Imperial election

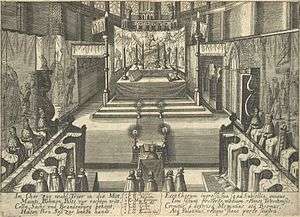

The election of a Holy Roman Emperor was generally a two-stage process whereby, from at least the 13th century, the King of the Romans was elected by a small body of the greatest princes of the Empire, the prince-electors. This was then followed shortly thereafter by his coronation as Emperor, an appointment that was normally for life.[1] In 1356, the Emperor Charles IV promulgated the Golden Bull, which became the fundamental law by which all future kings and emperors were elected.[2] After 1508, the Pope recognized election alone to be sufficient for the use of the Imperial title. The last papal coronation took place in 1530.

Although the Holy Roman Empire is perhaps the best-known example of an elective monarchy, from 1438 to 1740, a Habsburg was always elected emperor, the throne becoming de facto hereditary.[3] During that period, the emperor was elected from within the House of Habsburg.

Background

The Königswahl was the election of royal candidates in the Holy Roman Empire and its predecessors as king by a specified elective body (the Gremium). Whilst the succession to the throne of the monarch in most cultures is governed by the rules of hereditary succession, there are also elective monarchies.

There were elective monarchies in several Germanic successor states after the collapse of the Roman Empire during the Migration Period, the Early Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Poland from 1573 to 1795 (see History of Poland, period of the Aristocratic Republic).

Prince-electors

From the 13th century, the right to elect kings in the Holy Roman Empire was granted to a limited number of imperial princes, the so called prince-electors. There are various theories over the emergence of their exclusive election right.[4]

The secular electoral seats were hereditary. However, spiritual electors (and other prince-(arch)bishops) were usually elected by the cathedral chapters as religious leaders, but simultaneously ruled as monarch (prince) of a territory of imperial immediacy (which usually comprised a part of their diocesan territory). Thus the prince-bishoprics were elective monarchies too. The same holds true for prince-abbeys, whose prince-abbesses or prince-abbots were elected by a college of clerics and imperially appointed as princely rulers in a pertaining territory.

Initially seven electors chose the "King of the Romans" as the Emperor's designated heir was known. The elected king then went on to be crowned by the Pope. The prince-electors were:

Spiritual electors

Secular electors

Subsequent changes

Later additions to the electoral council were:

References

- Noble, Strauss, Osheim, Neuschel, Accampo. Western Civilization: Beyond Boundaries.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The Golden Bull of Charles IV 1356". ordham.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- "The Emperor: Qualifications". The Holy Roman Empire. Heraldica.

- Armin Wolf: Kurfürsten Archived 2015-11-18 at the Wayback Machine, article dated 25 March 2013 in the historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de portal, retrieved 16 August 2013

Literature

- Heinrich Mitteis: Die deutsche Königswahl. Ihre Rechtsgrundlagen bis zur Goldenen Bulle. 2. erweiterte Auflage. Rohrer, Brünn u. a. 1944.

- Eduard Hlawitschka: Königswahl und Thronfolge in fränkisch-karolingischer Zeit, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1975, ISBN 3-534-04685-4.

- Ulrich Schmidt: Königswahl und Thronfolge im 12. Jahrhundert. Böhlau, Cologne, etc.. 1987, ISBN 3-412-04087-8, (Forschungen zur Kaiser- und Papstgeschichte des Mittelalters. Beihefte zu J. F. Böhmer, Regesta Imperii 7), (Zugleich: Tübingen, Univ., Diss., 1985).

- Gerhard Baaken, Roderich Schmidt: Königtum, Burgen und Königsfreie. Königsumritt und Huldigungen in ottonisch-salischer Zeit. 2nd edn. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen, 1981, ISBN 3-799-56606-6 (Konstanzer Arbeitskreis für mittelalterliche Geschichte e.V. (publ.): Vorträge und Forschungen 6).