Hope (painting)

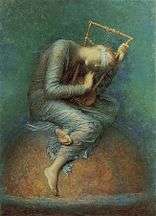

Hope is a Symbolist oil painting by the English painter George Frederic Watts, who completed the first two versions in 1886. Radically different from previous treatments of the subject, it shows a lone blindfolded female figure sitting on a globe, playing a lyre that has only a single string remaining. The background is almost blank, its only visible feature a single star. Watts intentionally used symbolism not traditionally associated with hope to make the painting's meaning ambiguous. While his use of colour in Hope was greatly admired, at the time of its exhibition many critics disliked the painting. Hope proved popular with the Aesthetic Movement, who considered beauty the primary purpose of art and were unconcerned by the ambiguity of its message. Reproductions in platinotype, and later cheap carbon prints, soon began to be sold.

| Hope | |

|---|---|

Second version of Hope, 1886 | |

| Artist | George Frederic Watts |

| Year | 1886, further versions 1886–1895[1] |

| Type | Oil |

| Dimensions | 142.2 cm × 111.8 cm (56.0 in × 44.0 in) |

| Location | Tate Britain |

Although Watts received many offers to buy the painting, he had agreed to donate his most important works to the nation and felt it would be inappropriate not to include Hope. Consequently, later in 1886 Watts and his assistant Cecil Schott painted a second version. On its completion Watts sold the original and donated the copy to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum); thus, this second version is better known than the original. He painted at least two further versions for private sale.

As cheap reproductions of Hope, and from 1908 high-quality prints, began to circulate in large quantities, it became a widely popular image. President Theodore Roosevelt displayed a copy at his Sagamore Hill home in New York; reproductions circulated worldwide; and a 1922 film depicted Watts's creation of the painting and an imagined story behind it. By this time Hope was coming to seem outdated and sentimental, and Watts was rapidly falling out of fashion. In 1938 the Tate Gallery ceased to keep their collection of Watts's works on permanent display.

Despite the decline in Watts's popularity, Hope remained influential. Martin Luther King Jr. based a 1959 sermon, now known as Shattered Dreams, on the theme of the painting, as did Jeremiah Wright in Chicago in 1990. Among the congregation for the latter was the young Barack Obama, who was deeply moved. Obama took "The Audacity of Hope" as the theme of his 2004 Democratic National Convention keynote address, and as the title of his 2006 book; he based his successful 2008 presidential campaign around the theme of "Hope".

Background

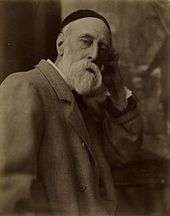

George Frederic Watts was born in London in 1817, the son of a musical instrument manufacturer. His two brothers died in 1823 and his mother in 1826, giving Watts an obsession with death throughout his life. Meanwhile, his father's strict evangelical Christianity led to both a deep knowledge of the Bible and a strong dislike of organised religion.[2] Watts was apprenticed as a sculptor at the age of 10, and six years later was proficient enough as an artist to earn a living as a portrait painter and cricket illustrator.[3] Aged 18 he gained admission to the Royal Academy schools, although he disliked their methods and his attendance was intermittent.[4] In 1837 Watts was commissioned by Greek shipping magnate Alexander Constantine Ionides to copy a portrait of his father by Samuel Lane; Ionides preferred Watts's version to the original and immediately commissioned two more paintings from him, allowing Watts to devote himself full-time to painting.[5]

In 1843 he travelled to Italy where he remained for four years.[6] On his return to London he suffered from depression and painted a number of notably gloomy works.[7] His skills were widely celebrated, and in 1856 he decided to devote himself to portrait painting.[8] His portraits were extremely highly regarded.[8] In 1867 he was elected a Royal Academician, at the time the highest honour available to an artist,[6][upper-alpha 1] although he rapidly became disillusioned with the culture of the Royal Academy.[11] From 1870 onwards he became widely renowned as a painter of allegorical and mythical subjects;[6] by this time, he was one of the most highly regarded artists in the world.[12] In 1881 he added a glass-roofed gallery to his home at Little Holland House, which was open to the public at weekends, further increasing his fame.[13] In 1884 a selection of 50 of his works was shown at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.[13]

Subject

Hope is traditionally considered by Christians as a theological virtue (a virtue associated with the grace of God, rather than with work or self-improvement). Since antiquity artistic representations of the personification depict her as a young woman, typically holding a flower or an anchor.[14][upper-alpha 2]

During Watts's lifetime, European culture had begun to question the concept of hope.[14] A new school of philosophy at the time, based on the thinking of Friedrich Nietzsche, saw hope as a negative attribute that encouraged humanity to expend their energies on futile efforts.[14] The Long Depression of the 1870s wrecked both the economy and confidence of Britain, and Watts felt that the encroaching mechanisation of daily life, and the importance of material prosperity to Britain's increasingly dominant middle class, were making modern life increasingly soulless.[15]

