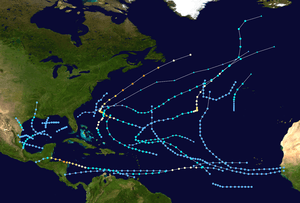

Hurricane Ella (1978)

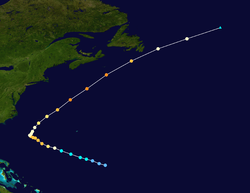

Hurricane Ella was the strongest hurricane on record in Canadian waters. It formed on August 30, 1978 to the south of Bermuda, and quickly intensified as it tracked west-northwestward. By September 1, Ella reached winds of 125 mph (205 km/h), and it was expected to pass close to the Outer Banks of North Carolina during the busy Labor Day Weekend. The hurricane became stationary for about 24 hours, and later turned to the northeast away from the coast. On September 4, Ella reached Category 4 status on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale off the coast of Nova Scotia. It subsequently weakened, passing southeast of Newfoundland before being absorbed by a large extratropical cyclone.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

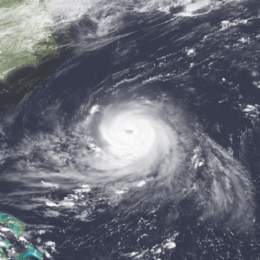

Hurricane Ella at its initial peak intensity southeast of Cape Hatteras on September 1 | |

| Formed | August 30, 1978 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 5, 1978 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 956 mbar (hPa); 28.23 inHg |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Damage | None |

| Areas affected | North Carolina, Newfoundland |

| Part of the 1978 Atlantic hurricane season | |

In North Carolina, the National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane watch due to the large influx of people expected during the holiday weekend. As such, there was a significant drop in tourism, although no significantly adverse weather occurred along the Outer Banks. High waves and some minor beach erosion was reported, but there were no deaths, injuries, or damage from Ella. By the time the hurricane passed Newfoundland, the strongest winds were to the southeast of the center, and as a result, no significant impact was reported on Canada.

Meteorological history

Towards the end of August 1978, a cold front stalled and dissipated across the western Atlantic Ocean, which spawned a tropical disturbance southeast of Bermuda on August 28. A circulation was present, and it developed into a tropical depression on August 30, about 520 miles (840 km) south-southeast of Bermuda. Located to the south of a subtropical ridge, the depression tracked steadily west-northwestward, and it attained tropical storm status 18 hours after forming, based on a nearby ship observation.[1] At 2200 UTC on August 30, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) initiated advisories on the system,[2] but three hours later, as its rapid strengthening became evident, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Ella.[3]

Tropical Storm Ella intensified quickly and reached hurricane status late on August 31, based on confirmation from nearby ship reports and a Hurricane Hunters flight.[1] At the time, the hurricane was forecast to avoid making landfall on North Carolina and ultimately turn northeastward, although it was expected to pass within 50 miles (85 km) of land during the busy Labor Day Weekend.[4] On September 1, Ella reached a preliminary peak intensity of 125 mph (205 km/h), a major hurricane and a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. At the same time a short-wave trough reached the East Coast of the United States. The trough caused the hurricane to decelerate and turn slightly to the north, and a ridge behind the trough caused Ella to become nearly stationary for 24 hours.[1] During that time, the threat toward the North Carolina coast diminished, and concurrently, the winds decreased as the convection diminished.[5]

On September 3, another trough exited the coast of the United States, allowing the hurricane to accelerate toward the northeast through the diminished ridge.[1] By that time, the winds had decreased to 80 mph (130 km/h),[1] although forecasters expected baroclinic instability to maintain much of the cyclone's remaining force.[6] Instead of continued weakening, the hurricane began to significantly re-intensify. Early on September 4, Ella again reached major hurricane status, and later that day it peaked with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h); at the time it was about 335 miles (540 km) south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and its peak winds were measured by Hurricane Hunters.[1] This made it the strongest hurricane ever recorded in Canadian waters.[7] Weakening began immediately after peak intensity due to cooler water temperatures.[1] Early on September 5, Ella passed very near Cape Race, although the strongest winds were south and east of the center.[8] Associated convection became completely removed from the center,[9] and the hurricane became extratropical as it was absorbed by a larger mid-latitude system.[1]

