a statement of the mathematical rules according to which the phases of electrons are to be added and subtracted: they are to be treated as ordinary numbers, except that in the case where the result of the calculation falls outside the range of 0≤θ<360°, we force it to "wrap around" into the allowed range, which covers a circle. Another way of putting this is that a phase angle of, say, 5° is considered to be completely equivalent to an angle of 365°. Experiments have verified this testable statement about the interference patterns formed by electron waves. Except for the "wrap-around" property, the algebraic properties of this mathematical structure are exactly the same as those of the ordinary real numbers.

In mathematical terminology, electron phases form an Abelian group under addition, called the circle group or U(1). "Abelian" means that addition commutes, so that θ + φ = φ + θ. Group means that addition associates and has an identity element, namely "0". Also, for every phase there exists an inverse such that the sum of a phase and its inverse is 0. Other examples of abelian groups are the integers under addition, 0, and negation, and the nonzero fractions under product, 1, and reciprocal.

As a way of visualizing the choice of a gauge, consider whether it is possible to tell if a cylinder has been twisted. If the cylinder has no bumps, marks, or scratches on it, we cannot tell. We could, however, draw an arbitrary curve along the cylinder, defined by some function θ(x), where x measures distance along the axis of the cylinder. Once this arbitrary choice (the choice of gauge) has been made, it becomes possible to detect it if someone later twists the cylinder.

In 1954, Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills proposed to generalize these ideas to noncommutative groups. A noncommutative gauge group can describe a field that, unlike the electromagnetic field, interacts with itself. For example, general relativity states that gravitational fields have energy, and special relativity concludes that energy is equivalent to mass. Hence a gravitational field induces a further gravitational field. The nuclear forces also have this self-interacting property.

Gauge bosons

Surprisingly, gauge symmetry can give a deeper explanation for the existence of interactions, such as the electric and nuclear interactions. This arises from a type of gauge symmetry relating to the fact that all particles of a given type are experimentally indistinguishable from one another. Imagine that Alice and Betty are identical twins, labeled at birth by bracelets reading A and B. Because the girls are identical, nobody would be able to tell if they had been switched at birth; the labels A and B are arbitrary, and can be interchanged. Such a permanent interchanging of their identities is like a global gauge symmetry. There is also a corresponding local gauge symmetry, which describes the fact that from one moment to the next, Alice and Betty could swap roles while nobody was looking, and nobody would be able to tell. If we observe that Mom's favorite vase is broken, we can only infer that the blame belongs to one twin or the other, but we cannot tell whether the blame is 100% Alice's and 0% Betty's, or vice versa. If Alice and Betty are in fact quantum-mechanical particles rather than people, then they also have wave properties, including the property of superposition, which allows waves to be added, subtracted, and mixed arbitrarily. It follows that we are not even restricted to complete swaps of identity. For example, if we observe that a certain amount of energy exists in a certain location in space, there is no experiment that can tell us whether that energy is 100% A's and 0% B's, 0% A's and 100% B's, or 20% A's and 80% B's, or some other mixture. The fact that the symmetry is local means that we cannot even count on these proportions to remain fixed as the particles propagate through space. The details of how this is represented mathematically depend on technical issues relating to the spins of the particles, but for our present purposes we consider a spinless particle, for which it turns out that the mixing can be specified by some arbitrary choice of gauge θ(x), where an angle θ = 0° represents 100% A and 0% B, θ = 90° means 0% A and 100% B, and intermediate angles represent mixtures.

According to the principles of quantum mechanics, particles do not actually have trajectories through space. Motion can only be described in terms of waves, and the momentum p of an individual particle is related to its wavelength λ by p = h/λ. In terms of empirical measurements, the wavelength can only be determined by observing a change in the wave between one point in space and another nearby point (mathematically, by differentiation). A wave with a shorter wavelength oscillates more rapidly, and therefore changes more rapidly between nearby points. Now suppose that we arbitrarily fix a gauge at one point in space, by saying that the energy at that location is 20% A's and 80% B's. We then measure the two waves at some other, nearby point, in order to determine their wavelengths. But there are two entirely different reasons that the waves could have changed. They could have changed because they were oscillating with a certain wavelength, or they could have changed because the gauge function changed from a 20–80 mixture to, say, 21–79. If we ignore the second possibility, the resulting theory doesn't work; strange discrepancies in momentum will show up, violating the principle of conservation of momentum. Something in the theory must be changed.