In late 1885 Watts's adopted daughter Blanche Clogstoun had just lost her infant daughter Isabel to illness,[16] and Watts wrote to a friend that "I see nothing but uncertainty, contention, conflict, beliefs unsettled and nothing established in place of them."[17] Watts set out to reimagine the depiction of Hope in a society in which economic decline and environmental deterioration were increasingly leading people to question the notion of progress and the existence of God.[18][19][upper-alpha 3]

Other artists of the period had already begun to experiment with alternative methods of depicting Hope in art. Some, such as the upcoming young painter Evelyn De Morgan, drew on the imagery of Psalm 137 and its description of exiled musicians refusing to play for their captors.[21] Meanwhile, Edward Burne-Jones, a friend of Watts who specialised in painting mythological and allegorical topics, in 1871 completed the cartoon for a planned stained glass window depicting Hope for St Margaret's Church in Hopton-on-Sea.[21][upper-alpha 4] Burne-Jones's design showed Hope upright and defiant in a prison cell, holding a flowering rod.[21]

Watts generally worked on his allegorical paintings on and off over an extended period, but it appears that Hope was completed relatively quickly. He left no notes regarding his creation of the work, but his close friend Emilie Barrington noted that "a beautiful friend of mine", almost certainly Dorothy Dene, modelled for Hope in 1885.[22] (Dorothy Dene, née Ada Alice Pullen, was better known as a model for Frederic Leighton but is known to have also modelled for Watts in this period. Although the facial features of Hope are obscured in Watts's painting, her distinctive jawline and hair are both recognisable.[22]) By the end of 1885 Watts had settled on the design of the painting.[23]

Composition

Hope sitting on a globe, with bandaged eyes playing on a lyre which has all the strings broken but one out of which poor little tinkle she is trying to get all the music possible, listening with all her might to the little sound—do you like the idea?

— George Frederic Watts in a letter to his friend Madeline Wyndham, December 1885[17]

Hope shows its central character alone, with no other human figures visible and without her traditional fellow virtues, Love (also known as Charity) and Faith.[19] She is dressed in classical costume, based on the Elgin Marbles;[19] Nicholas Tromans of Kingston University speculated that her Greek style of clothing was intentionally chosen to evoke the ambivalent nature of hope in Greek mythology over the certainties of Christian tradition.[19] Her pose is based on that of Michelangelo's Night, in an intentionally strained position.[24] She sits on a small, imperfect orange globe with wisps of cloud around its circumference, against an almost blank mottled blue background.[21][25] The figure is illuminated faintly from behind, as if by starlight, and also directly from the front as if the observer is the source of light.[26] Watts's use of light and tone avoids the clear definition of shapes, creating a shimmering and dissolving effect more typically associated with pastel work than with oil painting.[27]

The design bears close similarities to Burne-Jones's Luna (painted in watercolour 1870 and in oils c. 1872–1875), which also shows a female figure in classical drapery on a globe surrounded by clouds.[21] As with many of Watts's works the style of the painting was rooted in the European Symbolist movement, but also drew heavily on the Venetian school of painting.[28] Other works which have been suggested as possible influences on Hope include Burne-Jones's The Wheel of Fortune (c. 1870),[29][upper-alpha 5] Albert Moore's Beads (1875),[29] Dante Gabriel Rossetti's A Sea–Spell (1877),[21] and The Throne of Saturn by Elihu Vedder (1884).[29]

Hope is closely related to Idle Child of Fancy, completed by Watts in 1885, which also shows a personification of one of the traditional virtues (in this case Love) sitting on a cloud-shrouded globe. In traditional depictions of the virtues, Love was shown blindfolded while Hope was not; in Hope and Idle Child Watts reversed this imagery, depicting Love looking straight ahead and Hope as blind.[29] It is believed to be the first time a European artist depicted Hope as blind.[29]

The figure of Hope holds a broken lyre, based on an ancient Athenian wood and tortoiseshell lyre then on display in the British Museum.[29][upper-alpha 6] Although broken musical instruments were a frequently occurring motif in European art, they had never previously been associated with Hope.[29][upper-alpha 7] Hope's lyre has only a single string remaining, on which she attempts to play.[31][upper-alpha 8] She strains to listen to the sound of the single unbroken string, symbolising both persistence and fragility, and the closeness of hope and despair.[24] Watts had recently shown interest in the idea of a continuity between the visual arts and music, and had previously made use of musical instruments as a way to invigorate the subjects of his portraits.[16]

Above the central figure shines a single small star at the very top of the picture, serving as a symbol of further hope beyond that of the central figure herself.[33] The distance of the star from the central figure, and the fact that it is outside her field of vision even were she not blindfolded, suggests an ambiguity. It provides an uplifting message to the viewer that things are not as bad for the central character as she believes, and introduces a further element of pathos in that she is unaware of hope existing elsewhere.[22]

Reception

Hope's dress is of a dark aërial hue, and her figure is revealed to us by a wan light from the front and the paler light of stars in the sky beyone. This exquisite illumination fuses, so to say, the colours, substance and even the forms and contours of the whole, and suggests a vague, dreamlike magic, the charm of which assorts with the subject, and, as in all great art, imparts grace to the expression of the theme.

