Hurricane Carrie

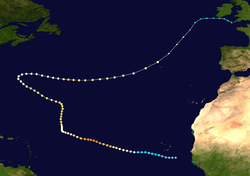

Hurricane Carrie was the strongest tropical cyclone of the 1957 Atlantic hurricane season. The third named storm and second hurricane of the year, Carrie formed from an easterly tropical wave off the western coast of Africa on September 2, a type of tropical cyclogenesis typical of Cape Verde-type hurricanes. Moving to the west, the storm gradually intensified, reaching hurricane strength on September 5. Carrie intensified further, before reaching peak intensity on September 8 as a Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) in the open Atlantic Ocean. The hurricane curved northwards and fluctuated in intensity as it neared Bermuda on September 14. However, Carrie passed well north of the island and turned to the northeast towards Europe. Weakening as it reached higher latitudes, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 23, prior to affecting areas of the British Isles, and subsequently dissipated on September 28.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

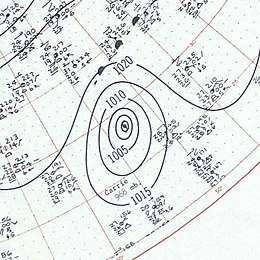

Surface analysis of Hurricane Carrie on September 14 | |

| Formed | September 2, 1957 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 28, 1957 |

| (Extratropical after September 23) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 945 mbar (hPa); 27.91 inHg |

| Fatalities | 83 |

| Areas affected | Bermuda, Azores, British Isles, France |

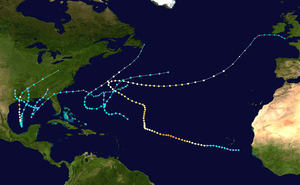

| Part of the 1957 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Due to its distance away from any major land masses, Carrie caused relatively minor damage along its path. On September 16, the hurricane passed well north of Bermuda, causing minimal damage despite its intensity at the time, though hurricane reconnaissance flights in the area were postponed due to damage sustained by one of the aircraft. As it was transitioning to an extratropical cyclone southwest of the Azores, the German ship Pamir encountered the storm and capsized on September 21, resulting in the deaths of 80 crew members on board. As an extratropical storm, Carrie brought strong storm surge and heavy rain to the British Isles, which claimed three lives. The hurricane's long duration and path in open water also helped it attain a number of Atlantic hurricane records.

Meteorological history

In early September, a trough was identified along the western coast of Africa. Moving towards the west as a result of a strong Azores High, the disturbance passed over Cape Verde on September 2. Observations from weather stations evidenced cyclonic rotation in the region. An airplane belonging to Panair do Brasil passed within the vicinity of the vorticity and as a result reported the formation of a tropical storm.[1] In HURDAT—the official database listing all known Atlantic tropical cyclones since 1851—the system was listed to have reached tropical depression intensity at 0600 UTC that day.[2]

The depression continued to steadily intensify as it moved westwards, later reaching the equivalent of a modern-day Category 1 hurricane by 0600 UTC on September 5.[2] On September 6, the ship African Star encountered the hurricane 700 mi (1,100 km) west of Cape Verde. Reported winds of 92 mph (148 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1001 mbar (hPa; 29.56 inHg) confirmed the existence of the tropical cyclone.[1] A Weather Bureau forecaster remarked that the hurricane was in a "blind spot" at the time due to its location outside of shipping lanes and Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions.[3] Throughout the day, the hurricane intensified, reaching major hurricane intensity by 0000 UTC on September 7.[2] Shortly after, a United States Air Force reconnaissance flight headed for Bermuda was diverted to observe the hurricane. The flight reported a well-defined eye measuring 20 mi (32 km) across and a minimum pressure of 945 mbar (hPa; 27.91 inHg), the lowest measured in relation to the hurricane.[1] At the time, Carrie had maximum sustained winds of 135 mph (217 km/h), equivalent to a modern-day Category 4 hurricane. Further strengthening ensued, and the hurricane peaked in intensity on September 8 with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h).[2]

After reaching peak intensity on September 8, Carrie began to gradually weaken due to a decreasing pressure gradient caused by a trough that had cut through the Azores High.[1] By September 11, the hurricane had degenerated into a Category 1 hurricane.[2] A reconnaissance flight reported a minimum pressure of 984 mbar (hPa; 29.06 inHg). At the same time, Carrie began to slowly curve towards the north in response to the trough.[1] The storm later began to slowly reintensify, reattaining major hurricane strength by 1200 UTC on September 13. The restrengthening of the subtropical ridge on September 14 caused the hurricane to quickly curve towards the northwest.[1] National Hurricane Research Project (NHRP) observers described the hurricane as "one of the most perfectly formed hurricanes they had seen."[1] Carrie began to steadily weaken again beginning on September 15.[2] As it passed north of Bermuda the following day, weather radar imagery from the island indicated that the hurricane had an ill-defined structure, with its eye having expanded to 40–70 mi (64–113 km) in diameter.[1] However, as it curved and accelerated eastward in response to a second trough of low pressure,[1] Carrie maintained hurricane intensity up until September 23, when it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The remnant system continued eastwards until it dissipated over Ireland by 1800 UTC on September 28.[2]

