Mojeños

The Mojeños, also known as Moxeños, Moxos, or Mojos, are an indigenous people of Bolivia. They lived in south central Beni Department,[2] on both banks of the Mamore River, and on the marshy plains to its west, known as the Llanos de Mojos. The Mamore is a tributary to the Madeira River in northern Bolivia.

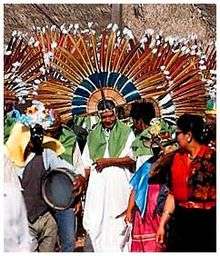

Mojeño machetero dancer at a festival in Bolivia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 42,093 (2012)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Mojeño, Spanish[2] | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Trinitario |

Mojeños were traditionally hunter-gatherers, as well as farmers and pastoralists.[2]. Jesuit missionaries established towns in the Mojos plains beginning in 1682, converting native peoples to Catholicism and establishing a system of social organization that would endure well beyond the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 [3]. Mojeño ethnic identification derives from a process of ethnogenesis as a result of this encounter between a number of pre-existing ethnic groups in this mission environment. This process occurred in several different mission towns, resulting in distinct Mojeño identities, including Mojeño-Trinitarios (Trinidad mission), Mojeño-Loretanos (Loreto mission), Mojeño-Javerianos, and Mojeño-Ignacianos (San Ignacio de Moxos mission).[4] They numbered some 30,000 in the first decade of the 20th century. Many Mojeño communities are affiliated with the Central de Pueblos Indígenas del Beni and/or the Central de Pueblos Étnicos Mojeños del Beni.[4]

Language

In addition to Spanish, many Mojeño people speak one of several indigenous languages, belonging to the Arawakan language family, including Ignaciano language. In many communities, the language is used in daily life and taught in beginning primary school grades. A dictionary of Ignaciano Mojeño has been published, and the New Testament was translated into the language in 1980.[2]

Name

They are also known as Mojos, Moxos or Moxeños.

History

Moxos Before the Jesuits

The previous inhabitants of the region, which before the independence of Bolivia was a single territory called Mojos, were the aboriginal Itonama, Cayuvava, Canichana, Tacanam and Movima.[5] Afterwards, the Moxos or the Moxeños arrived. The Moxos were from the Arawak ethnic group,[6] an ethnic group which developed a more complex culture between the Amazon rainforest and Los Llanos (South America).

For unknown reasons, between the 15th Century B.C. and the 8th Century B.C., agricultural Arawak groups from the lowlands (present-day Surinam) abandoned their lands and migrated to the west and south, bringing with them a tradition of incised ceramics. The Moxos, who were part of this population stream, built irrigation canals and crop terraces[7] as well as ritual sites.[8] Thousands of years before the Common Era, the Arawak also migrated north and populated the islands of the Caribbean Sea. This slow expansion resulted in their arrival at the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola (present-day island of the Dominican Republic and Haiti).

Pottery pieces found in the countryside of the department of Santa Cruz, Bolivia, and even in the present-day precinct of the city Santa Cruz de la Sierra, reveal that the region was populated by an Arawak tribe (known as the Chané) with a ceramic-making culture.

Writers such as Diego Felipe de Alcaya, tell of a group living between the last buttresses of the Andes Mountains and the central arm of the Guapay River. The communities all throughout this great plain region and along the banks of the river were established and allied under the superior command of a leader, whom Alcaya describes with the title of king. This king, called by the dynastic name of Grigotá, had a comfortable dwelling and wore a vividly-colored shirt. Chiefs (caciques), named as Goligoli, Tundi, and Vitupué, were subordinate to Grigotá and had control of hundreds of warriors.

As a result, the first Jesuits in Moxos encountered a developed, ancient civilization. Thousands and thousands of artificial hills up to 60 feet high dotted the landscape, along with hundreds of artificial rectangular ponds up to three feet deep, all part of a system of cultivation and irrigation. The people used the built-up high ground for farming and dug canals to unite ponds and rivers that caught water in this flood-prone region.

All these architectural and structural masterpieces can be attributed to the ancestors of the present-day Moxeños, who include the Arawak, the most extensive ethnic group in the area. The Moxos language belongs to a language family called Arawakan. The Arawak have always been famous architects, and indeed the great hydraulic works (dated to ca. 250 CE) of their ancient empire is located in the territory of Moxos.

Even today one speaks of the "Amazonian cultures" as a block, despite the differences between the various peoples. The Amazonian cosmos includes a tripartite world: the sky above, the earth here, and the underworld below. These cultures believe that the earth is controlled by a father creator, in collaboration with created spirits or dueños, masters, of places or things and with ancestors who help to maintain justice and balance. Slipping from the norm brings about a spiritual sickness that is cured by a communal search for the cause and by a variety of religious rituals, including prayers and natural remedies. In Moxos the principal dueños are the spirits of the jungle (connected with the tiger) and of the water (connected with the rainbow). Many rich dances renew the life of the community and the universe.

Jesuit mission era

Jesuit priests arriving from Santa Cruz de la Sierra began evangelizing native peoples of the region in the 1670s. They set up a series of missions near the Mamoré River for this purpose beginning with Loreto. The principal mission was established at Trinidad in 1686.[9]

The Jesuit missionaries who first encountered the Moxeños found a people with a strong belief in God as father and creator. The Jesuits accepted in their catechism the names the indigenous peoples gave to God in their own languages, trying to embrace all aspects of the culture not contrary to Christian faith or custom.[10]

See also

Notes

- "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2012 Bolivia Características de la Población". Instituto Nacional de Estadística, República de Bolivia. p. 29.

- "Ignaciano." Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Block, David (1994). Mission Culture on the Upper Amazon: Native Tradition, Jesuit Enterprise and Secular Policy in Moxos, 1660-1880; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Molina Argandoña, Wilder.; Cynthia. Vargas Melgar; Pablo. Soruco Claure (2008). Estado, identidades territoriales y autonomías en la región amazónica de Bolivia. La Paz: PIEB. p. 93. ISBN 978-99954-32-24-9.

- Historia cultural de Mojos. Trinidad, Bolivia: Parroquias de Moxos. 1988. p. 14.

- Walker, John H. (2008). "The Llanos de Mojos". In Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William H. (eds.). The Handbook of South American Archaeology. pp. 927–39. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74907-5_46. ISBN 978-0-387-74906-8.

- Lombardo, Umberto; Prümers, Heiko (2010). "Pre-Columbian human occupation patterns in the eastern plains of the Llanos de Moxos, Bolivian Amazonia". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (8): 1875–85. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.02.011.

- Denevan, William (1966). The aboriginal cultural geography of the Llanos de Mojos of Bolivia. Berkeley; Los Angeles: U of California Press. p. 46.

- Gott, Richard (1993). Land without evil : utopian journeys across the South American watershed. London; New York: Verso. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-86091-398-6.

- http://www.companysj.com/v153/returntosanignacio.html%5B%5D

External links

- Mehináku material culture, National Museum of the American Indian

- Moxos Indians at the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia.

- "The Amazon and Madeira Rivers: Sketches and Descriptions from the Note-Book of an Explorer" is a book from 1875 that has a chapter about the Moxo people.