Deary! a young woman tying herself into a knot and trying to perform the chair-trick. She is balanced on a pantomime Dutch cheese, which is floating in stage muslin of uncertain age and colour. The girl would be none the worse for a warm bath.

Although the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition was traditionally the most prestigious venue for English artists to display their new material, Watts chose to exhibit Hope at the smaller Grosvenor Gallery. In 1882 the Grosvenor Gallery had staged a retrospective exhibition of Watts's work and he felt an attachment to the venue.[25] Also, at this time the Grosvenor Gallery was generally more receptive than the Royal Academy to experimentation.[25] Hope was given the prime spot in the exhibition, in the centre of the gallery's longest wall.[25]

Watts's use of colour was an immediate success with critics; even those who otherwise disliked the piece were impressed by Watts's skilful use of colour, tone and harmony. Its subject and Watts's technique immediately drew criticism from the press.[35] The Times described it as "one of the most interesting of [Watts's] recent pictures" but observed that while "in point of colour Mr. Watts has seldom given us anything more lovely and delicate ... and there is great beauty in the drawing, though it must be owned that the angles are too many and too marked".[36] The Portfolio praised Watts's Repentance of Cain but thought Hope "a poetic but somewhat inferior composition".[37] Theodore Child of The Fortnightly Review dismissed Hope as "a ghastly and apocalyptic allegory",[38][upper-alpha 9] while the highly regarded critic Claude Phillips considered it "an exquisite concept, insufficiently realised by a failed execution".[39][upper-alpha 10]

Despite its initial rejection by critics, Hope proved immediately popular with many in the then-influential Aesthetic Movement, who considered beauty the primary purpose of art.[35][40] Watts, who saw art as a medium for moral messages, strongly disliked the doctrine of "art for art's sake",[25] but the followers of Aestheticism greatly admired Watts's use of colour and symbolism in Hope.[41] Soon after its exhibition poems based on the image began to be published, and platinotype reproductions—at the time the photographic process best able to capture subtle variations in tone—became popular.[42] The first platinotype reproductions of Hope were produced by Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, son of Watts's close friend Julia Margaret Cameron.[42]

Religious interpretations

Because Hope was a work that was impossible to read using the traditional interpretation of symbolism in painting, Watts intentionally left its meaning ambiguous,[43] and the bleaker interpretations were almost immediately challenged by Christian thinkers following its exhibition.[42] Scottish theologian P. T. Forsyth felt that Hope was a companion to Watts's 1885 Mammon in depicting false gods and the perils awaiting those who attempted to follow them in the absence of faith.[44] Forsyth wrote that the image conveyed the absence of faith, illustrated that a loss of faith placed too great a burden on hope alone, and that the message of the painting was that in the godless world created by technology, Hope has intentionally blinded herself and listens only to that music she can make on her own.[44] Forsyth's interpretation, that the central figure is not herself a personification of hope but a representation of humanity too horrified at the world it has created to look at it, instead deliberately blinding itself and living in hope, became popular with other theologians.[44]

Watts's supporters claimed that the image of Hope had near-miraculous redemptive powers.[45] In his 1908 work Sermons in Art by the Great Masters, Stoke Newington Presbyterian minister James Burns wrote of a woman who had been walking to the Thames with the intention of suicide, but had passed the image of Hope in a shop window and been so inspired by the sight of it that rather than attempting suicide she instead emigrated to Australia.[46] In 1918 Watts's biographer Henry William Shrewsbury wrote of "a poor girl, character-broken and heart-broken, wandering about the streets of London with a growing feeling that nothing remained but to destroy herself" seeing a photograph of Hope, using the last of her money to buy the photograph, until "looking at it every day, the message sank into her soul, and she fought her way back to a life of purity and honour".[47] When music hall star Marie Lloyd died in 1922 after a life beset with alcohol, illness and depression, it was noted that among her possessions was a print of Hope; one reporter observed that among her other possessions, it looked "like a good deed in a naughty world".[48]

Watts himself was ambivalent when questioned about the religious significance of the image, saying that "I made Hope blind so expecting nothing",[44] although after his death his widow Mary Seton Watts wrote that the message of the painting was that "Faith must be the companion of Hope. Faith is the substance, the assurance of things hoped for, because it is the evidence of things not seen."[44] Malcolm Warner, curator of the Yale Center for British Art, interpreted the work differently, writing in 1996 that "the quiet sound of the lyre's single string is all that is left of the full music of religious faith; those who still listen are blindfolded in the sense that, even if real reasons for Hope exist, they cannot see them; Hope remains a virtue, but in the age of scientific materialism a weak and ambiguous one".[24]

In 1900, shortly before his death, Watts again painted the character in Faith, Hope and Charity (now in the Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin). This shows her smiling and with her lyre restrung, working with Love to persuade a blood-stained Faith to sheath her sword; Tromans writes that "the message would appear to be that if Faith is going to resume her importance for humanity ... it will have to be in a role deferential to the more constant Love and Hope."[49]