Preparations, impact, and records

Preparations and impact

After reports confirmed the existence of a hurricane in the eastern Atlantic, the Weather Bureau warned shipping lanes in the storm's path.[4] Small craft warnings were issued for offshore areas from Block Island, Rhode Island south to Savannah, Georgia on September 7 due to the threat of rough seas.[5] After Carrie stalled on September 11, the Weather Bureau gave Florida a slight chance of being affected by the storm,[6] but the possibilities of the storm affecting the peninsula decreased after the hurricane curved northwards.[7] After the storm was forecast to potentially impact Bermuda, schools were closed in preparation for Carrie, while vessels were warned of the oncoming hurricane.[8] Most planes in Kindley Air Force Base on the island were evacuated, with the remaining planes weighted down by sandbags.[9] After passing Bermuda, the storm was forecast to strike Nova Scotia,[10] but instead Carrie curved towards the northeast.[2]

As the U.S. Air Force was maintaining continuous reconnaissance of the hurricane using converted Boeing B-50 Superfortresses, one of the planes lost an engine and was forced to fly back to West Palm Beach, Florida for repairs. Four other undamaged aircraft were called back to West Palm Beach, including a crippled ship, while two other B-50s were held at Bermuda.[11] Passing well north of the island on September 16,[1] effects of Carrie on Bermuda were minimal, with peak gusts reaching only 35 mph (56 km/h).[12]

The German barque Pamir, en route from Buenos Aires to Hamburg, Germany, encountered the hurricane southwest of the Azores on September 21 while carrying barley cargo.[13] The ship sank due to the effects of Carrie, and 80 people out of the 86 crew members on board the ship perished.[1] The final message received from the Pamir was a distress call and indicated that the ship had lost all of its sails and had been listing at a 45° angle.[14] A search and rescue operation ensued after the loss of the ship was reported, involving the U.S. Air Force and Navy, as well as the British Air Force and Navy. Other ships from Canada and Portugal were also involved in the search.[15] All associated groups were inconclusive in their findings, with no sign of debris left from the ship.[13] However, two lifeboats and a raft were found, but they were empty.[15] As an extratropical storm, Carrie impacted the Azores, though damages, if any, remain unknown. The extratropical remnants of Carrie later struck the British Isles on September 24 and 25, causing strong winds, waves, and severe flooding.[1] Winds from the system were estimated at 50 mph (80 km/h). The strong waves caused extensive property damage and killed three.[16]

Records

Lasting as a hurricane for 20.75 days, Carrie was at the time tied for second in terms of longest-existing Atlantic tropical cyclones, alongside the ninth hurricane of the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season and behind the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane.[17] Due to the hurricane's long duration, the Weather Bureau office in San Juan, Puerto Rico issued 62 advisories on the storm, which was at the time the most ever issued in association with an Atlantic hurricane.[18] Carrie's long duration and distance from any land masses also contributed to its record travel distance of 6,000 mi (9,700 km).[1] Hurricane Faith of 1966 surpassed this record after it traveled 6,850 mi (11,020 km).[19] Hurricane reconnaissance flights throughout Carrie's existence traveled further east than any previous flight due to the storm's location far from any land masses. The initial flight on September 7 covered 3,700 mi (6,000 km) and lasted for nearly 17 hours.[1]

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricane Lorenzo (2019) – Another long-lived major hurricane over the open Atlantic

- Tropical Storm Carrie (1972) – Other storm with the same name

References

- Moore, Paul L. (December 1, 1957). "The Hurricane Season of 1957" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. 85 (12): 401–408. Bibcode:1957MWRv...85..401M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1957)085<0401:THSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Storm Area Is Reported Off Antilles". Miami Sunday News. September 6, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- "Hurricane Warnings Up". The Montreal Gazette. San Juan, Puerto Rico. Associated Press. September 6, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Big Hurricane Is Far Out In Atlantic; Storm Heads North". Gettysburg Times. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 7, 1957. p. 4. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Forecasters Allow Carrie 'Slight Chance' at Florida". The Victoria Advocate. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 11, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Carrie Gains In Intensity". The Victoria Advocate. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 12, 1957. p. 1.

- "Hurricane "Carrie" May Remain At Sea". The Lewiston Daily Sun. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 16, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Hurricane Carrie Hits Bermuda". The Washington Reporter. Hamilton Bermuda. United Press. September 16, 1957. p. 5. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Nova Scotia Expects Carrie to Hit". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Canadian Press. September 18, 1957. p. 6. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Carrie Poses Peril To Bermuda". Sarasota Journal. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 13, 1957. p. 5. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "New Tropical Storm Picks Up Force". Beaver Valley Times. New Orleans, Louisiana. United Press. September 18, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Hope Dwindles for German Sailing". Ellensburg Daily Record. London. Associated Press. September 20, 1957. p. 1. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Presume Sailing Ship With 86 Aboard Lost". Park City Daily News. London. Associated Press. September 20, 1957. p. 5. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "2 Lifeboats, Raft Found In Atlantic". The Windsor Daily Star. London. Associated Press. September 21, 1957. p. 2. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "World Briefs". The Owosso Argus-Press. London. Associated Press. September 25, 1957. p. 21. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- Dorst, Neal; Atlantic Oceanographic Meteorological Laboratory (January 26, 2010). "Subject: E6) Which tropical cyclone lasted the longest?". Tropical Cyclones Records. Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Weeks, Sinclair; Reichelderfer, F.W. (1958). "Annual Summary 1957". Climatological Data – Alabama. Asheville, North Carolina: University of Michigan. 44 (13): 104–105. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Dorst, Neal; Delgado, Sandy (May 20, 2011). Subject: E7) What is the farthest a tropical cyclone has traveled? (Report). Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2013.