Preparations and impact

On September 1, as Hurricane Ella was strengthening to its first peak in strength, the National Hurricane Center anticipated a track near the North Carolina coast during the busy Labor Day Weekend; as a result, the agency issued a hurricane watch for the Outer Banks.[1] The Cape Hatteras National Weather Service office requested radio and television stations in the threatened area to continue broadcasting beyond normal hours, so to convey storm updates to people in the region.[10] Additionally, the Cape Hatteras agency issued an advisory for small craft to remain at port, and also for affected people to "keep alert [and] ignore rumors."[11] Due to the threat, campgrounds on Ocracoke Island and Cape Lookout, each only accessible by ferry, were closed to reduce their populations.[12]

The hurricane ultimately stayed far away from the coast,[1] and the heavy rainfall and thunderstorms remained at least 50 miles (85 km) offshore.[13] While nearly stationary, Hurricane Ella produced waves of 5 to 9 feet (2 to 3 metres) in height, as well as rip currents along the coast.[14] The highest wind gust from the storm over land was 31 mph (50 km/h) at Diamond Shoal Light. The waves reached the dunes along most beaches,[15] causing some minor beach erosion; the depleted sand returned within a few days.[16] Further north, along the coast of Virginia, no large waves were reported, which was considered unusual for how close the hurricane was to the state.[17]

Ultimately, the most significant effect from the hurricane was the significant drop in tourism.[1] The Labor Day Weekend is typically the last significant week of the summer tourist season, and normally, many people vacation along the Outer Banks. Due to the hurricane watch, traffic was light, and many businesses and hotels reported much less business than usual. A forecaster with the National Weather Service said the hurricane watch was put into effect because of "thousands of people streaming in and only one road off the Outer Banks, [and they] couldn't wait until the last minute."[18] The same forecaster noted that an "alert" less than a hurricane watch "would have been used [during Ella].[15]

No significant impact was reported in Canada,[1] as the strongest winds were south and east of the center.[8] Prior to the storm's arrival, the Newfoundland Weather Forecast Office issued a hurricane warning for southeastern Newfoundland.[19] The ferry between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland was disrupted, and boats across the region were sent back to harbor. Rainfall was fairly light, peaking at 2.39 inches (60.8 mm) in southeastern Newfoundland, and sustained winds reached 71 mph (115 km/h) at Cape Race.[7]

Hurricane Ella prompted a scare for engineers secretly working to remedy a structural flaw in the Citigroup Center in New York City, as the high winds could have caused the building to collapse.[20] Ultimately the engineers solved the flaw by welding heavy steel plates over the bolted joints on the support columns at the building's base.

See also

- Other tropical cyclones named Ella

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1950–1979)

- Hurricane Gladys (1975)

References

- Miles B. Lawrence (1978). "Hurricane Ella Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- Frank (1978-08-30). "Tropical Depression Advisory". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- Hebert (1978-08-30). "Tropical Storm Ella Special Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- Miles Lawrence (1978-08-31). "Hurricane Ella Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Pelissier (1978-09-02). "Hurricane Ella Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Pelissier (1978-09-03). "Hurricane Ella Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2010-09-14). "1978-Ella". Retrieved 2010-11-01.

- John Hope (1978-09-05). "Hurricane Ella Advisory 24". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Miles Lawrence (1978-09-05). "Hurricane Ella Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- A.J. Hull (1978-09-01). "Special Request to East North Carolina and Southeast Virginia". Cape Hatteras National Weather Service. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Cape Hatteras National Weather Service (1978-09-01). "Hurricane Ella Local Statement Number 3". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Cape Hatteras National Weather Service (1978-09-02). "Hurricane Ella Local Statement Number 6". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Cape Hatteras National Weather Service (1978-09-02). "Hurricane Ella Local Statement Number 10". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Cape Hatteras National Weather Service (1978-09-02). "Hurricane Ella Local Statement Number 12". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- A. J. Hull (1978-09-07). "Preliminary Report on Hurricane Ella". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Albert R. Hinn (1978-09-07). "Information for Hurricane Ella Survey Report". Wilmington National Weather Service. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Terry Ritter (1978-09-06). "Storm Report, Hurricane Ella". Norfolk National Weather Service. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Coastland Times (1978-09-07). "News Clippings about Hurricane Ella". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Gilbert Clark (1978-09-04). "Hurricane Ella Advisory 22". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Werner, Joel. "The Design Flaw That Almost Wiped Out an NYC Skyscraper". Slate.