Second version

By the time Hope was exhibited, Watts had already committed himself to donate his most significant works to the nation, and although he received multiple offers for the painting he thought it inappropriate not to include Hope in this donation, in light of the fact that it was already being considered one of his most important pictures.[42] In mid-1886 Watts and his assistant Cecil Schott painted a duplicate of the piece, with the intention that this duplicate be donated to the nation allowing him to sell the original.[42] Although the composition of this second painting is identical, it is radically different in feel.[50] The central figure is smaller in relation to the globe, and the colours darker and less sumptuous, giving it an intentionally gloomier feel than the original.[51]

In late 1886 this second version was one of nine paintings donated to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) in the first instalment of Watts's gift to the nation.[51] Meanwhile, the original was briefly displayed in Nottingham before being sold to the steam tractor entrepreneur Joseph Ruston in 1887.[51] Its whereabouts was long unknown until in 1986 it was auctioned at Sotheby's for £869,000 (about £2,600,000 in 2020 terms[52]), 100 years after its first exhibition.[53]

On their donation to the South Kensington Museum, the nine works donated by Watts were hung on the staircase leading to the library,[upper-alpha 11] but Hope proved a popular loan to other institutions as a symbol of current British art. At the Royal Jubilee Exhibition of 1887 in Manchester, an entire wall was dedicated to the works of Watts. Hope, only recently completed but already the most famous of Watts's works, was placed at the centre of this display.[55] It was then exhibited at the 1888 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition and the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, before being moved to Munich for display at the Glaspalast.[56] In 1897 it was one of the 17 Watts works transferred to the newly created National Gallery of British Art (commonly known as the Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain);[57] at the time, Watts was so highly regarded that an entire room of the new museum was dedicated to his works.[58] The Tate Gallery considered Hope one of the highlights of their collection and did not continue the South Kensington Museum's practice of lending the piece to overseas exhibitions.[59]

Other painted versions

Needing funds to pay for his new house and studio in Compton, Surrey, now the Watts Gallery, Watts produced further copies of Hope for private sale. A small 66 by 50.8 cm (26.0 by 20.0 in) version was sold to a private collector in Manchester at some point between 1886 and 1890,[51] and was exhibited at the Free Picture Exhibition in Canning Town (an annual event organised by Samuel Barnett and Henrietta Barnett in an effort to bring beauty into the lives of the poor[60]) in 1897.[61] It is now in the Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town.[62] Another version, in which Watts included a rainbow surrounding the central figure to reduce the bleakness of the image, was bought by Richard Budgett, a widower whose wife had been a great admirer of Watts,[51] and remained in the possession of the family until 1997.[63] Watts gave his initial oil sketch to Frederic Leighton; it has been in the collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool since 1923.[63] Watts is thought to have painted at least one further version, but its location is unknown.[51]

Legacy

Although Victorian painting styles went out of fashion soon after Watts's death, Hope has remained extremely influential. Mark Bills, curator of the Watts Gallery, described Hope as "the most famous and influential" of all Watts's paintings and "a jewel of the late nineteenth-century Symbolist movement".[64] In 1889 socialist agitator John Burns visited Samuel and Henrietta Barnett in Whitechapel, and saw a photograph of Hope among their possessions. After Henrietta explained its significance to him, efforts were made by the coalition of workers' groups which were to become the Labour Party to recruit Watts. Although determined to stay outside of politics, Watts wrote in support of striking busmen in 1891, and in 1895 donated a chalk reproduction of Hope to the Missions to Seamen in Poplar in support of London dock workers.[65] (This is believed to be the red chalk version of Hope now in the Watts Gallery.[65]) The passivity of Watts's depiction of Hope drew criticism from some within the socialist movement, who saw her as embodying an unwillingness to commit to action.[66] The prominent art critic Charles Lewis Hind also loathed this passivity, writing in 1902 that "It is not a work that the robust admire, but the solitary and the sad find comfort in it. It reflects the pretty, pitiable, forlorn hope of those who are cursed with a low vitality, and poor physical health".[26]

Henry Cameron's platinotype reproductions of the first version of Hope had circulated since the painting's exhibition, but were slow to produce and expensive to buy. From the early 1890s photographer Frederick Hollyer produced large numbers of cheap platinotype reproductions of the second version,[49] particularly after Hollyer formalised his business relationship with Watts in 1896.[67] Hollyer sold the reproductions both via printsellers around the country and directly via catalogue, and the print proved extremely popular.[54]

Artistic influence

.jpg)

In 1895 Frederic Leighton based his painting Flaming June, which also depicted Dorothy Dene,[68] on the composition of Watts's Hope.[51] Flaming June kept the central figure's pose, but showing her as relaxed and sleeping.[51] Dene had worked closely with Leighton since the 1880s, and was left the then huge sum of £5000 (about £600,000 in 2020 terms[52]) in Leighton's will when he died the following year.[69][upper-alpha 12] By this time, Hope was becoming an icon of English popular culture, propelled by the wide distribution of reproductions;[54] in 1898, a year after the opening of the Tate Gallery, its director noted that Hope was one of the two most popular works in their collection among students.[59][upper-alpha 13]