Again there are technical issues relating to spin, but in several important cases, including electrically charged particles and particles interacting via nuclear forces, the solution to the problem is to impute physical reality to the gauge function θ(x). We say that if the function θ oscillates, it represents a new type of quantum-mechanical wave, and this new wave has its own momentum p = h/λ, which turns out to patch up the discrepancies that otherwise would have broken conservation of momentum. In the context of electromagnetism, the particles A and B would be charged particles such as electrons, and the quantum mechanical wave represented by θ would be the electromagnetic field. (Here we ignore the technical issues raised by the fact that electrons actually have spin 1/2, not spin zero. This oversimplification is the reason that the gauge field θ comes out to be a scalar, whereas the electromagnetic field is actually represented by a vector consisting of V and A.) The result is that we have an explanation for the presence of electromagnetic interactions: if we try to construct a gauge-symmetric theory of identical, non-interacting particles, the result is not self-consistent, and can only be repaired by adding electric and magnetic fields that cause the particles to interact.

Although the function θ(x) describes a wave, the laws of quantum mechanics require that it also have particle properties. In the case of electromagnetism, the particle corresponding to electromagnetic waves is the photon. In general, such particles are called gauge bosons, where the term "boson" refers to a particle with integer spin. In the simplest versions of the theory, gauge bosons are massless, but it is also possible to construct versions in which they have mass, as is the case for the gauge bosons that transmit the nuclear decay forces.

References

- "Definition of Gauge".

- Donald H. Perkins (1982) Introduction to High-Energy Physics. Addison-Wesley: 22.

- Roger Penrose (2004) The Road to Reality, p. 451. For an alternative formulation in terms of symmetries of the Lagrangian density, see p. 489. Also see J. D. Jackson (1975) Classical Electrodynamics, 2nd ed. Wiley and Sons: 176.

- For an argument that V and A are more fundamental, see Feynman, Leighton, and Sands, The Feynman Lectures, Addison Wesley Longman, 1970, II-15-7,8,12, but this is partly a matter of personal preference.

- Hermann Weyl (1919), "Eine neue Erweiterung der Relativitíatstheorie," Ann. der Physik 59, 101–133.

- K. Moriyasu (1983). An Elementary Primer for Gauge Theory. World Scientific. ISBN 978-9971-950-83-5.

- For a review and references, see Lochlainn O'Raifeartaigh and Norbert Straumann, "Gauge theory: Historical origins and some modern developments," Reviews of Modern Physics, 72 (2000), pp. 1–22, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.72.1.

- Edward Purcell (1963) Electricity and Magnetism. McGraw-Hill: 38.

- J.D. Jackson (1975) Classical Electrodynamics, 2nd ed. Wiley and Sons: 176.

- Donald H. Perkins (1982) Introduction to High-Energy Physics. Addison-Wesley: 92.

- Robert M. Wald (1984) General Relativity. University of Chicago Press: 260.

- Charles Misner, Kip Thorne, and John A. Wheeler (1973) Gravitation. W. H. Freeman: 68.

- Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler (1973) Gravitation. W. H. Freeman: 967.

- Feynman, Leighton, and Sands (1970) The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Addison Wesley, vol. II, chpt. 15, section 5.

- Richard Feynman (1985) QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. Princeton University Press.

- Donald H. Perkins (1982) Introduction to High-Energy Physics. Addison-Wesley: 332.

Further reading

These books are intended for general readers and employ the barest minimum of mathematics.

- 't Hooft, Gerard: "Gauge Theories of the Force between Elementary Particles," Scientific American, 242(6):104–138 (June 1980).

- "Press Release: The 1999 Nobel Prize in Physics". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2013. 20 Aug 2013.

- Schumm, Bruce (2004) Deep Down Things. Johns Hopkins University Press. A serious attempt by a physicist to explain gauge theory and the Standard Model.

- Feynman, Richard (2006) QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. Princeton University Press. A nontechnical description of quantum field theory (not specifically about gauge theory).