As the 20th century began, the increasingly influential Modernist movement drew its inspiration from Paul Cézanne and had little regard for 19th-century British painting.[70] Watts drew particular dislike from English critics, and Hope came to be seen as a passing fad, emblematic of the excessive sentimentality and poor taste of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[55][71] By 1904 author E. Nesbit used Hope as a symbol of poor taste in her short story The Flying Lodger,[upper-alpha 14] describing it as "a blind girl sitting on an orange", a description which would later be popularised by Agatha Christie in her 1942 novel Five Little Pigs (also known as Murder in Retrospect).[55][upper-alpha 15]

Although Watts's work was seen as outdated and sentimental by the English Modernist movement, his experimentation with Symbolism and Expressionism drew respect from the European Modernists, notably the young Pablo Picasso, who echoed Hope's intentionally distorted features and broad sweeps of blue in The Old Guitarist (1903–1904).[74][75] Despite Watts's fading reputation at home, by the time of his death in 1904 Hope had become a globally recognised image. Reproductions circulated in cultures as diverse as Japan, Australia and Poland,[56] and Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States, displayed a reproduction in his Summer White House at Sagamore Hill.[56] By 1916, Hope was well known enough in the United States that the stage directions for Angelina Weld Grimké's Rachel explicitly use the addition of a copy of Hope to the set to suggest improvements to the home over the passage of time.[76][upper-alpha 16]

Some were beginning to see it as embodying sentimentality and bad taste, but Hope continued to remain popular with the English public. In 1905 The Strand Magazine noted that it was the most popular picture in the Tate Gallery, and remarked that "there are few print-sellers who fail to exhibit it in their windows."[77] After Watts's death the Autotype Company purchased from Mary Seton Watts the rights to make carbon print copies of Hope, making reproductions of the image affordable for poorer households,[71] and in 1908 engraver Emery Walker began to sell full-colour photogravure prints of Hope, the first publicly available high-quality colour reproductions of the image.[78]

In 1922 the American film Hope, directed by Legaren à Hiller and starring Mary Astor and Ralph Faulkner, was based on the imagined origins of the painting. In it Joan, a fisherman's wife, is treated poorly by the rest of her village in her husband's absence, and has only the hope of his return to cling to. His ship returns but bursts into flames, before he is washed up safe and well on shore. The story is interspersed with scenes of Watts explaining the story to a model, and with stills of the painting.[79][80] By the time the film was released, the fad for prints of Hope was long over, to the extent that references to it had become verbal shorthand for authors and artists wanting to indicate that a scene was set in the 1900s–1910s.[81] Watts's reputation continued to fade as artistic tastes changed, and in 1938 the Tate Gallery removed their collection of Watts's works from permanent display.[82]

Later influence

Despite the steep decline in Watts's popularity, Hope continued to hold a place in popular culture,[16] and there remained those who considered it a major work. When the Tate Gallery held an exhibition of its Watts holdings in 1954, trade unionist and left-wing M.P. Percy Collick urged "Labour stalwarts" to attend the exhibition, supposedly privately recounting that he had recently met a Viennese Jewish woman who during "the terrors of the Nazi War" had drawn "renewed faith and hope" from her photographic copy.[66][upper-alpha 17] Meanwhile, an influential 1959 sermon by Martin Luther King Jr., now known as Shattered Dreams, took Hope as a symbol of frustrated ambition and the knowledge that few people live to see their wishes fulfilled, arguing that "shattered dreams are a hallmark of our mortal life", and against retreating into either apathetic cynicism, a fatalistic belief in God's will or escapist fantasy in response to failure.[83]

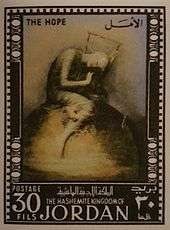

Myths continued to grow about supposed beliefs in the redemptive powers of Hope, and in the 1970s a rumour began spread that after Israel defeated Egypt in the Six-Day War, the Egyptian government issued copies of it to its troops.[75] There is no evidence this took place, and the story is likely to stem from the fact that in early 1974, shortly after the Yom Kippur War between Israel and Egypt, the image of Hope appeared on Jordanian postage stamps.[48][upper-alpha 18] Likewise, it is regularly claimed that Nelson Mandela kept a print of Hope in his cell on Robben Island, a claim for which there is no evidence.[48]

In 1990 Barack Obama, at the time a student at Harvard Law School, attended a sermon at the Trinity United Church of Christ preached by Jeremiah Wright.[86][87][upper-alpha 19] Taking the Books of Samuel as a starting point, Wright explained that he had studied Watts's Hope in the 1950s, and had rediscovered the painting when Dr Frederick G. Sampson delivered a lecture on it in the late 1980s (Sampson described it as "a study in contradictions"), before discussing the image's significance in the modern world.[86][87]

The painting depicts a harpist, a woman who at first glance appears to be sitting atop a great mountain. Until you take a closer look and see that the woman is bruised and bloodied, dressed in tattered rags, the harp reduced to a single frayed string. Your eye is then drawn down to the scene below, down to the valley below, where everywhere are the ravages of famine, the drumbeat of war, a world groaning under strife and deprivation. It is this world, a world where cruise ships throw away more food in a day than most residents of Port-au-Prince see in a year, where white folks' greed runs a world in need, apartheid in one hemisphere, apathy in another hemisphere ... That's the world! On which hope sits! [...] And yet consider once again the painting before us. Hope! Like Hannah, that harpist is looking upwards, a few faint tones floating upwards towards the heavens. She dares to hope ... she has the audacity ... to make music ... and praise God ... on the one string ... she has left!

Wright's sermon left a great impression on Obama, who recounted Wright's sermon in detail in his memoir Dreams from My Father.[91] Soon after Dreams From My Father was published he went into politics, entering the Illinois Senate. In 2004 he was chosen to deliver the keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention. In Obama's 2006 memoir The Audacity of Hope, he recollects that on being chosen to deliver this speech, he pondered the topics on which he had previously campaigned, and on major issues then affecting the nation, before thinking about the variety of people he had met while campaigning, all endeavouring in different ways to improve their own lives and to serve their country.[92]

It wasn't just the struggles of these men and women that had moved me. Rather, it was their determination, their self-reliance, a relentless optimism in the face of hardship. It brought to mind a phrase that my pastor, Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr.' had once used in a sermon. The audacity of hope ... It was that audacity, I thought, that joined us as one people. It was that pervasive spirit of hope that tied my own family's story to the larger American story, and my own story to those of the voters I sought to represent.

— Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope, 2006[92]

Obama's speech, on the theme of "The Audacity of Hope", was extremely well received. Obama was elected to the U.S. Senate later that year, and two years later published a second volume of memoirs, also titled The Audacity of Hope. Obama continued to campaign on the theme of "hope", and in his 2008 presidential campaign his staff requested that artist Shepard Fairey amend the wording of an independently produced poster he had created, combining an image of Obama and the word progress, to instead read hope.[93] The resulting poster came to be viewed as the iconic image of Obama's ultimately successful election campaign.[94] In light of Obama's well-known interest in Watts's painting, and amid concerns over a perceived dislike of the British, in the last days of Gordon Brown's government historian and Labour Party activist Tristram Hunt proposed that Hope be transferred to the White House.[53][95] According to an unverified report in the Daily Mail, the offer was made but rejected by Obama, who wished to distance himself from Jeremiah Wright following controversial remarks made by Wright.[53]

Hope remains Watts's best known work,[16] and formed the theme of the opening ceremony of the 1998 Winter Paralympics in Nagano.[96] In recognition of its continued significance, a major redevelopment of the Watts Gallery completed in 2011 was named the Hope Appeal.[97][98]

Notes

- In Watts's time, honours such as knighthoods were only bestowed on presidents of major institutions, not on even the most well-respected artists.[9] In 1885 serious consideration was given to raising Watts to the peerage; had this happened, he would have been the first artist thus honoured.[10] In the same year, he refused the offer of a baronetcy.[6]

- The anchor in some Christian depictions of Hope is a reference to Hebrews 6:19, "Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and stedfast, and which entereth into that within the veil."[14]

- G. K. Chesterton, in his 1904 biography of Watts, attempted to describe the attitudes of artists who felt themselves surrounded by ugliness, in a culture in which what had previously been political and religious certainties had been thrown into turmoil by scientific and social developments. 'The attitude of that age [...] was an attitude of devouring and concentrated interest in things which were, by their own system, impossible or unknowable. Men were, in the main, agnostics: they said, "We do not know"; but not one of them ever ventured to say, "We do not care." In most eras of revolt and question, the sceptics reap something from their scepticism: if a man were a believer in the eighteenth century, there was Heaven; if he were an unbeliever, there was the Hell-Fire Club. But these men restrained themselves more than hermits for a hope that was more than half hopeless, and sacrificed hope itself for a liberty which they would not enjoy; they were rebels without deliverance and saints without reward. There may have been and there was something arid and over-pompous about them: a newer and gayer philosophy may be passing before us and changing many things for the better; but we shall not easily see any nobler race of men. And its supreme and acute difference from most periods of scepticism, from the later Renaissance, from the Restoration and from the hedonism of our own time was this, that when the creeds crumbled and the gods seemed to break up and vanish, it did not fall back, as we do, on things yet more solid and definite, upon art and wine and high finance and industrial efficiency and vices. It fell in love with abstractions and became enamoured of great and desolate words.'[20]

- Burne-Jones created multiple versions of his Hope design throughout the rest of his life. Other than the Hopton window itself, significant versions of the work include an 1877 watercolour now in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, and an 1896 oil painting now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[21]

- The best known version of The Wheel of Fortune is the 1883 version now in the Musée d'Orsay, which bears little resemblance to Hope. At the time Hope was painted Watts owned an early sketch, now in the Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, in which the figure of Fortune is blindfold against a blue background.[29]

- British Museum item number 1816,0610.501; the lyre was sold to the museum by Lord Elgin in 1816. As of 2016 the lyre remains on public display.[30]

- Since antiquity the unstrung lyre had been considered a symbol of separated lovers and unrequited love.[31] The use of the unstrung lyre as symbolic of separated lovers dates back at least to the early Roman Empire. Petronius's Satyricon, written in the first century A.D., mentions a visit to an art gallery by the narrator Encolpius in which he sees a painting of Apollo holding an unstrung lyre in tribute to his recently-deceased lover Hyacinth.[31]

- Playing musical instruments using only a single string had been popularised in the early 19th century by Niccolò Paganini. It is not certain whether Watts was intentionally aiming to evoke a sense of ostentatious virtuosity in Hope.[32]

- In the same review, Child described Watts's The Soul's Prison as a "sinister spider's web of red and green slime".[38]

- "C'est une pensée exquise, insuffisamment mise en évidence par une exécution défaillante."

- Not all staff at the South Kensington Museum welcomed Watts's gift; an internal memo of the time commented that "it is very difficult to deal with a man like this who has a very great idea of his own genius and in whom a great many of the public also believe".[54]

- As well as the £5000 Leighton bequeathed directly to Dene, he left a further £5000 to support her siblings, three of whom had also on occasion modelled for him.[69]

- The only painting in the Tate collection considered as popular was Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Beata Beatrix.[59]

- "All the walls were white plaster, the furniture was white deal—what there was of it, which was precious little. There were no carpets—only white matting. And there was not a single ornament in a single room! There was a clock on the dining-room mantel-piece, but that could not be counted as an ornament because of the useful side of its character. There were only about six pictures—all of a brownish colour. One was the blind girl sitting on an orange with a broken fiddle. It is called Hope."[72]

- "The walls were distempered an ascetic pale grey, and various reproductions hung upon them. Danté meeting Beatrice on a bridge, and that picture once described by a child as a 'blind girl sitting on an orange and called, I don't know why, Hope'."[73]

- Time: October sixteenth, four years later; seven o'clock in the morning. Scene: The same room. There have been very evident improvements made. The room is not so bare; it is cosier [...] Hanging against the side of the run that faces front is Watts's "Hope".[76]

- The truth of this story is unconfirmed. It does not appear in any of Collick's writings, and first appeared in a 1975 biography of Watts by Wilfred Blunt based on private conversation between Blunt and Collick.[66]

- The use of Hope on Jordanian stamps was not a response to military defeat, but had been planned well before the war took place;[48] it was one of a series of stamps issued by Jordan in 1974 depicting noteworthy European paintings.[84] Although a token force of Jordanian troops participated in the Yom Kippur War, their presence was symbolic and there was an agreement between Israel and Jordan that their forces would not engage with each other.[85]

- Obama's Dreams From My Father places him as attending this sermon in 1988 before entering Harvard Law School, but Wright's own records show that the sermon was delivered in 1990.[88] In mid-1990 Obama worked as an associate attorney at the Chicago firm of Hopkins & Sutter so was in the city at the time.[89] Obama admits in the preface to Dreams From My Father that the chronology of events in the book is unreliable.[90]

- Wright's own text of the sermon does not match that recorded by Obama in all aspects. In particular, Obama misremembered Wright's phrase "The Audacity to Hope" as "The Audacity of Hope".[88]

References

- Tromans 2011, pp. 65–68.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 20.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, pp. 21–22.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 22.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 23.

- Warner 1996, p. 238.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 29.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 33.

- Robinson 2007, p. 135.

- Tromans 2011, p. 69.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 40.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. xi.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 42.

- Tromans 2011, p. 11.

- Warner 1996, p. 30.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 220.

- Letter from Watts to Madeline Wyndham, 8 December 1885, now in the Tate Archives, quoted Tromans 2011, p. 70.

- Warner 1996, p. 31.

- Tromans 2011, p. 12.

- Chesterton 1904, p. 12.

- Tromans 2011, p. 13.

- Tromans 2011, p. 16.

- Tromans 2011, p. 17.

- Warner 1996, p. 135.

- Tromans 2011, p. 19.

- Tromans 2011, p. 60.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 222.

- Tromans 2011, p. 39.

- Tromans 2011, p. 14.

- "Lyre". London: The British Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- Tromans 2011, p. 15.

- Tromans 2011, pp. 14–15.

- Tromans 2011, pp. 15–16.

- "Quisby and Barkins at the Grosvenor Gallery". Fun. London: Gilbert Dalziel: 224. 19 May 1886., quoted Tromans 2011, p. 55.

- Tromans 2011, p. 20.

- "The Grosvenor Gallery". The Times (31749). London. 3 May 1886. col A, p. 7.

- "Art Chronicle". The Portfolio. London: 84. April 1886. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- Child, Theodore (June 1886). "Pictures in London and Paris". The Fortnightly Review. London: Chapman and Hall. 45 (39): 789.

- Phillips, Claude (July 1886). "Correspondence d'Angleterre". Gazette des Beaux-Arts (in French). Paris: 76.

- Warner 1996, p. 26.

- Tromans 2011, pp. 20–21.

- Tromans 2011, p. 21.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 223.

- Tromans 2011, p. 34.

- Tromans 2011, pp. 60–61.

- Burns 1908, p. 17.

- Shrewsbury 1918, p. 64.

- Tromans 2011, p. 62.

- Tromans 2011, p. 35.

- Tromans 2011, pp. 21–22.

- Tromans 2011, p. 22.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Tromans 2011, p. 64.

- Tromans 2011, p. 36.

- Tromans 2011, p. 9.

- Tromans 2011, p. 49.

- Bills 2011, p. 9.

- Bills 2011, p. 5.

- Tromans 2011, p. 37.

- Tromans 2011, p. 23.

- Tromans 2011, p. 24.

- Tromans 2011, p. 28.

- Tromans 2011, p. 66.

- Tromans 2011, p. 7.

- Tromans 2011, p. 33.

- Tromans 2011, p. 59.

- Tromans 2011, pp. 35–36.

- Monahan 2016, p. 69.

- Robbins 2016, p. 71.

- Warner 1996, p. 11.

- Tromans 2011, p. 51.

- Nesbit, Edith (2013). Delphi Complete Novels of E. Nesbit. Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-909496-87-3. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- Christie 1942, p. 86.

- Tromans 2011, p. 40.

- Barlow, Paul (2004). "Where there's life there's". Tate Etc. Archived from the original on 11 September 2004. Retrieved 12 March 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimké 1920, p. 31.

- "Which Are the Most Popular Pictures? II.—In the Tate Gallery". The Strand Magazine. London: George Newnes. January 1905., reproduced Tromans 2011, p. 37

- Tromans 2011, pp. 51–52.

- Hope (1922) on YouTube

- Tromans 2011, pp. 54–55.

- Tromans 2011, p. 52.

- Bills 2011, p. 7.

- King, Martin Luther (1959). "Shattered Dreams". Atlanta, GA: The King Center. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "Jordan Stamp 1974". Jordan Post. Amman. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Ofer Aderet (12 September 2013). "Jordan and Israel cooperated during Yom Kippur War, documents reveal". Haaretz.

- Obama 1995, p. 292.

- Tromans 2011, p. 63.

- Tromans 2011, p. 74.

- Aguilar, Louis (11 July 1990). "Survey: Law firms slow to add minority partners". Chicago Tribune. p. 1 (Business). Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- Obama 1995, p. xvii.

- Obama 1995, pp. 292–293.

- Obama 2006, p. 356.

- Ben Arnon, "How the Obama "Hope" Poster Reached a Tipping Point and Became a Cultural Phenomenon: An Interview With the Artist Shepard Fairey", The Huffington Post, 13 October 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "Copyright battle over Obama image". BBC. 5 February 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Hunt, Tristram (14 January 2009). "The perfect gift to soothe Obama's British suspicions". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "Paralympics Nagano '98". Bonn: International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Tromans 2011, p. 8.

- Staley & Underwood 2006, p. 70.

Bibliography

- Bills, Mark (2011). Painting for the Nation: G. F. Watts at the Tate. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 978-0-9561022-5-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bills, Mark; Bryant, Barbara (2008). G. F. Watts: Victorian Visionary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15294-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burns, James (1908). Sermons in Art by the Great Masters. London: Duckworth.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chesterton, G. K. (1904). G. F. Watts. London: Duckworth. OCLC 26773336.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christie, Agatha (1942). Murder in Retrospect (1985 ed.). New York, NY: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-35038-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimké, Angelina W. (1920). Rachel: A Play in Three Acts. Boston: The Cornhill Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monahan, Patrick (2016). "Flaming June: The Accidental Icon". In Blake, Catherine (ed.). Flaming June: The Making of an Icon. London: Leighton House Museum. pp. 62–70. ISBN 978-0-9931059-1-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Obama, Barack (1995). Dreams From My Father (2008 UK ed.). Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84767-094-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Obama, Barack (2006). The Audacity of Hope (2007 UK ed.). Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84767-083-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robbins, Daniel (2016). "Leighton's Late Models". In Blake, Catherine (ed.). Flaming June: The Making of an Icon. London: Leighton House Museum. pp. 70–75. ISBN 978-0-9931059-1-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Leonard (2007). William Etty: The Life and Art. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2531-0. OCLC 751047871.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shrewsbury, Henry William (1918). The Visions of an Artist: Studies in G. F. Watts, R. A., O. M.; with Verse Interpretations. London: Charles H. Kelly.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Staley, Allen; Underwood, Hilary (2006). Painting the Cosmos: Landscapes by G. F. Watts. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 0-9548230-5-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tromans, Nicholas (2011). Hope: The Life and Times of a Victorian Icon. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 978-0-9561022-7-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warner, Malcolm (1996). The Victorians: British Painting 1837–1901. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6342-9. OCLC 59600277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Catalogue entry from the Tate Gallery

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)